HPV vaccines

| |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | human papillomavirus |

| Type | Protein subunit |

| Clinical data | |

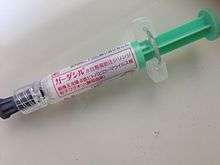

| Trade names | Gardasil, Cervarix |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | injection |

| ATC code | J07BM01 (WHO) J07BM02 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider | none |

| | |

Human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccines are vaccines that prevent infection by certain types of human papillomavirus.[1] Available vaccines protect against either two, four, or nine types of HPV.[1][2] All vaccines protect against at least HPV 16 and 18 that cause the greatest risk of cervical cancer. It is estimated that they may prevent 70% of cervical cancer, 80% of anal cancer, 60% of vaginal cancer, 40% of vulvar cancer, and possibly some mouth cancer.[3][4][5] They additionally prevent some genital warts with the vaccines against 4 and 9 HPV types providing greater protection.[1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends HPV vaccines as part of routine vaccinations in countries that can afford them, along with other prevention measures. The vaccines require two or three doses depending on how old the person is. Vaccinating girls around the ages of nine to thirteen is typically recommended. The vaccines provide protection for at least eight years. Cervical cancer screening is still required following vaccination.[1] Vaccinating a large portion of the population may also benefit the unvaccinated.[6] In those already infected the vaccines do not help.[1]

HPV vaccines are very safe. Pain at the site of injection occurs in about 80% of people. Redness and swelling at the site and fever may also occur. No link to Guillain–Barré syndrome has been found.[1]

The first HPV vaccine became available in 2006. As of 2014, 58 countries include it in their routine vaccinations, at least for girls.[1] They are on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medication recommended for a basic health system.[7] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$47 a dose as of 2014.[8] In the United States it cost more than US$200.[9] Vaccination may be cost effective in the developing world.[10]

Medical uses

HPV vaccines are used to prevent HPV infection and therefore cervical cancer.[1] They are recommended for women who are 9 to 25 years old who have not been exposed to HPV. However, since it is unlikely that a woman will have already contracted all four viruses, and because HPV is primarily sexually transmitted, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended vaccination for women up to 26 years of age.

Since the vaccine only covers some high-risk types of HPV, cervical cancer screening is recommended even after vaccination.[1][11] In the US, the recommendation is for women to receive routine Pap smears beginning at age 21. Additional vaccine candidate research is occurring for next generation products to extend protection against additional HPV types.

Males

HPV vaccines are approved for males in several countries, including Canada, Australia, South Korea, Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Gardasil has been shown to also be effective in preventing genital warts in males.[12][13] On 9 September 2009, an advisory panel recommended that the FDA licence Gardasil in the United States for boys and men ages 9–26 for the prevention of genital warts.[14] Soon after that, the vaccine was approved by the FDA for use in males aged 9 to 26 for prevention of genital warts[12][13] and anal cancer.[15] While Gardasil and Gardasil-9 vaccines have been approved for males, the third HPV vaccine, Cervarix, is not administered to males. Unlike the Gardasil-based vaccines, Cervarix does not protect against genital warts.[16]

On October 25, 2011, an advisory panel for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) voted to recommend that the vaccine should be given to boys ages 11–12. The panel's recommendation is intended to prevent genital warts and anal cancers in males, and possibly prevent head and neck cancer (though the vaccine's effectiveness against head and neck cancers has not yet been proven).[17] The Committee also made the vaccination recommendation for males 13 to 21 years who have not been vaccinated previously or who have not completed the three-dose series.[12][18]

In males, Gardasil may reduce their risk of genital warts and precancerous lesions caused by HPV. This reduction in precancerous lesions might be predicted to reduce the rates of penile and anal cancer in men. Since penile and anal cancers are much less common than cervical cancer, HPV vaccination of young men is likely to be much less cost-effective than for young women.[19]

From a public health point of view, vaccinating men as well as women decreases the virus pool within the population, but is only cost-effective if the uptake in the female population is extremely low.[20] In the United States, the cost per quality-adjusted life year is greater than $100,000 for vaccinating the male population, compared to the less than $50,000 for vaccinating the female population.[20] This assumes a 75% vaccination rate. In early 2013 the two companies who sell the most common vaccines announced a price cut to less than $5 per dose to poor countries, as opposed to $130 per dose in the US.[21]

As with females, the vaccine should be administered before infection with the HPV types covered by the vaccine occurs. Vaccination before adolescence, therefore, makes it more likely that the recipient has not been exposed to HPV.

Gardasil is in particular demand among MSMs, who are at higher risk for genital warts, penile cancer, and anal cancer.[22]

Harald zur Hausen's support for vaccinating boys (so that they will be protected and thereby women) was joined by professors Harald Moi and Ole-Erik Iversen in 2011.[23]

Older women

When Gardasil was first introduced, it was recommended as a prevention for cervical cancer for women that were 25 years old or younger. New evidence suggests that all HPV vaccines are effective in preventing cervical cancer for women up to 45 years of age.[24]

In November 2007, Merck presented new data on Gardasil. In an investigational study, Gardasil reduced the incidence of HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18-related persistent infection and disease in women through age 45. The study evaluated women who had not contracted at least one of the HPV types targeted by the vaccine by the end of the three-dose vaccination series. Merck planned to submit this data before the end of 2007 to the FDA, and to seek an indication for Gardasil for women through age 45.[25]

Efficacy

HPV vaccines have been shown to prevent cervical dysplasia from the high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 and some protection against a few closely related high-risk HPV types.[1] However, there are other high-risk HPV types that are not affected by the vaccines.[26] The protection against HPV 16 and 18 has lasted at least 8 years after vaccination for Gardasil[27] and more than 9 years for Cervarix.[27] It is thought that booster vaccines will not be necessary.[28]

Gardasil also protects against low-risk HPV types 6 and 11, which are much less likely to cause cancer, but do cause genital warts.

A recent analysis of data from a clinical trial of Cervarix found that this vaccine is just as effective at protecting women against persistent HPV 16 and 18 infection in the anus as it is at protecting them from these infections in the cervix. Overall, about 30 percent of cervical cancers will not be prevented by these vaccines. Also, in the case of Gardasil, 10 percent of genital warts will not be prevented by the vaccine. Neither vaccine prevents other sexually transmitted diseases, nor do they treat existing HPV infection or cervical cancer.[29][30]

HPV types 16, 18 and 45 contribute to 94% of cervical adenocarcinoma (cancers originating in the glandular cells of the cervix).[31] While most cervical cancer arises in the squamous cells, adenocarcinomas make up a sizable minority of cancers.[31] Further, Pap smears are not as effective at detecting adenocarcinomas, so where Pap screening programs are in place, a larger proportion of the remaining cancers are adenocarcinomas.[31] Trials suggest that HPV vaccines may also reduce the incidence of adenocarcinoma.[31]

Two doses of the vaccine may work as well as three doses.[32] The CDC recommends two doses in those less than 15 and three doses in those over 15.[33]

A study with 9vHPV, a 9-valent HPV vaccine that protects against HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58, came to the result that the rate of high-grade cervical, vulvar, or vaginal disease was the same as when using a quadrivalent HPV vaccine.[34] A lack of a difference may have been caused by the study design of including women 16 to 26 years of age, who may largely already have been infected with the five additional HPV types that are additionally covered by the 9-valent vaccine.[35]

Public health

The National Cancer Institute states "Widespread vaccination has the potential to reduce cervical cancer deaths around the world by as much as two-thirds if all women were to take the vaccine and if protection turns out to be long-term. In addition, the vaccines can reduce the need for medical care, biopsies, and invasive procedures associated with the follow-up from abnormal Pap tests, thus helping to reduce health care costs and anxieties related to abnormal Pap tests and follow-up procedures."[11]

Current preventive vaccines protect against the two HPV types (16 and 18) that cause about 70% of cervical cancers worldwide.[36] Because of the distribution of HPV types associated with cervical cancer, the vaccines are likely to be most effective in Asia, Europe, and North America.[36] Some other high-risk types cause a larger percentage of cancers in other parts of the world.[36] Vaccines that protect against more of the types common in cancers would prevent more cancers, and be less subject to regional variation.[36] For instance, a vaccine against the seven types most common in cervical cancers (16, 18, 45, 31, 33, 52, 58) would prevent an estimated 87% of cervical cancers worldwide.[36]

