Eve Drewelowe

Eve Drewelowe (1899–1988) was an American painter. Her career spanned six decades and produced more than 1,000 works of art in oil, watercolor, pen and ink and other media in styles that included impressionism, social realism and abstraction.

Eve Drewelowe was born in New Hampton, Iowa on April 15, 1899 to George Drewelow and Mary Marguerita Martin. The eighth child of twelve, she grew up on a farm with a tomboyish spirit. Her father died when Eve was just 11 years old. She did not take art classes in her youth due to her farm duties, but she later came to appreciate this. She believed a formal artistic education would have hindered her development of a unique artistic style.[1] She graduated from New Hampton High School in 1919.[2] She attended the University of Iowa School of Art and Art History, receiving a bachelor's degree in graphic and plastic arts in 1923. Working closely with her father figure and mentor Carl Seashore, she encouraged the university to establish a graduate program in the arts. In 1924 she became the first student to earn a master's degree in studio arts from the university, and one of the first in the nation.[3]

Throughout her undergraduate and graduate school educations, Drewelowe experimented with impressionism. Art professor Charles A. Cumming discouraged any influences on her work outside of classwork. She was educated with little emphasis on contemporary art. Regardless, she showed interest in Cubism and other forms of abstract art.[4]

Despite warnings from Cumming that marriage could be fatal to her career, Eve married a fellow University of Iowa graduate and political scientist Jacob Van Ek in 1923.[4] Shortly after, the couple moved to Boulder, Colorado where he taught and became dean at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Drewelowe became a founding member and president of the Boulder Arts Guild in the city.[5] She taught part-time at the University of Colorado, Boulder in 1927-1928 and in the Department of Fine Arts in 1936-1937 for two summer sessions.[6]

Drewelowe's father George Drewelow, a farmer and environmentalist, was a large influence on her work. This and her love of Western landscapes had a strong impact on the subject matter of work.[6] In the early years of her artistic career, Eve painted landscapes almost exclusively. She especially favored the views in Colorado, featured in works such as Pine and Peak, Aspen, Colorado.[7] Although some paintings feature figures and most others simply a landscape, all of the paintings from this period in her life are painted within the spectrum of social realism.[8] Eve traveled with her husband Jacob to 23 countries in a span of 13 months. She filled seven sketchbooks with the inspirational sights she encountered. She produced many vivid landscape paintings based on her travels.[9][10] She produced Telling Trails, a series of ink drawings documenting her trip. This is the first documented incidence of what would become characteristic for Eve in this time—“flowing, undulating lines and unusual perspectives.”[8]

George Drewelow contributed not only to Eve’s artistic style but also to her personal ideals. She often voiced her concerns about increasing human interloping in the natural world as more and more land is converted to developments for the use of humans. She believed in conservation of food, water, resources, and other materials.[8] She felt that humans polluted the allure of the earth, both literally and figuratively by dulling its vivid beauty.[10] Her paintings depict colorful and fantastic landscapes, as if she is imagining how the world would look untouched by humans. However, she stayed well within the realm of realism at this point in her life.

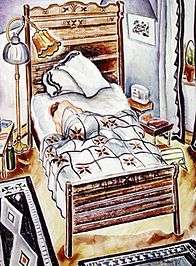

In 1940, Drewelowe became gravely ill. She underwent surgery at Mayo Clinic in New York for the removal of a gastric polyp. This procedure was very dangerous at the time. She depicted her painful hospital stays in Self-Portrait (Reincarnation) (1939). In this painting, her body is twisted and clearly in pain, but the colors used are reassuring. The surgery was successful, and this near-death experience gave Drewelowe’s artwork a new direction.[8] She began to integrate abstract elements into her paintings and transition her works more into abstraction. Her first entirely abstract painting was Crescendo in 1949. By 1959 her paintings became unrecognizable as landscapes. During her period of “reincarnation,” the colors she used in her painting became bright and vivid. She especially enjoyed working with circles, a theme that appeared often in this period of her art. She began to integrate new materials into her art, such as wood splinters or metal. The canvases she used also grew larger.[8] Everything about her art became more assertive and bold.

