Forests of the Iberian Peninsula

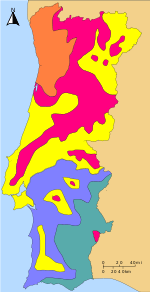

The woodlands of the Iberian Peninsula are distinct ecosystems on the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). Although the various regions are each characterized by distinct vegetation, the borders between these regions are not clearly defined, and there are some similarities across the peninsula.

Origin and characteristics

The flora of the peninsula, because of bio-historical, geographical, geological, and orographic conditions, is among of the richest and most varied of all European floras, rivaled only by such countries as Greece and Italy; it is estimated that the Iberian Peninsula has more than 8,000 distinct species of plants, many of them endemic.

It is now known that the Mediterranean Sea went through great changes in sea level and variations in the relative positions of the continental plates of Europe and Africa. These brought changes of climate and vegetation.

The Iberian Peninsula, located on an important route between Africa and Europe, was enriched by the arrival, following the climate change, of wetland plants, thermophilic plants (those that require a great deal of heat), xerophilic plants (those that require a dry climate), orophilic (sub-alpine) plants, Boreo-alpine plants, and so on, many of which managed to remain, thanks to the diversity of environments that exist in the mountain ranges, and which allowed them to rise in altitude if the climate was too warm, or descend if it became too cold. The geological complexity of the majority of Iberian mountains, especially of the Cordillera Bética, Sistema Ibérico, and Pyrenees, also greatly increased the number of new environments to which it was possible to adapt, resulting in today's wide variety of flora.

The Eurosiberian region

The "Eurosiberian" Atlantic zone extends through northern Portugal, the Galician Massif, Cantabrian Mountains and the western and central Pyrenees. It is characterized by a humid climate which is moderated by the influence of the ocean, with somewhat cold winters and the lack of a distinct dry season. The mainland extends to the north of Portugal, the greater part of Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque Country, northwest of Navarre, and western Pyrenees. However, its influence in the form of communities or defined species extends inwards, especially in the north and west.

The vegetation is deciduous oak forest: both sessile oaks (Quercus petraea)[1] and English oaks (Quercus robur), with European ash (Fraxinus excelsior) and hazels in the coolest and deepest soil at the bottom of the valley. The mountain layer is characterised by the presence of beeches and at times, in the Pyrenees, by silver firs (Abies alba); these beeches and silver firs occupy the cool slopes with shallow soil. The Mediterranean influence is felt in the presence of Holm oaks (Quercus ilex) with bay laurel, which are situated on the warmest crests and slopes, especially above chalky soil, where the dryness becomes more pronounced.

Improvement by humans has transformed much of this woodland into meadows, which conserve at their edges remnant hedgerows, "setos", of the species of the primitive forest. Clumps of thorny shrubs grow also in glades and clearings, such as the wild rose, blackberry bushes, blackthorn, hawthorn and other more or less thorny shrubs; this role can also be filled by smaller thorny plants, los piornales, and clumps of broom.

The major forests in this area are beech, oak, birch, and fir.

Beech forests

Beech forests (Fagus sylvatica) are found in the mountain layer of the Iberian Eurosiberian region from 800 to 1500 metres up. The soil is cool, as often chalky as siliceous (rich in silica), and nearly always acidified by rain. The layer is characterised by the beech tree. The beech tree projects a deep shadow, and so its dense foliage usually excludes other woodland species. It therefore has little undergrowth.

In spite of their Atlantic character, these forests reach Moncayo, in the centre of the peninsula. The southernmost are at the Hayedo de Montejo (in the autonomous community of Madrid) and in the northernmost area of the province of Guadalajara, in the Parque Natural del Hayedo de Tejera Negra (Cantalojas), and Somosierra-Ayllón. The forests seek watercourses and shade, and so their reforestation is very difficult and they are being displaced by the Pyrenean Oak (Quercus pyrenaica). The Irati "rainforest", of some 170 square kilometres in the Navarran Pyrenees, is one of the most important beech and fir forests in Europe.

