HMS Dryad (1866)

.jpg) HMS Dryad at anchor, with sails airing | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Dryad |

| Builder: | Devonport Dockyard |

| Laid down: | April 1865[1] |

| Launched: | 25 September 1866 |

| Decommissioned: | September 1885 |

| Honours and awards: | Abyssinia (1868) |

| Fate: | Broken up in April 1886 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Screw Sloop |

| Displacement: | 1,574 tons |

| Length: | 187 ft (57 m) |

| Beam: | 36 ft (11 m) |

| Draught: | 17 ft (5.2 m)[2] |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Sail plan: | Barque-rigged |

| Speed: | 11.9 knots (22.0 km/h) |

| Complement: | 150 (170 after armament converted) |

| Armament: |

|

HMS Dryad was a 4-gun Amazon-class screw sloop, launched at Devonport in 1866. She served on the East Indies and North American Stations, taking part in the Abyssinian War, a confrontation with the French at Tamatave and the Egyptian War. She was sold for breaking in 1885.

Design

Designed by Edward Reed,[1] the Royal Navy Director of Naval Construction, the hull was built of oak, with teak planking and decks, and she was equipped with a ram bow.[1]

Propulsion

Propulsion was provided by a two-cylinder horizontal single-expansion steam engine by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Company driving a single 15 ft (4.6 m) screw.[1]

Sail Plan

All the ships of the class were built with a barque rig.[1]

Armament

The class was designed with two 7-inch (180 mm), 6½-ton muzzle-loading rifled guns mounted on slides on centre-line pivots, and two 64-pounder muzzle-loading rifled guns on broadside trucks. Dryad, Nymphe and Vestal were rearmed in the early 1870s with an armament of nine 64-pounder muzzle-loading rifled guns, four each side and a centre-line pivot mount at the bow.[1]

History

1866 – 1868

Dryad's keel was laid in April 1865,[1] and she was launched on 25 September 1866.[3] Her first Captain was Commander Thomas Fellowes, who took command on 3 May 1867,[4] and under whom she formed part of the East Indies Fleet.[4]

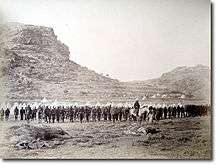

Abyssinian War (1868)

.jpg)

In 1868, the ship's company of Dryad took part in the Abyssinian War. A Naval Brigade, composed of 80 men from several ships, was landed at Zula on 25 January, and was placed under the command of Commander Fellowes.[5] They were armed with 12-pound rockets, which were ideally suited to operations in the rugged terrain of Abyssinia. William Simpson of the Illustrated London News reported that

It's armament consists of twelve rocket tubes; each tube can be carried upon a mule, with two boxes of ammunition. Within fifty or sixty seconds after the order is given to prepare for action, the tubes can be made all ready and the firing may begin.[6]

The Brigade marched inland, and joined the main force under Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Napier, the Commander-in-Chief at Santara on 30 March. The "Blue Jackets" rendered valuable service during the action at Arogye on 10 April,[7] where they led the attack up the King’s Road.

On 13 April, they took part in the assault and capture of Magdala, throwing rockets into the town. The Brigade sustained no casualties at Magdala, and behaved admirably, earning the warm praise of the Commander-in-Chief.[7] By 10 June, the campaign was over and the British forces had re-embarked at Zula.

Commander Philip Howard Colomb relieved Fellows as Captain of Dryad on 6 July 1868, Commander Fellows apparently being invalided out of the ship. Shortly afterwards, on 14 August,[4] Commander Fellowes was promoted to Post-Captain for his services. "Abyssinia (1868)" constitutes the second battle honour awarded to Dryad: the first, "Proserpine (1796)", was inherited from the first ship named HMS Dryad.

