Assassination of James A. Garfield

| Assassination of James A. Garfield | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′31″N 77°01′13″W / 38.89194°N 77.02028°WCoordinates: 38°53′31″N 77°01′13″W / 38.89194°N 77.02028°W |

| Date |

July 2, 1881 9:30 am (Eastern Time) |

| Target | James A. Garfield |

Attack type | Assassination |

| Weapons | Bulldog Revolver |

| Deaths | 1 (Garfield) |

Non-fatal injuries | None |

| Perpetrator | Charles J. Guiteau |

| Motive | Retribution for perceived failure to reward campaign support |

The assassination of President James A. Garfield took place at 9:30 am on July 2, 1881, less than four months into Garfield's term as the 20th President of the United States. Garfield was shot by Charles J. Guiteau at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C. He died in Elberon, New Jersey eleven weeks later, on September 19, 1881. Garfield was the second of four Presidents to be assassinated, following Abraham Lincoln and preceding William McKinley and John F. Kennedy. His Vice President, Chester A. Arthur, succeeded Garfield as President.

Garfield survived the longest after being shot, compared with the other presidents who were assassinated. Lincoln died nine hours after being shot, McKinley survived for a week before dying, and Kennedy died almost instantly. Garfield's assassin also lived the longest after the event, executed almost a year following the shooting and nine months after Garfield's death. John Wilkes Booth was hunted down and killed eleven days after Lincoln's death, Leon Czolgosz was executed just over a month after killing McKinley, and Lee Harvey Oswald was shot and killed by Jack Ruby two days after assassinating Kennedy.

Assassination

Background

Charles Guiteau turned to politics after failing in several ventures, including theology, a law practice, bill collecting, and time in the utopian Oneida Community. He wrote a speech in support of Ulysses S. Grant called "Grant vs. Hancock." Grant was the early front runner for the Republican nomination for president in the election of 1880, but lost to Garfield. Guiteau then revised his speech to "Garfield vs. Hancock" and though he tried to sign on as a campaigner for the Republican ticket, he never delivered the speech in a public setting, instead printing and distributing several hundred copies.[3] Guiteau's speech, even in written form, was ineffective. Among other problems, his hurried effort to replace references to Grant with references to Garfield was incomplete. But Guiteau convinced himself that this speech was largely responsible for Garfield's narrow victory over Democratic nominee Winfield S. Hancock. Guiteau believed he should be awarded a diplomatic post for his supposedly vital assistance, first asking for a consulship in Vienna, then expressing a willingness to "settle" for one in Paris.[4] He loitered around Republican headquarters in New York City, expecting rewards for his speech, to no avail.[5]

Still believing he would be rewarded, Guiteau arrived in Washington on March 5, 1881, the day after Garfield's inauguration. He obtained entrance to the White House and saw the President on March 8, 1881, dropping off a copy of his speech as a reminder of the campaign work he had supposedly done on Garfield's behalf.[6] He spent the next two months roaming around Washington, staying at rooming houses and sneaking away without paying, shuffling back and forth between the State Department and the White House, and approaching various Cabinet members and other prominent Republicans and seeking support, all without success. Guiteau was destitute and increasingly slovenly because he was wearing the same clothes every day. On May 13, 1881, he was banned from the White House waiting room. On May 14, 1881 he encountered Secretary of State James G. Blaine, who told him to "Never speak to me again of the Paris consulship as long as you live."[7]

Guiteau's family had judged him to be insane in 1875 and attempted to have him committed, but Guiteau had escaped.[8] Now his mania took a violent turn. After the encounter with Blaine, Guiteau decided that he had been commanded by a higher power to kill the supposedly ungrateful president later stating, "I leave my justification to God."[9]

After borrowing $15 (equivalent to $368 in 2015) from George Maynard, a relative by marriage, Guiteau went out to purchase a revolver.[10] He knew little about firearms, but believed he would need a large caliber gun. While at O'Meara's store in Washington, he had the choice between two versions of the .442 Webley caliber British Bulldog revolver,[10] one with a wooden grip and another with an ivory grip; he chose the one with the ivory handle[11][12][13] because he thought it would look better as a museum exhibit after the assassination.[13] Though he could not afford the extra dollar, the store owner dropped the price for him.[14] (The revolver was recovered and displayed by the Smithsonian in the early 20th century, but has since been lost.)[15] He spent the next few weeks in target practice—the kick from the revolver almost knocked him over the first time[16]—and stalking Garfield. He wrote a letter to Garfield, saying that he should fire Blaine, or "you and the Republican party will come to grief."[17] The letter was ignored,[18] as was all the correspondence Guiteau sent to the White House.[19]

