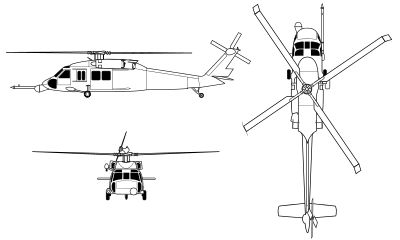

Sikorsky HH-60 Pave Hawk

| HH-60 / MH-60 Pave Hawk | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| U.S. Air Force HH-60G Pave Hawk | |

| Role | Combat search and rescue helicopter |

| Manufacturer | Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation |

| Introduction | 1982[1] |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Air Force Republic of Korea Air Force |

| Unit cost |

US$40.1 million (2011)[2] |

| Developed from | Sikorsky S-70 |

The Sikorsky MH-60G/HH-60G Pave Hawk is a twin turboshaft engine helicopter in service with the United States Air Force. It is a derivative of the UH-60 Black Hawk and incorporates the US Air Force PAVE electronic systems program. The HH-60/MH-60 is a member of the Sikorsky S-70 family.

The MH-60G Pave Hawk's primary mission is insertion and recovery of special operations personnel, while the HH-60G Pave Hawk's core mission is recovery of personnel under stressful conditions, including search and rescue. Both versions conduct day or night operations into hostile environments. Because of its versatility, the HH-60G may also perform peace-time operations such as civil search and rescue, emergency aeromedical evacuation (MEDEVAC), disaster relief, international aid and counter-drug activities.

Design and development

In 1981, the U.S. Air Force chose the UH-60A Black Hawk to replace its HH-3E Jolly Green Giant helicopters. After acquiring some UH-60s, the Air Force began upgrading each with an air refueling probe and additional fuel tanks in the cabin. The machine guns were changed from 0.308 in (7.62 mm) M60s to 0.50 in (12.7 mm) XM218s. These helicopters were referred to as "Credible Hawks" and entered service in 1987.[3]

Afterward, the Credible Hawks and new UH-60As were upgraded and designated MH-60G Pave Hawk. These upgrades were to be done in a two step process. But funding only allowed 16 Credible Hawks to receive the second step equipment. These helicopters were allocated to special operations use. The remaining 82 Credible Hawks received the first step upgrade equipment and were used for combat search and rescue. In 1991, these search and rescue Pave Hawks were redesignated HH-60G.[3][4]

The Pave Hawk is a highly modified version of the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk.[5] It features an upgraded communications and navigation suite that includes an integrated inertial navigation/global positioning/Doppler navigation systems, satellite communications, secure voice, and Have Quick communications. The term PAVE stands for Precision Avionics Vectoring Equipment.

All HH-60Gs have an automatic flight control system, night vision goggles lighting and forward looking infrared system that greatly enhances night low-level operations. Additionally, some Pave Hawks have color weather radar and an engine/rotor blade anti-ice system that gives the HH-60G an all-weather capability. Pave Hawk mission equipment includes a retractable in-flight refueling probe, internal auxiliary fuel tanks, two crew-served (or pilot-controlled) 7.62 mm miniguns or .50-caliber machine guns and an 8,000 pound (3,600 kg) capacity cargo hook. To improve air transportability and shipboard operations, all HH-60Gs have folding rotor blades.

Pave Hawk combat enhancements include a radar warning receiver, infrared jammer and a flare/chaff countermeasure dispensing system. HH-60G rescue equipment includes a hoist capable of lifting a 600-pound (270 kg) load from a hover height of 200 feet (60 m), and a personnel locating system. A number of Pave Hawks are equipped with an over-the-horizon tactical data receiver that is capable of receiving near real-time mission update information.[6]

Operational history

As of 2015, the U.S. Air Force HH-60G Pave Hawk is operated by the Air Combat Command (ACC), U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), Pacific Air Forces (PACAF), Air Education and Training Command (AETC), the Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC) and the Air National Guard (ANG). A number of HH-60Gs are also operated by the Air Force Material Command (AFMC) for flight test purposes.[6]