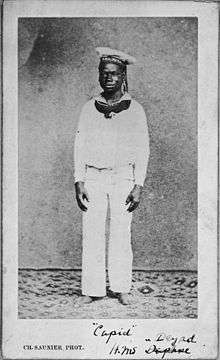

Anti-Slavery on the East Indies Station (1868–1872)

Dryad continued to serve on the East Indies Station until 1872. Under Colomb she worked in and around the Persian Gulf, Oman and Zanzibar, engaged in the suppression of slavery. Colomb's experiences are captured in his book Slave-catching in the Indian Ocean: A record of naval experiences, published by Longmans of London in 1873. He captured seven slave ships[8] during his two years in the Indian Ocean, and returned to Britain a lionised figure, courted by the press.

Commander George Parsons relieved Colomb on 11 April 1870 and commanded Dryad until 26 April 1872.

Out of commission (1872–1874)

Dryad’s first commission ended on 26 April 1872,[5] when Commander Parsons left her in Devonport. Normal practice of the time was for the ship's company to leave the ship upon decommissioning, with the exception of a few specialists, including the shipwright and gunner, who would have been accommodated in another vessel. The dockyard would have taken her in hand for a refit, and she would have recommissioned, with a new captain and crew, on completion.

North American and West Indies Station (1874–1879)

Commander Compton Edward Domvile re-commissioned Dryad on 13 August 1874 and took her to the North America and West Indies Station. Domville, who went on to become Admiral Sir Compton Domville, was promoted to Captain on 27 March 1876. He was relieved in 1877 by Commander John Edward Stokes, who commanded her until 14 December 1877.

Out of commission (1877–1879)

From 1877 to 1879 she was out of commission at Devonport. Her Chief Engineer and Carpenter were carried on the books of HMS Indus. During this period her armament was changed from a mixture of 7-inch and 64-pounder muzzle-loading rifled guns to nine 64-pounder muzzle-loading rifled guns.[1]

East Indies Station (1879–1882)

Commander John Hext joined Dryad on 18 December 1879, and commanded her in the East Indies Station until 30 June 1882. He was succeeded as Captain by Commander Charles Johnstone.

Tamatave (1883)

On 15 February 1883, François Césaire de Mahy, who was a Réunion deputy and French Minister of Agriculture (and at the time also temporarily filled the post of Minister of Marine), ordered Rear Admiral Pierre to enforce French claims in Madagascar, starting the first Franco-Hova War.[9] Pierre's squadron arrived at Tamatave on 31 May to find Dryad already anchored in the roadstead. The French delivered an ultimatum to the foreign consuls to withdraw, but Mr Pakenham, the British consul, was already a seriously ill man; seven hours after the ultimatum was delivered he died of his illness. Commander Johnstone, already intending to protect the interests of British residents, readily took on the duty of consul. As well as the inevitable damage and distress caused in the bombardment, further controversy was added when Admiral Pierre arrested an Englishman:

The French Admiral, after delivering an ultimatum, which was rejected, bombarded and occupied Tamatave, and destroyed other Hova establishments on the East coast. Mr Shaw, an English medical missionary, was established at Tamatave, and beyond rendering medical assistance to the wounded natives, took no part in the struggle. Nevertheless, his dispensary was broken into, he was arrested, accused of poisoning French soldiers [footnote: Who had made themselves ill by appropriating and drinking his claret – that was all.], and was closely confined as a prisoner on the French flagship.[10]

Admiral Pierre took possession of Tamatave on 11 June, and a standoff ensued between the two navies. On 16 July, the New York Times was able to report that

The Captain of the English war vessel Dryad has offended the French by landing a guard of marines at the British consulate, and placing his boats at the disposal of fugitives.[11]

In Britain, the press railed against 'French atrocities' and in France the equally virulent media insisted that the British were too inclined to exceed their rights as neutrals. Coming at the same time as a French expedition to Indochina, and seeking to maintain cordial relations, the issues were downplayed by both governments. On 14 August, Admiral Galiber sailed from Toulon to relieve Pierre, arriving in Madagascar in October.[12] The French intervention in Madagascar had moved the region towards French domination, but it was not until 1895 that the entire island came under their control. Much of the reason for this ten-year delay is the delaying tactics of Commander Johnstone; as well as being hailed for his tact and heroism by the British press, he was promoted to Captain on 21 November.[13] He left Dryad in January 1884.