Guiteau continued to prepare carefully, writing a letter in advance to William Tecumseh Sherman, the Commanding General of the U.S. Army, asking for protection from the mob he assumed would gather after he killed the President,[20][21] and writing other letters justifying his action as necessary to heal dissension between the factions of the Republican Party.[22] He went to the District of Columbia jail, asking for a tour of the facility to see where he would be incarcerated (he was told to come back later).[23] Guiteau spent the whole month of June following Garfield around Washington. On one occasion, he trailed Garfield to the railway station as the President was seeing his wife off to a beach resort in Long Branch, New Jersey, but he decided to shoot him later, as Lucretia, Garfield's wife, was known to be in poor health and he did not want to upset her.[24][25]

The shooting

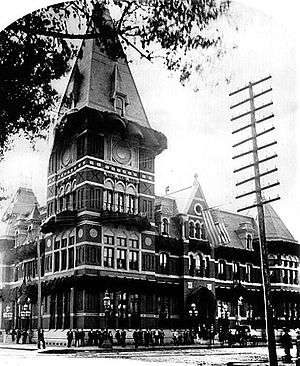

Garfield was scheduled to leave Washington on July 2, 1881, for his summer vacation, a fact which was reported in the Washington newspapers.[26] Reading of Garfield's plans, on that day, Guiteau lay in wait for President Garfield at the (since demolished) Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, on the southwest corner of present-day Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, D.C.[27]

President Garfield came to the Sixth Street Station on his way to his alma mater Williams College, where he was scheduled to deliver a speech. He was accompanied by two of his sons, James and Harry, and Secretary of State James G. Blaine. Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln waited at the station to see the President off.[25] Garfield had no bodyguard or security detail; with the exception of Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, early U.S. presidents did not employ guards.[24]

As Garfield entered the waiting room of the station, Guiteau stepped forward and pulled the trigger from behind at point-blank range. Garfield cried out, "My God, what is that?", flinging up his arms. Guiteau fired again and Garfield collapsed.[28] One bullet grazed the President's shoulder, and the other struck him in the back, passing the first lumbar vertebra but missing the spinal cord before coming to rest behind his pancreas.[29]

Guiteau put his pistol back in his pocket and turned to leave via a cab that he had waiting for him outside the station, but collided with policeman Patrick Kearney, who was entering the station after hearing the gunfire. Kearney apprehended Guiteau. He was so excited at having arrested the man who had presumably shot Garfield that he neglected to take Guiteau's gun from him until after their arrival at the police station.[30] Kearney demanded, "In God's name, what did you shoot the president for?" Guiteau did not respond. The rapidly gathering crowd screamed, "Lynch him!", but Kearney and several other police officers took the assassin to the police station a few blocks away.[28] As he surrendered to authorities, Guiteau uttered the exulting words, repeated everywhere: "'I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts! I did it and I want to be arrested! Arthur is President now!'"[31] This statement briefly led to unfounded suspicions that either Arthur or his supporters had put Guiteau up to the crime.[32] The Stalwarts were a Republican faction loyal to former President Grant; they strongly opposed Garfield's Half-Breeds.[33] Like many Vice Presidents, Chester A. Arthur had been selected as a running mate for political advantage—to placate his faction rather than for his skills or loyalty. Guiteau, in his delusion, had convinced himself that he was striking a blow to unite the two factions of the Republican Party.[34]

Treatment and death

Garfield, conscious but in shock, was carried to an upstairs floor of the train station.[35] One bullet remained lodged in his body, but doctors could not find it.[36] His son James Rudolph Garfield, and Secretary of State James Blaine, both broke down and wept. Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln, deeply upset and thinking back to the assassination of his father, said, "How many hours of sorrow I have passed in this town."[36]

Garfield was carried back to the White House. Although doctors told him that he would not survive the night, the President remained conscious and alert.[37] The next morning his vital signs were good and doctors began to hope for recovery.[38] A long vigil began, with Garfield's doctors, led by D. Willard Bliss, issuing regular bulletins that the American public followed closely throughout the summer of 1881.[39][40] His condition fluctuated. Fevers came and went. Garfield struggled to keep down solid food and spent most of the summer eating little, and then only liquids.[41]

In an effort to relieve the sick man from the heat of a Washington summer, Navy engineers rigged up an early version of the modern air conditioner. Fans blew air over a large box of ice and into the President's sickroom; the device worked well enough to lower the temperature twenty degrees.[42] Doctors continued to probe Garfield's wound with dirty, unsterilized fingers and instruments, attempting to find the location of the bullet.[43] Alexander Graham Bell devised a metal detector specifically for the purpose of finding the bullet lodged inside Garfield. He was unsuccessful, partly because Garfield's metal bed frame made the instrument malfunction, and partly because Bliss allowed Bell to use the device only on Garfield's right side, where Bliss insisted the bullet had lodged.[44] Bell's subsequent tests indicated that his metal detector was in good working order, and that he would have found the bullet had he been allowed to use the device on Garfield's left side.[45]

