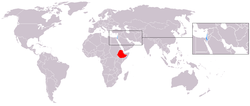

Ethiopia–Israel relations

|

|

Ethiopia |

Israel |

|---|---|

Ethiopia–Israel relations are foreign relations between Ethiopia and Israel. Both countries re-established diplomatic relations in 1992. Ethiopia has an embassy in Tel Aviv; the ambassador is also accredited to the Holy See, Greece and Cyprus. Israel has an embassy in Addis Ababa; the ambassador is also accredited to Rwanda and Burundi. Israel has been one of Ethiopia's most reliable suppliers of military assistance, supporting different Ethiopian governments during the Eritrean War of Independence.

In 2012, an Ethiopian-born Israeli, Belaynesh Zevadia, was appointed Israeli ambassador to Ethiopia.[1]

History

Royal Era

During the imperial era, Israeli advisers trained paratroops and counterinsurgency units belonging to the Fifth Division (also called the Nebelbal, 'Flame', Division).[2] In December 1960, a section of the Ethiopian army attempted a coup whilst the Emperor Haile Sellassie I was on a state visit in Brazil. Israel intervened, so that the Emperor could communicate directly with general Abbiye. General Abbiye and his troops remained loyal to the Emperor, and the rebellion was crushed.[3]

In the early 1960s, Israel started helping the Ethiopian government in its campaigns against the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF).[2][3] The Ethiopian government portrayed the Eritrean rebellion as an Arab threat to the African region, an argument that convinced the Israelis to side with the Ethiopian government in the conflict.[4] Israel trained counter-insurgency forces and the Governor General of Eritrea, Asrate Medhin Kassa, had an Israeli Military Attaché as his advisor. An Israeli colonel was put in charge of a military training school at Decamare and the training of the Ethiopian Marine Commando Forces.[2][3] By 1966, there were around 100 Israeli military advisors in Ethiopia.[3] The Ethiopian-Israeli cooperation had impacts on the discourse of the Eritrean rebel movements, which increasingly began to use anti-Zionist rhetoric. It also enabled the Eritreans to mobilize material support from the Arab and Islamic world.[5]

The Israeli perception of the war in Eritrea as part of the Arab-Israeli conflict was reinforced when reports of links between the ELF and Palestine Liberation Organization emerged after the Six Days War.[6]

Parallel to the war in Eritrea, Israel was accused of aiding the Ethiopian government in crushing the Oromo resistance.[5]

In 1969 the Israeli government had proposed the formation of an anti-Pan-Arab alliance consisting of the United States, Israel, Ethiopia, Iran and Turkey. Ethiopia rejected the proposal. In 1971, the Israeli Chief of Staff Bar Lev made a visit to Ethiopia, during which he presented proposals for deepening of Israeli-Ethiopian cooperation. The Ethiopians turned down the Israeli proposals but nevertheless, Ethiopia became internationally accused of having given concessions to Israel for setting up Israeli military bases on Ethiopian islands in the Red Sea. Ethiopia consistently denied all such accusations.[7]

Israel offered Ethiopia military assistance in the event of a Yemeni take-over of the islands, but Ethiopia turned down the offer fearing a political backlash. Still, Ethiopia was attacked at the 1973 OAU summit in Addis Abeba by the Libyan delegation, accusing Ethiopia of allowing the build-up of Israeli bases on its territory. At the summit the Algerian president Houari Boumediène called on Ethiopia to break its relations with Israel. In return, Boumediène offered to use his political leverage to freeze Arab support for the ELF.[7][8]

The allegations of possible Israeli military bases on the islands of the Eritrean coast surfaced again soon thereafter, at a summit of Foreign Ministers of Islamic countries, held in Benghazi, Libya. The Benghazi meeting condemned Ethiopian-Israeli cooperation, and pledged support for the ELF.[7][9]

Ethiopian Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold began seeking political support for breaking relations with Israel after the OAU summit. After long discussions, the cabinet voted to sever diplomatic links with Israel. The decision was however censored by a veto from the Emperor. At the time of the October 1973 war, many African states severed their relations with Israel. This, and Arab threats of a crippling oil embargo,[10] put pressure on the Emperor to withdraw his veto, and on October 23, 1973 Ethiopia severed its diplomatic relations with Israel. The break of relations with Israel caused the United States to tone down its support to Imperial rule in Ethiopia.[8]

Mengistu rule

Even after Ethiopia broke diplomatic relations with Israel in 1973, Israeli military aid continued after the Derg military junta came to power and included spare parts and ammunition for U.S.-made weapons and service for U.S.-made F-5 jet fighters.[2] Israel also maintained a small group of military advisers in Addis Ababa.[2]

