Bog turtle

| Bog turtle Temporal range: 5–0 Ma Middle Pleistocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Subfamily: | Emydinae |

| Genus: | Glyptemys |

| Species: | G. muhlenbergii |

| Binomial name | |

| Glyptemys muhlenbergii (Schoepff, 1801) | |

| |

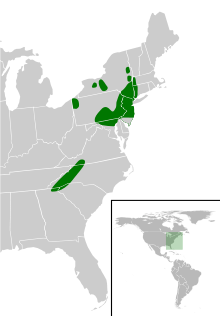

| Distribution. The range does not extend beyond the Canada–US border. | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) is a semiaquatic turtle endemic to the eastern United States. It was first scientifically described in 1801 after an 18th-century survey of Pennsylvania. The smallest North American turtle, it measures about 10 centimeters (4 in) long when fully grown. Although the bog turtle is similar in appearance to the painted or spotted turtles, its closest relative is actually the somewhat larger wood turtle. The bog turtle can be found from Vermont in the north, south to Georgia, and west to Ohio. Diurnal and secretive, it spends most of its time buried in mud and – during the winter months – in hibernation. The bog turtle is omnivorous, feeding mainly on small invertebrates.

Adult bog turtles weigh 110 grams (3.9 oz) on average. Their skins and shells are typically dark brown, with a distinctive orange spot on each side of the neck. Considered threatened at the federal level, the bog turtle is protected under the United States' Endangered Species Act. Invasive plants and urban development have eradicated much of the bog turtle's habitat, substantially reducing its numbers. Demand for the bog turtle is high in the black market pet trade, partly because of its small size and unique characteristics. Various private projects have been undertaken in an attempt to reverse the decline in the turtle's population.

The turtle has a low reproduction rate; females lay one clutch per year, with an average of three eggs each. The young tend to grow rapidly, reaching sexual maturity between the ages of 4 and 10 years old. Bog turtles live for an average of 20 to 30 years in the wild. Since 1973, the Bronx Zoo has successfully bred bog turtles in captivity.

Taxonomy

The bog turtle was noted in the 18th century by Gotthilf Heinrich Ernst Muhlenberg, a self-taught botanist and clergyman. Muhlenberg, who named more than 150 North American plant species, was conducting a survey of the flora of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, when he discovered the small turtle. In 1801, Johann David Schoepff named Muhlenberg's discovery as Testudo muhlenbergii in Muhlenberg's honor.[3][4][5]

In 1829, Richard Harlan renamed the turtle Emys muhlenbergii. The species was subsequently renamed to Calemys muhlenbergii by Louis Agassiz in 1857, and to Clemmys muhlenbergii by Henry Watson Fowler in 1906.[6] Synonyms include Emys biguttata, named in 1824 by Thomas Say on the basis of a turtle from the vicinity of Philadelphia, and Clemmys nuchalis, described by Dunn in 1917 from near Linville, North Carolina.[7] Today, there are various names for the bog turtle, including mud turtle, marsh turtle, yellowhead, and snapper.[8]

The genus name was changed to Glyptemys in 2001. The bog turtle and the wood turtle, Glyptemys insculpta, had until then been included in the genus Clemmys, which also included spotted turtles (C. guttata) and western pond turtles (C. marmorata).[9] Nucleotide sequencing and ribosomal DNA analyses suggested that bog turtles and wood turtles are closely related, but neither is directly related to spotted turtles, hence the separation of the genus Glyptemys.[10]

Description

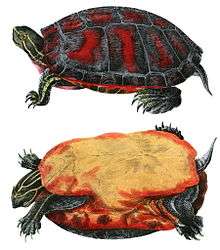

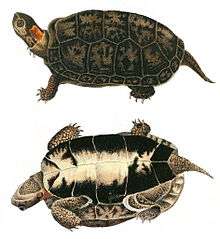

The bog turtle is the smallest species of turtle in North America.[11][12] The adults weigh approximately 110 grams (3.9 oz) when fully grown.[13] It does not have a prominent snout.[4] Its head is dark brown to black;[4] however, it has a bright yellow, orange, or red spot on each side of its neck.[8] The spot is often forked, facing posteriorly.[4] The bog turtle has a dark skin color with an orange-red wash on the inside of the legs of some individuals. The carapace is domed and rectangular in shape, and it tends to be narrower toward the head and wider toward the tail.[4] The carapace often has easily identifiable rings on the rough scales or scutes.[14] The scutes may also have a radiating arrangement of lines.[4] In some older individuals, and those that burrow frequently in coarse substrates, the shell may be smooth.[15] Although generally black, a chestnut sunburst pattern in each scute is sometimes present on the carapace.[8] The belly of the shell, the plastron, is also a dark brown to black color with light marks present.

