Effect of psychoactive drugs on animals

Psychoactive drugs, such as caffeine, amphetamine, mescaline, LSD, marijuana, chloral hydrate, theophylline, IBMX and others, can have strong effects on certain animals. At small concentrations, some psychoactive drugs reduce the feeding rate of insects and molluscs, and at higher doses some can kill them. Spiders build more disordered webs after consuming most drugs than before. It is believed that plants developed caffeine as a chemical defense against insects.

Spiders

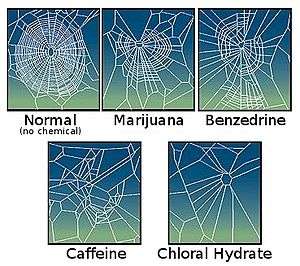

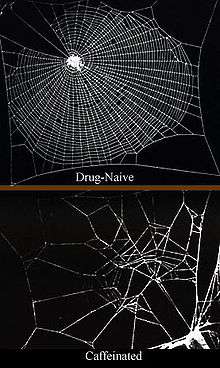

In 1948, Swiss pharmacologist Peter N. Witt started his research on the effect of drugs on spiders. The initial motivation for the study was a request from his colleague, zoologist H. M. Peters, to shift the time when garden spiders build their webs from 2am–5am, which apparently annoyed Peters, to earlier hours. Witt tested spiders with a range of psychoactive drugs, including amphetamine, mescaline, strychnine, LSD, and caffeine, and found that the drugs affect the size and shape of the web rather than the time when it is built. At small doses of caffeine (10 µg/spider), the webs were smaller; the radii were uneven, but the regularity of the circles was unaffected. At higher doses (100 µg/spider), the shape changed more, and the web design became irregular. All the drugs tested reduced web regularity except for small doses (0.1–0.3 µg) of LSD, which increased web regularity.[2]

The drugs were administered by dissolving them in sugar water, and a drop of solution was touched to the spider's mouth. In some later studies, spiders were fed with drugged flies.[3] For qualitative studies, a well-defined volume of solution was administered through a fine syringe. The webs were photographed for the same spider before and after drugging.[2]

Witt's research was discontinued, but it became reinvigorated in 1984 after a paper by J.A. Nathanson in the journal Science,[4] which is discussed below. In 1995, a NASA research group repeated Witt's experiments on the effect of caffeine, benzedrine, marijuana and chloral hydrate on European garden spiders. NASA's results were qualitatively similar to those of Witt, but the novelty was that the pattern of the spider web was quantitatively analyzed with modern statistical tools, and proposed as a sensitive method of drug detection.[1][5]

Other arthropods and molluscs

In 1984, Nathanson reported an effect of methylxanthines on larvae of the tobacco hornworm. He administered solutions of finely powdered tea leaves or coffee beans to the larvae and observed, at concentrations between 0.3 and 10% for coffee and 0.1 to 3% for tea, inhibition of feeding, associated with hyperactivity and tremor. At higher concentrations, larvae were killed within 24 hours. He repeated the experiments with purified caffeine and concluded that the drug was responsible for the effect, and the concentration differences between coffee beans and tea leaves originated from 2–3 times higher caffeine content in the latter. Similar action was observed for IBMX on mosquito larvae, mealworm larvae, butterfly larvae and milkweed bug nymphs, that is, inhibition of feeding and death at higher doses. Flour beetles were unaffected by IBMX up to 3% concentrations, but long-term experiments revealed suppression of reproductive activity.[4]

Further, Nathanson fed tobacco hornworm larvae with leaves sprayed with such psychoactive drugs as caffeine, formamidine pesticide didemethylchlordimeform (DDCDM), IBMX or theophylline. He observed a similar effect, namely inhibition of feeding followed by death. Nathanson concluded that caffeine and related methylxanthines could be natural pesticides developed by plants as protection against worms: Caffeine is found in many plant species, with high levels in seedlings that are still developing foliage, but are lacking mechanical protection;[6] caffeine paralyzes and kills certain insects feeding upon the plant.[4] High caffeine levels have also been found in the soil surrounding coffee bean seedlings. It is therefore understood that caffeine has a natural function, both as a natural pesticide and as an inhibitor of seed germination of other nearby coffee seedlings, thus giving it a better chance of survival.[7]

Coffee borer beetles seem to be unaffected by caffeine, in that their feeding rate did not change when they were given leaves sprayed with caffeine solution. It was concluded that those beetles have adapted to caffeine.[8] This study was further developed by changing the solvent for caffeine. Although aqueous caffeine solutions had indeed no effect on the beetles, oleate emulsions of caffeine did inhibit their feeding, suggesting that even if certain insects have adjusted to some caffeine forms, they can be tricked by changing minor details, such as the drug solvent.[9]