During Operation Desert Storm, Pave Hawks provided combat search and rescue coverage for coalition Air Forces in western Iraq, Saudi Arabia, coastal Kuwait and the Persian Gulf. They also provided emergency evacuation coverage for U.S. Navy sea, air and land (SEAL) teams penetrating the Kuwaiti coast before the invasion.[6]

All MH-60Gs were subsequently divested by Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) in 1991. At that time, most MH-60Gs were redesignated as HH-60Gs and transferred to Air Combat Command (ACC) and ACC-gained Air Force Reserve Command and Air National Guard units.[3][4]

During Operation Allied Force, the Pave Hawk provided continuous combat search and rescue coverage for NATO air forces, and successfully recovered two U.S. Air Force pilots who were isolated behind enemy lines.[6]

In March 2000, three Pave Hawks deployed to Hoedspruit Air Force Base in South Africa, to support international flood relief operations in Mozambique. The HH-60Gs flew 240 missions in 17 days and delivered more than 160 tons of humanitarian relief supplies.[6]

Air Force Pave Hawks from the Pacific theater also took part in a massive humanitarian relief effort in early 2005 in Sri Lanka to help victims of the tsunami.[7] In the fall of 2005, Pave Hawks from various Air Force commands participated in rescue operations of Hurricane Katrina survivors, rescuing thousands of stranded people.[6]

Pave Hawks have regularly operated during Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation New Dawn, and continue to be operated in Operation Enduring Freedom, supporting Army and Marine Corps ground combat operations and standby search and rescue support for U.S. and Coalition fixed-wing combat aircraft supporting those ground operations.[6]

Replacement

In 1999, the USAF identified a need for a helicopter with improved range, speed, and cabin space. An options analysis was completed in 2002 and funding for 141 aircraft under the "personnel recovery vehicle" program began in 2004. In 2005, it was renamed CSAR-X, meaning combat search and rescue. Sikorsky entered the HH-92 Superhawk, Lockheed Martin entered the VH-71 Kestrel, and Boeing entered the HH-47 Chinook. The HH-47 won the competition in November 2006, but the award was cancelled after successful protests from both rival competitors. A Request for Proposals (RFP) was reissued in 2007, but protested again before proposals were received, leading to a second cancellation.[8] In March 2010, the USAF announced a recapitalization plan to return its 99-aircraft inventory to 112 airframes, incrementally replacing aging HH-60Gs; a secondary plan to replace 13 attrition HH-60s, seven of which were lost in combat since 2001, was also been initiated. The USAF deferred secondary combat search and rescue requirements calling for a larger helicopter. A UH-60M-based version was offered as a replacement.[9][10][11]

On 22 October 2012, the USAF issued an RFP for up to 112 Combat Rescue Helicopters (CRH) to replace the HH-60G with the primary mission of personnel recovery from hostile territory; other missions include civil search and rescue, disaster relief, casualty and medical evacuation.[12] It had to have a combat radius of 225 nmi (259 mi; 417 km), a payload of 1,500 lb (680 kg), and space for up to four stretchers. The AgustaWestland AW101 was one entrant.[13] By December 2012, competitors AgustaWestland, EADS, Boeing, and Bell Helicopter had withdrawn amid claims that the RFP favored Sikorsky and did not reward rival aircraft's capabilities.[14][15] The USAF argued that the competition was not written to favor Sikorsky, and that the terms were clear as to the capabilities they wanted and could afford. Sikorsky was the only bidder remaining, with subcontractor Lockheed Martin supplying mission equipment and the electronic survivability suite. Sikorsky and the USAF extensively evaluated the proposed CRH-60, a variant of the MH-60 special operations helicopter;[16] the CRH-60 differed from the MH-60 by its greater payload and cabin capacity, wider rotor blades, and better hover capability.[8]

