Elasmosaurus

| Elasmosaurus platyurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 80.5 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

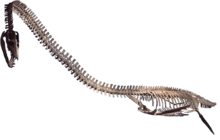

| Elasmosaurus platyurus in the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center in Woodland Park, Colorado | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Elasmosauridae |

| Genus: | †Elasmosaurus Cope, 1868 |

| Species: | †E. platyurus |

| Binomial name | |

| Elasmosaurus platyurus Cope, 1868 | |

Elasmosaurus (/ɪˌlæzməˈsɔːrəs, -moʊ-/;[1] from Greek ελασμος elasmos 'thin plate' (referring to thin plates in its pelvic girdle) + σαυρος sauros 'lizard') is a genus of plesiosaur with an extremely long neck that lived in the Late Cretaceous period (Campanian stage), 80.5 million years ago.[2]

Description

Elasmosaurus was among the largest plesiosaurs. It differs from all other plesiosaurs by having six teeth per premaxilla (the bones at the tip of the snout) and 72 neck (cervical) vertebrae.[3] The skull was relatively flat, with a number of long pointed teeth. The lower jaws were joined at the tip to a point between the fourth and fifth teeth.[3] The neck vertebrae immediately following the skull were long and low, and had longitudinal lateral crests.[4][5] Like most elasmosaurids, Elasmosaurus had around three pectoral vertebrae. The tail included at least 18 vertebrae.[4][5]

The pectoral girdle featured a long bar,[4][5] not present in juveniles. The scapula had margins of approximately equal length for the joint with the coracoid and the articular surface for the upper arm.[3] The anterior edge of the pelvic girdle was made up of three almost straight edges directed to the front and sides of the animal. The ischia, a pair of bones that formed the posterior part of the pelvis, were joined along their medial surfaces.[3] The limbs of Elasmosaurus, like those of other plesiosaurs, were modified into approximately equally sized rigid paddles.[6]

Certain aspects of the anatomy of Elasmosaurus were fairly derived among elasmosaurids, and plesiosaurs in general.[3] As noted, Elasmosaurus can be distinguished by its six premaxillary teeth and 71 cervical vertebrae.[3] Primitively, plesiosaurs and most elasmosaurids had five teeth per premaxilla. Some elasmosaurids had more: Terminonatator had nine[7] and Aristonectes had 10 to 13.[8] In addition, most plesiosaurs had fewer than 60 cervical vertebrae.[3] Aside from Elasmosaurus, plesiosaurs that exceeded 60 cervicals include Styxosaurus, Hydralmosaurus, Thalassomedon, and Albertonectes.[9] Elasmosaurus and Albertonectes are the only known plesiosaurs with more than 70 cervicals. However, Elasmosaurus had roughly the same neck length as Thalassomedon[10] because the latter has proportionally longer vertebrae.[6] The presence of the pectoral bar is also considered an advanced feature.[3] The long, low axis centrum differs from the condition seen in most other plesiosaurs, which have centra that are either shorter in length than height, or about equidimensional.[3] Styxosaurus and Hydralmosaurus also have the condition present in Elasmosaurus.[11][12] Another unusual feature of Elasmosaurus is the relatively equal lengths of the margins of the scapula, as mentioned above. Most plesiosaurs had longer margins for articulation with the coracoid than for articulation with the upper arm.[12]

Classification and species

While numerous species of Elasmosaurus have been named since its discovery, a 1999 review by Ken Carpenter showed that only one, the type species Elasmosaurus platyurus, could be considered valid. Various other species assigned to the genus are either dubious or have been classified in other genera. For example, E. serpentinus has been reclassified as Hydralmosaurus, E. morgani as Libonectes, and E. snowii as Styxosaurus.[5] By the early part of the Late Cretaceous, plesiosaurs had evolved (or had been reduced) into two distinct groups.[6] Elasmosaurus is the type genus for one of these groups, the elasmosaurids which had extremely long necks with relatively short heads, in contrast to the polycotylids which had shorter necks and relatively larger heads. Late Cretaceous elasmosaurids from the Western Interior of North America have few features that separate them and are morphologically primitive.[5] However, as noted above, Elasmosaurus and some others have some derived features. It has been suggested that Elasmosaurus was closely related to Hydralmosaurus and Styxosaurus due to these advanced features.[3]