Oak forests

Oak forests, above all of English oak (Quercus robur), are the most common in the Atlantic zone. They represent the typical forest floor formation of basal trees, extending to an altitude of some 600 metres. In higher regions, as one ascends the mountains, they yield to beech forests; at the bottom of the valleys they are replaced by ash trees and hazel tree groves. There are two main types of oak: the English oak and the sessile oak (Quercus petraea). The latter extends furthest into the interior and highest in altitude, but plays a secondary part; in general, when the climate begins to show its continental character, these oak forests are replaced by Pyrenean oak.

The land on which these oaks stood is the most altered, as it is well suited to meadows and crops. Oaks are often accompanied by chestnut trees and birches. When these forests degrade, they are taken over by thorny plants, piornales, and in the final extreme heather and gorse. The English oak would have been indigenous to a large part of the area currently occupied by pine forests and eucalyptus.

Birch forests

Along the Atlantic coast, birches (Betula species) form small enclaves or copses at the foot of rocky cliff edges or in the clearings of beech forests, on poor or acidic soils, accompanied by aspen (Populus tremula) and mountain ash (Sorbus aucuparia). Birch may also grow in pure stands near the beech forests, in the mountainous areas on siliceous bedrock; these areas are typically of only small extent and generally quite patchy with sessile oak (Quercus petraea) and trees of the genus Sorbus.

Fir forests

The silver fir (Abies alba) is found on the cool, deep-soiled slopes of the flanks of the Pyrenees, from Navarre to Montseny, forming pure fir woods or, more often, mixed forests with beech trees. The most important areas are in Lleida (Lérida), with 170 square kilometres. In altitude, it extends from 700 to 1700 meters, but its main areas are localized in more humid and dark valleys; these forests are dark, with acidic soil, due to the decomposition of the needles of evergreens. At higher altitudes, they are often replaced by black pine (Pinus uncinata). These spruce forests sometimes contain maples (Acer pseudoplatanus)[2] and their undergrowth is very similar to that of the beech forest. Like these, they are distinctly Euro-Iberian.

The Mediterranean region

The Mediterranean region occupies the rest of the peninsula (the greater part of it), as well as the Balearic Islands. The principal characteristic of the region is the existence of a quite lengthy period of summer drought, which may last anywhere from 2 to 4 months, but which, regardless of length, is always quite distinct. Rainfall can range from 1500 mm to less than 350 mm. Temperatures range from regions that have no frost for many years to those that reach -20 °C, or even lower, every winter.

If one ignores, for the moment, the influence of the mountains, the typical Mediterranean peninsular forest is made up of evergreen trees: oak forests, cork oaks, wild olives, juniper, and so on. These are accompanied or replaced in the warmer regions and eroded by forests of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) and in areas of sandy ground and fixed sand dunes by juniper and stone pine forests. Exceptions to the rule are the more arid region in the southeast, the lower regions of the provinces of Murcia and Almeria, where the only vegetation is the European fan palm (Chamaerops humilis), and thorny thickets of blackthorn and at higher altitudes, Kermes oak groves and mastic (Pistacia lentiscus). The same can be said of the salty or endorheic zones, with great differences in temperature, such as the depression of the Ebro, Hoya de Baza and the chalky marls further inland.

Pyrenean Oaks

Of all the oaks, the Pyrenean oak (Quercus pyrenaica) is the most resistant to drought and the continental-style climate. These forests, of a sub-Atlantic character, often represent the shift from Mediterranean vegetation to Atlantic vegetation. They cover a wide area of the peninsula and are of great importance, above all on the mountain ranges in the centre of the peninsula; from the interior of Galicia and extending south of the Cordillera Cantábrica they extend throughout the Sistema Central, reaching, to the south, (though scarce by the time they reach this region) the Sierra Nevada and Cádiz. They usually extend from some 700 to 800 metres to some 1500 to 1600 m in altitude. They prefer siliceous soil and, as altitude increases, they replace the damp oak forests and cork oak; on the high ground they give way to Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) forests or to los piornales serranos with creeping juniper. In areas where the influence of the Atlantic is more evident, they are taken over by heather and Erica australis; in the remainder, in clearings and in more degraded phases, rock rose (Cistaceae) mixed with laurel leaf and Spanish lavender (Lavandula stoechas) is more frequent. Their natural range is usually covered by forests of Scots pine or maritime pine.

