Dotted note

|

In Western musical notation, a dotted note is a note with a small dot written after it. In modern practice the first dot increases the duration of the basic note by half of its original value. A dotted note is equivalent to writing the basic note tied to a note of half the value; or with more than one dot, tied to notes of progressively halved value.[1] The length of any given note a with n dots is therefore given by the geometric series . More than three dots are highly uncommon but theoretically possible;[2] only quadruple dots have been attested.[3]

A rhythm using longer notes alternating with shorter notes (whether notated with dots or not) is sometimes called a dotted rhythm. Historical examples of music performance styles using dotted rhythm include notes inégales and swing. The precise performance of dotted rhythms can be a complex issue. Even in notation that includes dots, their performed values may be longer than the dot mathematically indicates, a practice known as over-dotting.[4]

Notation

If the note to be dotted is on a space, the dot also goes on the space, while if the note is on a line, the dot goes on the space above (this also goes for notes on ledger lines).[5] However, if a dotted note on a line is part of a chord where a higher note is also on a line, the dot for the lower note is placed in the space below: ![]() [6]

[6]

The dots on dotted notes, which are located to the right of the note, are not to be confused with the dots which indicate staccato articulation, which are located above or below the note as shown in the 3rd and 4th notes of Example 2.

Theoretically, any note value can be dotted, as can rests of any value. If the rest is in its normal position, dots are always placed in third staff space from the bottom.[7]

The use of a dot for augmentation of a note dates back at least to the 10th century, although the exact amount of augmentation is disputed; see Neume.

Dots can be used across barlines, such as in H. C. Robbins Landon's edition of Joseph Haydn's Symphony No. 70 in D major, but most writers today regard this usage as obsolete and recommend using a tie across the barline instead.[8]

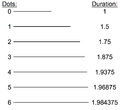

More than one dot may be added; each dot adds half of the duration added by the previous dot, as shown in example 1.

Double dotting

A double-dotted note is a note with two small dots written after it. Its duration is 1¾ times its basic note value.

The double-dotted note is used less frequently than the dotted note. Typically, as in the example below, it is followed by a note whose duration is one-quarter the length of the basic note value, completing the next higher note value.

Before the mid 18th century, double dots were not used. Until then, in some circumstances, single dots could mean double dots.[9]

Example 2 is a fragment of the second movement of Joseph Haydn's string quartet, Op. 74, No. 2, a theme and variations. The first note is double-dotted. Haydn's theme was adapted for piano by an unknown composer; the adapted version can be heard ![]() here (3.7 KB MIDI file).

here (3.7 KB MIDI file).

In a French overture (and sometimes other Baroque music), notes written as dotted notes are often interpreted to mean double-dotted notes,[10] and the following note is commensurately shortened; see Historically informed performance.

Triple dotting

A triple-dotted note is a note with three dots written after it; its duration is 1 7⁄8 times its basic note value. Use of a triple-dotted note value is not common in the Baroque and Classical periods, but quite common in the music of Richard Wagner and Anton Bruckner, especially in their brass parts. See example 3.

An example of the use of double- and triple-dotted notes is the Prelude in G major for piano, Op. 28, No. 3, by Frédéric Chopin. The piece, in common time (4/4), contains running semiquavers (American English: sixteenth note) in the left hand. Several times during the piece Chopin asks for the right hand to play a triple-dotted minim (American English: half note) (lasting 15 semiquavers) simultaneously with the first left-hand semiquaver, then one semiquaver simultaneously with the 16th left-hand semiquaver.

See also

References

- ↑ Gardner Read, Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice 2nd Edition. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, Inc. (1969): 114, Example 8-11; 116, Example 8-18; 117, Example 8-20.

- ↑ Bussler, Ludwig (1890). Elements of Notation and Harmony, p. 14. 2010 edition: ISBN 1-152-45236-3.

- ↑ "Extremes of Conventional Music Notation". indiana.edu.

- ↑ Stephen E. Hefling. "Dotted rhythms". In L. Root, Deane. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- ↑ Glen Rosencrans, Music Notation Primer. New York: Passantino (1979): 29

- ↑ Ted Ross. Teach Yourself The Art of Music Engraving & Processing Hansen Books, Florida.

- ↑ Read (1969): 119; 120, Example 8-28. The author points out the obvious fact "that it is impossible to tie rests."

- ↑ Read (1969): 117–118. "Ranging from Renaissance madrigals to the keyboard works of Johannes Brahms, one often finds such a notation as the one at the left below." (The next page shows an example labeled "older notation" of two measures of music in 4/4 of which the second measure contains, in order: an augmentation dot, a quarter note and a half note.

- ↑ Taylor, Eric (2011). The AB Guide to Music Theory Part I. ABRSM. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-85472-446-5.

- ↑ Adam Carse, 18th Century Symphonies: A Short History of the Symphony in the 18th Century. London: Augener Ltd. (1951): 28. "Contemporary theorists made it clear that the dotted note should be sustained beyond its actual value (the double dot was not then in use), and that the short note or notes should be played as quickly as possible."

External links

![]() Media related to Dotted notes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dotted notes at Wikimedia Commons