Discovery

Elasmosaurus platyurus was described in March, 1868 by Edward Drinker Cope[13] from a fossil discovered and collected by Dr. Theophilus Turner, a military doctor, in western Kansas, United States. Although other specimens of elasmosaurs have been found in various locations in North America, Carpenter (1999) determined that Elasmosaurus platyurus was the only representative of the genus.[5]

When E. D. Cope received the specimen in early March, 1868, he had a pre-conceived idea of what it should look like, and mistakenly placed the head on the wrong end (i.e. the tail). In his defense, at the time he was an expert on lizards, which have a short neck and a long tail, and no one had ever seen a plesiosaur the size of Elasmosaurus. Although popular legend notes that it was Othniel Charles Marsh who pointed out the error, there is no factual justification for this account (see below). However, this event is often cited as one of the causes of their long-lasting and acrimonious rivalry, known as the Bone Wars. In fact, although Marsh personally collected at least one plesiosaur from Kansas, and had several more from Kansas in the Yale Peabody collection, he never published a single paper on them.[6]

Other elasmosaurus fossils have been discovered in Montana and Alaska's Talkeetna Mountains, north of Anchorage.[14]

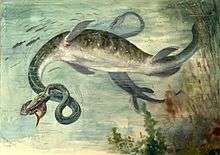

Although Cope verbally announced the discovery of Elasmosaurus platyurus in March 1868, he did not publish the "preprint" of his erroneous reconstruction of Elasmosaurus until August 1869.[15] While much smaller, long-necked plesiosaurs from the Jurassic of England were well known at the time, this was the first time anyone had ever seen a Cretaceous elasmosaur. Cope's reconstruction showed it to have a long sinuous tail like a lizard or a mosasaur. Note that while O.C. Marsh claimed to have pointed out Cope's error "20 years after the fact" in an 1890 newspaper article, it was actually Joseph Leidy who pointed out the problem in his Remarks on Elasmosaurus platyurus address at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia meeting on March 8, 1870.

Paleobiology

Elasmosaurus fossils have been found in the Campanian-age Upper Cretaceous Pierre Shale of western Kansas. The Pierre Shale represents a period of marine deposition from the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow continental sea that submerged much of central North America during the Cretaceous.[6]

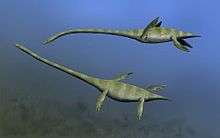

Like most plesiosaurs, Elasmosaurus was incapable of raising anything more than its head above the water as it is commonly depicted in art and media. The weight of its long neck placed the center of gravity behind the front flippers. Thus Elasmosaurus could only have raised its head and neck above the water if in shallow water, where it could rest its body on the bottom. The weight of the neck, the limited musculature, and the limited movement between the vertebrae would have prevented Elasmosaurus from raising its head and neck very high as well.[6] Nevertheless, one study found that the necks of elasmosaurs were capable of 75–177˚ of ventral movement, 87–155° of dorsal movement, and 94–176° of lateral movement, depending on the amount of tissue between the vertebrae.[16] "Swan-like" S-shape neck postures which required more than 360° of vertical flexion were not possible. The head and shoulders of the Elasmosaurus most likely acted as a rudder. If the animal moved the anterior part of the body in a certain direction, it would cause the rest of the body to move in that direction. Thus, Elasmosaurus could not have swum in one direction while moving its head and neck either horizontally or vertically in a different direction.[6]