The spotted turtle and painted turtle are similar in appearance to the bog turtle.[16] The bog turtle is distinguishable from any other species of turtle by the distinctively colored blotch on its neck. A major difference between it and the spotted turtle is that the bog turtle has no coloration on the upper shell, unlike the latter species.[17]

Mature male bog turtles have an average length of 9.4 centimeters (3.7 in) while the average female length is 8.9 centimeters (3.5 in) (straight carapace measurement).[15] The males have a larger average body size than females,[18] likely to facilitate males during male–male interactions during mate selection.[19] The female has a wider and higher shell than the male, but the male's head is squared and larger than a female's of the same age. The plastron of the male looks slightly concave while the female's is flat. The male's tail is longer and thicker than the female's.[20] The cloaca is further towards the end of the tail of the male bog turtle, while the female's cloaca is positioned inside the plastron.[12] Juveniles are very difficult to sex.[21]

Distribution and habitat

The bog turtle is native only to the eastern United States,[nb 1] congregating in colonies that often consist of fewer than 20 individuals.[24] They prefer calcareous wetlands (areas containing lime), including meadows, bogs, marshes, and spring seeps, that have both wet and dry regions.[20][25] Their habitat is often on the edge of woods.[26] Bog turtles have sometimes been seen in cow pastures and near beaver dams.[11]

The bog turtle's preferred habitat, sometimes called a fen, is slightly acidic with a high water table year-round.[27] The constant saturation leads to the depletion of oxygen, subsequently resulting in anaerobic conditions.[28] The bog turtle uses soft, deep mud to shelter from predators and the weather. Spring seeps and groundwater springs provide optimum locations for hibernation during winter. Home range size is gender dependent, averaging about 0.17 to 1.33 hectares (0.42 to 3.29 acres) for males and 0.065 to 1.26 hectares (0.16 to 3.11 acres) for females.[25] However, research has shown that densities can range from 5 to 125 individuals per 0.81 hectares (2.0 acres).[29] The range of the bog turtle extensively overlaps that of its relative, the wood turtle.[19]

Rushes, tussock sedge, cattails, jewelweed, sphagnum, and various native true grasses are found in the bog turtle's habitat, as well as some shrubs and trees such as willows, red maples, and alders. It is important for their habitat to have an open canopy, because bog turtles spend a considerable amount of time basking in the sunlight. An open canopy allows sufficient sunlight to reach the ground so that the bog turtles can manage their metabolic processes through thermoregulation. The incubation of eggs also requires levels of sunlight and humidity that shaded areas typically lack.[22] The ideal bog turtle habitat is early successional. Late successional habitats contain taller trees that block the necessary sunlight. Erosion and runoff of nutrients into the wetlands accelerate succession. Changes caused by humans have begun to eliminate bog turtles from areas where they would normally survive.[22]

Northern and southern populations

The northern and southern bog turtle populations are separated by a 400-kilometer (250 mi) gap over much of Virginia, which lacks bog turtle colonies.[12][30] In both areas, the bog turtle colonies tend to occupy widely scattered ranges.[24]

The northern population is the larger of the two. These individuals make their home in states as far north as Connecticut and Massachusetts, and as far south as Maryland. These turtles are known to have fewer than 200 habitable sites left, a number that is decreasing.[31]

The southern population is much smaller in number (only about 96 colonies have been located),[32] living in the states of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, and Tennessee.[12] This area in particular has seen about 90 percent of its mountainous wetlands dry up.[33] The turtles in this population are even more scattered than in the northern population and live at higher elevations, up to 1,373 meters (4,505 ft).[32]