In 1978, however, when the Israeli Minister of Foreign Affairs Moshe Dayan admitted that Israel had been providing security assistance to Ethiopia, Mengistu Haile Mariam expelled all Israelis so that he might preserve his relationship with Arab states such as Libya and South Yemen.[2] Although, Addis Ababa claimed it had terminated its military relationship with Israel, military cooperation continued. In 1983, for example, Israel provided communications training, and in 1984 Israeli advisers trained the Presidential Guard and Israeli technical personnel served with the police. Some Western observers believed that Israel provided military assistance to Ethiopia in exchange for Mengistu's tacit cooperation during Operation Moses in 1984, in which 10,000 Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jews) were evacuated to Israel.[11] In 1985 Israel reportedly sold Addis Ababa at least US$20 million in Soviet-made munitions and spare parts captured in Lebanon. According to the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF), the Mengistu regime received US$83 million worth of Israeli military aid in 1987, and Israel deployed some 300 military advisers to Ethiopia. Additionally, the EPLF claimed that thirty-eight Ethiopian pilots had gone to Israel for training.[2]

As Mengistu's allies in the Socialist Bloc went into a state of crisis and division, Ethiopia began to put more emphasis on relations with Israel.[12] In 1989 formal diplomatic relations were reinstated.[13] In late 1989, Israel reportedly finalized a secret agreement to provide increased military assistance in exchange for Mengistu's promise to allow Ethiopia's remaining Beta Israel to immigrate to Israel. In addition, the two nations agreed to restore diplomatic relations and increase intelligence cooperation. Mengistu apparently believed that Israel, unlike the Soviet Union, whose military advisers emphasized conventional tactics, could provide the training and matériel needed to transform the Ethiopian army into a counterinsurgency force.[2]

During 1990 Israeli-Ethiopian relations grew stronger. According to the New York Times, Israel supplied 150,000 rifles, cluster bombs, ten to twenty military advisers to train Mengistu's Presidential Guard, and an unknown number of instructors to work with Ethiopian commando units. Unconfirmed reports also suggested that Israel had provided the Ethiopian Air Force with surveillance cameras and had agreed to train Ethiopian pilots.[2]

Commercial relations

Trade relations between Ethiopia and Israel have grown over the years. In the early 1980s, Dafron, an Israeli notebook manufacturer, won a government contract to market 2 million notebooks to Ethiopia.[14] Israel imports Ethiopian sesame, coffee, grains, skins and hides, spices, oilseed and natural gum.[15]

Ethiopian Jews

In return for this aid, Ethiopia permitted the emigration of the Beta Israel. Departures in the spring reached about 500 people a month before Ethiopian officials adopted new emigration procedures that reduced the figure by more than two-thirds. The following year, Jerusalem and Addis Ababa negotiated another agreement whereby Israel provided agricultural, economic, and health assistance. Also, in May 1991, as the Mengistu regime neared its end, Israel paid US$35 million in cash to allow nearly 15,000 Beta Israel to emigrate from Ethiopia to Israel.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ Foreign Ministry names first Israeli of Ethiopian origin as ambassador

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ethiopia-Israel

- 1 2 3 4 Pateman, Roy. Eritrea: even the stones are burning. Lawrenceville, NJ [u.a.]: Red Sea Press, 1998. pp. 96–97

- ↑ Iyob, Ruth. The Eritrean Struggle for Independence: Domination, Resistance, Nationalism, 1941-1993. African studies series, 82. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. p. 108

- 1 2 Lata, Leenco. The Ethiopian State at the Crossroads: Decolonisation and Democratisation or Disintegration? Lawrenceville, N.J. [u.a.]: Red Sea, 1999. pp. 95–96

- ↑ Lefebvre, Jeffrey Alan. Arms for the Horn: U.S. Security Policy in Ethiopia and Somalia, 1953-1991. Pitt series in policy and institutional studies. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991. p.

- 1 2 3 Spencer, John H. Ethiopia at Bay: A Personal Account of the Haile Selassie Years. [S.l.]: Tsehai Pub, 2006. pp. 322–323

- 1 2 Tiruneh, Andargachew. The Ethiopian Revolution, 1974–1987: A Transformation from an Aristocratic to a Totalitarian Autocracy. LSE monographs in international studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. pp. 31–32

- ↑ Situation in the Horn; HIM's Visit

- ↑ Getachew Metaferia, Ethiopia and the United States: History, Diplomacy, and Analysis p. 72.

- ↑ Ethiopian-Israeli accord eases Jewish emigration

- ↑ Africa - Ethiopia - General Information

- ↑ Tiruneh, Andargachew. The Ethiopian Revolution, 1974-1987: A Transformation from an Aristocratic to a Totalitarian Autocracy. LSE monographs in international studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. p. 360

- ↑ Saying goodbye to Israel's beloved notebook, Haaretz

- ↑ "Trade in Ethiopia: An Overview". Embassy of Ethiopia in Israel. Retrieved 2012-05-07.