Grace Cadell

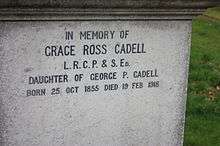

Dr Grace Ross Cadell MD RCPE RCSE (1855-1918) was an early Scottish pioneer physician, surgeon, novelist and militant suffragette.

Despite being what would now be seen as a heroine, she was viewed generally in her own day as a trouble-maker, and received no public recognition for any of her many good deeds. Whilst being granted a Licentiate from both the Royal College of Surgeons and Royal College of Physicians she was never permitted as a Fellow: the equivalent of being the member of a club which you cannot attend.

Life

She was the oldest of four daughters to George Philip Cadell of Carriden, Bo'ness, who was Superintendent of the local coalworks, and his wife Martina Duncanson Fleming, and was born on 25 October 1855.

In 1887 with her sister, Georgina Cadell, she became one of the students in the first ever intake at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women "run" by Sophia Jex-Blake. This was effectively an umbrella institution for channeling female students into the male-female extramural classes held by a small handful of the Edinburgh University's medical professors and lecturers who advocated the teaching of women (which was permitted in the university until 1892). However, this did not go smoothly. Both sisters were dismissed from the course. The issue seems to have been financial rather than academic, due to Jex-Blake taking what they considered an overly large fee in relation to the true cost of the extramural classes (i.e. the women were paying much more than the men). A court case ensued in 1889 in which the sisters were partly successful in suing Jex-Blake. Meanwhile, their studies continued under the more genial umbrella of fellow-student Elsie Inglis, who despite being only 24 and as yet unqualified, had set up a rival "college", the Edinburgh Medical College for Women, on the opposite side of town, working in exactly the same manner, purely giving an administrative avenue into the extramural classes. Both "schools" came to an effective end in 1892 when Edinburgh University began female admissions. Grace qualified in 1891 and therefore was never an official student at Edinburgh University (though taught by the same persons).[1]

At the same time Elsie Inglis had set up the Edinburgh Hospital for Women and Children, with an entirely female staff (quickly locally known as the Elsie Inglis Hospital), and the newly qualified Grace took on the critical role as the hospital’s first official Surgeon.[2]

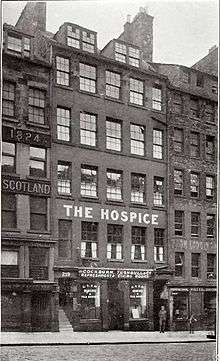

In 1899 when Elsie Inglis created the Medical Women's Club Grace served on the Committee. In 1904 she joined Inglis's clinic, The Hospice, on the Royal Mile running the gynaecology section as Consulting Obstetrician. In 1911 she took over Directorship of the whole clinic. She later became Registrar at the New Hospital for Women in London.[3]

On 9 October 1909 she was one of the many suffragettes on the public procession in Edinburgh demanding Votes for Women, locally named the “Gude Cause”.

An active suffragette Grace was president of the Leith branch of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1907 before re-aligning to the newly created Women's Freedom League (WFL). In 1912 as a result of refusing to pay taxes as a protest, her furniture was seized and publicly sold at the Mercat Cross on the Royal Mile. Grace turned the gathering into a suffrage meeting. During the Scottish Suffrage Campaign of 1913-14 (which involved attacks on specific buildings) Grace was medical advisor to those on hunger strike in prison.[4] Under the Cat and Mouse Act 1913 this often meant prisoners were released into her personal care to recover.[5] Ethel Moorhead was infamously released into her care following force-feeding at Calton Jail, as were both Edith Hudson and Arabella Scott.[6]

In another act of rebellion Grace refused to stamp her servant’s insurance card and was fined £50 by Lord Salvesen in the Glasgow High Court. The trial made the newspapers due to fellow-suffragettes throwing apples at the judge (but hitting one of the jurors), at the sentencing of other suffragettes for arson. Grace paid her fine with a sackful of copper coins as a further defiance.[7]

Her house at 145 Leith Walk[8] was a refuge for suffragettes.[9] It stood just north of Smiths Place but was demolished to create a printworks (Allander House). She never married but during the course of the First World War she adopted four children.

In July 1914 she attended the trial of Maude Edwards at Edinburgh Sherriff Court, when Maude was charged with slashing the portrait of King George V whilst hanging on display at the Royal Scottish Academy.[10] Maude was found guilty by Sheriff Maconochie and sentenced to three months imprisonment in Perth Prison (Perth being harder for her suffragette friends in Edinburgh to attend or to be a nuisance).[11] Grace had to be forcibly removed by three constables during the trial for causing an affray but was not arrested.

She died at Mosspark, on the Rumbling Bridge road at Yetts of Muckhart, on 19 February 1918.[12] However, she is not buried in the local churchyard at Muckhart but was instead returned to Edinburgh for burial with her parents and sisters in Morningside Cemetery.

In her will she left over £50,000 plus property and movable assets: a fortune in those days. This was given partly to remaining family and partly to her four adoptive children (only one of whom took her surname): Margaret Frances Clare Sydney; George Bell; Grace Emmeline Cadell; and Maurice Philip Shaw. Grace Emmeline was clearly named after Emmeline Pankhurst and is thought to have been adopted as a new-born from a young girl at the Magdalene House in Edinburgh, where unwed girls would have their children removed and made to work in “workhouse” conditions as “punishment” for getting pregnant. The other three (older children) are thought to have been from Dean Orphanage on the west of the city. Grace’s will gave all £150 per annum for the remainder of their lives. This is four or five times the average annual salary at the time.

Publications

Grace supplemented her income (her surgery often being pro bono) by writing novels about high society. Her most successful book was the Diary Illustrative of the Times of George IV.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women: From the Earliest Times to 2004, by Elizabeth Ewan, Sue Innes and Sian Reynolds

- ↑ British Medical Journal: obituaries: 9 March 1918

- ↑ British Medical Journal: obituaries: 9 March 1918

- ↑ Paris-Edinburgh: Cultural Connections in the Belle Epoque, by Sian Reynolds

- ↑ http://www.latebloomers.co.uk/wforum/ScottishSuffragists/gracecadell.html

- ↑ http://www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk/pdfs/ws-biog.aspx

- ↑ New York Times: October 16, 1913

- ↑ Edinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory 1911-12

- ↑ Edinburgh Evening Dispatch: 9 May 1914

- ↑ http://www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk/pdfs/ws-biog.aspx

- ↑ http://www.scottisharchivesforschools.org/suffragettes/maudeEdwards.asp

- ↑ British Medical Journal: obituaries: 9 March 1918

- ↑ http://media.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/wills_famousscots.php