Evolutionary history

There have been only two recorded discoveries of bog turtle fossils. The late J. Alan Holman, a paleontologist and herpetologist, first identified bog turtle plastral remains in Cumberland Cave, Maryland (near Corriganville), which are of Irvingtonian age (from 1.8 million to 300,000 years ago). The second discovery was of Rancholabrean (between 300,000 and 11,000 years ago) shell pieces in the Giant Cement Quarry in South Carolina (near Harleyville), by Bentely and Knight in 1998.[19]

The bog turtle's karyotype is composed of 50 chromosomes.[4] Studies of variations in mitochondrial DNA indicate low levels of genetic divergence among bog turtle colonies. This is unusual in species such as the bog turtle, which have fragmented distributions and exist in small isolated groups (fewer than 50 individuals in bog turtle colonies). These conditions limit gene flow, typically leading to divergence between isolated groups. Data indicate that the bog turtle suffered dramatic reductions in numbers – a population bottleneck – as colonies were forced south in the face of glaciation. Receding glaciers led to the relatively recent post-Pleistocene expansion, as the bog turtles moved back into their former northern range. This recent colonization from a relatively limited southern population may account for the reduction of genetic diversity.[34] The northern and southern populations are at present genetically isolated, likely as a consequence of farming and habitat destruction in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War.[32]

Ecology and behavior

Behavior

The bog turtle is primarily diurnal, active during the day and sleeping at night. It wakes in the early morning, basks until fully warm, then begins its search for food.[32] It is a seclusive species, making it challenging to observe in its natural habitat.[12] During colder days, the bog turtle will spend much of its time in dense underbrush, underwater, or buried in mud.[11] Such behavior is indicative of the bog turtle's ability to survive without oxygen.[35] On warmer days, the bog turtle's activities include scavenging, mating (during early spring), and basking in sunlight, the last of which it spends a great deal of the day doing.[22] However, the bog turtle usually takes shelter from the sun during the hottest part of the day.[32] Occasionally, during times of extreme heat, the turtle will either estivate,[36] or become subterranean, sometimes occupying networks of tunnels filled with water.[36] At night, the bog turtle buries itself in soft tunnels.[37]

Late September to March or April[36] is usually spent in hibernation, either alone or in small groups in spring seeps.[25] These groups can contain up to 12 individuals, and sometimes can include other species of turtles.[31] Bog turtles try to find an area of dense soil, such as a strong root system, for protection during the dormant period.[16] However, they may hibernate in other places such as the bottom of a tree, animal burrows, or empty spaces in mud.[31] The bog turtle emerges from hibernation when the air temperature is between 16 and 31 °C (61 and 88 °F).[35]

The male bog turtle is territorial and will attack other males if they venture within 15 centimeters (5.9 in) of his position. An aggressive male will crawl toward an intruder with his neck extended. As he approaches his foe, he tilts his carapace by withdrawing his head and raising his hind limbs. If the other male does not retreat, a fight of pushing and biting can follow. The bouts typically last just a few minutes,[35] with the larger and older male usually winning.[18] The female is also aggressive when threatened. She will defend the area around her nest, usually up to a radius of 1.2 meters (3.9 ft), from encroaching females, but when a juvenile approaches, she ignores it, and when a male appears she surrenders her area (except during mating season).[35]

Diet

Bog turtles are omnivorous and eat aquatic plants (such as duckweed), seeds, berries, earthworms, snails, slugs, insects, other invertebrates, frogs, and other small vertebrates.[23][38] They also occasionally eat carrion.[29] Invertebrates such as insects are generally the most important food item.[38] In captivity, a bog turtle can be fed a variety of fruits and vegetables, as well as meat such as liver, chicken hearts, and tinned dog food.[23] Bog turtles feed only during the day, but rarely during the hottest hours, consuming their food on land or in the water.[11][13]

Predators, parasites, and diseases

A host of different animals, including snapping turtles, snake species such as Nerodia sipedon and Thamnophis sirtalis, muskrats, striped skunks, foxes, dogs, and raccoons prey upon the bog turtle.[13][38] In addition, leeches (Placobdella multilineata and P. parasitica) and parasitic flies (Cistudinomyia cistudinis) plague some individuals, causing blood loss and weakness. Their shells offer little protection from predators. The bog turtle's main defense when threatened by an animal is to bury itself in soft mud. It rarely defends its territory or bites when approached.[38]