Groves, riparian forests, and valley floors

In the groves, riparian forests, and valley floors, there are enclaves of deciduous forests that favor for the moist ground, which is constant almost all year; this allows them to avoid the consequences of the summer drought so characteristic of a Mediterranean climate.

There we see a characteristic pattern, as we move outward from the edge of the riverbed, so that the woodlands that are most dependent on the aquifer are on the riverbank, that is, (alders and willow groves) and those less dependent on water are located further away, such as the (ash, elm, and poplar groves).

These woodlands are formed by willows, poplars, alder, ash, elm and sometimes by Pyrenean oak (Quercus pyrenaica), lime trees, birches and hazel trees. When the humidity starts to diminish in barren areas of the Ebro valley, the Levante and the southern half of the peninsula, the dryness is often accompanied by an increase of salts in the ground; under such conditions one can find formations of tamarisk shrubs, oleanders and giant reeds (Saccharum ravenae), sometimes accompanied by heather. In soils rich in silica but not in salts, such as those of the Sierra Morena and the Montes de Toledo, spurge appears, accompanied, in the warmest places, by oleanders and tamarisks.

In the lowlands further inland, above all in the marls and clay soils, field elms (Ulmus minor) and poplar groves are more common, with occasional ashes and willows. At the bottom of granite valleys and on the siliceous riverbanks, there are very typical formations of ash with Pyrenean oak, especially at the foot of thin interior mountain ranges. The sheltered gorges of the Serranía de Cuenca have mixed riparian forests of lime and hazel trees, with ashes, willows and Wych elm (Ulmus glabra).

Because these woods occupied some of the most fertile lands, where people have planted orchards since ancient times, they have not been well preserved.

Spanish firs

The Spanish fir (Abies pinsapo) is a true relic which has remained preserved in some mountain ranges around Málaga and Cádiz. Spanish firs are related to the North African spruce forests of the Yebala range, in Morocco. They come into contact with Algerian oak (Quercus canariensis) and other oak trees and sometimes even form mixed communities with these. Among the woody species also found in these forests are the hawthorn, barberry, butcher's broom (Ruscus aculeatus), Viburnum tinus, ivy, and Daphne laureola.

It forms dense and dark forests in very distinct enclaves, in areas with high rainfall (from 2,000 to 3,000 mm, due to the sudden cooling, with elevation, of humid winds), at altitudes of over 1,000 metres. The forest has abundant moss and lichens, but very few shrubs and herbaceous plants. In all cases, Spanish fir occupies high mountain zones (such as the Sierra de las Nieves, Sierra Bermeja, and Sierra de Grazalema).

Holm oak forests

Forests of Holm oak (Quercus ilex) form natural forests in most of the Mediterranean region as well as penetrating into the warmer sun-exposed areas and hillsides of the Atlantic region; they extend from sea level, with the subspecies ilex, to an altitude of 1400 metres, in some mountains and high plains of the interior; in the continental zone, the oak found is the subspecies rotundifolia, more resistant to such a climate. The holm oak can also be found at higher altitudes, but as isolated trees, not forming forests. Coastal oak forests and those of sublittoral mountains are extraordinarily rich and varied, with a variety of shrubs and lianas; often accompanied by bramble, honeysuckle, ivy, Viburnum tinus, butcher's broom and, in the southwest of the peninsula, wild olive trees. The oak forests of the Balearic Islands are also rich, and incorporate characteristic species of the islands, such as the Balearic cyclamen (Cyclamen balearicum Willk.).

