George Borrow

| George Henry Borrow | |

|---|---|

|

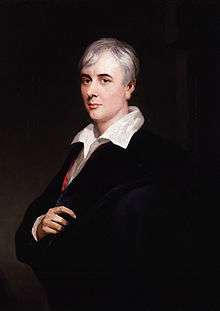

1843 portrait by Henry Wyndham Phillips at NPG | |

| Born |

5 July 1803 East Dereham, Norfolk |

| Died |

26 July 1881 (aged 78) Lowestoft, Suffolk |

| Occupation | author |

| Notable work | The Bible in Spain (1843); Lavengro (1851); Romany Rye (1857); Wild Wales (1862) |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Clarke (?-1869) |

| Parent(s) |

Ann Perfrement, Thomas Borrow |

George Henry Borrow (5 July 1803 – 26 July 1881) was an English author who wrote novels and travelogues based on his experiences traveling around Europe.[1] Over the course of his wanderings, he developed a close affinity with the Romani people of Europe, who figure prominently in his work. His best known books are The Bible in Spain, the autobiographical Lavengro, and The Romany Rye, about his time with the English Romanichal (gypsies).

Early life

Borrow was born at East Dereham, Norfolk, the son of Army recruiting officer Thomas Borrow (1758–1824)[2] and farmer's daughter Ann Perfrement (1772–1858).[3] He was educated at the Royal High School of Edinburgh and Norwich Grammar School.[4]

He studied law, but languages and literature became his main interests. In 1825, Borrow began his first major European journey, walking in France and Germany. Over the next few years he visited Russia, Portugal, Spain and Morocco, acquainting himself with the people and languages of the various countries he visited. After his marriage on 23 April 1840,[2] he settled in Lowestoft, Suffolk, but continued to travel both inside and outside the UK.

Borrow in Ireland

Having a military father, Borrow had a childhood of growing up at different posts. In the autumn of 1815, he accompanied the regiment to Clonmel in Ireland. There he attended the Protestant Academy, where he learned to read Latin and Greek ‘from a nice old clergyman’. He was also introduced to the Irish language by a fellow student named Murtagh, who tutored him in return for a pack of playing cards. In keeping with the political friction of the time, he learned to sing "the glorious tune 'Croppies Lie Down' " at the military barracks. He was introduced to horsemanship and learned to ride without a saddle. The regiment moved to Templemore early in 1816, and George took to ranging around the country on foot and later on horseback.

After less than a year in Ireland, the regiment returned to Norwich. With the threat of war having receded, the strength of the unit was greatly reduced.[5]

Early scandal

Because of his precocious linguistic skills, as a youth Borrow became the protégé of the Norwich-born scholar William Taylor. Borrow depicts Taylor, an advocate of German Romantic literature, in his semi-autobiographical novel Lavengro (1851). Recollecting his early youth in Norwich some thirty years earlier, Borrow depicts an old man (Taylor) and a young man (Borrow) discussing the merits of German literature, including Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther. Taylor confesses himself to be no admirer of either The Sorrows of Young Werther or its author but nevertheless states –

"It is good to be a German (for) the Germans are the most philosophical people in the world."

With Taylor’s encouragement, Borrow embarked upon his first translation: von Klinger's version of the Faust legend, entitled Faustus, his Life, Death and Descent into Hell, first published in St.Petersburg in 1791. In his translation, Borrow altered the name of one city, thus making one passage of the legend read –

"They found the people of the place modelled after so unsightly a pattern, with such ugly figures and flat features that the devil owned he had never seen them equalled, except by the inhabitants of an English town, called Norwich, when dressed in their Sunday's best."

For his lampooning of Norwich society, the young Borrow earned the humiliation of having Norwich public subscription library burn his first publication.

Russian visit

George Borrow was a linguist adept at acquiring new languages. He informed the British and Foreign Bible Society that –

"I possess some acquaintance with the Russian, being able to read without much difficulty any printed Russian book."

He left Norwich to travel to Saint Petersburg on 13 August 1833. As an agent of the Bible Society, Borrow was charged with supervising a translation of the Bible into Manchu. As a traveller, he was overwhelmed by the beauty of Saint Petersburg, writing –

Notwithstanding I have previously heard and read much of the beauty and magnificence of the Russian capital……There can be no doubt that it is the finest City in Europe, being pre-eminent for the grandeur of its public edifices and the length and regularity of its streets.

During his two-year sojourn in Russia, Borrow called upon writer Alexander Pushkin. The poet was out on a social visit. He left two copies of his translations of Pushkin's literary works and later Pushkin expressed his regret at not meeting him.

Borrow described the Russian people as –

"The best-natured kindest people in the world, and though they do not know as much as the English, they have not the fiendish, spiteful dispositions and if you go amongst them and speak their language, however badly, they would go through fire and water to do you a kindness."

Borrow had a lifelong empathy with nomadic people such as Gypsies. He was fascinated by gypsy music, dance and customs. He became so familiar with the Romany language as to publish a dictionary of it. In the summer of 1835, he visited Russian gypsies camped outside Moscow. His impressions formed part of the opening chapter of his The Zincali: or an account of the Gypsies of Spain (1841).

With his mission of supervising a Manchu translation of the Bible completed, Borrow returned to Norwich in September 1835. In his report to the Bible Society he confessed –

"I quitted that country, and am compelled to acknowledge, with regret. I went thither prejudiced against that country, the government and the people; the first is much more agreeable than is generally supposed; the second is seemingly the best adapted for so vast an empire; and the third, even the lowest classes, are in general kind, hospitable, and benevolent."