Bog turtles may suffer from bacterial infections. Aeromonas and Pseudomonas are two genera of bacteria that cause pneumonia in individuals.[39] Bacterial aggregates (sometimes known as biofilms) have also been found in the lungs of two deceased specimens discovered in 1982 and 1995 from colonies in the southern population.[40]

Movement

Day-to-day, the bog turtle moves very little, typically basking in the sun and waiting for prey. Though it is not especially lively on sunny days, the bog turtle is usually active after rainfall.[32] Various studies have found different rates of daily movement in bog turtles, varying from 2.1 to 23 meters (6.9 to 75.5 ft) in males and 1.1 to 18 meters (3.6 to 59.1 ft) in females.[41] Both sexes are capable of homing when released at distances up to 0.8 kilometers (0.50 mi) from their site of capture.[35] The bog turtle will travel long distances to find a new habitat if its home becomes unsuitable. The species is most active during the spring, and males generally exhibit greater migration distance and seasonal activity than females as they defend their territory. Home-range migration distances have been recorded at 87 meters (285 ft) for males and 260 meters (850 ft) for females.[42] Home-range sizes in Maryland vary from 0.0030 hectares (0.0074 acres) to 3.1 hectares (7.7 acres) with considerable amounts of variation between sites and years.[43]

The bog turtle is semiaquatic and can move both on land and in the water. The distance and frequency of movements on land help herpetologists understand the behavior, ecology, gene flow, and the level of success of different bog turtle colonies. The vast majority of bog turtle movements are less than 21 meters (69 ft), and only 2 percent are of distances over 100 meters (330 ft); large, expansive trips (i.e., between neighboring wetlands), are rare.[44]

The movement of bog turtles between colonies facilitates genetic diversity. If this movement were to be prevented, or limited in any significant way, the species would have a higher likelihood of becoming extinct because genetic diversity would fall. Some aspects of a bog turtle's movement that remain unresolved include: phenomena that motivate bog turtles to move outside their natural habitat; the distances an individual can be expected to travel each day, week, and year; and how separation of small groups affects the genetics of the species.[45]

Life cycle

.jpg)

Bog turtles are sexually mature when they reach between 8 and 11 years of age (both sexes).[26] They mate in the spring after emerging from hibernation, in a copulation session that usually lasts for 5–20 minutes, typically during the afternoon, and may occur on land or in the water. It begins with the male recognizing the female's sex. During the courtship ritual, the male gently bites and nudges the female's head. Younger males tend to be more aggressive during copulation, and females sometimes try to avoid an over-aggressive male. However, as the female ages, she is more likely to accept the aggressiveness of a male, and may even take the role of initiator. If the female yields, she may withdraw her front limbs and head. After the entire process is over, which usually takes about 35 minutes,[46] male and female go separate ways.[8] In a single season, females may mate once, twice, or not at all, and males try to mate as many times as possible.[46] It has been suggested that it is possible for the bog turtle to hybridize with Clemmys guttata during the mating season.[46] However, it has not been genetically verified in wild populations.

Nesting takes place between April and July.[8] The female digs a cavity in a dry, sunny area of a bog,[13] and lays her eggs in a grass tussock or on sphagnum moss.[47] The nest is typically 3.8 to 5.1 centimeters (1.5 to 2.0 in) deep and 5 centimeters (2.0 in) around.[46] Like most species of turtle, the bog turtle constructs its nest using its hind feet and claws. Most bog turtle eggs are laid in June. Pregnant females lay one to six eggs per clutch (mean of 3), and produce one clutch per year. A healthy female bog turtle can lay between 30 and 45 eggs in her lifetime, but many of the offspring do not survive to reach sexual maturity.[48] Typically, older females lay more eggs than younger ones.[46] The eggs are white, elliptical, and on average 3.4 centimeters (1.3 in) long and 1.5 centimeters (0.59 in) wide.[49] After the eggs are laid, they are left to undergo an incubation period that lasts for 42 to 80 days.[49] In colder climates, the eggs are incubated through the winter and hatch in the spring.[30] The eggs are vulnerable during the incubation period, and often fall prey to mammals and birds.[13] In addition, eggs may be jeopardized by flooding, frost, or various developmental problems. It is unknown how gender is determined in bog turtles.[49]

