Ether Dome

|

Ether Dome, Massachusetts General Hospital | |

|

The inside of the dome as viewed from the surgical theatre. | |

| |

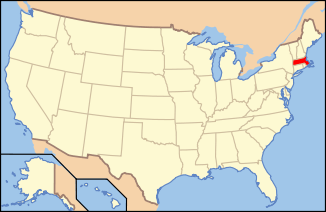

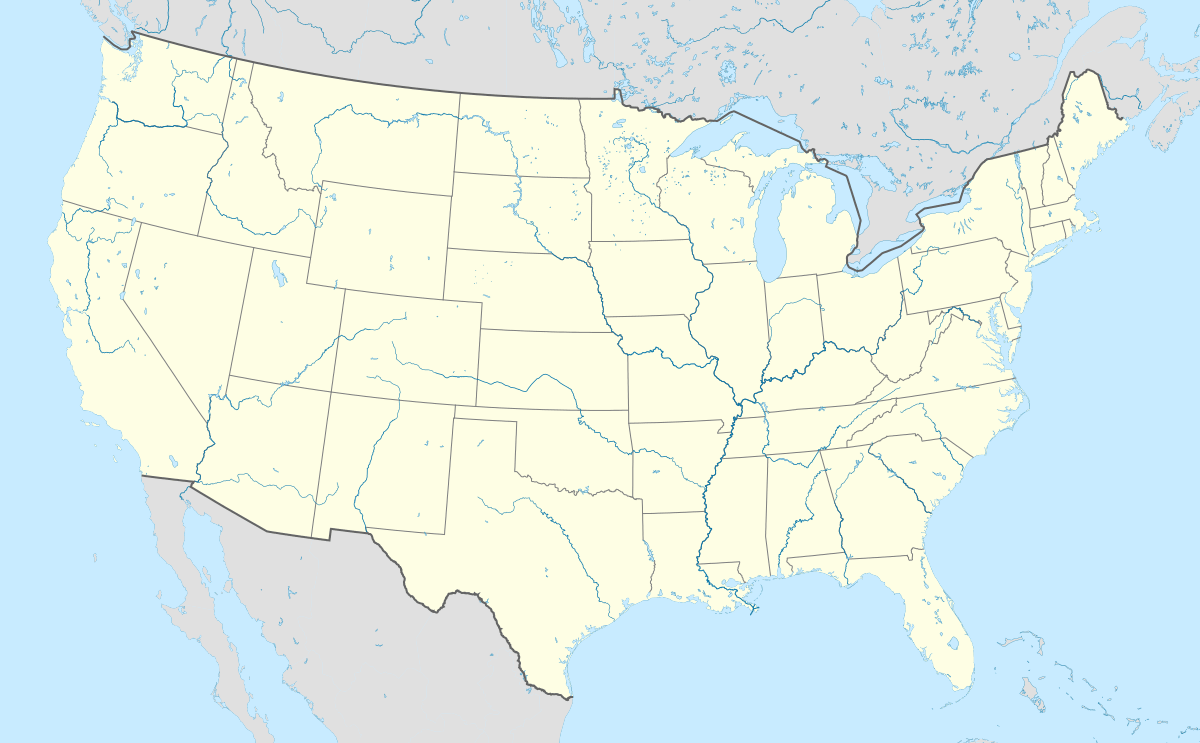

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°21′48.70″N 71°4′4.30″W / 42.3635278°N 71.0678611°WCoordinates: 42°21′48.70″N 71°4′4.30″W / 42.3635278°N 71.0678611°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1846 |

| Architect | Charles Bulfinch; George Perkins; Alexander Parris |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000366[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | January 12, 1965[2] |

