Dead-ball era

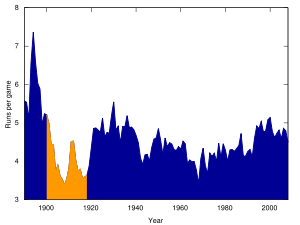

In baseball, the dead-ball era was the period between around 1900 (though some date it to the beginning of baseball) and the emergence of Babe Ruth as a power hitter in 1919. That year, Ruth hit a then-league record 29 home runs, a spectacular feat at that time.

This era was characterized by low-scoring games and a lack of home runs. The lowest league run average in history was in 1908, when teams averaged only a combined 3.4 runs per game.

Baseball during the dead-ball era

During the dead-ball era, baseball was much more of a strategy-driven game, using a style of play now known as small ball or inside baseball. It relied much more on stolen bases and hit-and-run types of plays than on home runs.[1] These strategies emphasized speed, perhaps by necessity.

Teams played in spacious ball parks that limited hitting for power, and, compared to modern baseballs, the ball used then was "dead" both by design and from overuse. Low-power hits like the Baltimore Chop, developed in the 1890s by the Baltimore Orioles, were used to get on base.[2] Once on base, a runner would often steal or be bunted over to second base and move to third base or score on a hit-and-run play. In no other era have teams stolen as many bases as in the dead-ball era.

On 13 occasions between 1900 and 1920, the league leader in home runs had fewer than 10 home runs for the season, as opposed to just 4 where the league leaders had 20 or more homers. Meanwhile, there were 20 instances where the league leader in triples had 20 or more.

Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder Owen "Chief" Wilson set a record of 36 triples in 1912, a little-known record that is likely one of baseball's unbreakable records, as is that of the 309 career triples of Sam Crawford set during this time.[3]

Despite their speed, teams struggled to score during the dead-ball era. Major league cumulative batting averages ranged between .239 and .279 in the National League and between .239 and .283 in the American League. The lack of power in the game also meant lower slugging averages and on-base percentages, as pitchers could challenge hitters more without the threat of the long ball. The nadir of the dead-ball era was around 1907 and 1908, with a league-wide batting average of .239, slugging average of .306, and ERA under 2.40. In the latter year, the Chicago White Sox hit three home runs for the entire season, yet they finished 88–64, just a couple of games from winning the pennant.[4]

"This should prove that leather is mightier than wood".[5]

—White Sox Manager Fielder Jones, after his 1906 "Hitless Wonders" won the World Series with a .230 club batting average

Some players and fans complained about the low-scoring games, and baseball sought to remedy the situation. In 1909, Ben Shibe invented the cork-centered ball, which the Reach Company—official ball supplier to the American League (AL)—began marketing.[6] Spalding, who supplied the National League (NL), followed with its own cork-center ball.

The change in the ball dramatically affected play in both leagues.[6] In 1910, the American League batting average was .243; in 1911, it rose to .273. The National League saw a jump in the league batting average from .256 in 1910 to .272 in 1912. 1911 happened to be the best season of Ty Cobb’s career; Cobb batted .420 with 248 hits. Joe Jackson hit .408 in 1911, and the next year Cobb batted .410. These were the only .400 averages between 1902 and 1919.

In 1913, however, pitchers started to regain control, helped by a serendipitous invention by minor league pitcher Russ Ford. Ford accidentally scuffed a baseball against a concrete wall, and after he threw it, noticed the pitch quickly dived as it reached the batter. The emery pitch was born. Soon pitchers not only had the dominating spitball; they had another pitch in their arsenal to control the batter, aided by the fact that the same ball was used throughout the game and almost never replaced. As play continued, the ball became increasingly scuffed. This made it harder to hit as it moved more during the pitch, and more difficult to see as it became dirtier. By 1914 run scoring was essentially back to the pre-1911 years and remained so until 1919.[7]

Such a lack of power in the game led to one of the more unusual player nicknames in history. Frank Baker, one of the best players of the dead-ball era, earned the nickname of "Home Run" Baker merely for hitting two home runs in the 1911 World Series. Although Baker led the American League in home runs four times (1911–1914), his highest home run season was 1913, when he hit 12 home runs,[8] and he finished with 96 home runs for his career.

The best homerun hitter of the dead-ball era was Philadelphia Phillies outfielder "Cactus" Gavvy Cravath. Cravath led the National League in home runs six times, with a high total of 24 for the pennant-winning Phillies in 1915 and seasons of 19 home runs each in 1913 and 1914. Cravath, however, was aided by batting in the Baker Bowl, a notoriously hitter-friendly park with only a short 280-foot (85 m) distance from the plate to the right field wall.

Factors that contributed to the dead-ball era

The following factors contributed to the dramatic decline in runs scored during the dead-ball era:

The foul strike rule

The foul strike rule was a major rule change that, in just a few years, sent baseball from a high-scoring game to a game where scoring any runs was a struggle. Prior to this rule, foul balls did not count as strikes. Thus, a batter could foul off a countless number of pitches with no strikes counted against him—except for bunt attempts. This gave the batter an enormous advantage. In 1901, the National League adopted the foul strike rule, and the American League followed suit in 1903.[9]

The ball itself

Before 1921, it was common for a baseball to be in play for over 100 pitches. Players used the same ball until it started to unravel. Early baseball leagues were very cost-conscious, so fans had to throw back balls that had been hit into the stands. The longer the ball was in play, the softer it became—and hitting a heavily used, softer ball for distance is much more difficult than hitting a new, harder one. The ball itself was softer to begin with, probably making home runs less likely.