Baby bog turtles are about 2.5 centimeters (0.98 in) long when they emerge from their eggs,[15] usually in late August or September.[49] Females are slightly smaller at birth, and tend to grow more slowly than males.[49] Both genders grow rapidly until they reach maturity.[50] Juveniles almost double in size in their first four years, but do not become fully grown until five or six years old.[8]

The bog turtle spends its life almost exclusively in the wetland where it hatched. In its natural environment, it has a maximum lifespan of perhaps 50 years or more,[48] and the average lifespan is 20–30 years.[17] The Bronx Zoo houses several turtles 35 years old or more, the oldest known bog turtles. The zoo's collection has successfully sustained itself for more than 35 years.[51] The age of a bog turtle is determined by counting the number of rings in a scute, minus the first one (which develops before birth).[21]

Conservation

Protected under the United States Federal Endangered Species Act,[17] the bog turtle is considered threatened in Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania as of November 4, 1997. Due to a "similarity of appearance" to the northern population, the bog turtle is also threatened in Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia (considered to be the southern population).[22] In addition to the federal listing of threatened, states in the southern range list the bog turtle as either endangered or threatened.[40] Changes to the bog turtle's habitat have resulted in the disappearance of 80 percent of the colonies that existed 30 years ago.[8] Because of the turtle's rarity, it is also in danger of illegal collection, often for the worldwide pet trade.[52] Despite regulations prohibiting their collection, barter, or export, bog turtles are commonly taken by poachers.[22] Road traffic has also led to declines.[39] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has a plan for the recovery of the northern population.[53] The bog turtle was listed as critically endangered in the 2011 IUCN Red List.[54]

The invasion of non-native plants into its habitat is a large threat to the bog turtles' survival. Although several plants disrupt its ecosystem, the three primary culprits are purple loosestrife, reed canary grass, and reeds, which grow thick and tall and are believed to hinder the movement of the turtles. Such plants also out-compete the native species in the bog turtle's habitat, thus reducing the amount of food and protection available to the turtles.[55]

The development of new neighborhoods and roadways obstructs the bog turtle's movement between wetlands, thus inhibiting the establishment of new bog turtle colonies. Pesticides, runoff, and industrial discharge are all harmful to the bog turtles' habitat and food supply.[14] The bog turtle has been designated as a threatened species to "conserve the northern population of the bog turtle, which has seriously declined in the northeast United States."[56]

Today, the rebounding of bog turtle colonies depends on private intervention.[57] Population monitoring involves meticulous land surveys over vast countrysides.[58] In addition to surveying land visually, remote sensing has been used to biologically classify a wetland as either suitable or unsuitable for a bog turtle colony. This allows for comparisons to be made between known areas of bog turtle success and potential areas of future habitation.[59]

To help the existing colonies rebound, several private projects have been initiated in an attempt to limit the encroachment of overshadowing trees and bushes, the construction of new highways and neighborhoods, and other natural and man-made threats.[8]

Methods used to recreate the bog turtle's habitat include: controlled burns[55] to limit the growth of overshadowing trees and underbrush (thus bringing the habitat back to early successional);[50] grazing livestock such as cows and goats in the desired habitat area (creating pockets of water and freshly churned mud);[55][60] and promoting beaver activity, including dam construction in and around wetlands.[55]

Captive breeding is another method of stabilizing the bog turtles' numbers. The technique involves mating bog turtles indoors in controlled environments, where nutrition and mates are provided. Fred Wustholz and Richard J. Holub were the first to do this independently, during the 1960s and 1970s. They were interested in educating others about the bog turtle and in increasing its population, and over several years they released many healthy bog turtles into the wild.[8] Various organizations, such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, have been permitted to breed bog turtles in captivity.[61]

The study of bog turtles in the wild is a significant aid to the development of a conservation strategy. Radio telemetry has been used to track the turtles' movements in their natural habitat.[61] Blood samples, fecal samples, and cloacal swabs are also commonly collected from wild populations and tested for signs of disease.[62]

Notes

References

- Footnotes

- ↑ van Dijk, P.P. (2016). "Glyptemys muhlenbergii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2016: e.T4967A97416755. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 185–186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-17. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ↑ Schoepff, J. D. (1801). Historia testudinum iconibus illustrata. Erlangen: Sumtibus Ioannis Iacobi Palm.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ernst 2009, p. 263

- ↑ Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Glyptemys muhlenbergii, p. 184).

