Epenow

Epenow (also spelled Epanow) was a Nauset from Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts who became an early symbol of resistance to English explorers and slavers in the early 17th century.

Capture

In 1611, Epenow and Coneconam were kidnapped by Captain Edward Harlow on an island south of Cape Cod referred to as "Capoge" or "Capawick" (now called Martha's Vineyard). Capt. Harlow had already seized three Native Americans from Monhegan Island, Maine (Pechmo, Monopet, and Pekenimne, although Pechmo leaped overboard and escaped with a stolen boat cut from the stern), and at Nohono (Nantucket) he had kidnapped Sakaweston (who was to live for many years in England before fighting in the wars of Bohemia.) Altogether there were said to be twenty-nine Native Americans aboard Harlow's slaver when it arrived in England.[1]

Captivity in England

The captives had been brought to London to sell as slaves in Spain, however Harlow found that the Spanish considered Native American slaves to be "unapt for their uses." So instead, Epenow became a "wonder", a spectacle on constant public display in London. Sir Ferdinando Gorges wrote that when he met him, Epenow "had learned so much English as to bid those that wondered him 'Welcome! Welcome!'[2]

Epenow's display in London said to be inspiration of the "strange indian" mentioned by Shakespeare in Henry VIII:[3][4]

"What should you do, but knock 'em down by the dozens? Is this Moorfields to muster in? or have we some strange Indian with the great tool come to court, the women so besiege us? Bless me, what a fry of fornication is at door! On my Christian conscience, this one christening will beget a thousand; here will be father, godfather, and all together."

Gorges described Epenow as both "of a goodly stature, strong and well proportioned" as well as "a goodly man, of a brave aspect, stout, sober in his demeanor."[5]

Acquired by Gorges, Epenow was housed with another Native American captive, Assacumet, who had been captured by Captain George Weymouth in 1605 in Maine, and with whom he could communicate with some initial difficulty. With Assacumet's help, Epenow eventually became quite fluent in English.[6]

Escape

Hatching an escape plot, Epenow convinced his English captors of a gold mine on Martha’s Vineyard. Believing Epenow's fabrication, Gorges commissioned a voyage to Martha's Vineyard in 1614 under Captain Nicholas Hobson, accompanied by Epenow as a guide, translator, and pilot, together with his fellow captives Assacomet and Wanape. Wanape died soon after arriving in the New World. Upon arriving to Epenow's native island, the ship was peacefully greeted by a company of Wampanoags, including some of Epenow's brothers and cousins, whom Epenow quickly and quietly conspired with. Captain Hobson entertained the visitors to his ship, and invited them to return the next morning with trade goods. Not trusting Epenow, Hobson made sure he was accompanied at all times by three guards, and clothed him with long garments that could be easily grabbed.[7]

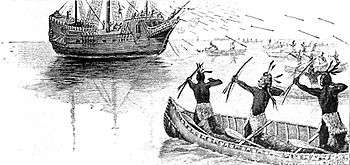

His friends returned in twenty canoes as promised, but did not board the ship. The captain, his invitations ignored, called Epenow to come out from the forecastle to translate. Epenow called in English for his friends to come aboard, but then lunged to jump overboard. Hobson's men managed to grab him, but Epenow being "a strong and heavy man" managed to dive overboard under cover of arrows shot from the canoes. Both sides took heavy casualties; Hobson's musketeers killed and wounded some, and Hobson and many of his crew were injured in the battle. They returned to England empty handed.[8][9]

Later career and legacy

Epenow became an important source of anti-English resistance when the Plymouth colonists arrived six years later,[10] and there is evidence that he became a sachem.[11][12]

Epenow met with visiting Englishman Captain Thomas Dermer in 1619 in a peaceful meeting on Martha's Vineyard, and laughed as he told the story of his escape from captivity. But on Dermer's second visit in 1620, shortly before the arrival of the Mayflower, Epenow's warriors attacked the captain and his men, and took captive his traveling companion, the celebrated Squanto, before turning him over to Massasoit (the leading Wampanoag sachem). Some of Epenow's company were slain, but all but one of Dermer's crew were killed, and Dermer, severely wounded with fourteen wounds, escaped to Virginia where he died soon afterward.[13][14][15][16]

Fictional representation

Native Canadian actor Eric Schweig portrayed Epenow in Disney's 1994 live action adventure drama film Squanto: A Warrior's Tale.

See also

- Nemattanew, Epenow's contemporary active in Virginia.

References

- ↑ Drake, Samuel Gardner. Biography and History of the Indians of North America. Boston, 1835.

- ↑ Banks, Charles. The History of Martha's Vineyard, Vol. I. Edgartown, MA: Dukes County Historical Society, 1966, p. 68.

- ↑ Vaughan, Alden T. Transatlantic encounters: American Indians in Britain, 1500-1776. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- ↑ Lee, Sidney. The Call of the West. Scribner's Magazine, July 1907. Page 322.

- ↑ Banks, Charles. The History of Martha's Vineyard, Vol. I. Edgartown, MA: Dukes County Historical Society, 1966, p. 68.

- ↑ Banks, Charles. The History of Martha's Vineyard, Vol. I. Edgartown, MA: Dukes County Historical Society, 1966, p. 68.

- ↑ Drake, Samuel Gardner. Biography and History of the Indians of North America. Boston, 1835.

- ↑ Burrage, Henry Sweetser. The Beginnings of Colonial Maine: 1602-1658

- ↑ Steele, Ian Kenneth and Rhoden, Nancy Lee. The Human Tradition in Colonial America. Wilmington DE: Scholarly Resources, 1999.

- ↑ Steele, Ian Kenneth and Rhoden, Nancy Lee. The Human Tradition in Colonial America. Wilmington DE: Scholarly Resources, 1999.

- ↑ Dempsey, Jack. Good News from New England: And Other Writings on the Killings at Weymouth 2001.

- ↑ Philbrick, Nathaniel. Mayflower: a story of courage, community, and war

- ↑ Adams, Charles Francis. Three Episodes of Massachusetts History: The Settlement of Boston, Volume 1

- ↑ Baxter, James Phinney. Sir Ferdinando Gorges and his Province of Maine.

- ↑ Burrage, Henry Sweetser. The Beginnings of Colonial Maine: 1602-1658

- ↑ Drake, Samuel Gardner. Biography and History of the Indians of North America. Boston, 1835.