Giles Corey

| Giles Corey | |

|---|---|

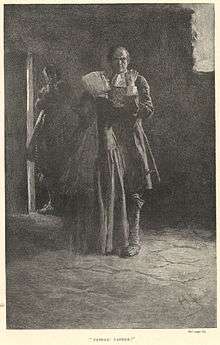

The pressing of Giles Corey | |

| Born |

September 11, 1611 Northampton, England |

| Died |

September 19, 1692 (aged 81) Salem, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation | Farmer |

| Criminal charge | Witchcraft (rehabilitated) |

| Criminal penalty | None ^ de jure |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Spouse(s) |

Margaret (1664–1664; her death) Mary Bright (1664–1684; her death) Martha Corey (1690–1692; his death) |

| Children | Deliverance (born on August 5, 1658) only child |

| Parent(s) | Giles and Elizabeth Corey |

Giles Corey (September 11, 1611 – September 19, 1692) was accused of witchcraft along with his wife Martha Corey during the Salem Witch Trials. After being arrested, Corey refused to enter a plea of guilty or not guilty. He was subjected to execution by pressing in an effort to force him to plead — the only example of such a sanction in American history — but instead died after two days of torture.

Corey is believed to have died in the field adjacent to the prison that had held him, in what later became the Howard Street Cemetery in Salem. His exact grave location in the cemetery is unmarked and unknown. There is a memorial plaque to him in the nearby Charter Street Cemetery, which sits in the commercial area catering to the tourist trade, but that is not historically relevant.

Pre-trial history

Giles Corey was born in Northampton, England, before 16 August 1611, the date on which he was baptized in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Giles was the son of Giles and Elizabeth Corey. His birth is recorded in the parish records of St. Sepulchre.[1] His name is quite often spelled Corey, but the baptismal record is Cory. It is not certain when exactly he arrived in the Americas, but there is evidence he was in Salem in 1640.[2] There are quite a few entries in the court documents as to his behavior, which was not completely good, but in those times any accusation was an offense against the state.[3]

Giles Corey was a prosperous land-owning farmer in Salem, and married three times.[4] He is believed to have married his first wife, Margaret, in England.[5] Margaret was the mother of his daughter, Deliverance.[1] His second wife was Mary Bright; they were married on April 11, 1664, when Corey was 43.[6]

In 1676, at the age of 65, Corey was brought to trial in Essex and accused of beating to death one of his indentured farm workers, Jacob Goodale, son of Robert Goodale and Catherine Kilham Goodale originally from Dennington, Suffolk, England. Jacob's brother was Isaac Goodale. Corey had severely beaten Goodale with a stick after Jacob was allegedly caught stealing apples from Corey's brother-in-law, and though Corey eventually sent him to receive medical attention 10 days later, Goodale died shortly thereafter. "Jacob was employed by Giles Corey, and in a quarrel with the latter was so badly beaten that he died, according to a coroner's jury, of blood clots about the heart caused by the blows. Corey was fined for the offense. Longfellow, in New England Tragedies, takes advantage of poetic license to substitute Robert' in his account." (Bowen: "Goodell Memorial Tablets"). Since corporal punishment was permitted against indentured servants, Corey was exempt from the charge of murder, and instead charged with using "unreasonable" force. Numerous witnesses and eyewitnesses testified against Corey, as well as the local coroner, and he was found guilty and fined.[7]

Mary Bright died at age 63 on August 27, 1684, according to her gravestone in Salem Graveyard. Corey later married his third wife, a woman referred to as "Lady Martha Perkins". Martha was admitted to the church at Salem Village (now Danvers), where Giles lived.

At the time of the witch trials, Corey was 80 years old and living with Martha in the southwest corner of Salem village, what is now Peabody.[8] Martha had a son from a previous marriage named Thomas; he showed up as a petitioner for loss and damages resulting from his mother being hanged illegally during the witch trials. He was awarded £50 on June 29, 1723.

Arrest, examination and refusal to plead

Giles Corey was arrested on April 18, 1692, along with Mary Warren, Abigail Hobbs and Bridget Bishop. The following day, they were examined by the authorities, during which Abigail Hobbs confessed to Giles being a warlock.

Corey refused to plead (guilty or not guilty), was committed to jail and subsequently arraigned at the September sitting of the court.

The records of the Court of Oyer and Terminer, September 9, 1692, contain a deposition by one of the girls who accused Giles of witchcraft..

Mercy Lewis v. Giles Corey: The Deposition of Mercy Lewis aged about 19 years who testified and said that on the 14th of April 1692 "I saw the Apparition of Giles Corey come and afflict me urging me to write in his book and so he continued most dreadfully to hurt me by times beating me & almost breaking my back tell the day of his examination being the 19th of April and then also during the time of his examination he did affect and tortor me most greviously: and also several times sense urging me vehemently to write in his book and I veryly believe in my heart that Giles Corey is a dreadful wizard for sense he had been in prison he or his appearance has come and most greviously tormented me." Mercy Lewis affirmed to the jury of Inquest. that the above written evidence: is the truth upon the oath: she has formerly taken in court of Oyer & Terminer: Septr 9: 1692

(property of the Supreme Judicial Court, Division of Archives and Records Preservation, on deposit at the Essex Institute)

Again, in this court, Corey refused to plead.[9]

Execution by pressing

According to the law at the time, a person who refused to plead could not be tried. To avoid persons cheating justice, the legal remedy for refusing to plead was "peine forte et dure". In this process the prisoner is stripped naked, with a heavy board laid on his body. Then rocks or boulders are laid on the plank of wood. This was the process of being pressed:[10]

remanded to the prison from whence he came and put into a low dark chamber, and there be laid on his back on the bare floor, naked, unless when decency forbids; that there be placed upon his body as great a weight as he could bear, and more, that he hath no sustenance, save only on the first day, three morsels of the worst bread, and the second day three draughts of standing water, that should be alternately his daily diet till he died, or, till he answered.