On July 29, Garfield met with his Cabinet for the only time during his illness; the members were under strict instruction from the doctors not to discuss anything upsetting.[46] Garfield became increasingly ill over a period of several weeks due to infection, which caused his heart to weaken. He remained bedridden in the White House with fevers and extreme pains. Garfield's weight dropped from over two hundred pounds (90.7 kilograms) to 135 pounds (61.2 kilograms) as his inability to keep down and digest food took its toll.[47] Because of his inability to digest food, nutrient enemas were given in an attempt to extend his life.[48] Blood poisoning and infection set in and for a brief period the President suffered from hallucinations.[49] Pus-filled abscesses spread all over Garfield's body as the infections raged.[50]

On September 6, Garfield was taken to the Jersey Shore to escape the Washington heat, in the vain hope that the fresh air and quiet there might aid his recovery.[49] Garfield was propped up in bed before a window with a view of the beach and ocean.[51] New infections set in, as well as spasms of angina. He died of a ruptured splenic artery aneurysm,[52] following blood poisoning and bronchial pneumonia, at 10:35 pm on Monday, September 19, 1881, in Elberon, New Jersey. Garfield died two months before his 50th birthday; he and John F. Kennedy are the only two Presidents who died before age 50. During the seventy-nine days between his shooting and death, Garfield's only official act was to sign a request for the extradition of a forger who had escaped, and was apprehended after he fled to Canada.[53]

Most historians and medical experts now believe that Garfield probably would have survived his wound had the doctors attending him been more capable.[54][55] Unfortunately for Garfield, most American doctors of the day did not believe in anti-sepsis measures or the need for cleanliness to prevent infection.[56] Several inserted their unsterilized fingers into the wound to probe for the bullet, and one doctor punctured Garfield's liver in doing so. Also, self-appointed chief physician D. Willard Bliss had supplanted Garfield's usual physician, Jedediah Hyde Baxter. Bliss and the other doctors who attended Garfield had guessed wrong about the path of the bullet in Garfield's body. They had erroneously probed rightward into Garfield's back instead of leftward, missing the location of the bullet but creating a new channel which filled with pus. The autopsy not only discovered this error but revealed pneumonia in both lungs and a body that was filled with pus due to uncontrolled septicemia.[57]

Chester Arthur was at his home in New York City when word came the night of September 19 that Garfield had died. After getting the news, Arthur said "I hope—my God, I do hope it is a mistake." But confirmation by telegram came soon after. Arthur was inaugurated early in the morning on September 20, and took the presidential oath of office from John R. Brady, a New York Supreme Court judge. Arthur then left for Long Branch to pay his respects to Mrs. Garfield before going on to Washington.[58]

Garfield's body was taken to Washington, where it lay in state for two days in the Capitol Rotunda before being taken to Cleveland, Ohio, where the funeral was held on September 26.[59]

Trial and execution

Guiteau went on trial in November.[60] Represented by his brother-in-law, George Scolville, Guiteau became something of a media darling during his trial for his bizarre behavior, including constantly insulting his defense team, formatting his testimony in epic poems which he recited at length, and soliciting legal advice from random spectators in the audience via passed notes. He claimed that he was not guilty because Garfield's murder was the will of God and he was only an instrument of God's will.[61] He sang "John Brown's Body" to the court.[62] He dictated an autobiography to the New York Herald, ending it with a personal ad for a nice Christian lady under thirty.[63] He was blissfully oblivious to the American public's outrage and hatred of him, even after he was almost assassinated twice himself. At one point, he argued that Garfield was killed not by him but by medical malpractice ("I deny the killing, if your honor please. We admit the shooting"), which was essentially true, if one discounts the fact that Guiteau was the reason the President required medical attention in the first place.[64] Throughout the trial and up until his execution, Guiteau was housed at St. Elizabeths Hospital in the southeastern quadrant of Washington, D.C.

Guiteau's trial was one of the first high-profile cases in the United States where the insanity defense was considered.[65] Guiteau vehemently insisted that while he had been legally insane at the time of the shooting, he was not really medically insane, which caused a major rift with his defense lawyers, and which probably contributed to the jury's impression that Guiteau was merely trying to deny responsibility.