Elasmosaurus was a slow swimmer and may have stalked schools of fish. The long neck would allow Elasmosaurus to conceal itself below the school of fish. It then would have moved its head slowly and approached its prey from below. The eyes of the animal could have had stereoscopic vision, which would help it find small prey. Hunting from below would also have helped by silhouetting the prey in the sunlight while concealing Elasmosaurus in the dark waters below. Elasmosaurus probably ate small bony fish, belemnites (similar to squid), and ammonites (molluscs). It swallowed small stones to aid its digestion.[6] In May of 2016, paleo-author Max Hawthorne presented an article addressing feeding mechanics in plesiosaurs as relates to neck length. Per Hawthorne, plesiosaurs’ long necks evolved to overcome the defense mechanisms of the fish they targeted: namely their lateral line and school formation. By approaching a school from the rear and pacing it, the marine reptile’s head (which was similar in size to its prey) created a minimal disturbance in the water. The pressure wave generated by its body was effectively masked by its long neck, causing the fish at the rear of the school to assume that the approaching plesiosaur was just another member of the school. Hawthorne stated that this evolutionary advancement allowed the predator to effectively “graze” on schools of fish, following behind without disrupting them. He also presented the theory that the sensitivity of the lateral line in a given target species correlated directly to its primary predator’s neck length. The main forage base of elasmosaurs would therefore possess the most sensitive lateral lines, hence the need for to develop a longer neck.[17] Elasmosaurus is believed to have lived mostly in open ocean. The paddles of Elasmosaurus and other plesiosaurs are so rigid and specialized for swimming that they could not have come on land to lay eggs. Thus it most likely gave live birth to its young like modern sea snakes.[6] While direct evidence of reproduction in Elasmosaurus is not yet known, the contemporaneous plesiosaur Polycotylus is known to have given birth to live young.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ "Elasmosaurus". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ↑ Carpenter, K. 2003. "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale)." High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology, 21: 421-437. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9053-0

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sachs, S. 2005. "Redescription of Elasmosaurus platyurus, Cope 1868 (Plesiosauria: Elasmosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous (lower Campanian) of Kansas, U.S.A". Paludicola 5(3): 92-106.

- 1 2 3 Brown, D. S. 1993. "A taxonomic reappraisal of the families Elasmosauridae and Cryptoclididae (Reptilia: Plesiosauroidea)". Révue de Paléobiologie, Volume Spécial, 7, 9-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Carpenter, K. 1999. "Revision of North American elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior". Paludicola 2(2): 148-173.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 320 pp.

- ↑ Sato, T. 2003. "Terminonatator ponteixensis, a new elasmosaur (Reptilia:Sauropterygia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Saskatchewan". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23(1): 89–103.

- ↑ Gasparini 2003

- ↑ Kubo, T.; Mitchell, M. T.; Henderson, D. M. (2012). "Albertonectes vanderveldei, a new elasmosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Alberta". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (3): 557–572. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.658124.

- ↑ Welles 1943

- ↑ Welles, S. P. 1943. "Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with descriptions of new material from California and Colorado". Memoirs of the University of California, 13:125-254.

- 1 2 Sachs, S. 2004. "Redescription of Woolungasaurus glendowerensis (Plesiosauria: Elasmosauridae) from the. Lower Cretaceous of Northeast Queensland". Memoirs of the Quennsland Museum, 49:215-233

- ↑ Cope, E. D. 1868. "Remarks on a new enaliosaurian, Elasmosaurus platyurus." Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 20: 92-93. (for meeting of March 24, 1868

- ↑ Newly discovered 'Loch Ness Monster; fossil gets life-size diorama in Anchorage, Alaska Dispatch News, July 25, 2015, Mike Dunham. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ Cope, E. D. 1869. "Synopsis of the Extinct Batrachia and Reptilia of North America, Part I". Transactions American Philadelphia Society New Series, 14:1-235, 51 figs., 11 pls. (pre-print dated August, 1869)

- ↑ Zammit M., Daniels, C. B. and Kear, B. P. 2008. "Elasmosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) neck flexibility: Implications for feeding strategies", Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 150(2):124-130.

- ↑ http://www.kronosrising.com/plesiosaur-long-necks/

- ↑ O'Keefe, F. R. and Chiappe, L. M. 2011 "Viviparity and K-selected life history in a Mesozoic marine plesiosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia)." Science 333(6044):870–873.

External links

-

Media related to Elasmosaurus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Elasmosaurus at Wikimedia Commons - Elasmosaurus platyurus on Oceans of Kansas

- Elasmosaurus The Plesiosaur Directory - Elasmosaurus

- Where the Elasmosaurs roam: Separating fact from fiction