Diego Rivera

| Diego Rivera | |

|---|---|

Diego Rivera with a xoloitzcuintle, photo taken at the Casa Azul | |

| Born |

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez December 8, 1886 Guanajuato, Mexico |

| Died |

November 24, 1957 (aged 70) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Education | San Carlos Academy |

| Known for | Painting, murals |

| Notable work | Man, Controller of the Universe |

| Movement | Mexican Mural Movement |

| Spouse(s) |

Angelina Beloff (1909) Guadalupe Marín (1922–1929) Frida Kahlo, (1929–1939 and 1940–1954; her death), Emma Hurtado |

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez, known as Diego Rivera (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈdjeɣo riˈβeɾa]; December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was a prominent Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the Mexican Mural Movement in Mexican art. Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted murals among others in Mexico City, Chapingo, Cuernavaca, San Francisco, Detroit, and New York City. In 1931, a retrospective exhibition of his works was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Rivera had a volatile marriage with fellow Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.

Personal life

Rivera was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, to a well-to-do family, the son of María del Pilar Barrientos and Diego Rivera Acosta.[1] Diego had a twin brother named Carlos, who died two years after they were born.[2] Rivera was said to have Converso ancestry (having ancestors who were forced to convert from Judaism to Catholicism).[3] Rivera wrote in 1935: "My Jewishness is the dominant element in my life."[4] Rivera began drawing at the age of three, a year after his twin brother's death. He had been caught drawing on the walls. His parents, rather than punishing him, installed chalkboards and canvas on the walls. As an adult, he married Angelina Beloff in 1911, and she gave birth to a son, Diego (1916–1918). Maria Vorobieff-Stebelska gave birth to a daughter named Marika in 1918 or 1919 when Rivera was married to Angelina (according to House on the Bridge: Ten Turbulent Years with Diego Rivera and Angelina's memoirs called Memorias). He married his second wife, Guadalupe Marín, in June 1922, with whom he had two daughters: Ruth and Guadalupe. He was still married when he met art student Frida Kahlo. They married on August 21, 1929 when he was 42 and she was 22. Their mutual infidelities and his violent temper led to divorce in 1939, but they remarried December 8, 1940 in San Francisco. Rivera later married Emma Hurtado, his agent since 1946, on July 29, 1955, one year after Kahlo's death.

Rivera was an atheist. His mural Dreams of a Sunday in the Alameda depicted Ignacio Ramírez holding a sign which read, "God does not exist". This work caused a furor, but Rivera refused to remove the inscription. The painting was not shown for nine years – until Rivera agreed to remove the inscription. He stated: "To affirm 'God does not exist', I do not have to hide behind Don Ignacio Ramírez; I am an atheist and I consider religions to be a form of collective neurosis."[5]

From the age of ten, Rivera studied art at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City. He was sponsored to continue study in Europe by Teodoro A. Dehesa Méndez, the governor of the State of Veracruz. After arrival in Europe in 1907, Rivera initially went to study with Eduardo Chicharro in Madrid, Spain, and from there went to Paris, France, to live and work with the great gathering of artists in Montparnasse, especially at La Ruche, where his friend Amedeo Modigliani painted his portrait in 1914.[6] His circle of close friends, which included Ilya Ehrenburg, Chaim Soutine, Amedeo Modigliani and Modigliani's wife Jeanne Hébuterne, Max Jacob, gallery owner Léopold Zborowski, and Moise Kisling, was captured for posterity by Marie Vorobieff-Stebelska (Marevna) in her painting "Homage to Friends from Montparnasse" (1962).[7]

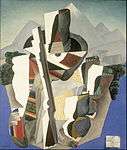

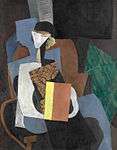

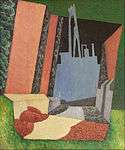

In those years, Paris was witnessing the beginning of Cubism in paintings by such eminent painters as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Juan Gris. From 1913 to 1917, Rivera enthusiastically embraced this new school of art. Around 1917, inspired by Paul Cézanne's paintings, Rivera shifted toward Post-Impressionism with simple forms and large patches of vivid colors. His paintings began to attract attention, and he was able to display them at several exhibitions.