Only 41% of women with cervical cancer in the developing world get medical treatment.[37] Therefore, prevention of HPV by vaccination may be a more effective way of lowering the disease burden in developing countries than cervical screening. The European Society of Gynecological Oncology sees the developing world as most likely to benefit from HPV vaccination.[38] However, individuals in many resource-limited nations, Kenya for example, are unable to afford the vaccine.[39]

In more developed countries, populations that do not receive adequate medical care, such as poor or minorities in the United States or parts of Europe also have less access to cervical screening and appropriate treatment, and are similarly more likely to benefit.[31] Comments made by Dr. Diane Harper, a researcher for the HPV vaccines, were interpreted as indicating that in countries where Pap smear screening is common, it will take vaccination of a large proportion of women in order to further reduce cervical cancer rates.[40] She has also encouraged women to continue pap screening after they are vaccinated and to be aware of potential adverse effects.[41]

According to the CDC, as of 2012, use of the HPV vaccine had cut rates of infection with HPV-6, -11, -16 and -18 in half in American teenagers (from 11.5% to 4.3%) and by one third in American women in their early twenties (from 18.5% to 12.1%).[42]

Side effects

While the use of HPV vaccines can help reduce cervical cancer deaths by two thirds around the world,[43] not everyone is eligible for vaccination. There are some factors that exclude people from receiving HPV vaccines. These factors include:[44]

- People with history of immediate hypersensitivity to vaccine components. Patients with a hypersensitivity to yeast should not receive Gardasil since yeast is used in its production.

- People with moderate or severe acute illnesses. This does not completely exclude patients from vaccination, but postpones the time of vaccination until the illness has improved.[45]

Pregnancy

In the Gardasil clinical trials, 1,115 pregnant women received the HPV vaccine. Overall, the proportions of pregnancies with an adverse outcome were comparable in subjects who received Gardasil and subjects who received placebo.[46] However, the clinical trials had a relatively small sample size. Currently, the vaccine is not recommended for pregnant women.[46][47] The long-term effects of the vaccine on fertility are not known, but no effects are anticipated.

The FDA has classified the HPV vaccine as a pregnancy Category B, meaning there is no apparent harm to the fetus in animal studies. HPV vaccines have not been causally related with adverse pregnancy outcomes or adverse effects on the fetus. However, data on vaccination during pregnancy is very limited and vaccination during the pregnancy term should be delayed until more information is available. If a woman is found to be pregnant during the three-dose series of vaccination, the series will be postponed until pregnancy has been completed. While there is no indication for intervention for vaccine dosages administered during pregnancy, patients and health-care providers are encouraged to report exposure to vaccines to the appropriate HPV vaccine pregnancy registry.[44][45][48]

Safety

HPV vaccines are approved for use in over 100 countries, with more than 100 million doses distributed worldwide. Extensive clinical trial and post-marketing safety surveillance data indicate that both Gardasil and Cervarix are well tolerated and safe.[49]

A cohort study of approximately 1 million girls found no evidence supporting associations between exposure to quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine and autoimmune, neurological, and venous thromboembolic adverse events.[50]

Gardasil is a 3-dose (injection) vaccine. As of 8 September 2013 there have been more than 57 million doses distributed in the United States, though it is unknown how many have been administered.[51] There have been 22,000 Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) reports following the vaccination.[52] Ninety-two percent were reports of events considered to be non-serious (e.g., fainting, pain and swelling at the injection site (arm), headache, nausea and fever), and 9 percent were considered to be serious (death, permanent disability, life-threatening illness and hospitalization). There is no proven causal link between the vaccine and serious adverse effects; VAERS reports include any effects whether coincidental or causal. The CDC states: "When evaluating data from VAERS, it is important to note that for any reported event, no cause-and-effect relationship has been established. VAERS receives reports on all potential associations between vaccines and adverse events."[52]

As of 1 September 2009, there have been 44 U.S. reports of death in females after receiving the vaccine.[52] None of the 27 confirmed deaths of women and girls who had taken the vaccine were linked to the vaccine.[52] There is no evidence suggesting that Gardasil causes or raises the risk of Guillain–Barré syndrome. Additionally, there have been rare reports of blood clots forming in the heart, lungs and legs.[52] A 2015 review conducted by the European Medicines Agency's Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee concluded that evidence does not support the idea that HPV vaccination causes complex regional pain syndrome or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.[53]

As of 8 September 2013 the CDC continues to recommend Gardasil vaccination for the prevention of four types of HPV.[52] Merck, the manufacturer of Gardasil, has committed to ongoing research assessing the vaccine's safety.[54]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the FDA, the rate of adverse side effects related to Gardasil immunization in the safety review was consistent with what has been seen in the safety studies carried out before the vaccine was approved and were similar to those seen with other vaccines. However, a higher proportion of syncope (fainting) were seen with Gardasil than are usually seen with other vaccines. The FDA and CDC have reminded health care providers that, to prevent falls and injuries, all vaccine recipients should remain seated or lying down and be closely observed for 15 minutes after vaccination.[30] The HPV vaccination does not appear to reduce the willingness of women to undergo pap tests.[55]

Mechanism of action

The HPV vaccines are based on hollow virus-like particles (VLPs) assembled from recombinant HPV coat proteins. The virus possesses circular double stranded DNA and a viral shell that is composed of 72 capsomeres. Every subunit of the virus is composed of two proteins molecules, L1 and L2. The reason why this virus has the capability to affect the skin and the mucous layers is due to its structure. The primary structures expressed in these areas are E1 and E2, these proteins are responsible for the replication of the virus.[56] E1 is a highly conserved protein in the virus, E1 is in charge of the production of viral copies is also involved in every step of replication process.[56] The second component of this process is E2 ensures that non-specific interaction occurs while interacting with E1.[56] As a result of these proteins working together is assures that numerous amounts of copies are made within the host cell. The structure of the virus is critical because this influence the infection affinity of the virus. Knowing the structure of the virus allowed for the development of an efficient vaccine, such as Gardasil and Cervarix. The vaccines target the two high-risk HPVs, types 16 and 18 that cause the most cervical cancers. Gardasil's proteins are synthesized by the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Its protein makeup allows it to target four types of HPV. Gardasil contains inactive L1 proteins from four different HPV strains: 6, 11, 16, and 18. Each vaccine dose contains 225 µg of aluminum, 9.56 mg of sodium chloride, 0.78 mg of L-histidine, 50 µg of polysorbate 80, 35 µg of sodium borate, and water. The combination of ingredients totals 0.5 mL.[57] Together, these two HPV types currently cause about 70 percent of all cervical cancer.[36] Gardasil also targets HPV types 6 and 11, which together currently cause about 90 percent of all cases of genital warts.[58]

Gardasil and Cervarix are designed to elicit virus-neutralizing antibody responses that prevent initial infection with the HPV types represented in the vaccine. The vaccines have been shown to offer 100 percent protection against the development of cervical pre-cancers and genital warts caused by the HPV types in the vaccine, with few or no side effects. The protective effects of the vaccine are expected to last a minimum of 4.5 years after the initial vaccination.[26]

While the study period was not long enough for cervical cancer to develop, the prevention of these cervical precancerous lesions (or dysplasias) is believed highly likely to result in the prevention of those cancers.[59]

History

The vaccine was first developed by the University of Queensland in Australia and the final form was made by researchers at the University of Queensland, Georgetown University Medical Center, University of Rochester, and the U.S. National Cancer Institute.[60] Researchers Ian Frazer and Jian Zhou at the University of Queensland have been accorded priority under U.S. patent law for the invention of the HPV vaccine's basis, the VLPs.[61] In 2006, the FDA approved the first preventive HPV vaccine, marketed by Merck & Co. under the trade name Gardasil. According to a Merck press release,[62] in the second quarter of 2007, it had been approved in 80 countries, many under fast-track or expedited review. Early in 2007, GlaxoSmithKline filed for approval in the United States for a similar preventive HPV vaccine, known as Cervarix. In June 2007 this vaccine was licensed in Australia, and it was approved in the European Union in September 2007.[63] Cervarix was approved for use in the U.S. in October 2009.[64]