To the end, Guiteau was actively making plans to start a lecture tour after his perceived imminent release and to run for president himself in 1884, while at the same time continuing to delight in the media circus surrounding his trial. He was dismayed when the jury was unconvinced of his divine inspiration, convicting him of the murder. He was found guilty on January 25, 1882.[66] He appealed, but his appeal was rejected, and he was hanged on June 30, 1882, in the District of Columbia. At his execution, Guiteau famously danced his way up to the gallows and while on the scaffold he waved at the audience, shook hands with his executioner and, as a last request, recited a poem he had written called "I am Going to the Lordy".[67] He requested an orchestra to play as he sang the poem; it was denied.

Aftermath

Part of Charles Guiteau's preserved brain is on display at the Mütter Museum at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.[68] Guiteau's bones and more of his brain, along with Garfield's backbone and a couple of ribs, are kept at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C., on the grounds of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center.[69]

Garfield's assassination was instrumental to the passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act on January 16, 1883. Garfield himself had called for civil service reform in his inaugural address[70] and supported it as President in the belief that it would make government more efficient.[71] It was passed as something of a memorial to the fallen President.[72] Arthur lost the Republican Party nomination in 1884 to Blaine, who went on to lose a close election to Democrat Grover Cleveland.

The Sixth Street rail station was later demolished. The site is now occupied by the West Building of the National Gallery of Art. No plaque or memorial marks the spot where Garfield was shot,[73] but a few blocks away, a Garfield memorial statue stands on the southwest corner of the Capitol grounds.

The question of Presidential disability was not addressed. Article II, section 1, clause 6 of the Constitution says that in case of the "Inability [of the President] to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the same shall devolve on the Vice President", but gives no further instruction on what constitutes inability or how the President's inability should be determined. Garfield had lain on his sickbed for 80 days without performing any of the duties of his office except for the signing of an extradition paper, but this did not prove to be a difficulty because in the 19th century the federal government effectively shut down for the summer regardless. During Garfield's ordeal, the Congress was not in session and there was little for a President to do. Blaine suggested the Cabinet declare Arthur acting President, but this option was rejected by all, including Arthur, who did not wish to be perceived as grasping for power.[47][74]

Congress did not deal with the problem of what to do if a President were alive but incapacitated as Garfield was. Nor did the Congress take up the question 38 years later, when Woodrow Wilson suffered a stroke that put him in a coma for days and left him partially paralyzed and blind in one eye for the last year and a half of his Presidency. It was not until the Twenty-fifth Amendment was ratified in 1967 that there was an official procedure for what to do if the president became incapacitated.

Lincoln's assassination had taken place roughly sixteen years before in the closing stages of the Civil War. On the other hand, Garfield's term was marked (for the most part) by peacetime, and a general complacency with respect to presidential security had developed by this time. Garfield, like many other presidents, often preferred to interact directly with the public and although some form of security was almost certainly in place, a comprehensive security detail had not been seriously considered by either Congress or the president up to that point. Remarkably, it would not be until the assassination of William McKinley some twenty years later that Congress would finally task the United States Secret Service (originally founded to prevent counterfeiting) with the responsibility of ensuring the president's personal safety.[75]

The Garfield Tea House, built by the citizens of Long Branch, New Jersey, with the railroad ties that had been laid down specifically to give Garfield's train access to their town, still stands today near the location where Garfield died.[76]

See also

- Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

- Assassination of William McKinley

- Assassination of John F. Kennedy

- List of United States presidential assassination attempts and plots

References

- ↑ Cheney, Lynne Vincent. "Mrs. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper" Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.. American Heritage Magazine. October 1975. Volume 26, Issue 6. URL retrieved on January 24, 2007.

- ↑ "The attack on the President's life". Library of Congress. URL retrieved on January 24, 2007.

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 587

- ↑ Peskin (1978), pp. 588–589

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 588

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 589

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 590

- ↑ Millard (2011), pp. 80–82

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 170

- 1 2 "Trial Transcript: Cross-Examination of Charles Guiteau". Law2.umkc.edu. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ↑ Alexander (1882), pp. 107–108

- ↑ Reyburn, Robert (March 24, 1894). "History of the Case of President Garfield". Journal of the American Medical Association. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association: 412.

- 1 2 Elman (1968), p. 166

- ↑ June (1999), p. 24

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 165

- ↑ "Garfield's Assassin". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Springfield, IL: Illinois State Historical Society. 70: 136. 1977. ISSN 0019-2287. OCLC 1588445.

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 168

- ↑ Taylor (2007), pp. 77–78

- ↑ Kittler (1965), p. 114

- ↑ Vowell (2005), pp. 164–165

- ↑ Original letter in Georgetown Univ. collection

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 592

- ↑ "A Great Nation in Grief" The New York Times, 3 July 1881.