Rivera died on November 24, 1957.[8]

Career in Mexico

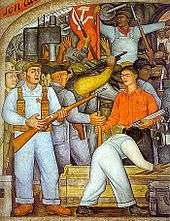

In 1920, urged by Alberto J. Pani, the Mexican ambassador to France, Rivera left France and traveled through Italy studying its art, including Renaissance frescoes. After José Vasconcelos became Minister of Education, Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921 to become involved in the government sponsored Mexican mural program planned by Vasconcelos.[9] See also Mexican muralism. The program included such Mexican artists as José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Rufino Tamayo, and the French artist Jean Charlot. In January 1922,[10] he painted – experimentally in encaustic – his first significant mural Creation[11] in the Bolívar Auditorium of the National Preparatory School in Mexico City while guarding himself with a pistol against right-wing students.

In the autumn of 1922, Rivera participated in the founding of the Revolutionary Union of Technical Workers, Painters and Sculptors, and later that year he joined the Mexican Communist Party[12] (including its Central Committee). His murals, subsequently painted in fresco only, dealt with Mexican society and reflected the country's 1910 Revolution. Rivera developed his own native style based on large, simplified figures and bold colors with an Aztec influence clearly present in murals at the Secretariat of Public Education in Mexico City[13] begun in September 1922, intended to consist of one hundred and twenty-four frescoes, and finished in 1928.[10]

His art, in a fashion similar to the steles of the Maya, tells stories. The mural En el Arsenal (In the Arsenal)[14] shows on the right-hand side Tina Modotti holding an ammunition belt and facing Julio Antonio Mella, in a light hat, and Vittorio Vidali behind in a black hat. However, the En el Arsenal detail shown does not include the right-hand side described nor any of the three individuals mentioned; instead it shows the left-hand side with Frida Kahlo handing out munitions. Leon Trotsky lived with Rivera and Kahlo for several months while exiled in Mexico.[15] Some of Rivera's most famous murals are featured at the National School of Agriculture at Chapingo near Texcoco (1925–27), in the Cortés Palace in Cuernavaca (1929–30), and the National Palace in Mexico City (1929–30, 1935).[16][17][18]

Later years

In the autumn of 1927, Rivera arrived in Moscow, accepting an invitation to take part in the celebration of the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. The following year, while still in Russia, he met the visiting Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who would soon become Rivera's friend and patron, as well as the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art.[19] Rivera was commissioned to paint a mural for the Red Army Club in Moscow, but in 1928 he was ordered out by the authorities because of involvement in anti-Soviet politics, and he returned to Mexico. In 1929, Rivera was expelled from the Mexican Communist Party. His 1928 mural In the Arsenal was interpreted by some as evidence of Rivera's prior knowledge of the murder of Julio Antonio Mella allegedly by Stalinist assassin Vittorio Vidali. After divorcing Guadalupe (Lupe) Marin, Rivera married Frida Kahlo in August 1929. Also in 1929, the first English-language book on Rivera, American journalist Ernestine Evans's The Frescoes of Diego Rivera, was published in New York City. In December, Rivera accepted a commission to paint murals in the Palace of Cortés in Cuernavaca from the American Ambassador to Mexico.[20]

In September 1930, Rivera accepted an invitation from architect Timothy L. Pflueger to paint for him in San Francisco. After arriving in November accompanied by Kahlo, Rivera painted a mural for the City Club of the San Francisco Stock Exchange for US$2,500[21] and a fresco for the California School of Fine Art, later relocated to what is now the Diego Rivera Gallery at the San Francisco Art Institute.[20] Kahlo and Rivera worked and lived at the studio of Ralph Stackpole, who had suggested Rivera to Pflueger. Rivera met Helen Wills Moody, a famous tennis player, who modeled for his City Club mural.[21] In November 1931, Rivera had a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City; Kahlo was present.[22] Between 1932 and 1933, he completed a famous series of twenty-seven fresco panels entitled Detroit Industry on the walls of an inner court at the Detroit Institute of Arts. During the McCarthyism of the 1950s, a large sign was placed in the courtyard defending the artistic merit of the murals while attacking his politics as "detestable."[19]