Harald zur Hausen, a German researcher who initially suspected and later helped to prove that genital HPV infection can lead to cervical cancer, was awarded half of the $1.4 million Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work. Verification that cervical cancer is caused by an infectious agent led several other groups (see above) to develop vaccines against HPV strains that cause most cases of cervical cancer. The other half of the award went to Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier, two French virologists, for their part in the discovery of HIV.[65]

zur Hausen went against current dogma and postulated that oncogenic human papilloma virus (HPV) caused cervical cancer.[30] He realized that HPV-DNA could exist in a non-productive state in the tumours, and should be detectable by specific searches for viral DNA.[65] He and others, notably workers at the Pasteur Institute, found HPV to be a heterogeneous family of viruses. Only some HPV types cause cancer.[30]

Harald zur Hausen pursued his idea of HPV for over 10 years by searching for different HPV types. [3] This research was difficult due to the fact that only parts of the viral DNA were integrated into the host genome. He found novel HPV-DNA in cervix cancer biopsies, and thus discovered the new, tumourigenic HPV16 type in 1983. In 1984, he cloned HPV16 and 18 from patients with cervical cancer.[65] The HPV types 16 and 18 were consistently found in about 70% of cervical cancer biopsies throughout the world.[30]

His observation of HPV oncogenic potential in human malignancy provided impetus within the research community to characterize the natural history of HPV infection, and to develop a better understanding of mechanisms of HPV-induced carcinogenesis.[30]

In December 2014, the United States' Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a vaccine called Gardasil 9 to protect females between the ages of 9 and 26 and males between the ages of 9 and 15 against nine strains of HPV.[66] Gardasil 9 protects against infection with the strains covered by the first generation of Gardasil (HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, and HPV-18) and protects against five other HPV strains responsible for 20% of cervical cancers (HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-45, HPV-52, and HPV-58).[66]

Vaccine implementation

In developed countries, the widespread use of cervical "Pap smear" screening programs has reduced the incidence of invasive cervical cancer by 50% or more. Current preventive vaccines reduce but do not eliminate the chance of getting cervical cancer. Therefore, experts recommend that women combine the benefits of both programs by seeking regular Pap smear screening, even after vaccination.[67] The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) has recommended all European teenage girls to be vaccinated; however Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Turkey currently do not have a vaccination program in place.

Africa

With support from the GAVI Alliance, a number of low-income African countries have begun rollout of the HPV vaccine, with others to follow. In 2013 Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Niger, Sierra Leone, and the United Republic of Tanzania begin implementation of the vaccine. In 2014, Rwanda will begin nationwide rollout, and demonstration programs will take place in Mozambique and Zimbabwe.[68]

Australia

In April 2007, Australia became the first country to introduce a government-funded National Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Program to protect young women against HPV infections that can lead to cancers and disease.[69] The National HPV Vaccination Program is listed on the National Immunisation Program (NIP) Schedule and funded under the Immunise Australia Program.[70] The Immunise Australia Program is a joint Australian, State, and Territory Government initiative to increase immunisation rates for vaccine preventable diseases.

The National HPV Vaccination Program for females was made up of two components: an ongoing school-based program for 12- and 13-year-old girls; and a time-limited catch-up program (females aged 14–26 years) delivered through schools, general practices, and community immunization services, which ceased on 31 December 2009.

During 2007–2009, an estimated 83% of females aged 12–17 years received at least one dose of HPV vaccine and 70% completed the 3-dose HPV vaccination course.[69] Latest HPV coverage data on the Immunise Australia website show that by 15 years of age, over 70% of Australian females have received all three doses. This has remained steady since 2009.[71]

Since the National HPV Vaccination Program commenced in 2007, there has been a reduction in HPV-related infections in young women. A study published in The Journal of Infectious Disease in October 2012 found the prevalence of vaccine-preventable HPV types (6, 11, 16 and 18) in Papanicolaou test results of women aged 18–24 years has significantly decreased from 28.7% to 6.7% four years after the introduction of the National HPV Vaccination Program.[69] A 2011 report published found the diagnosis of genital warts (caused by HPV types 6 and 11) had also decreased in young women and men.[72]

In October 2010, the Australian regulatory agency, the Therapeutic Goods Administration, extended the registration of the quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil) to include use in males aged 9 through 26 years of age, for the prevention of external genital lesions and infection with HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18.

In November 2011, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) recommended the extension of the National HPV Vaccination Program to include males. The PBAC made its recommendation on the preventative health benefits that can be achieved, such as a reduction in the incidence of anal and penile cancers and other HPV-related diseases. In addition to the direct benefit to males, it was estimated that routine HPV vaccination of adolescent males would contribute to the reduction of vaccine HPV-type infection and associated disease in women through herd immunity.[73]

On 12 July 2012, the Australian Government announced funding to extend the National HPV Vaccination Program to include males, with implementation commencing in all states and territories in February 2013.[74]

Updated results were reported in 2014.[75]

From February 2013, free HPV vaccine is being provided through school-based programs for:

- males and females aged 12–13 years (ongoing program); and

- males aged between 14–15 years—until the end of the school year in 2014 (catch up program).

Further information is available on the HPV Vaccination Program website at www.australia.gov.au/hpv

Canada

In July 2006, human papillomavirus vaccine against 4 types of HPV was authorized in Canada for females 9 to 26 years. In February 2010, use in males 9 to 26 years of age for prevention of genital warts was authorized.[76]

Currently, all Canadian provinces and territories fund HPV school-based immunization programs for females.[77]

Two provinces have implemented HPV immunization programs for boys, Prince Edward Island and Alberta.[78]

Canada has approved use of Gardasil.[79] Initiating and funding free vaccination programs has been left to individual Province/Territory Governments. In the provinces of Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia,[80] free vaccinations to protect women against HPV were slated to begin in September 2007 and will be offered to girls ages 11–14. Similar vaccination programs are being planned in British Columbia and Quebec.[81][82][83]

China

GSK China announced on July 18th, 2016, that Cervarix (HPV vaccine 16 and 18) had been approved by China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA), therefore became the first approved HPV vaccine in China. Cervarix is registered in China for girls aged 9 to 25, adopting 3-dose program within 6 months. Cervarix is expected to be marketed in China in early 2017.[84]

On the same day, China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) also announced that the import registration application of Human Papillomavirus Absorbed Vaccine (Cervarix), the preventive biological product manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline, had been approved on July 12th, 2016. The approval of this vaccine will provide a brand-new effective method to prevent cervical cancers.[85]

Colombia

The vaccine was introduced in 2012, approved for 9 aged girls.[86][87] The HPV vaccine begins to delivered to girls aged 9 and older and are attending fourth grade of school. Since 2013 the age of coverage was extended to girls in school from grade four who have reached the age of 9 to grade 11th independent of age; and no schooling from age 9–17 years 11 months and 29 days old.[88]

Europe

| Country | Date of introduction | Gender(s) | Target age group | Financed by | Policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 2006 | M/F | 10–12 | Fully financed by national health authorities[89] | |

| Belgium | 2007 | 10–13 | Financed 75% by national health authorities | ||

| Croatia | 20 May 2016 | M\F | 12 | Fully financed by national health authorities 100% | Voluntary immunization for women not yet sexually active |

| Denmark[90] | 1 January 2009 | F | 12 | Fully financed by national health authorities | Part of the Danish Childhood Vaccination program |

| France[91] | 11 July 2007 | F | 14–23 | Financed 65% by national health authorities | Voluntary immunization for women not yet sexually active |

| Germany[92] | 26 March 2007 | ||||

| Greece[93][94] | 12 February 2007 | F | 12–26 | Fully financed by national health authorities | Mandatory for all girls entering 7th grade |

| Hungary[95] | 2014 | F | 12 | Fully financed by national health authorities. In addition subsidised by local councils for 13- and 14-year-olds. | |

| Iceland | 2011 | 12 | Fully financed by national health authorities | ||

| Ireland | 2008 | 12–13 | Fully financed by national health authorities | ||

| Italy[92] | 26 March 2007 | F | 12 | ||

| Latvia | 2009 | 12 | Fully financed by national health authorities | ||

| Luxembourg | 2008 | 12 | Fully financed by national health authorities | ||

| Macedonia | 2009 | F | 12 | Fully financed by national health authorities | Mandatory; part of the national immunization schedule |

| Netherlands | 2009 | F | 12–13 | Fully financed by national health authorities | |

| Norway | 2009 | F | 12–13 | Part of the national immunization program | |

| Portugal | 2007 | 13 | Fully financed by national health authorities | ||

| Romania | November 2008 | F | 10–11 | ||

| Slovenia | 2009 | 11–12 | Fully financed by national health authorities | ||

| Spain | 2007 | 11–14 | Fully financed by national health authorities | ||

| Sweden[96] | 1 January 2010 | F | 10–12 | ||

| Switzerland | 2008 | 11–14 | Fully financed by national health authorities | ||

| UK | September 2008 | M/F | M:9–15 F:9–26 |

Fully financed by national health authorities for girls only |

Israel

Introduced in 2012. Target age group 13–14. Fully financed by national health authorities only for this age group. For the year 2013–2014, girls in the eighth grade may get the vaccine free of charge only in school, and not in Ministry of Health offices or clinics. Girls in the ninth grade may receive the vaccine free of charge only at Ministry of Health offices, and not in schools or clinics.[97] Religious and conservative groups are expected to refuse the vaccination.[98]