These results and conclusions were confirmed by a similar study on slugs and snails. Cabbage leaves were sprayed with caffeine solutions and fed to Veronicella cubensis slugs and Zonitoides arboreus snails. Cabbage consumption reduced over time, followed by the death of the molluscs.[10] Inhibition of feeding by caffeine was also observed for caterpillars.[11]

Cats

About 70% of domestic cats are especially attracted to, and affected by the plant Nepeta cataria, otherwise known as catnip. Wild cats, including tigers, are also affected, but with unknown percentage. The first reaction of cats is to sniff. Then, they lick and sometimes chew the plant and after that rub against it, with their cheeks and the whole body by rolling over. If cats consume concentrated extract of the plant, they quickly show signs of over-excitement such as violent twitching, profuse salivation and sexual arousal. The reaction is caused by the volatile terpenoids called nepetalactones present in the plant. Although they are mildly toxic and repel insects from the plant, their concentration is too low to poison cats.[12]

Macaque monkeys

Macaque monkeys administered with the antipsychotics haloperidol and olanzapine over a 17–27 month period showed reduced brain volume. These results have not been observed in humans who also take the drug due to the lack of available data.[13][14]

Media

- 2002 British documentary television series Weird Nature episode 6 "Peculiar Potions" documents variety of animals engaging in intoxication or zoopharmacognosy.[15] Much of the material was reused in National Geographic's Worlds Weirdest Happy Hour.[16]

- 2014 documentary Dolphins - Spy in the Pod shows dolphins getting intoxicated on pufferfish.

Further reading

- Siegel, Ronald K. (1989, 2005) Intoxication: The Universal Drive for Mind-Altering Substances

- Samorini, Giorgio (2002) Animals and Psychedelics: The Natural World And The Instinct To Alter Consciousness

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Noever, R., J. Cronise, and R. A. Relwani. 1995. Using spider-web patterns to determine toxicity. NASA Tech Briefs 19(4):82. Published in New Scientist magazine, 29 April 1995

- 1 2 3 Rainer F. Foelix (2010). Biology of spiders. Oxford University Press. p. 179. ISBN 0199813248.

- ↑ Peter Witt and Jerome Rovner (1982). Spider Communication: Mechanisms and Ecological Significance. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08291-X.

- 1 2 3 Nathanson, J. A. (1984). "Caffeine and related methylxanthines: possible naturally occurring pesticides". Science. 226 (4671): 184–7. doi:10.1126/science.6207592. PMID 6207592.

- ↑ Bennett Alan Weinberg, Bonnie K. Bealer (2001). The world of caffeine: the science and culture of the world's most popular drug. Routledge. pp. 237–239. ISBN 0-415-92723-4.

- ↑ Frischknecht, P. M.; Urmer-Dufek J.; Baumann T.W. (1986). "Purine formation in buds and developing leaflets of Coffea arabica: expression of an optimal defence strategy?". Phytochemistry. Journal of the Phytochemical Society of Europe and the Phytochemical Society of North America. 25 (3): 613–6. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(86)88009-8.

- ↑ Baumann, T. W.; Gabriel H. (1984). "Metabolism and excretion of caffeine during germination of Coffea arabica L". Plant and Cell Physiology. 25 (8): 1431–6.

- ↑ Guerreiro Filho, Oliveiro; Mazzafera, P (2003). "Caffeine and Resistance of Coffee to the Berry Borer Hypothenemus hampei (Coleoptera: Scolytidae)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (24): 6987–91. doi:10.1021/jf0347968. PMID 14611159.

- ↑ Araque, Pedronel; Casanova, H; Ortiz, C; Henao, B; Pelaez, C (2007). "Insecticidal Activity of Caffeine Aqueous Solutions and Caffeine Oleate Emulsions against Drosophila melanogaster and Hypothenemus hampei". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55 (17): 6918–22. doi:10.1021/jf071052b. PMID 17658827.

- ↑ Hollingsworth, Robert G.; Armstrong, JW; Campbell, E (2002). "Pest Control: Caffeine as a repellent for slugs and snails". Nature. 417 (6892): 915–6. doi:10.1038/417915a. PMID 12087394.

- ↑ JI Glendinning, NM Nelson and EA Bernays (2000). "How do inositol and glucose modulate feeding in Manduca sexta caterpillars?". Journal of Experimental Biology. 203 (8): 1299–315. PMID 10729279.

- ↑ Ronald K. Siegel (2005). Intoxication: the universal drive for mind-altering substances. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-1-59477-069-2.

- ↑ "The Influence of Chronic Exposure to Antipsychotic Medications" Published 9 March 2005.

- ↑ ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- ↑ Weird Nature - Peculiar Potions

- ↑ Worlds Weirdest Happy Hour

External links

- Nets made by spiders fed on drug-dosed flies

- Elephants on Acid: and Other Bizarre Experiments ISBN 0-15-603135-3

- LSD related death of an elephant