Spanish mission

Such was Borrow's success that on 11 November 1835 he set off for Spain, once more as an agent of the Bible Society. Borrow claimed to have stayed in Spain for nearly five years. His reminiscences of Spain were the basis of his travelogue The Bible in Spain (1843). He wrote sharply:

"[T]he huge population of Madrid, with the exception of a sprinkling of foreigners,...is strictly Spanish, though a considerable portion are not natives of the place. Here are no colonies of Germans, as at Saint Petersburg; no English factories, as at Lisbon; no multitudes of insolent Yankees lounging through the streets, as at the Havannah, with an air which seems to say, the land is our own whenever we choose to take it; but a population which, however strange or wild, and composed of various elements, is Spanish, and will remain so as long as the city itself shall exist."

The above quotation shows Borrow's empathy with native, indigenous peoples as well as his dislike for the growing 19th century phenomenon of American cultural imperialism.

Later life

In 1840 Borrow's career with the Bible Society came to an end, and he married Mary Clarke, a widow with a grown-up daughter called Henrietta, and a small estate at Oulton Broad in Lowestoft, Suffolk. There Borrow began to write his books. The Zincali (1841) was moderately successful, and The Bible in Spain (1843) was a huge success, making Borrow a celebrity overnight. But the eagerly awaited Lavengro (1851) and The Romany Rye (1857) puzzled many readers, who were not sure how much was fact and how much fiction (a question debated to this day). Borrow made one more overseas journey, across Europe to Istanbul in 1844, but the rest of his travels were in the UK, long walking tours in Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Cornwall and the Isle of Man. Of these, only the Welsh tour yielded a book, Wild Wales (1862).

Borrow's restlessness, perhaps, led to the family living in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, in the 1850s, and in London in the 1860s. Borrow visited the Romanichal Gypsy encampments in Wandsworth and Battersea, and wrote one more book, Romano Lavo-Lil, a wordbook of the Anglo-Romany dialect (1874). Mary Borrow died in 1869, and in 1874 he returned to Lowestoft, where he was later joined by his stepdaughter Henrietta and her husband, who looked after him until his death on 26 July 1881 in Lowestoft. He is buried with his wife in Brompton Cemetery, London.

Borrow was said to be a man of striking appearance and deeply original character. Although he failed to find critical acclaim in his lifetime, modern reviewers often praise his eccentric and cheerful style; "one of the most unusual people to have written in English in the last two hundred years" according to one critic.[6]

In 1913, the Lord Mayor of Norwich bought Borrow's house in Willow Lane; it was renamed Borrow House and was presented to the City of Norwich and was for many years open as the Borrow Museum.[7] The museum eventually closed and the house was sold in 1994; the funds were used to establish the George Borrow Trust which aims to promote Borrow's works.[8] There are Blue plaques marking his various residences in Hereford Square, Kensington in London, Trafalgar Road, Great Yarmouth and the former museum in Willow Lane, Norwich.[9] In December 2011, a plaque was unveiled on a house in Calle Santiago, Madrid, where he lived from 1836-40.[10] George Borrow Road, a crescent-shaped residential street in the west of Norwich is named after him. There is a George Borrow Hotel in Ponterwyd near Aberystwyth.

Principal works

|

|

Notes

- ↑ John Sutherland (1990) [1989]. "Borrow, George". The Stanford Companion to Victorian Literature. p. 77.

- 1 2 "Souvenir of the George Borrow Celebration". Gutenberg. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- ↑ "The Life of George Borrow". Fullbooks. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- ↑ Hooper, James (1913). Souvenir of the George Borrow Celebration. Jarrold & Sons. p. 14.

- ↑ ^ The Life of George Borrow. Fullbooks. Retrieved on 24 April 2008.

- ↑ Anthony Campbell (2002) - Lavengro and The Romany Rye

- ↑ Norwich Heritage, Economic & Regeneration Trust - George Borrow, Traveller and Writer, 1803-1881

- ↑ Literary Norfolk - Norwich - George Borrow (1803-1881)

- ↑ OPEN PLAQUES - George Borrow (1803-1881)

- ↑ Plaque unveiled in Spain to remember Dereham-born writer George Borrow

References

- W.I. Knapp: Life, writings and correspondence of George Borrow, London 1899

- R.A.J. Walling: George Borrow: The Man and His Work, London 1908

- T.H. Darlow (ed.): Letters of George Borrow to the British and Foreign Bible Society, London 1911

- H.G. Jenkins: The Life of George Borrow, London 1924, 2nd edition; 1912, 1st edition

- M.D. Armstrong: George Borrow, London 1950

- M. Collie: George Borrow, eccentric, Cambridge 1982

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: George Borrow |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: George Borrow |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about George Henry Borrow. |

- Works by George Borrow at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about George Borrow at Internet Archive

- Works by George Borrow at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The full text of Wild Wales: Its People, Language and Scenery on A Vision of Britain through Time, with links to the places Borrow mentions.

- George Borrow, by Edward Thomas. 1912 biography from Project Gutenberg

- George Borrow and His Circle (1913), by Clement King Shorter, 1857–1926, at Project Gutenberg

- Wherein May Be Found Many Hitherto Unpublished Letters Of Borrow And His Friends.

- The George Borrow Trust

- The George Borrow Society

- George Borrow and Norfolk

- George Borrow Studies

- The Life of George Borrow, by Herbert Jenkins. 1912