Egyptian War (1884)

Commander Edward Grey Hulton took command in January 1884,[14] and under his command some of her ship's company formed part of the Naval Brigade which accompanied the army under General Sir Gerald Graham. The Naval contingent consisted of 150 seamen and 400 Royal Marines. They came from a number of ships lying off Suakin which joined others at Trinkitat to offload the Expeditionary Force.

After marching inland, the Brigade took part in the battle of El Teb. It was at this battle that Captain Arthur Knyvet Wilson of HMS Hecla earned the Victoria Cross for his conspicuous bravery in fighting with his fists, and saving one corner of the British square from being broken. After the battle of El Teb, the General Commanding issued a general order in which he especially thanked the Naval Brigade for their cheerful endurance during the severe work of dragging the guns over difficult country, and for their ready gallantry and steadiness under fire. On 11 March, the Naval Brigade advanced from Suakin with the troops for the dispersal of the Arab forces who were beleaguering Sinkat.

On 12 March, the expeditionary force took part in the Battle of Tamai. The Naval Brigade charged the Arabs, was surrounded, and lost their guns. Order was at length restored, and the Naval Brigade, advancing again, had the satisfaction of regaining all their guns; the Arab forces retired after suffering a loss of 2,000 killed. The total British loss was 109 killed and 104 wounded, of which the Naval Brigade lost 3 officers and 7 men killed, and 1 officer and 6 seamen wounded. Among the killed was Lieutenant Houston Stewart of Dryad, who died while defending the guns

Decommissioning and fate

Dryad was decommissioned for the last time at Sheerness[5] in November 1884. She was sold in September 1885 and broken up in April 1886.[1]

Commanding officers

| From | To | Captain |

|---|---|---|

| 3 May 1867 | 6 July 1868 | Commander Thomas Hounsom Butler Fellowes[15] |

| 6 July 1868 | 11 April 1870 | Commander Philip Howard Colomb[15] |

| 11 April 1870 | 26 April 1872 | Commander George Parsons[15] |

| 26 April 1872 | 13 August 1874 | Out of commission (Plymouth) |

| 13 August 1874 | 1877 | Commander Compton Edward Domvile[15] |

| 1877 | 14 December 1877 | Commander John Edward Stokes[15] |

| 14 December 1877 | 18 December 1879 | Out of commission (Plymouth) |

| 18 December 1879 | 30 June 1882 | Commander John Hext[15] |

| 30 June 1882 | January 1884 | Commander Charles Johnstone[15] |

| January 1884 | 10 November 1884 | Commander Edward Grey Hulton[15] |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Winfield, Rif & Lyon, David (2004). The Sail and Steam Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy 1815–1889. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-032-6. OCLC 52620555.

- 1 2 "Cruisers at Battleships-Cruisers website". Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ↑ "HMS Dryad at the Naval Database website". Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- 1 2 3 "William Loney RN website – Thomas Hounsom Butler Fellowes Biography". Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- 1 2 3 "William Loney RN website – HMS Dryad Biography". Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ↑ Diary of a Journey to Abyssinia 1868: The Diary and Observations of William Simpson, by William Simpson, Richard Pankhurst, Frederic Sharf, published by Tsehai Publishers, 2002, ISBN 0-9723172-1-X

- 1 2 "The history of the name Dryad at Battleships-Cruisers website". Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ↑ Lewis-Jones, Huw. "The Royal Navy and the Battle to End Slavery". BBC. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ↑ An Economic History of Imperial Madagascar, 1750–1895:The Rise and Fall of an Island Empire, by Gwyn Campbell, Cambridge University Press, 2005 ISBN 0-521-83935-1

- ↑ A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races, by Harry Hamilton Johnston, University Press, Cambridge, 1905 reprinted by the Adamant Media Corporation, 2002, ISBN 0-543-95979-1

- ↑ New York Times, 16 July 1883

- ↑ New York Times, 29 July 1883

- ↑ "William Loney RN Website – biography of Charles Johnstone". Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ↑ "William Loney RN Website – biography of Edward Hulton". Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "HMS Dryad at William Loney website". Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8. OCLC 67375475.