Japan

Introduced in 2010, widely available only since April 2013. Fully financed by national health authorities. In June 2013, however, Japan's Vaccine Adverse Reactions Review Committee (VARRC) suspended recommendation of the vaccine due to fears of adverse events. This directive has been criticized by researchers at the University of Tokyo as a failure of governance since the decision was taken without presentation of adequate scientific evidence.[99]

Kenya

Both Cervarix and Gardasil are approved for use within Kenya by the Pharmacy and Poisons Board. However, at a cost of 20,000 Kenyan shillings, which is more than the average annual income for a family, the director of health promotion in the Ministry of Health, Nicholas Muraguri, states that many Kenyans are unable to afford the vaccine.[39]

Laos

In 2013 Laos began implementation of the HPV vaccine, with the assistance of the Gavi Alliance.[68]

Mexico

The vaccine was introduced in 2008 to 5% of the population. This percentage of the population had the lowest development index which correlates with the highest incidence of cervical cancer.[100] The HPV vaccine is delivered to girls 12 – 16 years old following the 0-2-6 dosing schedule. By 2009 Mexico had expanded the vaccine use to girls, 9–12 years of age, the dosing schedule in this group was different, the time elapsed between the first and second dose was six months and the third dose 60 months later.[101] In 2011 Mexico approved a nationwide use of HPV vaccination program to include vaccination of all 9-year-old girls.[101]

New Zealand

The publicly funded New Zealand HPV Immunisation Programme began on 1 September 2008. Gardasil is available free for New Zealand girls, usually through a school-based program in Year 8 (approximately age 12), but also through general practices and some family planning clinics. While it is recommended at age 12, it is free for young women before their 20th birthday. Over 200,000 New Zealand girls and young women have received HPV immunization as at November 2015, around 60% of eligible girls.[102]

Panama

The vaccine was added to the national immunization program in 2008, to target girls in the population aged 10.[100] The vaccine is being administer by clinics and schools.[101]

South Africa

Cervical cancer represents the most common cause of cancer-related deaths—more than 3,000 deaths per year—among women in South Africa because of high HIV prevalence, making introduction of the vaccine highly desirable.[103] A Papanicolaou test program was established in 2000 to help screen for cervical cancer, but since this program has not been implemented widely, vaccination would offer more efficient form of prevention.[104] In May 2013 the Minister of Health of South Africa, Aaron Motsoaledi, announced the government would provide free HPV vaccines for girls aged 9 and 10 in the poorest 80% of schools starting in February 2014 and the fifth quintile later on.[105] South Africa will be the first African country with an immunisation schedule that includes vaccines to protect people from HPV infection, but because the effectiveness of the vaccines in women who later become infected with HIV is not yet fully understood, it is difficult to assess how cost-effective the vaccine will be. Negotiations are currently underway for more affordable HPV vaccines since they are up to 10 times more expensive than others already included in the immunization schedule.[103][105]

South Korea

On July 27, 2007, South Korean government approved Gardasil for use in girls and women aged 9 to 26 and boys aged 9 to 15.[106] Approval for use in boys was based on safety and immunogenicity but not efficacy.

Since 2016, HPV vaccination has been part of the National Immunization Program, offered free of charge to all children under 12 in South Korea, with costs fully covered by the Korean government.[107]

For 2016 only, Korean girls born between 1 January 2003 to 31 December 2004 are also eligible to receive the free shots as a limited time offer. From 2017, the free shots will be available to those under 12 only.[108]

Trinidad and Tobago

Introduced in 2013. Target Group 9–26. Fully financed by national health authorities. Administration in schools currently suspended owing to objections and concerns raised by the Catholic Board, but fully available in local health centers.

United Kingdom

In the UK the vaccine is licensed for girls aged 9 to 15, for women aged 16 to 26, and for boys aged 9–15.[109]

HPV vaccination with Cervarix was introduced into the national immunization program in September 2008, for girls aged 12–13 across the UK. A two-year catch-up campaign started in Autumn 2009 to vaccinate all girls up to 18 years of age. Catch up vaccination will be offered to:

- girls aged between 16 and 18 from autumn 2009, and

- girls aged between 15 and 17 from autumn 2010.

By the end of the catch-up campaign, all girls under 18 will have been offered the HPV vaccine.

In September 2012, Gardasil replaced Cervarix as the HPV vaccination of choice due to its added protection against genital warts.

It will be many years before the vaccination program has an effect on cervical cancer incidence so women are advised to continue accepting their invitations for cervical screening.[110]

United States

Adoption

As of late 2007, about one quarter of US females age 13–17 years had received at least one of the three HPV shots.[111] By 2014, the proportion of such females receiving a vaccination had risen to 38%.[112] The government began recommending vaccination for boys in 2011; by 2014, the vaccination rate among boys (at least one dose) had reached 35%.[112]

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), getting as many girls vaccinated as early and as quickly as possible will reduce the cases of cervical cancer among middle-aged women in 30 to 40 years and reduce the transmission of this highly communicable infection. Barriers include the limited understanding by many people that HPV causes cervical cancer, the difficulty of getting pre-teens and teens into the doctor's office to get a shot, and the high cost of the vaccine ($120/dose, $360 total for the three required doses, plus the cost of doctor visits).[29][113] Community-based interventions can increase the uptake of HPV vaccination among adolescents.[114]

A survey was conducted in 2009 to gather information about knowledge and adoption of the HPV vaccine. Thirty percent of 13- to 17-year-olds and 9% of 18- to 26-year-olds out of the total 1,011 young women surveyed reported receipt of at least one HPV injection. Knowledge about HPV varied; however, 5% or fewer subjects believed that the HPV vaccine precluded the need for regular cervical cancer screening or safe-sex practices. Few girls and young women overestimate the protection provided by the vaccine. Despite moderate uptake, many females at risk of acquiring HPV have not yet received the vaccine.[115] For example, young black women are less likely to receive HPV vaccines compared to young white women. Additionally, young women of all races and ethnicities without health insurance are less likely to initiate vaccine uptake.[116]

Since the approval of Gardasil in 2006 and despite low vaccine uptake, prevalence of HPV among teenagers aged 14–19 has been cut in half with an 88% reduction among vaccinated women. No decline in prevalence was observed in other age groups, indicating the vaccine to have been responsible for the sharp decline in cases. The drop in number of infections is expected to in turn lead to a decline in cervical and other HPV-related cancers in the future.[117][118]

Legislation

Shortly after the first HPV vaccine was approved, bills to include the vaccine among those that are mandatory for school attendance were introduced in many states.[119] Only two such bills passed (in Virginia and Washington DC) during the first four years after vaccine introduction.[119] Mandates have been effective at increasing uptake of other vaccines, such as mumps, measles, rubella, and hepatitis B (which is also sexually transmitted).[113] However most such efforts developed for five or more years after vaccine release, while financing and supply were arranged, further safety data was gathered, and education efforts increased understanding, before mandates were considered.[119] Most public policies including school mandates have not been effective in promoting vaccination while receiving a recommendation from a physician increased the probability of vaccination.[120]

State-by-State

The National Conference of State Legislatures periodically issues summaries of HPV vaccine related legislation.[121]

Almost all pieces of legislation currently pending in the states that would make the vaccine mandatory for school entrance have an "opt-out" policy.[121]