- 1 2 Peskin (1978), p. 593

- 1 2 Vowell (2005), p. 160

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 581

- ↑ Conwell (1881), p. 349

- 1 2 Peskin (1978), p. 596

- ↑ Millard (2011), pp. 189, 312

- ↑ "Garfield II: A Lengthy Demise". History House. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ New York Herald, July 3rd, 1881

- ↑ Millard (2011), p. 230

- ↑ Millard (2011), p. 47

- ↑ Millard (2011), p. 178

- ↑ Peskin (1978), pp. 596–597

- 1 2 Peskin (1978), p. 597

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 598

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 599

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 600

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 124

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 601

- ↑ Peskin (1978), pp. 601–602

- ↑ Millard (2011), p. 194

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 602

- ↑ Millard (2011)

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 603

- 1 2 Peskin (1978), p. 604

- ↑ Bliss, D. W. "Feeding Per Rectum: As Illustrated in the Case of the Late President Garfield and Others". Washington: N.p., n.d. Rpt. from the Medical Record, July 15, 1882.

- 1 2 Peskin (1978), p. 605

- ↑ Millard (2011), pp. 289–291

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 606

- ↑ Millard (2011), p. 313

- ↑ Swaney, Homer H. (1881). Lives of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Washington, DC: TRufus H. Darby, Printer and Publisher. p. 95.

- ↑ A President Felled by an Assassin and 1880’s Medical Care New York Times, July 25, 2006.

- ↑ Millard (2011), p. 208

- ↑ Millard (2011), pp. 25–26

- ↑ Millard (2011), pp. 312–313

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 608

- ↑ Peskin (1978), pp. 608–609

- ↑ Millard (2011), p. 321

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 173

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 136

- ↑ Millard (2011), p. 250

- ↑ Millard (2011), p. 322

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 175

- ↑ "Guiteau Found Guilty," New York Times. January 26, 1882, p.1.

- ↑ "Last Words of Assassin Charles Guiteau". University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ Siera, J.J. "Come see Dead People at the Mutter Museum". Venue Magazine. Rowan University. Issue 41. Volume 2. URL retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ↑ Carlson, Peter. "Rest in Pieces". The Washington Post. January 24, 2006. Page C1. URL retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 540

- ↑ Peskin (1978), pp. 551–553

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p. 610

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 159

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 171

- ↑ President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy (1992). The Warren Commission Report. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 110. ISBN 0-312-08257-6.

The first congressional session after the assassination of McKinley gave more attention to legislation concerning attacks on the President than had any previous Congress but did not pass any measures for the protection of the President. Nevertheless, in 1902 the Secret Service, which was then the only Federal general investigative agency of any consequence, assumed full-time responsibility for the safety of the President.

- ↑ Vowell (2005), p. 185

Cited works

- Alexander, H. H. (1882). The Life of Guiteau and the Official History of the Most Exciting Case on Record: Being the Trial of Guiteau for Assassinating Pres. Garfield. Philadelphia, PA: National Publishing Company.

- Conwell, Russell H. (1881). The Life, Speeches, and Public Services of James A. Garfield, Twentieth President of the United States: Including an Account of his Assassination, Lingering Pain, Death and Burial. Portland, ME: George Stinson. OCLC 2087548.

- Elman, Robert (1968). Fired in Anger: The Personal Handguns of American Heroes and Villains. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday & Company.

- June, Dale L. (1999). Introduction to Executive Protection. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-8128-7.

- Kittler, Glenn D. (1965). Hail to the Chief!: The Inauguration Days of our Presidents. Philadelphia, PA: Chilton Books.

- Millard, Candice (2011). Destiny of the Republic. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53500-7.

- Peskin, Allan (1978). Garfield: A Biography. Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-210-2.

- Taylor, Troy (2007). Wicked Washington: Mysteries, Murder & Mayhem in America's Capital. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-302-1.

- Vowell, Sarah (2005). Assassination Vacation. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-6003-1.

External links

- History House's account of Guiteau's life and the assassination of Garfield, part 1, 2 and 3.

- James A. Garfield On Prospect of Being Assassinated: Original Letters and Manuscripts Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- New York Times article reprinting indictment

- New York Times article on shooting at time of shooting

- Garfield's murder and Guiteau's trial at the Crime Library

- Charles Guiteau Trial homepage at the University of Missouri–Kansas City

- Charles J. Guiteau collection at Georgetown University

- "American Experience | Insanity on Trial". PBS. Retrieved September 21, 2015.