In September 2013, the initial USAF FY 2015 budget proposal would have cancelled the CRH program due to sequestration budget cuts, instead retaining the HH-60 fleet,[17] but Congress stated it would add CRH funding if the USAF could not.[18] Over $300 million was allocated to the program in FY 2014, with $430 million to be moved from other areas through FY 2019 to finance it.[19] On 26 June 2014, the USAF awarded Sikorsky and Lockheed Martin a $1.3 billion contract for the first four aircraft, with 112 total to be procured for up to $7.9 billion.[20] Five more are to be delivered by 2020, the order is to be completed by 2029.[21] On 24 November 2014, the Air Force officially designated the UH-60M-derived CRH as the HH-60W "60 Whiskey."[1]

Variants

- HH-60A: Prototype for the HH-60D rescue helicopter. A modified UH-60A primarily designed for combat search and rescue. It is equipped with a rescue hoist with a 200 ft (60.96 m) cable that has a 600 lb (270 kg) lift capability, and a retractable in-flight refueling probe.[22]

- HH-60D Night Hawk: Prototype of combat rescue variant for the US Air Force.

- HH-60E: Proposed search and rescue variant for the US Air Force.

- HH-60G Pave Hawk: Search and rescue helicopter for the US Air Force upgraded from UH-60A Credible Hawk.

- MH-60G Pave Hawk: Special Operations, search and rescue model for the US Air Force. Equipped with long-range fuel tanks, air-to-air refueling capability, FLIR, improved radar. Powered by T-700-GE-700/701 engines.[22]

- Maplehawk: Proposed search and rescue version for the Canadian Forces to replace aging CH-113 Labradors.[23] The CF opted for the CH-149 Cormorant instead.

- HH-60P Pave Hawk: Combat Search and Rescue variant of UH-60P, in service with Republic of Korea Air Force. Variant includes External Tank System and FLIR for night operations.[24]

- HH-60W: Combat rescue helicopter variant of the UH-60M for the U.S. Air Force to replace the HH-60G.[1]

Operators

- Republic of Korea Air Force operates HH-60P helicopters[25]

- United States Air Force[25]

- 33d Rescue Squadron[26]

- 41st Rescue Squadron[27]

- 55th Rescue Squadron[28]

- 56th Rescue Squadron[29]

- 66th Rescue Squadron[30]

- 101st Rescue Squadron[31]

- 129th Rescue Squadron[32]

- 210th Rescue Squadron[33]

- 301st Rescue Squadron[34]

- 305th Rescue Squadron[35]

- 413th Flight Test Squadron[36]

- 512th Rescue Squadron [37]

Specifications (HH-60G)

Data from USAF 2008 Almanac[5] USAF fact sheet,[6]

General characteristics

- Crew: 4 (2 pilots, 2 special mission aviators/aerial gunners)

- Capacity: max. crew 6, 8–12 troops, plus litters and/or other cargo

- Length: 64 ft 10 in (17.1 m)

- Rotor diameter: 53 ft 8 in (14.1 m)

- Height: 16 ft 8 in (5.1 m)

- Empty weight: 16,000 lb (7,260 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 22,000 lb (9,900 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric T700-GE-700/701C turboshaft, 1,630 shp (1,220 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 195 knots (224 mph, 360 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 159 kt (184 mph, 294 km/h)

- Range: 373 mi (internal fuel), or 508 mi (with external tanks) (600 km, or 818 km)

- Service ceiling: 14,000 ft (4,267 m)

Armament

Onboard systems

- INS/GPS/Doppler navigation

- SATCOM satellite communications

- Secure/anti-jam communications

- LARS (Lightweight Airborne Recovery System) range/steering radio to compatible survivor radios