His mural Man at the Crossroads, begun in 1933 for the Rockefeller Center in New York City, was removed after a furor erupted in the press over a portrait of Vladimir Lenin it contained. When Diego refused to remove Lenin from the painting, Diego was ordered to leave. One of Diego's assistants managed to take a few pictures of the work so Diego was able to later recreate it. The American poet Archibald MacLeish wrote six "irony-laden" poems about the mural.[23] The New Yorker magazine published E. B. White's poem "I paint what I see: A ballad of artistic integrity".[24] As a result of the negative publicity, a further commission was canceled to paint a mural for an exhibition at the Chicago World's Fair. Rivera issued a statement that with the money left over from the commission of the mural at Rockefeller Center (he was paid in full though the mural was supposedly destroyed. Rumors have floated that the mural was actually covered over rather than brought down and destroyed.), he would repaint the same mural over and over wherever he was asked until the money ran out.

In December 1933, Rivera returned to Mexico, and he repainted Man at the Crossroads in 1934 in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. This surviving version was called Man, Controller of the Universe. On June 5, 1940, invited again by Pflueger, Rivera returned for the last time to the United States to paint a ten-panel mural for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. Pan American Unity was completed November 29, 1940. As he was painting, Rivera was on display in front of Exposition attendees. He received US$1,000 per month and US$1,000 for travel expenses.[21]

The mural includes representations of two of Pflueger's architectural works as well as portraits of Kahlo, woodcarver Dudley C. Carter, and actress Paulette Goddard, who is depicted holding Rivera's hand as they plant a white tree together.[21] Rivera's assistants on the mural included the pioneer African-American artist, dancer, and textile designer Thelma Johnson Streat. The mural and its archives reside at City College of San Francisco.[25][26]

Cinematic portrayals

Diego Rivera was portrayed by Rubén Blades in Cradle Will Rock (1999), by Alfred Molina in Frida (2002), and (in a brief appearance) by José Montini in Eisenstein in Guanajuato (2015).

Literary portrayals

Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and Leon Trotsky are principal characters in Barbara Kingsolver's novel, The Lacuna.

Gallery

Paintings

Self-portrait with Broad-Brimmed Hat, 1907, 84.5 × 61.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

Self-portrait with Broad-Brimmed Hat, 1907, 84.5 × 61.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Avila Morning (The Ambles Valley), 1908, 97 × 123 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

Avila Morning (The Ambles Valley), 1908, 97 × 123 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Street in Ávila (Ávila Landscape), 1908, 129 × 141 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

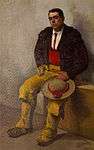

Street in Ávila (Ávila Landscape), 1908, 129 × 141 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte El Picador, 1909, 177 × 113 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

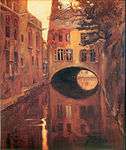

El Picador, 1909, 177 × 113 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo The House on the Bridge, 1909, 147 × 121 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

The House on the Bridge, 1909, 147 × 121 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) After the Storm (The Grounded Ship), 1910, 120.7 × 146.7 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

After the Storm (The Grounded Ship), 1910, 120.7 × 146.7 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte Landscape, 1911. Frida Kahlo Museum.

Landscape, 1911. Frida Kahlo Museum. Portrait of Adolfo Best Maugard, 1913, 227.5 × 161.5 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

Portrait of Adolfo Best Maugard, 1913, 227.5 × 161.5 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte The Sun Breaking through the Mist, 1913, 83.5 × 59 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

The Sun Breaking through the Mist, 1913, 83.5 × 59 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo The Woman at the Well, 1913, 145 × 125 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

The Woman at the Well, 1913, 145 × 125 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte The Alarm Clock, 1914. Frida Kahlo Museum

The Alarm Clock, 1914. Frida Kahlo Museum%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_197.5_x_161.3_cm%2C_The_Arkansas_Arts_Center%2C_Little_Rock%2C_Arkansas.jpg) Two Women (Dos Mujeres, Portrait of Angelina Beloff and Maria Dolores Bastian), 1914, 197.5 x 161.3 cm. Arkansas Arts Center

