Eugène Farcot

| Henri-Eugène-Adrien Farcot | |

|---|---|

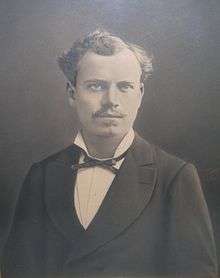

The horologist in his youth | |

| Born |

20 February 1830 Sainville, France |

| Died |

14 March 1896 (aged 66) Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Horologist, inventor, businessman |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Spouse(s) | Pauline Le Blond (1836-1898) |

| Children | Marguerite Farcot (1858-1890) Charles-Louis-Eugène Farcot (1860-1881) |

| Parent(s) | Louis François Désiré Farcot and Emelie Delafoy |

Henri-Eugène-Adrien Farcot (Sainville, February 20, 1830 – Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, March 14, 1896) was a French clock-maker, inventor, mechanical-engineer, aeronaut, occasional writer and one of the most celebrated conical pendulum clock makers.

In 1853 he established the Manufacture d’horlogerie E. Farcot with headquarter (from 1855) in rue des Trois-Bornes, 39, Paris, wherein he worked until his retirement in the late 1880s, same as the successors, his son-in-law the Belgian Henri-Charles Wandenberg, or Vandenberg, until December 1903 and Paul Grenon (Wandenberg's nephew) until 1914. Between October 1855-March 1856 the company's name changed to Farcot et Cie, and in 1887 it was renamed Farcot et Wandenberg, despite the partnership was officially constituted in April 1890.

Throughout his career path, Eugène Farcot was awarded with one honorable mention and four medals in the following expositions: Besançon 1860 (bronze), London 1862 (honorable mention), Paris (1863 bronze, 1867 bronze & 1878 silver), as well as Henri Wandenberg, both with a silver medal in Paris 1889 and a gold medal in Paris 1900.

He exhibited his products at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, Exposition Universelle (1867) in Paris, Centennial Exposition (1876) in Philadelphia, and for the last time at the Exposition Universelle (1878) in Paris. In addition to clock-making, he was a member of the Société aérostatique et météorologique de France and the also defunct Chambre syndicale d'horlogerie de Paris. The Musée Farcot, in Sainville, preserves memories of his life, travels and work.

Patents

Of the eighteen patents registered to his name between 1855 and 1886, 16 are linked to horology. They are by chronological order:

|

|

Monumental conical pendulum clock series

A class of its own among the conical pendulum clocks are the Farcot monumental timepieces commercialized between 1862 and 1878. When the model debuted at the London International Exhibition of 1862, it was presented as the first application of the conical pendulum to statuary.[1] In addition to the British capital, it was also displayed in the Paris Exposition des beaux-arts appliqués à l’industrie (1863), as well as in the major world's fairs held in Paris (1867 & 1878) and Philadelphia (1876).

In his own words, Eugène Farcot explained the origins of his idea during the 1867 Paris universal exposition (translated from French):

Huygens suspended his conical pendulum from the rod itself, which gave it its rotation; an arrangement which has been advantageously employed as a regulator of steam machines, but which it is not possible to introduce in horology where, the latter has no more than a little force. Perhaps some wheels and pinions more than this clock needs have stopped the clockmakers of the period when dentures were still made by hand. It was almost forgotten in our days.Mr. Foucault, by his experiment in the Panthéon, etc., brought it to mind, and it is to Mr. Balliman that we truly owe the first successful application to clocks. He exhibited a type in the show of 1855; a type which, as with all novelty, was joked about even by those who later appropiated the idea.

Afterwards, Mr. Redier came to the Besançon exposition, in 1860, with a conical pendulum regulator with horizontal motion, and he published a memoir on this topic in the same year.

These diverse works made me conceive the idea of applying the pendulum in question to decorative clockmaking, that is to say, the statues hold in their hand the pendulum whose silent opperation and decorative effect should be suitable for bedrooms, salons, etc.

There remained its implementation, because it had to be created: caliber, suspension, fast-slow control, driving fork, etc. In 1862, I took to London the first specimens of its kind that took place in our industry since I first marketed it commercially.[2]

Each mystery clock of this one-of-a-kind series was individually made and therefore, no two are alike. They are distinguished for their artistic/horological excellence where foremost, award-winning people from various arts, crafts and sciences, created a masterpiece of Second Empire decorative arts.

Besides a remarkable precision in timekeeping, one of their most distinctive characteristics is the slow continual circular motion at a constant speed (instead of the conventional side to side swinging motion) of the noiseless pendulum, tracing a conical trajectory in space, hence its name.

List of the units

It is unknown the total number of units crafted, so far 12 have been found. It is unclear if the company used a separate serial number for its large-scale conical pendulum clocks, nevertheless taking into account they were extremely expensive, probably no more than twenty were ever made. Most of them are located in the United States:

|

|

Gallery on the monumental conical pendulum clocks

-

SN#23, exhibited at the London 1862 International Exhibition.

-

SN#8, exhibited at the Paris International Exposition (1867).

-

SN#16, exhibited at the Paris International Exposition (1867).

Literary works

- La navigation atmosphérique, 1859.

- Un voyage aérien dans cinquante ans, unpublished, 1864.

- Voyage du ballon le Louis-Blanc, 1874.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eugène Farcot. |

- Watch-wiki (German)

- Adrian Alan description

- Musée Farcot

- Bulletin des lois de l'Empire français, Volume 15, page 345. 1860.

- Bulletin des lois de la République Française, Volume 28, page 376. 1867.

External links

- Article on the monumental conical pendulum clocks by E. Farcot, pp. 75-93

- Video playlist about the large conical pendulum clocks

- Works by or about Eugène Farcot at Internet Archive

- ↑ Charles Gallaud, “Première Visite à l’Exposition des Arts Appliqués. Suivi des Considérations générales. – M. Farcot.”, La Célébrité, 6eannée, No. 38, (27/09/1863): 302.

- ↑ Claudius Saunier, “Exposition universelle de l’industrie en 1867”, Revue chronométrique (1867): 186-187.

- ↑ Charles Terwilliger,"John C. Briggs and Rotary Pendulum Clocks", NAWCC Bulletin, No. 193 (April 1978): 112.

- ↑ Arnold Lewis, James Turner and Steven McQuillin, The Opulent Interiors of the Gilded Age (1987): 176