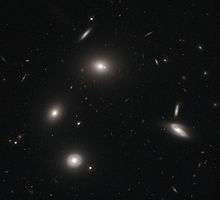

Elliptical galaxy

An elliptical galaxy is a type of galaxy having an approximately ellipsoidal shape and a smooth, nearly featureless brightness profile. Unlike flat spiral galaxies with organization and structure, they are more three-dimensional, without much structure, and their stars are in somewhat random orbits around the center. They are one of the three main classes of galaxy originally described by Edwin Hubble in his 1936 work The Realm of the Nebulae,[1] along with spiral and lenticular galaxies. Elliptical galaxies range in shape from nearly spherical to highly flat and in size from tens of millions to over one hundred trillion stars. Originally Edwin Hubble hypothesized that elliptical galaxies evolved into spiral galaxies, which was later discovered to be false.[2] Stars found inside of elliptical galaxies are much older than stars found in spiral galaxies.[2]

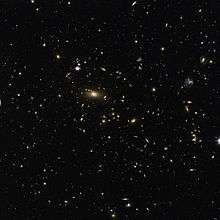

Most elliptical galaxies are composed of older, low-mass stars, with a sparse interstellar medium and minimal star formation activity, and they tend to be surrounded by large numbers of globular clusters. Elliptical galaxies are believed to make up approximately 10–15% of galaxies in the Virgo Supercluster, and they are not the dominant type of galaxy in the universe overall.[3] They are preferentially found close to the centers of galaxy clusters.[4] Elliptical galaxies are (together with lenticular galaxies) also called "early-type" galaxies (ETG), due to their location in the Hubble sequence, and are found to be less common in the early Universe.

General characteristics

Elliptical galaxies are characterized by several properties that make them distinct from other classes of galaxy. They are spherical or ovoid masses of stars, starved of star-making gases. The smallest known elliptical galaxy is about one-tenth the size of the Milky Way. The motion of stars in elliptical galaxies is predominantly radial, unlike the disks of spiral galaxies, which are dominated by rotation. Furthermore, there is very little interstellar matter (neither gas nor dust), which results in low rates of star formation, few open star clusters, and few young stars; rather elliptical galaxies are dominated by old stellar populations, giving them red colors. Large elliptical galaxies typically have an extensive system of globular clusters.[5]

The dynamical properties of elliptical galaxies and the bulges of disk galaxies are similar, [6] suggesting that they are formed by the same physical processes, although this remains controversial. The luminosity profiles of both elliptical galaxies and bulges are well fit by Sersic's law.

Elliptical galaxies are preferentially found in galaxy clusters and in compact groups of galaxies.

Star formation

The traditional portrait of elliptical galaxies paints them as galaxies where star formation finished after an initial burst at high-redshift, leaving them to shine with only their aging stars. Elliptical galaxies typically appear yellow-red, which is in contrast to the distinct blue tinge of most spiral galaxies. In spirals, this blue color emanates largely from the young, hot stars in their spiral arms. Very little star formation is thought to occur in elliptical galaxies, because of their lack of gas compared to spiral or irregular galaxies. However, in recent years, evidence has shown that a reasonable proportion (~25%) of these galaxies have residual gas reservoirs[7] and low level star-formation.[8] Researchers with the Herschel Space Observatory have speculated that the central black holes in elliptical galaxies keep the gas from cooling enough for star formation.[9]

Sizes and shapes

Elliptical galaxies vary greatly in both size and mass, from as little as a tenth of a kiloparsec to over 100 kiloparsecs, and from 107 to nearly 1013 solar masses. This range is much broader for this galaxy type than for any other. The smallest, the dwarf elliptical galaxies, may be no larger than a typical globular cluster, but contain a considerable amount of dark matter not present in clusters. Most of these small galaxies may not be related to other ellipticals.

The Hubble classification of elliptical galaxies contains an integer that describes how elongated the galaxy image is. The classification is determined by the ratio of the major (a) to the minor (b) axes of the galaxy's isophotes:

Thus for a spherical galaxy with a equal to b, the number is 0, and the Hubble type is E0. The limit is about E7, which is believed to be due to a bending instability that causes flatter galaxies to puff up. The most common shape is close to E3. Hubble recognized that his shape classification depends both on the intrinsic shape of the galaxy, as well as the angle with which the galaxy is observed. Hence, some galaxies with Hubble type E0 are actually elongated.

There are two physical types of ellipticals; the "boxy" giant ellipticals, whose shapes result from random motion which is greater in some directions than in others (anisotropic random motion), and the "disky" normal and low luminosity ellipticals, which have nearly isotropic random velocities but are flattened due to rotation.

Dwarf elliptical galaxies have properties that are intermediate between those of regular elliptical galaxies and globular clusters. Dwarf spheroidal galaxies appear to be a distinct class: their properties are more similar to those of irregulars and late spiral-type galaxies.