Two Women (Dos Mujeres, Portrait of Angelina Beloff and Maria Dolores Bastian), 1914, 197.5 x 161.3 cm. Arkansas Arts Center Portrait de Messieurs Kawashima et Foujita, 1914, oil and collage on canvas, 78.5 x 74 cm. Private collection

Portrait de Messieurs Kawashima et Foujita, 1914, oil and collage on canvas, 78.5 x 74 cm. Private collection Young Man with a Fountain Pen, 1914, 79.5 × 63.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

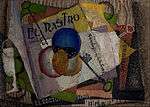

Young Man with a Fountain Pen, 1914, 79.5 × 63.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo El Rastro, 1915, 27.5 × 38.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

El Rastro, 1915, 27.5 × 38.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo Zapata-style Landscape, 1915, 145 × 125 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte

Zapata-style Landscape, 1915, 145 × 125 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte Portrait of Marevna, c.1915, 145.7 x 112.7 cm. Art Institute of Chicago

Portrait of Marevna, c.1915, 145.7 x 112.7 cm. Art Institute of Chicago_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Seated Woman (Women with the Body of a Guitar), 1915-16. Frida Kahlo Museum

Seated Woman (Women with the Body of a Guitar), 1915-16. Frida Kahlo Museum Urban Landscape, 1916. Frida Kahlo Museum

Urban Landscape, 1916. Frida Kahlo Museum%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_67.8_x_53.7cm.jpg) Still Life with Tulips (Naturaleza Muerta con Tulipanes), 1916, oil on canvas, 67.8 x 53.7 cm

Still Life with Tulips (Naturaleza Muerta con Tulipanes), 1916, oil on canvas, 67.8 x 53.7 cm Knife and Fruit in Front of the Window, 1917, 91.8 × 92.4 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

Knife and Fruit in Front of the Window, 1917, 91.8 × 92.4 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo Still Life with Utensils, 1917, 71 × 54 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

Still Life with Utensils, 1917, 71 × 54 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo The Mathematician, 1919, 115.5 × 80.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

The Mathematician, 1919, 115.5 × 80.5 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo

Murals

Mural of exploitation of Mexico by Spanish conquistadors, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (1929–1945)

Mural of exploitation of Mexico by Spanish conquistadors, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City (1929–1945) Mural of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

Mural of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City- Mural of the Aztec market of Tlatelolco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

Mural showing Aztec production of gold, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

Mural showing Aztec production of gold, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City- Mural showing Totonaca celebrations and ceremonies, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

- Detail of Man, Controller of the Universe, fresco at Palacio de Bellas Artes showing Leon Trotsky, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Marx

Detail of Man, Controller of the Universe, fresco at Palacio de Bellas Artes showing Vladimir Lenin

Detail of Man, Controller of the Universe, fresco at Palacio de Bellas Artes showing Vladimir Lenin Mural Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central in Mexico City, featuring Rivera and Frida Kahlo standing by La Calavera Catrina

Mural Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central in Mexico City, featuring Rivera and Frida Kahlo standing by La Calavera Catrina Mural at Palacio de Gobierno, Mexico City

Mural at Palacio de Gobierno, Mexico City

Sculptures and lithographs

.jpg) Zapata (1932)

Zapata (1932) Tlaloc Fountain in Cárcamo de Dolores, Mexico City (1951)

Tlaloc Fountain in Cárcamo de Dolores, Mexico City (1951) 3D mural of Quetzalcóatl in the Exekatlkalli (Casa de los Vientos) in Acapulco, Guerrero (1957)

3D mural of Quetzalcóatl in the Exekatlkalli (Casa de los Vientos) in Acapulco, Guerrero (1957)

See also

- Crystal Cubism

- Anahuacalli Museum

- Cárcamo de Dolores

- Gabriel Bracho, Venezuelan muralist

- Elaine Hamilton-O'Neal

- María Izquierdo

References

- ↑ Diego Rivera Began Drawing As A Toddler

- ↑ online biography Retrieved October 13, 2010

- ↑ "On this day: Diego Rivera dies", The Jewish Chronicle. Thejc.com. Retrieved 20-09-2012