In July, 2015, Rhode Island added an HPV vaccine requirement for admittance into public school. This mandate requires all students entering the 7th grade to receive one dose of the HPV vaccine starting in September, 2015.[122][123] No legislative action was required by the Rhode Island Department of Health to add new vaccine mandates. Rhode Island is the first state to mandate the vaccine for both male and female 7th graders.[124]

Other states are also preparing bills to handle issuing the HPV Vaccine.[121]

| State | Proposal | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | HB 42 would allow parents the option of immunizing female students entering the sixth grade, and requires the Department of Health and Senior Services to directly mail age appropriate information to parents or guardians to those students regarding the connection between HPV and cervical cancer and the availability of the immunization. | Passed |

| Alaska | Voluntary vaccination program | Passed |

| Florida | SB 1116 Would require the Department of Health to adopt a rule adding HPV/cervical cancer to the list of communicable diseases for which immunizations are recommended; requires that schools provide the parents or guardians of certain public school students information regarding the disease and the availability of a vaccine; requires the department to prescribe the required information. | Not passed |

| Georgia | HB 736 Would require public Schools to provide parents or guardians of sixth grade female students information concerning the infection and the immunization against the human papillomavirus. | |

| Hawaii | HCR 71 Would request the Department of Health to make human papillomavirus immunization available to indigent patients and through the teen VAX program, and urging insurers to offer coverage for human papillomavirus immunization to female policyholders eleven to twenty-six years of age. | Not Passed |

| Iowa | SSB 3097 Would create a study bill for a HPV public awareness program and make appropriations for the public awareness program, provision of vaccinations, and cervical cancer screenings. | In committee |

| Kansas | HR 6019 Resolution would urge the FDA to use caution in approving new vaccines such as Gardasil which has had a number of health problems including some deaths associated with the use of this vaccine. | In committee |

| Kentucky | HR 80 Would urge females ages 9 to 26 and males ages 11 to 26 to obtain the Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and all citizens to become more knowledgeable about the benefits of HPV vaccination. | Passed |

| Maryland | HB 411 Would require the Statewide Advisory Commission on Immunizations to study the safety of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine; requires the Commission to include specified components in the study, make recommendations, and report the results of its study. | Passed |

| Minnesota | HF 1758 Would require the commissioner of health to prepare informational materials on vaccines including the HPV vaccines and encourages public and private schools with students in grades 6-12 to provide this information to parents in a cost-effective and programmatically effective manner. (Introduced 3/16/09) | |

| Michigan | SB 1062 and SB 1063 Each would require health insurers to provide coverage for human papillomavirus screenings for cervical cancer. | In committee |

| Mississippi | HB 1512 Would require health benefit plans to cover HPV screenings. | Not Passed |

| Missouri | HB 1935 Would require health insurers to provide coverage for human papillomavirus screenings for cervical cancer. | In committee |

| New Jersey | S 1163 Would require health insurers and State Health Benefits Program and SEHBP to provide coverage for screening for cervical cancer, including testing for HPV. (Sent to Committee 1/23/12)

A 2185 Would require insurers and State health care coverage programs to cover cost of HPV vaccine. |

In committee |

| New York | SB 98 (same as AB 2360) Would encourage voluntary, informed vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV). (Amended in Senate Committee on Health 1/5/12)

AB 699 Would require immunization against HPV for children born after Jan. 1, 1996. (Sent to Assembly Committee on Health 1/5/11) AB 1946 Would require insurance companies to provide coverage for the vaccine against human papilloma virus. (Sent to committee 1/12/11) AB 2360 Would encourage voluntary, informed vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) for school-aged children and their parents or guardians. (Sent to committee 1/18/11) SB 4708 Would require insurance companies to cover HPV vaccine. |

In committee |

| Oregon | HB 2794 Would require health benefit plans to provide coverage of human papillomavirus vaccine for female beneficiaries who are 11 years of age or older. | Passed |

| Pennsylvania | HB 524 Would require health insurance policies to provide coverage for vaccinations for human papilloma virus. | In committee |

| South Carolina | HB 4497 Would enact the Cervical Cancer Prevention Act and allow the Department of Health and Environmental Control to offer the option of an HPV vaccine series to female students entering the seventh grade at the request of their parent or guardian pending state and federal funding. | In committee |

| Texas | HB 2220 Would allow the Executive Commissioner of the Health and Human Services Commission to require immunization against human papillomavirus or other immunizations for a person's admission to elementary or secondary school. | In committee |

| Virginia | HB 1419 Would repeal the HPV vaccination requirement for female children. (Passed House 1/21/11, Indefinitely passed by the Senate Committee 2/17/11)

HB 65 Would repeal the requirement for children to receive the HPV vaccination for school attendance. (Left in committee 2/14/12) HB 824 Would require that the Commonwealth shall assume liability for any injury resulting from administration of the human papillomavirus vaccine. HB 1112 Would eliminate the requirement for vaccination against human papillomavirus for female children. |

Passed House and sent to Senate |

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures

Immigrants

Between July 2008 and December 2009, proof of the first of three doses of HPV Gardasil vaccine was required for women ages 11–26 intending to legally enter the United States. This requirement stirred controversy because of the cost of the vaccine, and because all the other vaccines so required prevent diseases which are spread by respiratory route and considered highly contagious.[125] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention repealed all HPV vaccination directives for immigrants effective December 14, 2009.[126]

Coverage

Measures have been considered including requiring insurers to cover HPV vaccination, and funding HPV vaccines for those without insurance. The cost of the HPV vaccines for females under 18 who are uninsured is covered under the federal Vaccines for Children Program.[127] As of 23 September 2010, vaccines are required to be covered by insurers under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. HPV vaccines specifically are to be covered at no charge for women, including those who are pregnant or nursing.[128]

Medicaid covers HPV vaccination in accordance with the ACIP recommendations, and immunizations are a mandatory service under Medicaid for eligible individuals under age 21. [1] In addition, Medicaid includes the Vaccines for Children Program. [1] This program provides immunization services for children 18 and under who are Medicaid eligible, uninsured, underinsured, receiving immunizations through a Federally Qualified Health Center or Rural Health Clinic, or are Native American or Alaska Native.[1]

The vaccine manufacturers also offer help for people who cannot afford HPV vaccination. GlaxoSmithKline's Vaccines Access Program[129] provides Cervarix[130] free of charge 1-877-VACC-911[131] to low income women, ages 19 to 25, who do not have insurance.[132] Merck's Vaccine Patient Assistance Program 1-800-293-3881[133] provides Gardasil free to low income women and men, ages 19 to 26, who do not have insurance, including immigrants who are legal residents.[134]

Opposition in the United States

Insurance companies

There has been significant opposition from health insurance companies to covering the cost of the vaccine ($360).[135][136][137]

Religious and conservative groups

Opposition due to the safety of the vaccine has been addressed through studies, leaving opposition focused on the sexual implications of the vaccine to remain. Conservative[138] groups in the U.S. have publicly opposed the concept of making HPV vaccination mandatory for pre-adolescent girls, asserting that making the vaccine mandatory is a violation of parental rights. They also say that it will lead to early sexual activity, giving a false sense of immunity to sexually transmitted disease. (See Peltzman effect) Both the Family Research Council and the group Focus on the Family support widespread (universal) availability of HPV vaccines but oppose mandatory HPV vaccinations for entry to public school.[139][140][141][142] Parents also express confusion over recent mandates for entry to public school pointing out that HPV is transmitted through sexual contact, not through attending school with other children.[143]

Conservative groups are concerned children will see the vaccine as a safeguard against STDs and will have sex sooner than they would without the vaccine while failing to use contraceptives.[143] However; Many organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics disagree with the argument that the vaccine increases sexual activity among teens.[144] Dr. Christine Peterson, director of the University of Virginia's Gynecology Clinic, said "The presence of seat belts in cars doesn't cause people to drive less safely. The presence of a vaccine in a person's body doesn't cause them to engage in risk-taking behavior they would not otherwise engage in."[145][146]