The Ether Dome is a surgical operating amphitheater in the Bulfinch Building at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. It served as the hospital's operating room from its opening in 1821 until 1867. It was the site of the first public demonstration of the use of inhaled ether as a surgical anesthetic on October 16, 1846, otherwise known as Ether Day. Crawford Long, a surgeon in Georgia, had previously administered sulfuric ether in 1842, but this went unpublished until 1849.[3][4] The Ether Dome event occurred when William Thomas Green Morton, a local dentist, used ether to anesthetize Edward Gilbert Abbott. John Collins Warren, the first dean of Harvard Medical School, then painlessly removed part of a tumor from Abbott's neck. After Warren had finished, and Abbott regained consciousness, Warren asked the patient how he felt. Reportedly, Abbott said, "Feels as if my neck's been scratched". Warren then turned to his medical audience and uttered "Gentlemen, this is no Humbug".[5][6] This was presumably a reference to the unsuccessful demonstration of nitrous oxide anesthesia by Horace Wells in the same theater the previous year, which was ended by cries of "Humbug!" after the patient groaned with pain.[7]

History

The End of Pain in Surgery

In 1844, Hartford dentist Horace Wells noticed the painkilling effects of nitrous oxide at an event where volunteers inhaled the gas and then stumbled around and acted silly. Such affairs were known as “frolics.”

Wells used nitrous oxide in his dental practice for the painless extraction of teeth. In 1845 he attempted to demonstrate his discovery in Boston. The test failed, probably because the dose was inadequate. Soundly ridiculed, Wells became deeply discouraged.

William T.G. Morton, a partner in Wells’ practice, learned the technique and began experimenting on his own. Morton’s interest in using the method for surgical anesthesia was inspired by Wells, but he also benefited from conversations with Charles T. Jackson, a professor of chemistry at Harvard, who advised him to use a higher grade of sulphuric ether. Jackson seemed to know that the gas could be effective in surgery, but he made no effort to apply his knowledge.

Ether Day

The Operation

With the help of MGH surgeon Henry Jacob Bigelow, Morton persuaded Warren to allow him to try his technique on a surgical patient. The trial took place in the Ether Dome on October 16, 1846. The patient – a young printer named Gilbert Abbott, who had a vascular neck tumor- announced that he had felt a scratching sensation, but no pain. John Collins Warren turned to the observers and proclaimed, “Gentlemen, this is no humbug.” Bigelow immediately published an article describing the event and the news quickly travelled to Europe and other parts of America.

The Patient

Among the revolving door of noted physicians and important figures supposedly present on the historic Ether Day, one figure remains constant: Edward Gilbert Abbott, the man upon whom the ether and surgery was administered. Abbott was born in Middlesex County, MA in September 1825. His parents, victims of phthisis, left him an orphan in 1832. After a career as a printer and editor, in September 1846, he went in to receive a medical evaluation for a tumor he'd had on the left side of his jaw, even though it had been present his whole life and did not cause him any pain.

Abbott was given enough ether to make him fall unconscious; he left the hospital with an unremarkable change in the size of the tumor. He was assured - as he probably knew, that it was a benign growth and that he had contributed greatly to the history of medicine. He died in 1855 at the age of 30, leaving behind a wife, a daughter, and a son. The Boston Herald included a mere three sentence summary of his life and descendants in its December 1 issue.[8]

Legacy

The Ether Controversy

Wells, Jackson and Morton each claimed credit for the innovation. Jackson and Morton tangled in a bitter legal dispute and pamphleteering war that lasted 20 years. Jackson died insane at McLean Asylum in Belmont, Massachusetts.

In 1868 Morton read a newspaper item asserting that Jackson deserved the lion’s share of credit. He became feverish, threw himself into a pond in New York’s Central Park and died, probably from a stroke, soon thereafter.

Wells left the practice of dentistry and his family and went to New York, where he was arrested for throwing acid on prostitutes. He killed himself in jail by slashing an artery after taking chloroform.