The spitball

The ball was also hard to hit because pitchers could manipulate it before a pitch. For example, the spitball pitch was permitted in baseball until 1921. Pitchers often marked the ball, scuffed it, spat on it—anything they could to influence the ball's motion. This made the ball "dance" and curve much more than it does now, making it more difficult to hit. Tobacco juice was often added to the ball as well, which discolored it. This made the ball difficult to see, especially since baseball parks did not have lights until the late 1930s. This made both hitting and fielding more difficult.

Ballpark dimensions

Many ballparks were large by modern standards, such as the West Side Grounds of the Chicago Cubs, which was 560 feet to the center field fence, and the Huntington Avenue Grounds of the Boston Red Sox, which was 635 feet to the center field fence. The dimensions of Braves Field prompted Ty Cobb to say that no one would ever hit the ball out of it.

The end of the dead-ball era

The dead-ball era ended suddenly. By 1921, offenses were scoring 40% more runs and hitting four times as many home runs as they had in 1918. The abruptness of this change causes widespread debate among baseball historians, with no consensus on its cause.[10][11] Six popular theories have been advanced:

- Changes in the ball: This theory claims that owners replaced the ball with a newer, livelier ball (sometimes referred to as the "jackrabbit" ball), presumably with the intention of boosting offense and, by extension, ticket sales. The theory has been rebutted by Major League Baseball. The yarn used to wrap the core of the ball was changed prior to the 1920 season, although testing by the United States Bureau of Standards found no difference in the physical properties of the two different types of balls. The so-called "livelier" ball was actually introduced in 1911, when the league began using a cork-centered ball, as opposed to rubber.[12] This led to an increase in hitting. The Major League runs per game jumped from 3.83 to 4.51. Major League batting average increased from .249 to .266, with two hitters, Ty Cobb and Shoeless Joe Jackson, hitting over .400 (.420 and .408, respectively). Most notably, the number of total home runs in 1911 went to 514, up from 361 the previous season.[13] Frank Schulte became the first player of the 20th century to reach twenty home runs in a season.

- Outlawing illegal pitches: Pitches now considered illegal, per MLB Rule 8.02(b),[14] were outlawed. This included the shine ball, emery ball, and spitball (a very effective pitch throughout the dead-ball era). This theory states that without such effective pitches in the pitcher's arsenal, batters gained an advantage. When the spitball was outlawed in 1920, MLB recognized seventeen pitchers who had nearly built their careers specializing in the spitball. They were permitted to continue using it for the rest of their careers.[15]

- More baseballs per game: The fatal beaning of Ray Chapman during the 1920 season led to a rule that the baseball must be replaced every time that it got dirty. With a clean ball in play at all times, players no longer had to contend with a ball that "traveled through the air erratically, tended to soften in the later innings, and as it came over the plate, was very hard to see."[16]

- Game-winning home runs: In 1920, Major League Baseball adopted writer Fred Lieb's proposal that a game-winning home run with men on base count as a home run, even if its run is not needed to win the game. Owners tried unsuccessfully to eliminate the intentional walk. They succeeded only in changing the rules to require that the catcher be within the catcher's box when the pitcher throws‚ and that everything that happened in a protested game was added to the game record. (From 1910 to 1919‚ records in protested games were excluded.)

- Babe Ruth: One theory is that the prolific success of Babe Ruth at hitting home runs led players around the league to forsake their old methods of hitting (described above) and adopt a "free-swinging" style designed to hit the ball hard and with an uppercut stroke, with the intention of hitting more home runs. Critics of this theory claim that it doesn't account for the improvement in batting averages from 1918 to 1921, over which time the league average improved from .254 to .291.

- Ballpark dimensions: This theory contends that offensive success came from changes in the dimensions of the ballparks. Accurate estimates of ballpark sizes of the era can be difficult to find, however, so there is disagreement over whether the dimensions changed at all, let alone whether the change led to improved offense. A 1920 season rule change stated that balls hit over the fence in fair territory but landing foul were fair, and hence home runs rather than foul balls. This rule change greatly pleased hitters for both New York City teams, whose many "hooking" home runs were called foul in the Polo Grounds.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Daniel Okrent, Harris Lewine, David Nemec (2000) The Ultimate Baseball Book, Houghton Mifflin Books, ISBN 0-618-05668-8 , p.33

- ↑ Burt Solomon (2000) Where They Ain't: The Fabled Life And Untimely Death Of The Original Baltimore Orioles, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0-684-85917-3 Excerpt

- ↑ Year-by-Year League Leaders & Records, Baseball-Reference.com

- ↑ League Index Season to Season League Statistical Totals, Baseball-Reference.com

- ↑ The Love of Baseball. Paul Adomites, Robert Cassidy, Bruce Herman, Dan Schlossberg, and Saul Wisnia, 2007 ISBN 978-1-4127-1131-9

- 1 2 Rawlings Sporting Goods Company (July 1963). Evolution of the Ball. Baseball Digest. Books.Google.com. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ↑ Timothy A. Johnson (2004) Baseball and the Music of Charles Ives: A Proving Ground, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-4999-2 Excerpt pg. 28

- ↑ http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/b/bakerfr01.shtml

- ↑ Baseball Reference Bullpen Foul strike rule, Baseball-Reference.com

- ↑ Baseball: A History of America's Game. Benjamin Rader, 2002.

- ↑ Koppett's Concise History of Major League Baseball. Leonard Koppett, 1998.

- ↑ James, Bill (2003). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract ([2003 ed.]. ed.). New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-2722-3.

- ↑ "http://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/bat.shtml". External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "Official Baseball Rules 2015 edition" (PDF). Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ↑ "http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Spitball#Grandfathered_Spitballers". External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Baseball: An Illustrated History. Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, 1994.