Parental opposition

Many parents opposed to providing the HPV vaccine to their pre-teens agree the vaccine is safe and effective, but find talking to their children about sex uncomfortable. Dr. Elizabeth Lange, of Waterman Pediatrics in Providence, RI, addresses this concern by emphasizing what the vaccine is doing for the child. Dr. Lange suggests parents should focus on the cancer prevention aspect without being distracted by words like 'sexually transmitted'. Everyone wants cancer prevention, yet here parents are denying their children a form of protection due to the nature of the cancer—Lagne suggests that this much controversy would not surround a breast cancer or colon cancer vaccine. The HPV vaccine is suggested for 11-year-olds because it should be administered before possible exposure to HPV, yes, but also because the immune system has the highest response for creating antibodies around this age. Dr. Lange also emphasized the studies showing that the HPV vaccine does not cause children to be more promiscuous than they would be without the vaccine.[143]

Controversy over the HPV vaccine remains present in the media. Parents in Rhode Island have created a Facebook group called "Rhode Islanders Against Mandated HPV Vaccinations" in response to Rhode Island's mandate that males and females entering the 7th grade, as of September 2015, be vaccinated for HPV before attending public school.[143]

Physician impact

The effectiveness of a physician's recommendation for the HPV vaccine also contributes to low vaccination rates and controversy surrounding the vaccine. A 2015 study of national physician communication and support for the HPV vaccine found physicians routinely recommend HPV vaccines less strongly than they recommend Tdap or meningitis vaccines, find the discussion about HPV to be long and burdensome, and discuss the HPV vaccine last, after all other vaccines. Researchers suggest these factors discourage patients and parents from setting up timely HPV vaccines. In order to increase vaccination rates, this issue must be addressed and physicians should be better trained to handle discussing the importance of the HPV vaccine with patients and their families.[147]

Research

There are high-risk HPV types, that are not affected by available vaccines.[26] Ongoing research is focused on the development of HPV vaccines that will offer protection against a broader range of HPV types. One such method is a vaccine based on the minor capsid protein L2, which is highly conserved across HPV genotypes.[148] Efforts for this have included boosting the immunogenicity of L2 by linking together short amino acid sequences of L2 from different oncogenic HPV types or by displaying L2 peptides on a more immunogenic carrier.[149] [150] There is also substantial research interest in the development of therapeutic vaccines, which seek to elicit immune responses against established HPV infections and HPV-induced cancers.[151]

Therapeutic vaccines

In addition to preventive vaccines, such as Gardasil and Cervarix, laboratory research and several human clinical trials are focused on the development of therapeutic HPV vaccines. In general, these vaccines focus on the main HPV oncogenes, E6 and E7. Since expression of E6 and E7 is required for promoting the growth of cervical cancer cells (and cells within warts), it is hoped that immune responses against the two oncogenes might eradicate established tumors.[152]

There is a working therapeutic HPV vaccine that has been clinically tried in Mexico. Developed by Ricardo Rosales. It has gone through 3 clinical trials and has been approved for use by the Mexican government. It is a MVA based vaccine with an e2 bovine protein added in. It has been shown to completely eliminate HPV to the point that patients test negative for the presence of HPV in blood tests. The vaccine is officially called the MEL-1 vaccine but also known as the MVA-E2 vaccine. The vaccine has proven to be safe as far as is known there have been no side effects or other documented issues. The vaccine is administered locally to the infected areas and also given in the arm if the infection is mild. In a study it has been suggested that an immunogenic peptide pool containing epitopes that can be effective against all the high-risk HPV strains circulating globally and 14 conserved immunogenic peptide fragments from 4 early proteins (E1, E2, E6 and E7) of 16 high-risk HPV types providing CD8+ responses.[153][154][155][156][157]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, October 2014." (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 43 (89): 465–492. Oct 24, 2014. PMID 25346960.

- ↑ Kash, N; Lee, MA; Kollipara, R; Downing, C; Guidry, J; Tyring, SK (3 April 2015). "Safety and Efficacy Data on Vaccines and Immunization to Human Papillomavirus.". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 4 (4): 614–33. doi:10.3390/jcm4040614. PMID 26239350.

- ↑ De Vuyst, H; Clifford, GM; Nascimento, MC; Madeleine, MM; Franceschi, S (1 April 2009). "Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis.". International Journal of Cancer. 124 (7): 1626–36. doi:10.1002/ijc.24116. PMID 19115209.

- ↑ Takes, RP; Wierzbicka, M; D'Souza, G; Jackowska, J; Silver, CE; Rodrigo, JP; Dikkers, FG; Olsen, KD; Rinaldo, A; Brakenhoff, RH; Ferlito, A (December 2015). "HPV vaccination to prevent oropharyngeal carcinoma: What can be learned from anogenital vaccination programs?". Oral Oncology. 51 (12): 1057–60. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.10.011. PMID 26520047.

- ↑ Thaxton, L; Waxman, AG (May 2015). "Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015.". Medical Clinics of North America. 99 (3): 469–77. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003. PMID 25841595.

- ↑ Saville, AM (30 November 2015). "Cervical cancer prevention in Australia: Planning for the future.". Cancer Cytopathology. doi:10.1002/cncy.21643. PMID 26619381.

- ↑ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Vaccine, Hpv". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 314. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ Fesenfeld, M; Hutubessy, R; Jit, M (20 August 2013). "Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination in low and middle income countries: a systematic review.". Vaccine. 31 (37): 3786–804. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.060. PMID 23830973.

- 1 2 "Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines: Q & A". Fact Sheets: Risk Factors and Possible Causes. National Cancer Institute (NCI). 2009-10-22. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- 1 2 3 "FDA Approves New Indication for Gardasil to Prevent Genital Warts in Men and Boys" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 2009-10-30.

- 1 2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010). "FDA licensure of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4, Gardasil) for use in males and guidance from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 59 (20): 630–632. PMID 20508594.

- ↑ Castle PE, Scarinci I (2009). "Should HPV vaccine be given to men?". BMJ. 339 (7726): 872–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4127. PMID 19815585.

- ↑ "FDA: Gardasil approved to prevent anal cancer". 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Vaccine Information Statement | HPV Cervarix | VIS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ↑ Rettner, Rachael. "Boys Should Get HPV Vaccine Too, CDC Says". LiveScience. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ↑ "CDC panel recommends HPV vaccine for boys, too". October 26, 2011.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Elisabeth (2008-08-19). "Drug Makers' Push Leads to Cancer Vaccines' Fast Rise". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

Said Dr. Raffle, the British cervical cancer specialist: "Oh, dear. If we give it to boys, then all pretense of scientific worth and cost analysis goes out the window."

- 1 2 Kim, J. J.; Goldie, S. J. (October 2009). "Cost effectiveness analysis of including boys in a human papillomavirus vaccination programme in the United States". British Medical Journal. 339 (7726): 909–19. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3884. PMC 2759438

. PMID 19815582. Retrieved 2009-10-30.

. PMID 19815582. Retrieved 2009-10-30. - ↑ "Cancer Vaccines Get a Price Cut in Poor Nations". New York Times. 5 May 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ↑ "Gay men seeking HPV vaccine". Cancer Research UK. 23 February 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ↑ Moi, Harald; Iversen, Ole-Erik (2011-12-17). "Gi guttene jentevaksine". Dagens Næringsliv (in Norwegian). p. 32.

Zur Haussen, som fikk Nobelprisen i 2009 for sin HPV-forskning, har lenge argumentert for vaksinasjon av gutter, både som egen beskyttelse og beskyttelse av kvinner.

- ↑ "HPV Vaccine Update". Your Cancer Today. 2007-12-11.

- ↑ 5 November 2007, New Data Presented on GARDASIL, Merck's Cervical Cancer Vaccine, in Women Through Age 45. Retrieved through web archive on February 23, 2009

- 1 2 3 Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM (April 2006). "Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial". Lancet. 367 (9518): 1247–55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68439-0. PMID 16631880.

- 1 2 De Vincenzo, Rosa; et al. (3 December 2014). "Long-term efficacy and safety of human papillomavirus vaccination". Int. J. Women's Health. 6: 999–1010. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S50365. PMC 4262378

. PMID 25587221.

. PMID 25587221. - ↑ "Committee opinion no. 467: human papillomavirus vaccination". Obstet. Gynecol. 116 (3): 800–3. September 2010. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f680c8. PMID 20733476.