Meanwhile, a small-town Georgia doctor named Crawford Long had performed operations using ether anesthesia as early as 1842, but didn’t publish his results until 1849, so he received no credit for the innovation.[9]

Present Day

Today, the Ether Dome is actively used for daily medical conferences and presentations. When not in use, it is open to the public as a National Historic Landmark.[10] There is a contemporary recreation of the historic event by Warren and Lucia Prosperi seen in the Ether Dome. In addition, there is a mummy and authentic surgical instruments in cases. The mummy was recently studied by CAT scan.[11] More information about the ether story, including period ether inhalers and a 1930s silent film recreation of ether day, is on view at the Paul S. Russell, MD Museum of Medical History and Innovation, also at the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Presently, Massachusetts General Hospital also uses the occasion of the Ether Day to honor their employees' dedication. Held annually, the ceremony commemorates both the etherization event as well as employees who that year reached 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55 or 60 years of service. The event occurs under the Bullfinch Tents and takes note of each employee's contributions to the hospital's mission statement. Employees who have worked over 20 years are also honored at the Ether Day Dinner, held around the same time each year at the Westin Boston Waterfront Hotel.[12]

Features

Curated Displays

Robert Hinckley's The First Operation with Ether

Robert Cutler Hinckley was born in either Northampton or Boston on April 3, 1853. As a teen, his parents took him to Paris for formal training in art. In his 20 years there, he trained under Charles Auguste Emile Durand, a renowned portrait artist. Hinckley began work on The First Operation with Ether while in Paris in 1882. This is one of two noted paintings regarding this event; the other is the Prosperis' Ether Day (2001). Hinckley himself had not been yet born when Ether Day occurred, and it is likely that he was never acquainted with anyone who was present.[13]

Hinckley researched the event for nearly fifteen years (the painting was done from 1881-1894) attempting to ascertain every detail, particularly who was present and participating. He used light and line to draw attention on the surgery; the side wall of the gallery draws a clear diagonal line which ends at the surgeon Warren’s head. Morton’s ether inhaler reflects light so as to make the sponge contained inside visible. Abbott's shirt as well as the cloth and the bowl on the table are starkly white, directing the eye to the operation. However, the viewer is shielded from the point of incision and from any blood, lessening the impact of the image.

A controversy surrounding the painting revolves around those who are painted into it. Hinckley includes Charles Hosea Hildreth, surgeon Abel Lawrence Peirson, surgeon Jonathan Mason Warren, and physician William Williamson Wellington - all individuals who are highly unlikely to have been present during the operation. Furthermore, he did not include two surgeons who were very likely there - Samuel Parkman and George Hayward.[13] The painting is now located in the Countway Medical Library at Harvard Medical School.

Warren and Lucia Prosperi's Ether Day, 1846

As the 150th anniversary of the first public demonstration of the use of ether anesthesia on October 16, 1846, approached and preparations for the celebration at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) began, it was recognized that a proper commemorative painting was needed. The famous Hinckley image, reproduced many times, was painted 27 years after the event. It is the product of the artist’s imagination and portrays, among the actual participants, others who were not really in attendance but are nonetheless “painted into history.” Subsequent research has provided a more accurate list of the witnesses.

Accordingly, in 2000 the clinical staff of the MGH voted to commission Warren and Lucia Prosperi, well known for their historically accurate paintings, to “do it right.” Artists Warren and Lucia Prosperi created this mural between 2000 and 2001, painting on site in the Ether Dome. To represent the historic operation as realistically as possible, a group of doctors and their spouses, working with the Prosperis, searched out photographs, daguerreotypes, and portraits of the participants. They also consulted vintage photographs and artifacts from the MGH Archives and Special Collections. The theatre department of Emerson College was engaged to provide period costumes and makeup. Much of the original paraphernalia—the ether flask, the operating chair, and various furnishings of the amphitheater—was still in our museum and available for the scene.

On one Sunday in January, 2001, a group convened to re-enact the historic event on site at the original location, MGH’s Ether Dome, with the Boston press corps in attendance. Two hours were spent debating the likely orientation of the operating chair and instrument table and who would have been standing where so that everyone, including the students in the gallery, could see the action. Many configurations were tested, and The Prosperis photographed hundred of photographs a cast of 20 men, mostly MGH physicians, who gathered in the Ether Dome in January 2000 dressed in period costumes. Finally the scene was set and recorded.

Over the course of 2001, Warren Prosperi created the painting with its life-size figures on site in the Ether Dome, allowing visitors to witness the emergence of the historic re-enactment. This painting now hangs on the front wall of the amphitheater.