- Automatic flight control

- NVG night vision goggle lighting

- FLIR forward looking infra-red radar

- Color weather radar

- Engine/rotor blade anti-ice system

- Retractable In-flight refueling probe

- Integral rescue hoist

- RWR combat enhancement

- IR infra-red jamming unit

- flare/chaff countermeasure dispensing system

See also

- Related development

- Sikorsky H-92 Superhawk

- Sikorsky MH-60 Jayhawk

- Sikorsky S-70

- Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk

- Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

- Notes

- 1 2 3 USAF toasts Whiskey designation for CRH fleet - Flightglobal.com, 28 November 2014

- ↑ "HH-60G Pave Hawk". U.S. Air Force. United States Air Force. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 Eden, Paul. "Sikorsky H-60 Black Hawk/Seahawk", Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- 1 2 Bishop, Chris. Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk. Osprey, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84176-852-6.

- 1 2 Young, Susan H.H., Staff Editor (May 2008). ""HH-60G Pave Hawk", 2008 USAF Almanac – Gallery of USAF Weapons" (PDF). Air Force Magazine. Air Force Association. 91 (5): 155–156. ISSN 0730-6784.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "HH-60G Pave Hawk". United States Air Force. 4 February 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ Gempis, Master Sgt. Val. "Kadena Airmen help Sri Lanka tsunami victims". Air Force Print News, 18 January 2005.

- 1 2 Sikorsky eyes federal budget amid uncertainty over combat rescue helicopter - Flightglobal.com, 19 December 2013

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen. "USAF abandons large helicopter for rescue mission, proposes buying 112 UH-60Ms". Flight International. 24 February 2010.

- ↑ USAF HH-60 Personnel Recovery Recapitalization Program (HH-60 Recap) sources sought notice. fbo.gov, Released" 23 March, Revised: 8 April 2010.

- ↑ Reed, John. "UH-60M Offered For USAF's New CSAR Program". Defense News, 15 July 2010.

- ↑ Air Force Releases RFP for Next Search And Rescue Helicopter Af.mil, 22 October 2012.

- ↑ US Air Force moves forward with CSAR procurement Flightglobal.com, 31 October 2012

- ↑ Most contractors opt out of Air Force chopper bids Reuters, 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Sikorsky last bidder standing in USAF's combat rescue helicopter battle Flightglobal.com, 12 December 2012.

- ↑ U.S. Air Force delays rescue helicopter contract award - Reuters.com, 2 August 2013

- ↑ USAF Weighs Scrapping KC-10, A-10 Fleets Defensenews.com, 15 September 2013.

- ↑ Aide: Congress Will Fight To Fund Combat Rescue Helo - Defensenews.com, 18 February 2014

- ↑ USAF to issue contract to Sikorsky for rescue helicopter - Flightglobal.com, 4 March 2014

- ↑ Sikorsky, Lockheed awarded Combat Rescue Helo contract - Militarytimes.com, 26 June 2014

- ↑ Sikorsky awarded up to $7.9 billion rescue helicopter deal - Flightglobal.com, 27 June 2014

- 1 2 DoD 4120-15L, Model Designation of Military Aerospace Vehicles. US DoD, 12 May 2004.

- ↑ Warwick, Graham (27 September 2008). "Level Playing Field?". Flight International. Reed Business Information. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ↑ http://www.koreadefence.net/wys2/file_attach/2009/10/08/1255007427-9.jpg

- 1 2 "World Air Forces 2014" (PDF). Flightglobal Insight. 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ↑ "33d Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "41st Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "55th Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "56th Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "66th Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "101st Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "129th Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "210th Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "301st Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "305th Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "413th Flight Test Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "512th Rescue Squadron". af.mil. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- Bibliography

- Leoni, Ray D. Black Hawk: The Story of a World Class Helicopter. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2007. ISBN 978-1-56347-918-2.

- Tomajczyk, Stephen F. Black Hawk. MBI, 2003. ISBN 0-7603-1591-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sikorsky HH-60 Pave Hawk. |

- USAF HH-60G Pave Hawk fact sheet

- HH-60 page and MH-60 page on globalsecurity.org

- Sikorsky S-70 page on helis.com