Despite dabbling with other artistic styles, Drewelowe always showed an inclination toward landscapes. She returned to painting landscapes in the 1980s as she did in the 1920s-30s. In these landscapes from the 1980s she depicted more of a human presence on the land.[4] She was becoming elderly but always wanted to keep painting.[11] She once said, “my waking thought from an embryo on was my need to be an artist.”[9] Maverick (1984) is thought to be one of Drewelowe’s last paintings.[8] It is a self-portrait utilizing a blend of realism and abstraction. It is as though Drewelowe is culminating her artistic life with a reflection of all of the stages of her life.[4]

Though never known to have used the word to describe herself, Eve Drewelowe is often considered a feminist artist. Her personal life exhibited feminist themes: the artist retained her maiden name and publicly stated a disinterest in housework and parenting. Drewelowe chose not to take her husband’s last name because in her opinion it should not matter to others whether she is married or not. When Drewelowe and Van Ek returned from their travels and started building a house together, Eve herself constructed much of the furniture and sewed decorations for the home.[9] She did not want to be involved in the pleasantries of being the dean’s wife, especially hosting dinner parties, so she specified to have the house built lacking a dining room.[11] She always maintained that she did not want to have children of her own, much to her mother’s dismay.[12]

Drewelowe struggled with which surname to use for herself. She exhibited under the name Eve Drewelowe Van Ek until the early 1950s, when she resumed using her maiden name. Even after this point, it can be seen on some of her paintings that she painted Van Ek and then rubbed it out. However, she never wanted to be called Mrs. Van Ek or even Mrs. Drewelowe.[4] In fact, her Daily Camera file in Boulder, Colorado contains a note from Drewelowe stating that “she intends to come back and haunt anyone who refers to her as Mrs. Van Ek in her obituary.”[9]

Although Drewelowe is mainly renowned in Colorado and Iowa, she had solo exhibitions all over the country. Her work was shown at National Association of Women Artists exhibitions, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Denver Art Museum, the National Museum of Women in the Arts and numerous other esteemed institutions.[10] Although women had been in the profession of art for 20–30 years at the beginning of Drewelowe’s career, she still faced opposition and sexism. Critics believe that she could have been much more acclaimed had she not been a woman and had she not fallen ill at the peak of her career. Others believe that her “reincarnation” and transition to abstract paintings increased Drewelowe’s popularity as an artist by keeping her relevant in an evolving artistic world.[4]

Eve Drewelowe died in Boulder, Colorado, on October 22, 1988. She opted to donate her collection of personal papers and artworks to the University of Iowa School of Art and Art History. She made it known that she donated her body to aid scientific research.[9] Undergraduate scholarships in art are named in her honor at both the University of Colorado and the University of Iowa. In 1979 she was named as a University of Iowa Distinguished Alumni. The Eve Drewelowe Gallery in the University of Iowa's Studio Arts Building is named for her.[3] Her Daily Camera file can be found in the Carnegie Branch library of Boulder, Colorado.[9]

Notes

- ↑ Carnes, Jan. Biographical Diary. N.d. MS 4, Eve Drewelowe. Iowa Women's Archives, n.p.

- ↑ "Guide to the Eve Drewelowe papers". The University of Iowa Libraries. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- 1 2 "Distinguished Alumni Awards". Eve Drewelowe, 23BA, 24MA. The University of Iowa Alumni Association. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shannon, Lindsay E. "Drewelowe: Feminist Identity in American Art." Women's History Review 22.2 (2013): 295-309. Taylor and Francis Group. Atypon Literatum, 21 Jan. 2013. Web. 16 Oct. 2015.

- ↑ Peter Hastings Falk, ed. (1999). Who Was Who in American Art 1564-1975. Madison, CT: Sound View Press. p. 962. ISBN 0-932087-55-8.

- 1 2 Phil Kovinick and Marian Yoshiki-Kovinick (1998). An Encyclopedia of Women Artists of the American West. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, Austin. p. 79. ISBN 0-292-79063-5.

- ↑ "Artist Biography for Eve Drewelowe." AskART. AskART, n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Benetti, Melvyn. "Eve Drewelowe: The Transition of a Social Realist to an Abstract Painter." Thesis. Iowa Women's Archives, 1989. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Taylor, Carol. "Boulder History: Eve Drewelowe, Modernist and Feminist." Boulder Daily Camera. Digital First Media, 30 June 2012. Web. 16 Oct. 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Eve Van Ek Drewelowe." David Cook Galleries. David Cook Galleries, n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2015.

- 1 2 "Boulder Artist, 87, Focuses on Present." Rocky Mountain News [Denver, CO] Mar. 1987, Entertainment sec.: n. pag. Print.

- ↑ Drewelowe, Eve. Autobiographical Draft. N.d. MS 1, Eve Drewelowe. Iowa Women's Archives, n.p.

External links

- Eve Drewelowe Digital Collection at The University of Iowa Libraries

- Eve Drewelowe at AskART