One additional footnote: a special unveiling of Ether Day, 1846 was planned for the meeting of the Halsted Society at the Massachusetts General Hospital on September 12, 2001. Because of the infamous events of the previous day, that meeting was canceled (but held two years later).

As the mural depicts, in the years before antiseptic and aseptic surgery, a surgeon typically operated in a frock coat as was appropriate for the dignity of his profession. The ivory or ebony handles of his surgical instruments signaled his status but made the instruments difficult to clean. Sterile surgery was not achieved at the MGH until the 1880s.[14][15][16]

Mummy (The Hospital’s Oldest Patient)

On May 4, 1823, Massachusetts General Hospital received an Egyptian mummy from the city of Boston, complete with painted wooden inner and outer coffins. The ensemble had been given to the city by Jacob Van Lennep, a Dutch merchant living in the Greek city of Smyrna in the early 19th century. It is thought that Mr. Van Lennep, who was also the Counsel General of the Netherlands, bought the mummy as a gift to Boston as a way to impress his native New England in-laws.

The mummy arrived in Boston on April 26, 1823, on the British ship the Sally Ann[17] and was the first complete Egyptian burial ensemble in America. He was placed under the care of the ship’s captain, Robert B. Edes, along with Bryant P. Tilden, Esq., who ultimately made the decision to give the mummy to Massachusetts General Hospital, whose trustees accepted the gift as “an appropriate ornament of the operating room,” while also hoping to exhibit the mummy to raise funds for the hospital. The fledgling hospital, which had opened its doors just two years earlier, was still in need of operating funds that would help it better serve the sick and indigent individuals for whom it had been chartered to provide care. The mummy would help raise those needed funds.

Shortly after his arrival, the mummy was put on display at "Mr. Doggett’s Repository of Arts" in Boston, where hundreds of people paid $0.25 to see the first complete human Egyptian mummy in the U.S. That fall, the mummy went on a year-long (1823 to 1824) multi-city tour of the East Coast, raising even more money for the hospital. Upon his return, he was placed in the Ether Dome where he subsequently witnessed more than 6,000 surgeries, including the famous first successful demonstration of surgery under anesthesia on October 16, 1846.

In 1823, John Collins Warren partially unwrapped and examined the mummy. He then published the first American treatise about mummies and mummification. The mummy spent much of the late 19th century at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The mummy’s outer coffin has been at the George Walter Vincent Museum in Springfield, MA since 1932.

More than a century later the hospital learned just who the mummy was. In 1960, Dows Dunham, curator emeritus of the Department of Egyptian Art at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, examined and translated the hieroglyphics on the mummy’s coffin. Hailing from the 26th Dynasty (663-525 BC) or later, the mummy now had a name – Padihershef, meaning “He whom the god Hershef has given.” and a birthplace – Thebes; and an occupation—stonecutter. Newer medical information tells us that Padihershef, or "Padi", was probably between 20 and 30 years of age and was not a stonecutter at all. Rather, he was "tomb finder," or prospector, someone who looked for spaces in the Theban necropolis that could serve as burial spaces.[17]

Padihershef’s remains have been studied by means of x-rays and CT scans.[11] In 2013, a donor provided funds for the mummy’s restoration. During the procedure, Padihershef was given a full-body CT scan overseen by Massachusetts General Hospital’s radiologist Rajiv Gupta. This scan, which provided more than 20,000 scans that were then assembled into 3D renderings of his body. Many of these are replicated in the report prepared by forensic pathologist Jonathan Elias, PhD, of AMSC Research, a mummy research consortium.

One of the outcomes of the project includes a CT facial reconstruction of Padihershef. Using the scans, 3D facial recognition software and a thorough knowledge of mummy forensics, Elias' group undertook a thorough analysis based on all these factors and using a 3D skull model, developed a representation of what Padi may have looked like in life.