- ↑ Morse, Silas (1906). Annual report of the New Jersey State Museum. Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey State Museum. pp. 242–243.

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2001). Bog Turtle (Clemmys muhlenbergii), Northern Population, Recovery Plan (PDF). Hadley, Massachusetts. p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bloomer 2004, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Holman, J. A.; Fritz, U. (2001). "A new emydine species from the Middle Miocene (Barstovian) of Nebraska, USA with a new generic arrangement for the species of Clemmys sensu McDowell (1964) (Reptilia: Testudines: Emydidae)". Zoologische Abhandlungen Staatliches Museum für Tierkunde Dresden. 51: 331–354.

- ↑ Bickham, J. W. T.; Lamb, T.; Minx, P.; Patton, J. C. (1996). "Molecular systematics of the genus Clemmys and the intergeneric relationships of emydid turtles". Herpetologica. 52 (1): 89–97. JSTOR 3892960.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bog Turtle – Fact Sheet" (PDF). North Carolina Wildlife Resource Commission. 2006. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smith 2006, p. 1

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Bog Turtle". Department of Environmental Protection. State of Connecticut. 2002. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- 1 2 "Bog Turtle Fact Sheet". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- 1 2 3 Bloomer 2004, p. 2

- 1 2 "Bog Turtle" (PDF). Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. Archived from the original on 2009-09-12. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- 1 2 3 Shiels 2007, p. 23

- 1 2 Lovich, J. E.; Ernst, C. H.; Zappaloriti, R. T.; Herman, D. W. (1998). "Geographic variation in growth and sexual size dimorphism of bog turtles (Clemmys muhlenbergii)" (PDF). American Midland Naturalist. 139 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(1998)139[0069:GVIGAS]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0003-0031.

- 1 2 3 Ernst 2009, p. 264

- 1 2 "Bog Turtle, Clemmys muhlenbergii" (PDF). New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Species Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2004. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- 1 2 Walton 2006, p. 32

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shiels 2007, p. 24

- 1 2 3 Bloomer 2004, p. 3

- 1 2 Walton 2006, p. 23

- 1 2 3 Carter, Shawn L.; Haas, Carola A.; Mitchell, Joseph C. (1999). "Home range and habitat selection of bog turtles in southwestern Virginia" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Management. 63 (3): 853–860. doi:10.2307/3802798. JSTOR 3802798. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- 1 2 Smith 2006, p. 3

- ↑ Feaga, Jeffrey B.; Haas, Carola A.; Burger, James A. (2012). "Water Table Depth, Surface Saturation, and Drought Response in Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) Wetlands". Wetlands. 32 (6): 1011–1021. doi:10.1007/s13157-012-0330-8.

- ↑ Walton 2006, p. 28

- 1 2 Smith 2006, p. 4

- 1 2 "Bog Turtles". Keystone Wile Notes. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- 1 2 3 Smith 2006, p. 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ernst 2009, p. 265

- ↑ Walton 2006, p. 24

- ↑ Rosenbaum 2007, p. 331

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ernst 2009, p. 267

- 1 2 3 Ernst 2009, p. 266

- ↑ Bloomer 2004, p. 5

- 1 2 3 4 Ernst 2009, p. 270

- 1 2 Ernst 2009, p. 271

- 1 2 Carter, Shawn; Horne, Brian; Herman, Dennis (2005-09-03). "Bacterial pneumonia in free-ranging bog turtle, Glyptemys muhlenbergii, from North Carolina and Virginia" (PDF). Journal of the North Carolina Academy of Science. 121 (4): 170–173. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Ernst 2009, pp. 266–267

- ↑ Lovich, J. E.; Herman, D. W.; Fahey, K. M. (1992). "Seasonal activity and movements of bog turtles (Clemmys muhlenbergii) in North Carolina". Copeia. 1992 (4): 1107–1111. doi:10.2307/1446649. JSTOR 1446649.

