Hexi Corridor

Hexi Corridor (Chinese: 河西走廊; pinyin: Héxī Zǒuláng; Wade–Giles: Ho2-hsi1 Tsou3-lang2, Xiao'erjing: حْسِ ظِوْلاْ, IPA: /xɤ˧˥ɕi˥ tsoʊ˨˩˦lɑŋ˧˥/) or Gansu Corridor refers to the historical route in Gansu province of China. As part of the Northern Silk Road running northwest from the bank of the Yellow River, it was the most important route from North China to the Tarim Basin and Central Asia for traders and the military. The corridor is a string of oases along the northern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. To the south is the high and desolate Tibetan Plateau and to the north, the Gobi Desert and the grasslands of Outer Mongolia. At the west end the route splits in three, going either north of the Tian Shan or south on either side of the Tarim Basin. At the east end are mountains around Lanzhou before one reaches the Wei River valley and China proper.

History

Early crop dispersal

Cultivated wheat, originating at the Fertile Crescent, already appeared in China around 2800 BC at Donghuishan at the Hexi corridor. Several other crops are also attested at this time period. Xishanping is another similar site in Gansu.[1]

According to Dodson et al. (2013), wheat entered via the Hexi Corridor into northern Gangsu around 3000 BC, although other scholars date this somewhat later.[2]

The Chinese millets (Panicum miliaceum, and Setaria italica), rice, as well as other crops travelled the opposite way through the Corridor, and reached western Asia and Europe from the fifth millennium to the second millennium BC.[2]

As early as the 1st millennium BCE, silk goods began appearing in Siberia, having traveled over the Northern branch of the Silk Road, including the Hexi Corridor segment.[3]

Qin dynasty

At the end of the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE), the Yuezhi overcame previous settlers, the Wusun and Qiang, occupying the western Hexi Corridor. Later, Northern Xiongnu armies vanquished the Yuezhi and established dominance here during the early Han dynasty.[4]

Han Dynasty

During the Han–Xiongnu War, Han China expelled the Xiongnu from the Hexi Corridor in 121 BCE and even drove them from Lop Nur when King Hunye surrendered to Huo Qubing in 121 BCE. The Han acquired a territory stretching from the Hexi Corridor to Lop Nur, thus cutting the Xiongnu off from their Qiang allies. Again, Han forces repelled a joint Xiongnu-Qiang invasion of this northwestern territory in 111 BCE. After 111 BCE, new outposts were established, four of them in the Hexi Corridor, namely Jiuquan, Zhangye, Dunhuang, and Guzang (Wuwei).

From roughly 115–60 BCE, Han forces fought the Xiongnu over control of the oasis city-states in the Tarim Basin. Han was eventually victorious and established the Protectorate of the Western Regions in 60 BCE, which dealt with the region's defense and foreign affairs.

During the turbulent reign of Wang Mang, Han lost control over the Tarim Basin, which was conquered by the Xiongnu in 63 CE, and used as a base to invade the Hexi Corridor. Dou Gu defeated the Xiongnu again at the Battle of Yiwulu in 73 CE, evicting them from Turpan and chasing them as far as Lake Barkol before establishing a garrison at Hami.

After the new Protector General of the Western Regions Chen Mu was killed in 75 CE by allies of the Xiongnu in Karasahr and Kucha, the garrison at Hami was withdrawn. At the Battle of the Altai Mountains in 89 CE, Dou Xian defeated the Northern Chanyu, who retreated into the Altai Mountains.

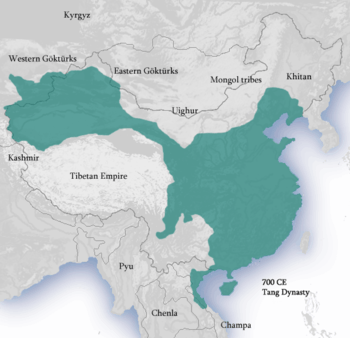

Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty fought the Tibetan Empire for control of areas in Inner and Central Asia. There was a long string of conflicts with Tibet over territories in the Tarim Basin between 670–692 CE.