The mummy Padishershef has borne witness to many medical milestones during his 190 years in the Massachusetts General Hospital’s Ether Dome. Over the decades, visitors to the room have been greeted silently by this unusual host, standing nestled in his beautifully decorated coffin, and often wondered just who he was and how he came to reside at the hospital.

Until this most recent examination, little was known about his life before his death. John Collins Warren, MD, cofounder of MGH and its first surgeon, had performed a post-mortem on "Padi" when he first came to the MGH, which included uncovering the mummy’s head, as it remains today. In 1931, and again in 1977, X-rays were taken of Padi in his case, which provided a little more insight into his health. Growth lines show that Padi was so ill as a child that his growth stopped for some time before he was well again. Bone damage reveals that he suffered from arthritis. The extensive report included here provides many details of Padi's life that were unknown to us until his March 2013 scanning examination.

Padi has been restored twice before: once in the 1980s and again in 2002. Salt deposits that build up from the embalming elixir have formed on the exposed portions of Padi’s face and head need to be removed periodically.[17] The restoration also included replacing the old grass and wood case with the current climate-controlled enclosure.[9]

The Apollo Belvedere Statue

The plaster statue of Apollo in the Ether Dome was given to the MGH by statesman and orator, Honorable Edward Everett in March 1845. In exchange, the hospital trustees presented to him “their grateful acknowledgments for his beautiful gift, valuable as a memorial, that, amidst his arduous public duties in a foreign country, Mr. Everett feels an undiminished interest in the charitable institutions of his native land.”

The displayed work is a copy of the original Apollo Belvedere, a sculpture unearthed in Rome during the Renaissance. Napoleon looted Rome in the early 19th century and took the Apollo Belvedere from the Vatican to the Louvre in Paris. where the statue that is on display was crafted. The Louvre made and sold plaster casts of the statue, one of which Everett bought and shipped back to Boston. The English sea captain and novelist Frederick Marryat decried, while on a visit to Everett’s home, where the statue was draped to cover its near-nakedness, a few years before the donation, the covering as an example of the prudishness of otherwise educated and open-minded Americans.[18][19]

The Skeleton

The teaching skeleton hanging in the Ether Dome can be seen in the background of daguerreotypes showing the administration of ether anesthesia in 1847. Such skeletons were a common feature in hospitals and medical schools in the 19th century.

The First Operating Room of the MGH

The Ether Dome served as an operating theatre from 1821 to 1867, when a new surgical building was constructed. Operating rooms built before electricity were typically located on the top floor of a building to take advantage of available light. Before surgical anaesthesia the location was also helpful to muffle the screams of patients for those on the floors below. Because pain often induced shock, surgeons of the day prided themselves on the speed in which they could amputate an arm or a leg. Ninety seconds was considered a good time. Two 19th- century operating chairs famously known as Bigelow Operating chair was built in 1854, are located in the display area behind the seating tiers. Their red velvet upholstery was apparently intended to make bloodstains less visible. It was created in light of this discovery; it was the first of its kind without restraints and had ivory and wooden handles that could be used to position the unconscious, anesthetized patient. The chair quickly fell out of use over the next few decades, however, as it was made from leather rather than metal, which can be sterilized more easily.

After 1867 the Ether Dome served at different times as a dormitory for nurses, a dining hall and a storage area. The hospital commemorated the historical significance of the space in 1896 on the 50th anniversary of the first public demonstration of surgical anesthesia. The Ether Dome was designated a National Historic Site in 1965.

While the words “Operating Room” still appear inside the door to the closet on the right of the painting, today the room serves as a place for meetings and lectures. The steel tiers with individual chairs date from about 1930, when fire regulations required the replacement of the old wooden bench seating. The names of the chairs have no known significance – it is likely that hospital donors were given the opportunity to name a chair after a favorite figure from MGH history.