- 1 2 Markowitz, L. E.; Dunne, E. F.; Saraiya, M.; Lawson, H. W.; Chesson, H.; Unger, E. R.; Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC); Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) (2007). "Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 56 (RR-2): 1–24. PMID 17380109.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "HPV Vaccines". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2010-10-15. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 |Tay, S. K. (2012). "Cervical cancer in the human papillomavirus vaccination era". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 24 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32834daed9. PMID 22123221.

- ↑ "Comparison of two dose and three dose human papillomavirus vaccine schedules: cost effectiveness analysis based on transmission model". BMJ. 350: g7584. 7 January 2015. doi:10.1136/bmj.g7584.

- ↑ "MEETING OF THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON IMMUNIZATION PRACTICES (ACIP)" (PDF). 14 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ↑ "A 9-Valent HPV Vaccine against Infection and Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Women". N. Engl. J. Med. 372: 711–723. 2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1405044. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ Schuchat, Anne (2015). "HPV "Coverage"". N. Engl. J. Med. 372: 775–776. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1415742.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Muñoz N, Bosch FX, Castellsagué X, Díaz M, de Sanjose S, Hammouda D, Shah KV, Meijer CJ (2004-08-20). "Against which human papillomavirus types shall we vaccinate and screen? The international perspective". Int. J. Cancer. 111 (2): 278–85. doi:10.1002/ijc.20244. PMID 15197783.

- ↑ Wittet S.; Tsu V. (2008). "Cervical cancer prevention and the Millennium Development Goals". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86 (6): 488–90. doi:10.2471/BLT.07.050450. PMC 2647477

. PMID 18568279.

. PMID 18568279. - ↑ "ESGO Statement on Cervical Cancer Vaccination" (PDF). ESGO. 2007.

- 1 2 "Cervarix Marketing in Kenya". Medical News Today. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ Gardasil Researcher Speaks Out, Sharyl Attkisson, CBS News, August 19, 2009

- ↑ Yerman, M. G. (28 December 2009). "An Interview with Dr. Diane M. Harper, HPV Expert". Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ↑ Haelle, Tara (February 23, 2016). "HPV Infection Rates Plummet In Young Women Due To Vaccine". Forbes. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines".

- 1 2 "HPV Vaccine Information for Clinicians—Fact Sheet". CDC.

- 1 2 "Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Recommendations" (PDF). FDA.

- 1 2 Merck Pregnancy Registries—GARDASIL

- ↑ "Who Should NOT Get Vaccinated with these Vaccines?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ↑ "HPV Vaccine and Pregnancy". eMedTV.

- ↑ "Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines for Australians" (PDF). National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance Factsheet. March 2013.

- ↑ Arnheim-Dahlstrom, L.; Pasternak, B.; Svanström, H.; Sparén, P.; Hviid, A. (2013). "Autoimmune, neurological, and venous thromboembolic adverse events after immunisation of adolescent girls with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in Denmark and Sweden: Cohort study". BMJ. 347: f5906. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5906. PMC 3805482

. PMID 24108159.

. PMID 24108159. - ↑ "GARDASIL®, Merck's HPV Vaccine, Available to Developing Countries through UNICEF Tender". BusinessWire. May 9, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Reports of Health Concerns Following HPV Vaccination". Vaccine Safety. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). November 5, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Review concludes evidence does not support that HPV vaccines cause CRPS or POTS" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 5 November 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ "Information from FDA and CDC on Gardasil and its Safety". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2008-07-22. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- ↑ Moghtaderi, Ali; Dor, Avi (2016-08-01). "Immunization and Moral Hazard: The HPV Vaccine and Uptake of Cancer Screening". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- 1 2 3 Arteaga, Arkaitz. "The Shape and Structure of hpv". Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "leftside". Ciitn.missouri.edu. 2007-01-22. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ↑ Lowy DR, Schiller JT (May 2006). "Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 116 (5): 1167–73. doi:10.1172/JCI28607. PMC 1451224

. PMID 16670757.

. PMID 16670757. - ↑ "FDA Licenses New Vaccine for Prevention of Cervical Cancer and Other Diseases in Females Caused by Human Papillomavirus". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2006-06-08. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- ↑ McNeil C (April 2006). "Who invented the VLP cervical cancer vaccines?". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 98 (7): 433. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj144. PMID 16595773.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 7,476,389, titled "Papilloma Virus Vaccines", was granted to co-inventors Ian Frazer and Jian Zhou (Zhou posthumously) on January 13, 2009. Its U.S. application was filed on January 19, 1994, but claimed priority under a July 20, 1992, PTC filing to the date of an initial [AU] Australian patent application filed on July 19, 1991.

- ↑ Merck Reports Double-Digit Earnings-Per-Share Growth for Second Quarter 2007

- ↑ "Glaxo prepares to launch Cervarix after EU okay". Reuters. 2007-09-24. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ "October 16, 2009 Approval Letter—Cervarix". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). October 16, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- 1 2 3 "The Genital HPV Infection Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2009-11-24. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- 1 2 "FDA approves Gardasil 9 for prevention of certain cancers caused by five additional types of HPV" (press release). 10 December 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ↑ Cutts FT, Franceschi S, Goldie S (2007). "Human papillomavirus and HPV vaccines: a review". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 85 (9): 719–26. doi:10.2471/BLT.06.038414. PMC 2636411

. PMID 18026629.

. PMID 18026629. - 1 2 Professor Ian Frazercreator of the HPV vaccine. "Human papillomavirus vaccine - New and underused vaccines support - Types of support". GAVI Alliance. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- 1 2 3 Tabrizi S. Brotherton J. Kaldor J et al. Fall in Human Papillomavirus Prevalence Following a National Vaccination Program. Journal of Infectious Diseases. October 24, 2012.

- ↑ Immunise Australia: Information about the HPV immunisation program

- ↑ Immunise Australia HPV.

- ↑ 2011 Annual Surveillance Report of HIV, viral hepatitis, STIs. (page 28)

- ↑ Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Recommendations.

- ↑ Minister Plibersek announces HPV vaccination for boys.

- ↑ Tabrizi, Sepehr N; Brotherton, Julia M L; Kaldor, John M; Skinner, S Rachel; Liu, Bette; Bateson, Deborah; McNamee, Kathleen; Garefalakis, Maria; Phillips, Samuel; Cummins, Eleanor; Malloy, Michael; Garland, Suzanne M (October 2014). "Assessment of herd immunity and cross-protection after a human papillomavirus vaccination programme in Australia: a repeat cross-sectional study". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 14 (10): 958–966. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70841-2. PMID 25107680. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ National Advisory Committee on Immunization. (2012). Update On Human Papillomavirus Vaccines. In Public Health Agency of Canada (Ed.), Canada Communicable Disease Report (Vol. 37, pp. 1-62)

- ↑ Canadian Immunization Committee. Recommendations for human papillomavirus immunization programs. Canada Communicable Disease Report. 2014;40(8). Public Health Agency of Canada. Publicly Funded Immunization Programs in Canada. 2014; http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/ptimprog-progimpt/table-1-eng.php - fn_2, Bonanni P, Bechini A, Donato R, et al. Human papilloma virus vaccination: impact and recommendations across the world. Therapeutic Advances in Vaccines. 2014.

- ↑ Public Health Agency of Canada. Publicly Funded Immunization Programs in Canada. 2014; http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/ptimprog-progimpt/table-1-eng.php - fn_2.

- ↑ Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Prevention and HPV Vaccine: Questions and Answers

- ↑ HPV Immunization Launched

- ↑ "McGuinty Government Launches Life-Saving HPV Immunization Program:". Premier of Ontario. 2007-08-02. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ "HPV Immunization Launched". Province of Nova Scotia. 2007-06-20. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ "British Columbia To Launch Program To Provide HPV Vaccine to Sixth-Grade Girls Next Fall if Approved, Official Says". Kaiser Daily Women's Health Policy. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ GSK announces Cervarix approved in China to help protect women from cervical cancer

- ↑ CFDA approved Human Papillomavirus Absorbed Vaccine with the market authorization

- ↑ Carvajal (4 September 2012). "Girón ya está vacunando contra el papiloma humano". Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "Vacuna contra el Papiloma Humano será gratuita". Caracol Radio (Actualidad). Prisa Radio. 3 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "ABC VPH vaccine". www.minsalud.gov.co. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "Impfkalender für Schulkinder". Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ↑ "HPV vaccination: Coverage". National Institute for Health Data and Disease Control. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Cancer of the cervix: reimbursement of Gardasil" (in French). 17 July 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- 1 2 Fagbire, O. J. (26 March 2007). "Gardasil, Merck HPV Vaccine, Gets German And Italian Approval For Girls". Vaccine Rx. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ Karakitsos, P. (7 March 2008). "Vaccination against HPV in Greece" (in Greek). Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "The vaccine against cervical cancer and Cervarix vs Gardasil" (in Greek). 12 February 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ antsz.hu

- ↑ "Information om det allmänna barnvaccinationsprogrammet" (in Swedish). Smittskyddsinstitutet. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ health.gov.il

- ↑ Siegel, Judy. "Health Ministry decides to offer free HPV vaccine to 13-year-old girls | JPost | Israel News". JPost. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ↑ Gilmour, S.; Kanda, M.; Kusumi, E.; Tanimoto, T.; Kami, M.; Shibuya, K. (2013). "HPV vaccination programme in Japan". The Lancet. 382 (9894): 768. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61831-0.