In 763 the Tibetans even captured the Tang capital of Chang'an for fifteen days during the An Lushan Rebellion. It was during this rebellion that the Tang withdrew its western garrisons stationed in what is now Gansu and Qinghai, which the Tibetans then occupied along with the area that is modern Xinjiang. Hostilities between the Tang and Tibet continued until they signed a formal peace treaty in 821. The terms of this treaty, including fixed borders between the two countries, are recorded in a bilingual inscription on a stone pillar outside the Jokhang in Lhasa.

Western Xia Dynasty

The Western Xia Dynasty, known also as the Tangut Empire, was established in the 11th century by Tangut tribes. Western Xia controlled from 1038 CE up to 1227 CE the areas in what are now the northwestern Chinese provinces of Gansu, Shaanxi, and Ningxia.

Yuan Dynasty

Genghis Khan began the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty around 1207 and Ögedei Khan continued it after his death in 1227. The Jin dynasty of the Jurchen people fell in 1234 CE with help from the Han Chinese dynasty of the Southern Song.

Ögedei also crushed the Western Xia in 1227, pacifying the Hexi Corridor region, which was later controlled by the Yuan dynasty established by Kublai Khan, the fifth Khagan of the Mongol Empire. The Yuan lasted officially from 1271-1368.

Geography and climate

The Hexi Corridor is a long, narrow passage stretching for some 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from the steep Wushaolin hillside near the modern city of Lanzhou to the Jade Gate[5] at the border of Gansu and Xinjiang. There are many fertile oases along the path, watered by rivers flowing from the Qilian Mountains, such as the Shiyang, Jinchuan, Ejin (Heihe), and Shule Rivers.

A strikingly inhospitable environment surrounds this chain of oases: the snow-capped Qilian Mountains ("Nanshan") to the south; the Beishan mountainous area, the Alashan Plateau, and the vast expanse of the Gobi desert to the north. Geologically, the Hexi Corridor belongs to a Cenozoic foreland basin system on the northeast margin of the Tibetan Plateau.[6]

The ancient trackway formerly passed through Haidong, Xining and the environs of Juyan Lake, serving an effective area of about 215,000 km2 (83,000 sq mi). It was an area where mountain and desert limited caravan traffic to a narrow trackway, where relatively small fortifications could control passing traffic.[7]

There are several major cities along the Hexi Corridor. In western Gansu Province is Dunhuang (Shazhou), then Yumen, then Jiayuguan, then Jiuquan (Suzhou), then Zhangye (Ganzhou) in the center, then Jinchang, then Wuwei (Liangzhou) and finally Lanzhou in the southeast. In the past, Dunhuang was part of the area known as the Western Regions. South of Gansu Province, in the middle just over the provincial boundary, lies the city of Xining, the capital of Qinghai Province. Xining was the chief commercial hub of the Hexi Corridor.

The Jiyaguyan fort guards the western entrance to China. It's located in Jiayuguan pass at the narrowest point of the Hexi Corridor, some 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) southwest of the city of Jiayuguan. The Jiyaguyan fort is the first fortification of Great Wall of China in the west.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Li, Xiaoqiang; et al. (2007a). "Early cultivated wheat and broadening of agriculture in Neolithic China" (PDF). The Holocene (journal). 17 (5).

- 1 2 Stevens, C. J.; Murphy, C.; Roberts, R.; Lucas, L.; Silva, F.; Fuller, D. Q. (2016). "Between China and South Asia: A Middle Asian corridor of crop dispersal and agricultural innovation in the Bronze Age" (PDF). The Holocene. 26 (10): 1541–1555. doi:10.1177/0959683616650268. ISSN 0959-6836.

- ↑ Silk Road, North China, C.Michael Hogan, the Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham

- ↑ "Dunhuang History". Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Zhihong Wang, Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage, 經典雜誌編著, 2006 ISBN 9868141982

- ↑ Youli Li; Jingchun Yang; Lihua Tan; Fengjun Duan (July 1999). "Impact of tectonics on alluvial landforms in the Hexi Corridor, Northwest China". Geomorphology. 28 (3–4): 299–308. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(98)00114-7.

- ↑ "The Silk Roads and Eurasian Geography". Retrieved 2007-08-06.

Sources

- Yap, Joseph P. (2009). "Wars With The Xiongnu - A Translation From Zizhi tongjian" . AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4490-0605-1