- ↑ Morrow, J. L.; Howard, J. H.; Smith, S. A.; Poppel, D. K. (2001). "Home range and movements of the bog turtle (Clemmys muhlenbergii) in Maryland". Journal of Herpetology. 35 (1): 68–73. doi:10.2307/1566025. JSTOR 1566025.

- ↑ Carter, Shawn L.; Haas, Carola A.; Mitchell, Joseph C. (2000). "Movement and activity of bog turtles (Clemmys muhlenbergii) in southwestern Virginia" (PDF). Journal of Herpetology. 34 (1): 75–80. doi:10.2307/1565241. JSTOR 1565241. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ↑ Somers, Ann; Mansfield-Jones, Jennifer; Braswell, Jennifer (2007). "In stream, streamside, and under stream bank movements of a bog turtle, Glyptemys muhlenbergii" (PDF). Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 6 (2): 286–288. doi:10.2744/1071-8443(2007)6[286:ISSAUS]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1071-8443. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ernst 2009, p. 268

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 2–3

- 1 2 Walton 2006, p. 31

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ernst 2009, p. 269

- 1 2 Ernst 2009, pp. 270–271

- ↑ Herman, Dennis. Captive husbandry of the eastern Clemmys group at Zoo Atlanta. Proceedings First International Symposium on Turtles & Tortoises: Conservation & Captive Husbandry. California Turtle & Tortoise Club. pp. 54–62. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ Copeyon, Carole. "Bog turtles in North Carolina". Pennsylvania Field Office. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ "Bog Turtle (Clemmys muhlenbergii) Northern Population Recovery Plan" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- ↑ Van Dijk, P. P. "Glyptemys muhlenbergii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (ver. 2011.1). Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- 1 2 3 4 Shiels 2007, p. 25

- ↑ Copeyon, Carole (1997-11-05). "Bog turtles protected by Endangered Species Act". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ↑ Pittman 2009, p. 781

- ↑ Walton 2006, p. 20

- ↑ Walton 2006, p. 21

- ↑ Walton 2006, p. 30

- 1 2 Tryon, Bern W. (May 2009). "Defining success with bog turtle conservation in Tennessee". CONNECT. Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ↑ Brenner, Deena; Lewbart, G; Stebbins, M; Herman, DW (2002-01-17). "Health survey of wild and captive bog turtles" (PDF). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 33 (4): 311–316. PMID 12564526. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- Bibliography

- Bloomer, Tom J. (2004) [1970]. The Bog Turtle, Glyptemys muhlenbergii... A Natural History. Gainesville, Florida: LongWing Press. OCLC 57994322. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-30. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- Ernst, C. H.; Lovich, J. E. (2009). Turtles of the United States and Canada (2 ed.). JHU Press. pp. 263–271. ISBN 978-0-8018-9121-2.

- Palmer, William; Braswell, Alvin L. (1995). Reptiles of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 49–52. ISBN 0-8078-2158-6.

- Pittman, Shannon E.; Dorcas, Michael E. (2009). "Movements, Habitat Use, and Thermal Ecology of an Isolated Population of Bog Turtles (Glyptemys muhlenbergii)". Copeia. Lawrence, KS: American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists. 2009 (4): 781–790. doi:10.1643/CE-08-140. ISSN 0045-8511. Archived from the original on 2010-08-30. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- Rosenbaum, Peter A.; Robertson, Jeanne M.; Zamudio, Kelly R. (2007). "Unexpectedly low genetic divergences among populations of the threatened bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii)". Conservation Genetics. Springer Netherlands. 8 (2): 331–342. doi:10.1007/s10592-006-9172-3. ISSN 1566-0621. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- Shiels, Andrew L. (2007). "Bog Turtles Slipping Away" (PDF). Nongame and Endangered Species Unit. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Fish and Boat Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-30. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- Smith, Erika (October 2006). "Bog Turtle" (PDF). National Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- Walton, Elizabeth M. (2006). "II. Literature Review". Using Remote Sensing and Geographical Information Science to Predict and Delineate Critical Habitat for the Bog Turtle, Glyptemys muhlenbergii (PDF) (M.A. thesis). University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

External links

Media related to Glyptemys muhlenbergii at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Glyptemys muhlenbergii at Wikimedia Commons