- 1 2 "New technologies for cervical cancer prevention: from scientific evidence to program planning.". Pan American Health Organization. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- 1 2 3 "Progress Toward Implementation of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination—the Americas, 2006–2010". Center for Disease and Control Prevention. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ↑ [http://www.health.govt.nz/news-media/news-items/hpv-vaccination-safety>]

- 1 2 Green, A. (7 June 2013). "Life saving cancer vaccine will be difficult to implement". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ↑ Botha, M. H.; Dochez, C. (2012). "Introducing human papillomavirus vaccines into the health system in South Africa". Vaccine. Elsevier Ltd. 30 (Suppl 3): C28–34. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.032. PMID 22939017.

- 1 2 SAPA (15 May 2013). "Schoolgirls to get cancer vaccine". ioL News. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ↑ "가다실 제품 허가 공지". 2007-06-27. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ↑ http://news.kukinews.com/article/view.asp?arcid=0010258599&code=46111501&cp=nv

- ↑ http://www.rapportian.com/n_news/news/view.html?no=26458

- ↑ Roberts, Michelle (2007-02-23). "Gay men seek 'female cancer' jab". BBC.

- ↑ "NHS Cervical Screening Program". Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ "1 in 4 US teen girls got cervical cancer shot". USA Today. Associated Press. 9 October 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- 1 2 "More US Girls Now Getting Cervical Cancer Vaccine". Discovery and Development. Rockaway, NJ, US. Associated Press. 25 July 2014.

- 1 2 "HPV Vaccine Information For Young Women". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ↑ Niccolai, LM; Hansen, CE (1 July 2015). "Practice- and Community-Based Interventions to Increase Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Coverage: A Systematic Review.". JAMA Pediatrics. 169 (7): 686–92. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0310. PMID 26010507.

- ↑ Caskey, R; Lindau, ST; Alexander, GC (November 2009). "Knowledge and early adoption of the HPV vaccine among girls and young women: results of a national survey". The Journal of Adolescent Health. 45 (5): 453–62. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.021. PMID 19837351. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ Fisher, Harriet; Trotter, Caroline L.; Audrey, Suzanne; MacDonald-Wallis, Kyle; Hickman, Matthew (2013-06-01). "Inequalities in the uptake of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Epidemiology. 42 (3): 896–908. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt049. ISSN 0300-5771. PMC 3733698

. PMID 23620381.

. PMID 23620381. - ↑ Stobbe, M (June 19, 2013). "Study: Vaccine against sexually transmitted HPV cut infections in teen girls by half". Star Tribune. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ↑ Knox, R (June 19, 2013). "Vaccine Against HPV Has Cut Infections In Teenage Girls". NPR. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Schwartz (October 2010). "HPV Vaccination's Second Act: Promotion, Competition, and Compulsion". American Journal of Public Health. 100 (10): 1841–4. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.193060. PMC 2936995

. PMID 20724671.

. PMID 20724671. - ↑ Moghtaderi, A; Adams, S (June 2016). "The Role of Physician Recommendations and Public Policy in Human Papillomavirus Vaccinations". Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 14 (3): 349–59. doi:10.1007/s40258-016-0225-6.

- 1 2 3 HPV Vaccine, NCSL.

- ↑ "HPV Vaccine: State Legislation and Statutes". www.ncsl.org. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ↑ "Immunization Information for Schools & Childcare Providers: Department of Health". www.health.ri.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ↑ "HPV Vaccine: State Legislation and Statutes". www.ncsl.org. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ↑ MIRIAM JORDAN (2008-10-01). "Gardasil Requirement for Immigrants Stirs Backlash". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ↑ "Green card seekers won't have to get HPV vaccine". 2009-11-16. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ↑ "Vaccines for Children Program (VFC)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "ACA Preventative Services Benefits for Women and Pregnant Women". Immunization for Women. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ VAP Patient Eligibility - GlaxoSmithKline

- ↑ See If You Qualify For The GSK Vaccines Access Program

- ↑ (877-822-2911)

- ↑ GSK Vaccines Access Program

- ↑ 1-800-727-5400

- ↑ GARDASIL - merck helps

- ↑ HPV Vaccine—Why Your Doctor Doesn't Offer the HPV Vaccine—Gardasil

- ↑ "Detroit News Examines Cost of HPV Vaccine Gardasil". Kaiser Family Foundation. March 29, 2007.

- ↑ A question of protection

- ↑ New York Times In Republican Race, a Heated Battle Over the HPV Vaccine

- ↑ Sprigg, Peter (2006-07-15). "Pro-Family, Pro-Vaccine—But Keep It Voluntary". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- ↑ Coyne, Brendan (2005-11-02). "Cervical Cancer Vaccine Raises 'Promiscuity' Controversy". The New Standard. Retrieved 2006-08-28.

- ↑ IF07B01, Family Research Council, February 7, 2008.

- ↑ Position Statement: Human Papillomavirus Vaccines, Focus on the Family.

- 1 2 3 4 "Opposition To HPV Vaccine Stirs Passion, Bewilderment". ripr.org. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ↑ "HPV Vaccination Does Not Lead to Increased Sexual Activity" (press release). AAP. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ "Lifesaving Politics", Ms. Magazine, pp. 12–13, Spring 2007.

- ↑ Artega, Arkaitz. "The Shape and Structure of HPV". Zimbio. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ↑ Gilkey, Melissa B.; Moss, Jennifer L.; Coyne-Beasley, Tamera; Hall, Megan E.; Shah, Parth D.; Brewer, Noel T. (2015). "Physician communication about adolescent vaccination: How is human papillomavirus vaccine different?". Preventive Medicine. 77: 181–185. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.024. PMC 4490050

. PMID 26051197.

. PMID 26051197. - ↑ Ma, B.; Roden, R.; Wu, T. C. (2010). "Current status of human papillomavirus vaccines". Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 109 (7): 481–483. doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60081-2. PMC 2917202

. PMID 20677402.

. PMID 20677402. - ↑ Jagu, S.; Karanam, B.; Gambhira, R.; Chivukula, S. V.; Chaganti, R. J.; Lowy, D. R.; Schiller, J. T.; Roden, R. B. S. (2009). "Concatenated Multitype L2 Fusion Proteins as Candidate Prophylactic Pan-Human Papillomavirus Vaccines". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 101 (11): 782–792. doi:10.1093/jnci/djp106. PMC 2689872

. PMID 19470949.

. PMID 19470949. - ↑ Tumban, E.; Peabody, J.; Tyler, M.; Peabody, D. S.; Chackerian, B. (2012). "VLPs displaying a single L2 epitope induce broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies against human papillomavirus". PLoS ONE. 7 (11): e49751. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...749751T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049751. PMC 3501453

. PMID 23185426.

. PMID 23185426. - ↑ Van Driel, W. J.; Ressing, M. E.; Brandt, R. M.; Toes, R. E.; Fleuren, G. J.; Trimbos, J. B.; Kast, W. M.; Melief, C. J. (1996). "The current status of therapeutic HPV vaccine". Annals of Medicine. 28 (6): 471–477. doi:10.3109/07853899608999110. PMID 9017105.

- ↑ Roden RB, Ling M, Wu TC (August 2004). "Vaccination to prevent and treat cervical cancer". Human Pathology. 35 (8): 971–82. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2004.04.007. PMID 15297964.