As a result of his refusal to plead, on September 17, Sheriff George Corwin led Corey to a pit in the open field beside the jail and in accordance with the above process, before the Court and witnesses, stripped Giles of his clothing, laid him on the ground in the pit, and placed boards on his chest. Six men then lifted heavy stones, placing them one by one, on his stomach and chest. Giles Corey did not cry out, let alone make a plea.

After two days, Giles was asked three times to plead innocent or guilty to witchcraft. Each time he replied, "More weight." More and more rocks were piled on him, and the Sheriff from time to time would stand on the boulders staring down at Corey's bulging eyes. Robert Calef, who was a witness along with other townsfolk, later said, "In the pressing, Giles Corey's tongue was pressed out of his mouth; the Sheriff, with his cane, forced it in again."[11]

Three mouthfuls of bread and water were fed to the old man during his many hours of pain. Finally, Giles Corey cried out "More weight!" and died. Supposedly, just before his death, he cursed Sheriff Corwin and the entire town of Salem.[12] He was 81.

Samuel Sewall's diary states, under date of Monday, September 19, 1692:

About noon at Salem, Giles Cory [sic] was pressed to death for standing mute; much pains was used with him two days, one after another, by the court and Captain Gardner of Nantucket who had been of his acquaintance, but all in vain.[13]

It is unusual for people to refuse to plead, and extremely rare to find reports of persons who have been able to endure this painful form of death in silence. Since Corey refused to plead, he died in full possession of his estate, which would otherwise have been forfeited to the government.[14] It passed on to his two sons-in-law, in accordance to his will.[15]

The pressing of Giles Corey is unique in New England. It is similar to the case, in England, of Margaret Clitherow, who was arrested on March 10, 1586 for the crime of harboring priests, hearing Mass, and secretly being of the Catholic faith.[16]

Legacy

Giles Corey is the subject of a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow play entitled Giles Corey of the Salem Farms and an 1893 play Giles Corey, Yeoman by Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman.

Corey is a character in Arthur Miller's play The Crucible (1953), in which he is portrayed as a hot-tempered but honorable man, giving evidence critical to the witch trials. His wife Martha (executed on September 22, 1692) was one of the 19 people hanged during the hysteria on Proctor's Ledge. In The Crucible, Giles feels guilty about the accusation of his wife because he had told a minister that Martha had been reading strange books, which was discouraged in that society. Corey also appears in Robert Ward's operatic treatment of the play, in which his role is assigned to a tenor.

According to a local legend of Salem, Massachusetts, the ghost of Giles Corey appears in Salem and walks his graveyard each time a disaster is about to strike the town. Notably, he was said to have appeared the night before the Great Salem Fire of 1914.[17] The position of Sheriff of Essex County was also said to have suffered from the "curse of Giles Corey", as the holders of that office since George Corwin had either died or resigned as a result of heart or blood ailments (Corwin himself died of a heart attack in 1696). The curse was said to have been broken when the Sheriff's office was moved from Salem to Middleton in 1991.[12][17]

British alternative and post-rock band I Like Trains wrote a song entitled "More Weight" about the execution of Corey.

If you don't choose a custom name in the online multiplayer party game Town of Salem, you automatically get assigned to a name of one of the victims of the Salem Witch Trials, one of them being Giles Corey.

American recording artist Dan Barrett has released solo material using the stage name Giles Corey.

American metalcore band Unearth wrote a song titled "Giles", which is about Corey's execution.

Actor Kevin Tighe portrayed Giles Corey in the pilot episode of the WGN television series Salem, in which he is executed in a more-or-less historically accurate manner.

References

- 1 2 http://coryfamsoc.com/genealogies/harpole/giles/giles/b70.htm

- ↑ "Corey Family Genealogy". freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Salem Witchcraft in American Drama". Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Geni". geni.com. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Geni". geni.com. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ Pope, Charles Henry. The pioneers of Massachusetts : a descriptive list, drawn from records of the colonies, towns, and churches, and other contemporaneous documents. Baltimore : Genealogical Pub. Co., 1991. p. 118. ISBN 9780806307749. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Records of the Essex Quarterly Courts". pp. 190–191.

- ↑ "Biography of Giles Corey".

- ↑ Salem Witch Trials: Giles Corey

- ↑ Salem Witch Trials of 1692

- ↑ Salem Witch Craft Trials

- 1 2 "Cold Spots - The Curse of Giles Corey - Dread Central". Dread Central.

- ↑ Goss, K. David (2008). The Salem Witch Trials: A Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 32.

- ↑ Hill, Frances A Delusion of Satan- the full story of the Salem Witch Trials Hamish Hamilton Ltd. 1995 pp.184–5

- ↑ Hill pp.184–5

- ↑ "Giles Corey and the Salem Witchcraft Trials".

- 1 2 "History of Massachusetts". historyofmassachusetts.org. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

Further reading

- Upham, Charles (1980). Salem Witchcraft. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 2 vv, v. 1 pp. 181–91, 205, v.2 pp. 38, 44, 52, 114, 121, 128, 334–43, 480, 483.

External links

![]() Media related to Giles Corey at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Giles Corey at Wikimedia Commons