Ether Dome Sublevel Exhibit

Located through small doors on either side of the Ether Dome theater or through a closed door at the bottom of a steep, downwards stairway behind the top row of the theater, there is an exhibit of various Ether Day artifacts and information, including quotes from the Ether Day event. In the round room under the seats of the Ether Dome theater, the exhibit is designated as the “G. H. Gay Ward, Memorial of George Henry Gay” by a shiny, gold plaque. On the walls there are drawings and paintings of notable figures, such as Dr. William T. G. Morton, and pictures of quotes, like “We have conquered pain.” Alongside the exhibited pictures and quotes, there are artifacts like an operating chair and the wedding clothes of William T. G. Morton, which represent an evidence of wealth and a veneration of ether. The hidden crescent-shaped corridor is a significant part of the Ether Dome exhibit that rarely gets the same attention. With a normal diabetes office inside of the small doors, it is easy to see how the Ether Dome's second half can be mistaken for a locked room or closet behind the Ether Dome.

Architecture

The Ether Dorm is the oldest type of today's operation room. The dome's architecture resembles that of a courtroom or a theatre house where surgeries were performed at the centre of the dome. An audience of surgeons and doctors can witness the surgeries and therefore the room has a number of seats arranged in the style of an amphitheater so all spectators can see the details of the medical procedures performed by the surgeons in charge. A visitor to the room today can see the names of famous doctors crafted on the seats. Hence, since the implementation of anesthesia was not a common practice in these days, the dome was placed at the top of the building to seclude screaming patients from other sections of the hospital. The location of the dome also and the huge glass ceiling and windows let in enough light for the operations to be visible to all. Nowadays, the concept of the dome's architecture is still there, but for hygiene purposes the spectators' section is separated from the main OR by a huge glass. The Dome in its original theatre style architecture has turned into a historical sight for students of medicine and interested spectators.

Gallery

-

Inside the Ether Dome

-

Outside view as photographed from the grounds

-

Operating theater tiered seating under the dome

-

Apollo statue by the entrance

-

Operating theater and seating

-

The MGH Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine traces its roots back to the October 16, 1846 public demonstration of medical ether.

-

View from the seats of the theater

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Boston

- National Register of Historic Places listings in northern Boston, Massachusetts

- Ether Monument

- Massachusetts General Hospital

- Diethyl Ether (Anesthetic Use)

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Ether Dome, Massachusetts General Hospital". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ↑ Madden, M. Leslie (May 14, 2004). "Crawford Long (1815-1878)". New Georgia Encylcopedia. University of Georgia Press. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Crawford W. Long". Doctors' Day. Southern Medical Association. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Fenster, J. M. (2001). Ether Day: The Strange Tale of America's Greatest Medical Discovery and the Haunted Men Who Made It. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019523-6.

- ↑ The Roots of Critical Care, Jennifer Nejman Bohonak, Massachusetts General Hospital Magazine, 2011

- ↑ "Horace Wells". Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ "Edward Gilbert Abbott: Enigmatic Figure of the Ether Demonstration" (PDF).

- 1 2 The Ether Dome at Massachusetts General Hospital: An Icon of Medical Innovation. Massachusetts General Hospital.: Massachusetts General Hospital.

- ↑ "National Historic Landmarks Program: Ether Dome, Massachusetts General Hospital". Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- 1 2 http://www.bostonglobe.com/2013/03/06/mummy-gets-scan-mgh/XsWR7eqweBg61bI0TLmW6N/story.html

- ↑ http://www.massgeneral.org/anesthesia/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=4995. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 "A Tale of Two Paintings: Depictions of the First Public Demonstration of Ether Anesthesia".

- ↑ Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde. Boston Medical Library in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Boston: Stuttgart. 1993.

- ↑ Todres, M. Gionfriddo. A conversation with Warren and Lucia Prosperi.

- ↑ Kitz, R.J. (2002). This is no humbug. Boston: Massachusetts General Hospital.

- 1 2 3 "Uncovering the Life of Padihershef". Massachusetts General Hospital. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- ↑ "The Ether Dome: The restoration of an icon". neurosurgery.mgh.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- ↑ MGH HOTLINE. Massachusetts General Hospital. August 19, 2011 – via http://www.massgeneral.org/News/assets/pdf/htl08192011.pdf.

External links

- The Ether Dome: The restoration of an icon

- Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care: Our Story

- Ether Monument Wikipedia