Drache-class ironclad

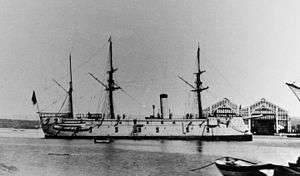

Drache at anchor after her 1867 refit | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders: | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | None |

| Succeeded by: | Kaiser Max class |

| Built: | 1861–62 |

| In commission: | 1862–83 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Scrapped: | 2 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type: | Ironclad armored frigate |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 70.1 m (230 ft 0 in) |

| Beam: | 13.94 m (45 ft 9 in) |

| Draft: | 6.8 m (22 ft 4 in) |

| Installed power: | |

| Propulsion: | 1 Shaft, 1 Steam engine |

| Sail plan: | Barque-rigged |

| Speed: | 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph) |

| Complement: | 346 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | Waterline belt: 115 mm (4.5 in) |

The Drache-class ironclads were a pair of wooden-hulled armored frigates built for the Austro-Hungarian Navy in the 1860s, the first ironclads built for Austria-Hungary. Ordered in response to a pair of Italian ironclads in 1860, Drache and Salamander were laid down in early 1861, launched later that year, and completed in 1862. They participated in the Austrian victory over the Italians in the Battle of Lissa, where Drache destroyed the coastal defense ship Palestro, one of two Italian ships sunk in the action. Both ships were withdrawn from front-line service in 1875. Drache's hull was in poor condition, so she was discarded and eventually broken up in 1883, but Salamander became a harbor guard ship. She was hulked in 1883 and converted into floating storage for naval mines before being scrapped in 1895–1896.

Design

The launch of the French Gloire, the world's first ironclad warship, started a naval arms race between the major European powers. The Austrian Navy began a major ironclad construction program under the direction of Archduke Ferdinand Max, the Marinekommandant (naval commander) and brother of Kaiser Franz Josef I, the emperor of Austria. This program was in response to a similar naval expansion in the recently-united Kingdom of Italy across the Adriatic Sea. Drache and Salamander were ordered in response to the two Formidabile-class ironclads that Italy had bought from France in 1860.[1][2][3] The design work was done by the Austrian Director of Naval Construction, Josef von Romako, who would go on to design all of the Austrian ironclads through to Tegetthoff in the late 1870s.[4] The ships were rated as third-class armored frigates.[5]

Characteristics

The ships of the Drache class were 62.78 meters (206 ft 0 in) long between perpendiculars and had an overall length of 70.1 meters (230 ft 0 in). Their beam measured 13.94 meters (45 ft 9 in) and they had a draft of 6.3 to 6.8 meters (20 ft 8 in to 22 ft 4 in). They displaced 2,824 long tons (2,869 t) at normal load, and 3,110 long tons (3,160 t) at deep load. Their hulls were of wooden construction with iron armor plates riveted over top. The ships had a complement of 346 officers and crewmen.[3][5]

The ships had a horizontal 2-cylinder steam engine that drove their single propeller using steam provided by four coal-fired boilers that exhausted through one funnel. The engine produced a total of 1,842 to 2,060 indicated horsepower (1,374 to 1,536 kW) which gave the ships a speed of 10.5 to 11 knots (19.4 to 20.4 km/h; 12.1 to 12.7 mph). For long-distance travel, the Draches were fitted with three masts and barque rigged. Between 1869 and 1872, both ships had their rigging increased with a larger sail area.[3][5]

The frigates were broadside ironclads, and were armed with ten 48-pounder smoothbore guns and eighteen 24-pounder rifled, muzzle-loading (RML) guns. These guns were mounted in gun ports along the length of the hull. In 1867, these guns were removed, and ten Armstrong RML 7-inch (178 mm) guns and two bronze RML2-inch (51 mm) guns were installed in their place. They were equipped with ram bows. The Drache-class ironclads had a waterline belt of wrought iron that was 115 millimeters (4.5 in) thick.[5]

Ships

| Ship | Builder[5] | Laid down[6] | Launched[5] | Completed[6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMS Drache | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste | 18 February 1861 | 9 September 1861 | November 1862 |

| SMS Salamander | February 1861 | 22 August 1861 | May 1862 |

Service

Two years after the ships entered service, Austria joined Prussia in the Second Schleswig War against Denmark. Drache and Salamander were kept in the Adriatic to defend against a possible Danish attack, which failed to materialize.[7] In 1866, Austria's erstwhile ally Prussia signed an alliance with Italy directed against Austria, beginning the Seven Weeks' War. The Austrian fleet was commanded by Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, who attacked the Italian fleet as it attempted to capture the island of Lissa in the central Adriatic. In the ensuring Battle of Lissa, both ships were heavily engaged, with Drache inflicting fatal damage to the coastal defense ship Palestro, setting her on fire and ultimately destroying her. Drache did not escape unscathed, however, as she was hit by Italian shells numerous times; she lost her main mast, was temporarily set on fire, and her commander was killed.[8] Salamander engaged the leading ships of the Italian line, though neither side inflicted serious damage on the other.[9] Nevertheless, the loss of Palestro and the ironclad Re d'Italia led the demoralized Italian fleet to disengage and retreat to their base at Ancona.[10]

Both ships were modernized twice after the war, receiving new guns in 1867,[11] and again at the end of the decade when their rigging was increased.[5] They saw little use thereafter, however. Badly rotted by 1875, Drache was stricken from the naval register on 13 June that year and eventually broken up for scrap in 1883.[5] Salamander lingered on in service as a guard ship from 1875[12] until 18 March 1883, when she too was stricken from the register and converted into a mine storage hulk. She served in this capacity until 1895 when she was sold for scrap and dismantled over the following year.[5][13]

Footnotes

References

- Dislère, Paul (1877). Die Panzerschiffe der neuesten Zeit. Pola: Druck und Commissionsverlag von Carl Gerold's Sohn. OCLC 25770827.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-938289-58-6.

- Hale, John Richard (1911). Famous Sea Fights From Salamis to Tsu-shima. Boston: Little, Brown, & Company. OCLC 747738440.

- Pawlik, Georg (2003). Des Kaisers Schwimmende Festungen: die Kasemattschiffe Österreich-Ungarns [The Kaiser's Floating Fortresses: The Casemate Ships of Austria-Hungary]. Vienna: Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7083-0045-0.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1111061.