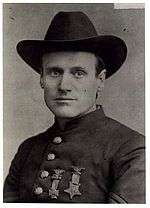

Gilbert Bates

Gilbert Henderson Bates (February 13, 1836–February 17, 1917) was an American soldier best known for his peaceful postwar marches, first throughout the American South and through England. For each endeavor, Bates wanted to prove that he would be treated cordially in regions supposedly hostile to Americans and found himself warmly welcomed by the natives.

American South march

Bates was born in Springwater, Livingston County, New York. He died in 1917 and was buried in Saybrook, Illinois. Before the American Civil War, Bates was a farmer in the town of Albion, near Edgerton, Wisconsin. During the war, he served as a sergeant in the 1st Wisconsin Heavy Artillery Regiment. After the war, he returned to his farm. In November 1867, during the period known as Reconstruction, Bates had a conversation about the South with a neighbor, who said, "Sergeant, the Southerners are rebels yet. They are worse now than they were during the war. They hate the Union flag. No man dare show that flag anywhere in the South except in the presence of our soldiers." Bates replied, "You are mistaken. I can carry that flag myself from the Mississippi all over the rebel States, alone and unarmed, too." Thus began his march, reported at the time in numerous local and national newspapers, but now largely forgotten.[1]

On February 27, 1868, Mark Twain published the following in the Territorial Enterprise:

Sergeant Gilbert H. Bates of Wisconsin is the last candidate for pedestrian notoriety. He has made a bet that he will walk, alone, unarmed, and without a cent in his pocket, and bearing aloft the American flag, through the late Southern Confederacy, from Vicksburg to Washington. He is already on his way, and the telegraph is noting his progress. The Mayor and a large portion of the population of Vicksburg ushered him out of that city with a grand demonstration. He proposes to sell photographs of himself at 25 cent apiece, all along his route, and convert the proceeds into a fund to be devoted to the aid and comfort of widows and orphans of soldiers who fought in the late war, irrespective of flag or politics.And then, I suppose, when he gets a good round sum together for the widows and orphans, he will hang up his flag and go and have a champagne blow-out. I don't believe in people who collect money for benevolent purposes and don't charge for it. I don't have full confidence in people who walk a thousand miles for the benefit of widows and orphans and don't get a cent for it. I question the uprightness of people who peddle their own photographs, anyhow, whether they carry flags or not. In my opinion a man might as well start his name with an initial and spell his middle name out and hope to be virtuous. But this fellow will get more black eyes, down there among those unreconstructed rebels than he can ever carry along with him without breaking his back. I expect to see him coming into Washington some day on one leg and with one eye out and an arm gone. He won't amount to more than an interesting relic by the time he gets here and then he will have to hire out for a sign for the Anatomical Museum. Those fellows down there have no sentiment in them. They won't buy his picture. They will be more likely to take his scalp.Gilbert Bates and the flag he carried

Bates won his bet. During a three-month "march", which started in Vicksburg where he was welcomed by the mayor, he walked 1,400 miles (2,300 km) across Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia to Washington, carrying the Stars and Stripes, and he was granted hospitality all along the way. He recorded his journey in a pamphlet published in June 1868 titled The Triumphal March of Sergeant Bates from Vicksburg to Washington. In an irony of the times, although he was allowed to raise his flag over numerous official buildings in the South, including the state Capitol in Richmond, he was not granted permission to fly it at the Capitol in Washington.

British march

Later, a wealthy friend of Bates's wagered $1,000 against $100 that Bates could not march the length of England carrying the Stars and Stripes without being insulted. This was due to the idea that many English supported the Confederacy during the Civil War because of cotton exports. On November 5, 1872, Bates, in full military uniform, began a 400 miles (640 km) march from the Scottish border to London. Throughout his travels in England, he was overwhelmed by the enthusiasm and kindness of the villagers. Hoteliers refused to let him pay; people fought to feed him. By the end of November, he had reached London, but the crowds were so great he had to be driven in an open carriage to the Guildhall, where he ceremoniously hung the unsullied Stars and Stripes next to the Union Jack. Upon reaching London, Bates telegrammed his friend, "Cancel wager. I regard this mission as something finer than a matter of money."

Artistic depiction

In September 2003, a dramatization of Bates's story titled "The Saga of Sergeant Bates: the Most Sensational March in American History", by John Nicholas Schweitzer, was commissioned by John Vorndran and produced for the Edgerton (Wisconsin) bicentennial.

References

- ↑ 'Encyclopedia of Media and Propaganda in Wartime America,' volume 1, Martin J. Manning and Clarence R. Wyatt-editors, ABC-CLIO, LCC. Santa Barbara, California: 2011, Biographical Sketch of Gilbert Henderson Bates, pg. 306-307

- The Triumphal March of Sergeant Bates from Vicksburg to Washington, Intelligence Printing House, Washington, 1868; a copy is available in the Wisconsin Historical Society. OCLC 17968634

- Gilbert Bates. Sergeant Bates' march, carrying the stars and stripes unfurled, from Vicksburg to Washington

- 5 Stupid Bets That Changed the World, by Eddie Rodriguez, for Cracked.com

External links

![]() Media related to Gilbert Bates at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gilbert Bates at Wikimedia Commons