At the large end of the elliptical spectrum, there is further division, beyond Hubble classification. Beyond gE giant ellipticals, lies D-galaxies and cD-galaxies. These are similar to their smaller brethren, but more diffuse, with larger haloes. Some even appear more akin to lenticular galaxies.

Evolution

It is widely accepted that the main driving force for the evolution of elliptical galaxies is mergers of smaller galaxies. Many galaxies in the universe are gravitationally bound to other galaxies, which means that they will never escape the pull of the other galaxy. If the galaxies are of similar size, the resultant galaxy will appear similar to neither of the two galaxies merging,[12] but will instead be an elliptical galaxy.[13]

Every massive elliptical galaxy would contain a supermassive black hole at its center.[14] The mass of the black hole is tightly correlated with the mass of the galaxy, via the M–sigma relation. It is believed that black holes may play an important role in limiting the growth of elliptical galaxies in the early universe by inhibiting star formation.

Such major galactic mergers are thought to have been common at early times, but may occur less frequently today. Minor galactic mergers involve two galaxies of very different masses, and are not limited to giant ellipticals. For example, our own Milky Way galaxy is known to be consuming a couple of small galaxies right now. The Milky Way galaxy is also, depending upon an unknown tangential component, on a collision course in 4–5 billion years with the Andromeda Galaxy. It has been theorized that an elliptical galaxy will result from a merger of the two spirals.[15]

Examples

- M32

- M49

- M59

- M60 (NGC 4649)

- M87 (NGC 4486)

- M89

- M105 (NGC 3379)

- IC 1101, one of the largest galaxies in the observable universe.

- Maffei 1, the closest giant elliptical galaxy.

- Centaurus A (NGC 5128), a radio galaxy, elliptical/lenticular disputed.

See also

- Firehose instability

- Galaxy color–magnitude diagram

- Galaxy morphological classification

- Hubble sequence

- Lenticular galaxy

- M–sigma relation

- Osipkov–Merritt model

- Sersic profile

Further reading

- Mo, Houjun; van den Bosch, Frank; White, Simon (June 2010), Galaxy Formation and Evolution (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521857932

References

- ↑ Hubble, E.P. (1936). The realm of the nebulae (PDF). Mrs. Hepsa Ely Silliman Memorial Lectures, 25. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300025002. OCLC 611263346. Archived from the original on 2012-09-29.(pp. 124–151)

- ↑ Loveday, J. (February 1996). "The APM Bright Galaxy Catalogue.". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 278 (4): 1025–1048. arXiv:astro-ph/9603040

. Bibcode:1996MNRAS.278.1025L. doi:10.1093/mnras/278.4.1025.

. Bibcode:1996MNRAS.278.1025L. doi:10.1093/mnras/278.4.1025. - ↑ Dressler, A. (March 1980). "Galaxy morphology in rich clusters - Implications for the formation and evolution of galaxies.". The Astrophysical Journal. 236: 351–365. Bibcode:1980ApJ...236..351D. doi:10.1086/157753.

- ↑ Binney, J.; Merrifield, M. (1998). Galactic Astronomy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02565-0. OCLC 39108765.

- ↑ Merritt, D. (February 1999). "Elliptical galaxy dynamics". The Astronomical Journal. 756 (756): 129–168. arXiv:astro-ph/9810371

. Bibcode:1999PASP..111..129M. doi:10.1086/316307.

. Bibcode:1999PASP..111..129M. doi:10.1086/316307. - ↑ Young, L. M.; et al. (June 2011). "The Atlas3D project -- IV: the molecular gas content of early-type galaxies". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 414 (2): 940–967. arXiv:1102.4633

. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.414..940Y. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18561.x.

. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.414..940Y. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18561.x. - ↑ Crocker, A. F.; et al. (January 2011). "Molecular gas and star formation in early-type galaxies". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 410 (2): 1197–1222. arXiv:1007.4147

. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.410.1197C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17537.x.

. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.410.1197C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17537.x. - ↑ "Red And Dead Galaxies Have Beating Black Hole 'Hearts', Preventing Star Formation."

- ↑ "Galactic fireflies". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "Elliptical galaxy IC 2006". www.spacetelescope.org. ESA/Hubble. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ↑ Barnes, Joshua E. (1989-03-09). "Evolution of compact groups and the formation of elliptical galaxies". Nature. 338 (6211): 123–126. Bibcode:1989Natur.338..123B. doi:10.1038/338123a0.

- ↑ (Ho 2010, pp. 12,22,23)

- ↑ (Ho 2010, p. 583)

- ↑ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (4 June 2012). "Milky Way Galaxy Doomed: Collision with Andromeda Pending". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA.

- ↑ "The Calm after the Galactic Storm". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elliptical galaxies. |

- Elliptical Galaxies, SEDS Messier pages

- Elliptical Galaxies