Towards the interior of the peninsula, these forests become progressively more scarce: as the continental characteristics of the climate become stronger, the species most sensitive to cold become steadily more scarce. The continental groves, on soils lacking lime (calcium oxide), tend to be rich in junipers (Juniperus oxycedrus) and are superseded at higher altitudes and on cooler slopes by Pyrenean Oaks. This phenomenon is apparent in the Sierra de Guadarrama: when the oak forests have been destroyed, the soil is so poor and the environmental conditions so unfavourable, that it leads to ragged thickets dominated by common rock rose, Spanish lavender and rosemary. On limy soils something similar takes place, above all at altitudes of over 900 metres, oaks are accompanied by Spanish juniper (Juniperus thurifera) and the scarcity of shrubs is such that the same Holm oak (Q. ilex subsp. rotundifolia or ballota) dominates almost entirely on its own the first phases of deterioration of the forest. The degradation caused by burning or felling leads to thickets of Scorpion's thorn (Genista scorpius), thyme and common lavender (Lavandula angustifolia).

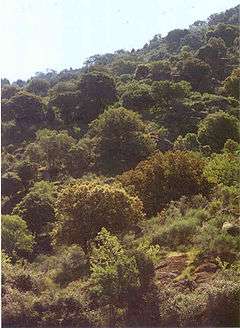

Cork oak forests

Cork oak forests occupy around 10,000 square kilometres on the peninsula, more than half of the world's extension of this kind of forest.

The cork oak forest needs siliceous soils of a sandy texture, and a mild, slightly damp climate. Under such conditions it totally or partially displaces the Holm oak; Holm oak may be found in stands of Cork Oak with a certain frequency, as well as Portuguese oaks (Quercus faginea subsp broteroi). The area occupied by oak forests corresponds above all to the southwest quadrant of the peninsula, but also to Catalonia, Menorca and even the non-coastal valleys of Galicia. They often alternate with the oaks, which occupy the drier slopes and with the quejigares of Algerian oak (Quercus canariensis), that occupy the ravines and cool, shady northward slopes.

The cork oak forests often contain wild olives, and like some of the cool groves, are often accompanied by strawberry trees (Arbutus unedo) with mock privet (Phillyrea angustifolia) which grow in the clearings of these forests and dominate their regressive phases. In western Andalusia, other common components of the ecosystem are the areas of common broom, genus Teline.

Quejigares

The term quejigar refers to forests of many different characteristics. Forests of Algerian oaks (Quercus canariensis) are well represented in western Andalusia and very patchily by hybridizations in Catalonia and the Cordillera Mariánica. They are the most demanding as to temperature and humidity, and therefore do not usually stray too far from areas with a maritime climate; they prefer the cooler, shady northward slopes, damp meadows and the banks of streams of the lower ground. In general, they alternate with the Cork Oaks, which they displace in the coolest zones; both prefer siliceous soils. In the clearings and degraded stages of these forests los piornos (Teline sp., Cytisus baeticus), heather (Erica arborea, Erica scoparia), and rock rose (Halimium lasianthum) are common.

Los quejigares of Portuguese oaks (Quercus faginea subsp faginea) are the most typical and common of the peninsula, since they are found from the Serranía de Ronda in Andalusia to the lower slopes of the Pyrenees. They are much more resistant to the cold and damp than Q. canariensis; on the other hand, they need cooler and deeper soils than the Holm oaks with which they come into contact. Although they can grow in any type of soil, in siliceous soils the usually play a secondary part with respect to Holm oaks, cork oaks, and Pyrenean oaks; it is only on chalky soils that it forms forests of any consideration, especially in the northeast quadrant and centre of the Peninsula. The natural area corresponding to the quejigo is frequently the black pine (Pinus nigra subsp salzmannii), which often has been extended at its expense.

Los quejigares can often include maples, serbales, European serviceberry or snowy mespilus (Amelanchier ovalis), common privet (Ligustrum vulgare L.) and common dogwood (Cornus sanguinea); their degradation can lead to extensive thickets of box.

The last quejigo, Quercus faginea subsp broteri requires the most moisture and is least resistant to cold. It is found principally in the southwest quadrant and prefers siliceous soils, somewhat cool. More frequently than in pure concentrations, it is found mixed with cork oaks and Holm oaks.

