Dry Creek explosives depot

The Dry Creek explosives depot was a secure storage facility near Port Adelaide from 1906 to 1995,[1] serving the construction, mining and quarrying industries of South Australia, as well as the mines of Broken Hill in New South Wales.[2]

Construction

The ten magazines of the Dry Creek explosives depot were built in 1906 at the expenditure of £6,000 or £7,000 at Broad Creek, a tidal distributary channel on the eastern side of the Barker Inlet of the Port River Estuary, which runs in the direction of the suburb of Dry Creek. The Broad Creek site, located on the landward side of intertidal mangroves and supratidal saltmarshes, was chosen as a more isolated location from Port Adelaide, replacing an earlier explosives depot called North Arm Powder Magazine at Magazine Creek at Gillman, south of the North Arm of the Port River.

Horse tram

A narrow gauge tramway with a track gauge of 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) was constructed in 1906. It ran along the magazines and connected the depot via a length of 2 km (1¼ miles) to the landing jetty and on the other side via 800 m (½ mile) to the Dry Creek railway station. Six bespoke wagons were used for the transport of explosives such as dynamite to the magazines - each held 1¼ tons. The wagons were drawn by horses. Previously, explosives had to be transported by road from the North Arm to the magazines, and this both dangerous and expensive.[3] The wagons were donated in 1978 to the Illawarra Light Railway Museum, where they are now exhibited.[4]

Inspection

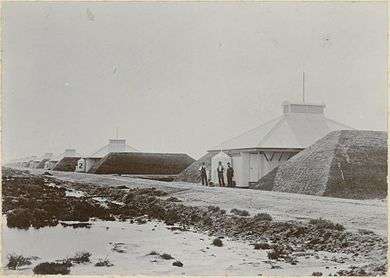

The president of the Marine Board, Arthur Searcy, and four wardens officially inspected the Dry Creek explosives depot on Tuesday, 19 June 1906. They were conveyed to the Broad Creek jetty in the motor launch Warden. The party travelled on one of the horse-drawn wagons to the magazines, which were found in perfect order. Each magazine was capable of storing 40 tons of explosives, but 20 tons were at that time fixed as the maximum quantity to be stored in them. Every precaution was taken to guard against explosion, and printed regulations were exhibited on each of the magazine doors. Mounds had been built between each magazine, so that should one of the magazines explode no injury would result to the others. The party was quite satisfied that the system for the handling and storage of explosives was superior in every respect to the one formerly in use. The magazine reserve, which consisted of about 307 acres, was being improved, by the planting of tamarisk and other trees to provide shadow and explosion breaks.[3]

Operation

Limewash was normally applied to magazines' exterior walls. Care was taken to minimise and isolate the explosives from damp, heat and grit. The magazine structures incorporated insulated walls and were designed to create a naturally and reasonably cooled and ventilated environment. Their ventilation shafts were covered by metal ventilation louvers, coupled with spark arrestors and dust deflectors.

The king tides regularly flooded the estuarine plain. Consequently, the tramline along the mangroves from the magazines to the jetty at Broad Creek was frequently damaged. In July, 1917, the jetty was inundated by the highest tide on record up to that date, 3.6 m above low water, and was washed away. The following August an unusually high tide washed away the gear of the levee workmen, including planks, barrels, barricades and bags of silt, which disappeared without a trace.[2]

Decline

By 1925 explosives were delivered from Deer Park, Victoria less frequently but in larger batches. Therefore, less explosives were delivered via the jetty, the number of daily paid stevedores declined and the turnover was reduced.

By 1934, shipworm and lack of preventive maintenance had materially weakened the wooden structures. From 1934 explosives were railed from Victoria directly to the Dry Creek explosives depot. By 1947 all explosives were delivered this way. In 1950 urgent safety relevant repairs were ordered, but were not conducted until September 1952. Decreasing revenue from the port trade led to lessened maintenance and dredging of the Broad Creek landing. The jetty was last used in February 1970 and demolished about 1976.

As waterborne trade decreased, land transport of explosives was coupled to technological progress in the explosive usage. From early 1978 ammonium nitrate came into fashion as an ingredient of explosives mixtures that could be prepared on-site. This resulted in further safety refinements, and diffusion of responsibility for explosive storage. This eliminated much of the previously needed inspection, sampling and storage.[2]

Closure

The operation of the site ceased in October 1995. Eleven of the historic buildings at Dry Creek, which were built from 1903 to 1907, are still in place and were listed on the Register of State Heritage Items in 1994 as No. 14521. Their condition was generally sound as of the year 2000, but the reinforcement bars of hollow concrete piles, which were installed instead of jarrah piles in the 1960s, are so corroded by the saline soil that the long term stability is under threat.[2][6] Remains of the wharf once used to unload explosives and the narrow gauge railway line are still visible on the seawards side of the salt pans, if Broad Creek is entered by a canoe.[7]

Condition in 2015

|

References

- ↑ "explosives depot • Find • State Library of South Australia". slsa.sa.gov.au.

- 1 2 3 4 Jolly, Bridget (13 April 2000). "High And Dry By The Mangroves? South Australia's Dry Creek Explosives Magazines" (PDF). University of South Australia. originally published in Garnaut, Christin, Ed.; Hamnett, Stephen, Ed. (2000). "High And Dry By The Mangroves? South Australia's Dry Creek Explosives Magazines". Fifth Australian Urban History Planning History Conference. Adelaide: University of South Australia: 222–232. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- 1 2 The Dry Creek Explosives Depot. An official visit. The Advertiser, 20 June 1906.

- ↑ "Explosive Horse Drawn Wagons". Rolling Stock. Illawarra Light Railway Museum Society, ilrms.com.au. 2006. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ Bridget Jolly: A Significant Site: the Former Dry Creek Explosives Reserve. In: Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia, No. 29, 2001, pp. 70–84.

- ↑ Chapter 15: Public Service Facilities. In: Metro Report 1962.

- ↑ Peter Carter: Notes on the Torrens Island and Environs map.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dry Creek explosives magazines. |

Coordinates: 34°49′42″S 138°34′48″E / 34.828347°S 138.579980°E