- ↑ "Mexico: Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

- ↑ Philip Stein, Siqueiros: His Life and Works (International Publishers Co, 1994), ISBN 0-7178-0706-1, pp176

- ↑ "Modigliani, Amedeo - 1914 Portrait of Diego Rivera (Museo de Arte, Sao Paolo, Brazil) | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ↑ "M. Marevna, 'Homage to Friends from Montparnasse', 1962, A private collection, Moscow". The State Russian Museum. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera — Biography". artinthepicture.com. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera: Biography". Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- 1 2 "Diego Rivera: Chronology". Yahoo! GeoCities. Archived from the original on 2008-03-08. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera. Creation. / La creación. 1922-3". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera". Fred Buch. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera. From the cycle: Political Vision of the Mexican People (Court of Fiestas): Insurrection aka The Distribution of Arms. / El Arsenal – Frida Kahlo repartiendoarmas". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ Chasteen, John Charles. Born in Blood and Fire, W. W. Norton & Company, 2006, p. 225.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ↑ "Diego Rivera". Answers.com. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ↑ bluffton.edu

- 1 2 Schjeldahl, Peter (28 November 2011). "The Painting on the Wall". The New Yorker. Condé Nast: 84–85. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- 1 2 "The Commission". San Francisco Art Institute. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- 1 2 3 4 Poletti, Therese; Paiva, Tom (2008). Art Deco San Francisco: The Architecture of Timothy Pflueger. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 1-56898-756-0.

- ↑ Gerry Souter (2012). Kahlo. New York: Parkstone International. ISBN 9781780424385. p. 18.

- ↑ "Archibald MacLeish Criticism". Enotes.com. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ↑ "I paint what I see". Art-talks.org. 1933-05-20. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ↑ "The Diego Rivera Mural Project". City college of San Francisco. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ "Pan American Unity Mural". City College of San Francisco. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

Further reading

- Aguilar, Louis. "Detroit was muse to legendary artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo". The Detroit News. April 6, 2011.

- Azuela, Alicia. Diego Rivera en Detroit. Mexico City: UNAM 1985.

- Bloch, Lucienne. "On location with Diego Rivera." Art in America 74 (February 1986, pp. 102-23.

- Craven, David. Diego Rivera as Epic Modernist. New York: G.K. Hall 1997.

- Dickerman, Leah, and Anna Indych-López. Diego Rivera: Murals for the Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art 2011.

- Downs, Linda. Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Murals. Detroit: The Detroit Institute of Arts 1999.

- Evans, Robert [Joseph Freeman]. "Painting and Politics: The Case of Diego Rivera." New Masses (February 1932) 22-25.

- González Mello, Renato. "Manuel Gamio, Diego Rivera and the Politics of Mexican Anthropology." RES 45 (Spring 2004) 161-85.

- Lee, Anthony. Painting on the Left: Rivera, Radical Politics, and San Francisco's Public Murals. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1999.

- Linsley, Robert. "Utopia Will Not be Televised: Rivera at Rockefeller Center." Oxford Art Journal 17, no. 2 (1994) 48-62.

- Moyssén, Xavier, ed. Diego Rivera: Textos de arte. Mexico City: UNAM 1986.

- Rivera, Diego. Arte y política, Raquel Tibol, ed. Mexico City Grijalbo 1979.

- Rivera, Diego and Gladys March. My Life, Life: An Autobiography. New York: Dover Publications 1960.

- Siqueiros, David Alfaro. "Rivera's Counter-Revolutionary Road." New Masses May 29, 1934.

- Rochfort, Desmond. Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros, 2nd edition. San Francisco: Chronicle Books 1998.

- Wolfe, Bertram. The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera. New York: Stein and Day 1963.

- Wolfe, Bertram and Diego Rivera. Portrait of Mexico. New York: Covici, Friede Publishers 1937.

External links

- Creation (1931). From the Collections of the Library of Congress

- Trials of the Hero-Twins (1931) From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Human Sacrifice Before Tohil (1931) From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Diego Rivera at DMOZ

- Diego Rivera discography at Discogs