Pine forests

The most characteristic natural pine forests are those of pino negro (Pinus uncinata) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris). The former is often associated with ''Rhododendron ferrugineum, blueberries, Salix pyrenaica and other shrubby species on the subalpine slopes of the Pyrenees. Over less washed limestone soils it is usually accompanied by Savin juniper (Juniperus sabina L.), common juniper (Juniperus communis subsp. hemisphaerica), and common bearberry ([Arctostaphylos uva-ursi]). Such forests make up the tree line in most of the Pyrenees, reaching 2400 metres.

The Scots pine plays the same part in the other peninsular mountains, both siliceous and limy. It is accompanied and superseded at high altitude by piornales, dwarf junipers, and hummocky high mountain thickets. Their lower altitudinal limit remains patchy, having been extended at the expense of deciduous forests.

The maritime pine (Pinus pinaster) is found at an intermediate altitude and on generally siliceous soil, which in Galicia goes down to sea level and inland alternates with Pyrenean oak. Over limestone, the black pine (Pinus nigra subsp salzmannii)[3] plays an important role in many of the mountain ranges in the centre, east and south of the Peninsula; in limy soil, and at the same altitude, it usually displaces the former. Both are displaced at higher altitudes by the Scots pine.

The warmest of all the pine forests are those of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis), which are situated on rocky crests and sunny hillsides. Aleppo pine is the typical pine of the Mediterranean coast, from sea level to an altitude of 800–1000 metres in the interior; these prefer limy soils.

The stone pine (Pinus pinea), possibly the most characteristic of all, occupies sandy soils. It grows extensively both in the sandy areas of the lowlands in the provinces of Cádiz and Huelva, as well as points further inland (Valladolid, Cuenca, and Madrid). Finally, especial mention is necessary of the Monterey pine (Pinus radiata), because of its importance in reforestation and managed forests.

Juniper groves

The juniper groves of Spanish juniper (Juniperus thurifera) constitute a curious formation that occupies the high heaths and mesetas of the interior, nearly always above 900 metres in altitude. The principal woodlands of this type are in the Serranía de Cuenca, Sistema Ibérico, Alcarria, Maestrazgo and other mountains of the interior. They do not usually form dense forests, but rather parkland or small woods in meadows. They prefer soils developed over limestone, especially those of an ochre or reddish color and rich in clay, de carácter relicto (Terra rosa, Terra fusca); on occasions, as in the region of Tamajón (Guadalajara), they also colonize siliceous terrain.

They are adapted to an exceptionally harsh continental climate, where practically no other species of tree is a rival; except for the Holm oak, which occupies some of the old, deforested juniper groves, and the European black pine (Pinus nigra) which can accompany it with a certain frequency. The common juniper (Juniperus communis subsp. hemisphaerica) is habitually a secondary species of these groves. At high altitudes, they come in contact with forests of Scots pine and with the Savin juniper; the latter sometimes forming part of the shrubby stratum.

The fact that these are to be found mainly in areas which have been exposed for a large part of the Tertiary and over soils considered relictos, supposes a great antiquity for such groves. The harsh climatological conditions, with the surface of the ground undergoing processes of alternate freezing and thawing (cryoturbation), makes difficult the development of elevated brush. In their regressive stages, they tend toward hummocky thickets of cambrones (Genista pumila) or tomillares y prados de diente dominados por dwarf shrubs and dog's tooth grass. At lower altitudes, these groves can also alternate with espliego y aliaga.

The Phoenicean juniper (Juniperus phoenicea) habitually plays a secondary part and does not often form dense woods. Only on some rocky shelves or in special environments such as fixed dunes and sandy areas near the coast do they manage to form woodlands of any importance.

Thickets of the high Mediterranean mountains

The high Mediterranean mountains above 1700 metres presents some special characteristics. Winters are very harsh and long; the thickness of the snow and strong frosts prevent almost any type of biological activity. Once the snow has disappeared, the soil dries quickly due to the strong sun and high temperatures reached in summer. The period of time suitable for the growth of vegetation is therefore very short and for the above-mentioned reasons, the land is dry most of the time. Under such conditions, the forest enters a state of crisis, being replaced by piornales (ciste and broom formations) and thickets pluvinulares accompanied at lower levels by Scots pine, often isolated individuals twisted and deformed by the snow.

Siliceous mountains such as the Sistema Central, Serra da Estrela, the Sistema Ibérico of the region of Soria, and parts of the Cantabrian mountains, are covered by thickets of Cytisus purgans (variously known as "Andorra broom", "Provence broom", or "Spanish gold hardy broom") or Alpine juniper (Juniperus communis subsp. alpina). In the Sierra Nevada, on the other hand, under similar conditions, the Genista baetica,[4] is more dominant, sometimes accompanied by Cytisus purgans and another species of juniper (J. communis subsp. hemisphaerica).

In the limestone mountains such as the Maestrazgo and Serranía de Cuenca, a shrubby formation of Savin juniper (Juniperus sabina) accompanied by Scots pine is characteristic. In the limestone mountains of Andalusia a detectable role is played by thickets pluvilunares and hummocks of common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica).

Shrubby borders or undergrowths

From an ecological point of view, shrubby borders are fundamental in forest ecosystems to guarantee the natural regeneration of the woods, as well as to provide food and refuge for the associated fauna.

They are made up of spiny shrubs, depending on the forest and climate, such as gorse, box, thyme, and so on.

Stages of degradation

It is possible to identify successive stages in the process of degradation of these various forest formations, from an optimum state to the final phase of desertification.

These regressive states, in the case of leafy forests, are the following:

- Dense forest representative of an optimal natural state, characterized by endemic species, compatible with local biological conditions.

- Bosque aclarado, still with a predominance of the native species, but with abundant representation of a variety of species such as holly, maple, and ash. Frequently, leguminous plants predominate in the scrub of the underbrush.

- Stage of pine forests. The native species have practically disappeared, as has the associated vegetation. Together with the pines, heliophilic (preferring dry and sunny habitats) and invasive brush start to appear, almost always based on the families Cistaceae and Ericaceae.

- The stratum of trees as such disappears, along with its associated species, replaced progressively by brush representative of a very advanced degradation; there is a high frequency of thorny plants (Scorpion's thorn, blackthorn (Prunus spinosa), etc.) and a predominance of Lamiaceae y compuestas (Tomillo vulgar, heather, pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium), etc.).

- The ground cover is reduced, not only in the size of plants, but also in the area it occupies; now it forms a hebaceous and discontinuous tapestry, with a general predominance of dog's tooth grass. Woody plants are reduced to some thickets, the bedrock being exposed as a consequence of erosion. This is the typical landscape of the steppe.

- The final stage of regression is represented by desertified ground.

Notes

- ↑ CSIC List of Iberian flora Quercus sp. (Spanish)

- ↑ Flora digital de Portugal Acer pseudoplatanus (Portuguese)

- ↑ CSIC List of Iberian flora Pinus sp. (Spanish)

- ↑ CSIC List of Iberian flora Genista sp. (Spanish)

References and bibliography

- Blanco, Emilio (1998). Los bosques españoles (in Spanish). Barcelona: Lunwerg. ISBN 84-7782-496-7.

- Ferreras, Casildo y Arozena, María Eugenia (1987). Geografía Física de España: Los bosques (in Spanish). Barcelona: Alianza Editorial.

- Ortuño, Francisco; Ceballos, Andrés (1977). Los bosques españoles (in Spanish). Madrid: Incafo. ISBN 84-400-3690-6.

- Rivas-Martínez, S. (1987). Memoria del mapa de series de vegetación de España 1:400.000. (in Spanish). Madrid: ICONA. Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. ISBN 84-85496-25-6.

External links

- (English) Iberian nature portal - English-language portal on Iberian nature

- (Spanish) Atlas Forestal de Castilla y León

- (Spanish) Bosques del área atlántica

- (Spanish) S. Riera Mora, Cambios vegetales holocenos en la región mediterránea de la Península Ibérica (pdf)

- (Spanish) Los alcornocales on WWF/Adena (pdf).

- (Spanish) Jose Lietor Gallego, Patrones de disponilidad de nutrientes en masas de pinsapar (pdf). Doctoral thesis. Rev. Ecosistemas.