Haplogroup L2 (mtDNA)

| Haplogroup L2 | |

|---|---|

| Possible time of origin | 80,000-111,100 YBP[1] |

| Possible place of origin | West Africa or East Africa |

| Ancestor | L2─6 |

| Descendants | L2a─d, L2e |

| Defining mutations | 146, 150, 152, 2416, 8206, 9221, 10115, 13590, 16311!, 16390[2] |

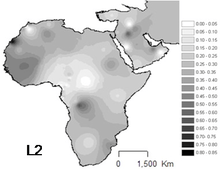

Haplogroup L2 is a human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup with a widespread modern distribution, particularly in Subequatorial Africa. Its L2a subclade is a somewhat frequent and widely distributed mtDNA cluster on the continent, as well as among African Americans.

Origin

L2 is a common lineage in Africa. It is believed to have evolved between 87,000 and 107,000 years ago[3] or approx. 90,000 YBP.[1] Its age and widespread distribution and diversity across the continent makes its exact origin point within Africa difficult to trace with any confidence.[4] Several L2 haplotypes observed in Guineans and other West Africa populations shared genetic matches with East Africa and North Africa.[5] An origin for L2b, L2c, L2d and L2e in West or Central Africa seems likely.[4] The early diversity of L2 can be observed all over the African Continent, but as we can see in Subclades section below, the highest diversity is found in West Africa. Most of subclades are largely confined to West and western-Central Africa.[6]

According to a 2015 study, "results show that lineages in Southern Africa cluster with Western/Central African lineages at a recent time scale, whereas, eastern lineages seem to be substantially more ancient. Three moments of expansion from a Central African source are associated to L2: one migration at 70–50 ka into Eastern or Southern Africa, postglacial movements 15–10 ka into Eastern Africa; and the southward Bantu Expansion in the last 5 ka. The complementary population and L0a phylogeography analyses indicate no strong evidence of mtDNA gene flow between eastern and southern populations during the later movement, suggesting low admixture between Eastern African populations and the Bantu migrants. This implies that, at least in the early stages, the Bantu expansion was mainly a demic diffusion with little incorporation of local populations".[7]

Distribution

L2 is the most common haplogroup in Africa, and it has been observed throughout the continent. It is found in approximately one third of Africans and their recent descendants.

The highest frequency occurs among the Mbuti Pygmies (64%).[8] Important presence in Western Africa, specially in Senegal (43-54%).[5] Also important in Non-Bantu populations of East Africa (44%),[9] in Sudan and Mozambique.

It is particularly abundant in Chad and the Kanembou (38% of the sample), but is also relatively frequent in Nomadic Arabs (33%) [Cerny et al. 2007] [4] and Akan people (~33%)[10]

Subclades

|

L2 has five main subgroups: L2a, L2b, L2c, L2d and L2e. The most common L2 sub group is Haplogroup L2a, both in Africa and the Levant.

Haplogroup L2 has been observed among specimens at the island cemetery in Kulubnarti, Sudan, which date from the Early Christian period (AD 550-800).[11]

Haplogroup L2a

L2a is widespread in Africa and the most common and widely distributed sub-Saharan African Haplogroup and is also somewhat frequent at 19% in the Americas among descendants of Africans (Salas et al., 2002). L2a has a possible date of origin approx. 48,000 YBP.[1]

It is particularly abundant in Chad (38% of the sample; 33% undifferentiated L2 among Chad Arabs,[12]), and in Non-Bantu populations of East Africa (Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania) at 38%.[9] About 33% in Mozambique[13] and 32% in Ghana.[10]

This subclade is characterised by mutations at 2789, 7175, 7274, 7771, 11914, 13803, 14566 and 16294. It represents 52% of the total L2 and is the only subclade of L2 to be widespread all over Africa.[14]

The wide distribution of L2a and diversity makes identifying a geographical origin difficult. The main puzzle is the almost ubiquitous Haplogroup L2a, which may have spread East and West along the Sahel Corridor in North Africa after the Last Glacial Maximum, or the origins of these expansions may lie earlier, at the beginnings of the Later Stone Age, ∼40,000 years ago.[4][14]

In East Africa L2a was found 15% in Nile Valley- Nubia, 5% of Egyptians, 14% of Cushite speakers, 15% of Semitic Amhara people, 10% of Gurage, 6% of Tigray-Tigrinya people, 13% of Ethiopians and 5% of Yemenis.[13]

Haplogroup L2a also appears in North Africa, with the highest frequency 20% Tuareg, Fulani (14%). Found also among some Algeria Arabs, it is found at 10% among Moroccan Arabs, some Moroccan Berbers and Tunisian Berbers. (watson 1997) et al., (vigilant 1991) et al. 1991.

In patients who are given the drug stavudine to treat HIV, Haplogroup L2a is associated with a lower likelihood of peripheral neuropathy as a side effect.[15]

Haplogroup L2a1

L2a can be further divided into L2a1, harboring the transition at 16309 (Salas et al. 2002).

This is observed in West Africa among the Malinke, Wolof, and others; in North Africa among the Maure/Moor, Hausa, Fulbe, and others; in Central Africa among the Bamileke, Fali, and others; in South Africa among the Khoisan family including the Khwe and Bantu speakers; and in East Africa among the Kikuyu from Kenya.

All L2 clades present in Ethiopia are mainly derived from the two subclades, L2a1 and L2b. L2a1 is defined by mutations at 12693, 15784 and 16309. Most Ethiopian L2a1 sequences share mutations at nps 16189 and 16309. However, whereas the majority (26 out of 33) African Americans share Haplogroup L2a complete sequences could be partitioned into four subclades by substitutions at nps L2a1e-3495, L2a1a-3918, L2a1f-5581, and L2a1i-15229. None of those sequences, were observed in Ethiopian 16309 L2a1 samples. (Salas 2002) et al.

Haplogroup L2a1 has also been observed among the Mahra (4.6%).[16]

Haplogroup L2a1 was found in two specimens from the Southern Levant Pre-Pottery Neolithic B site at Tell Halula, Syria, dating from the period between ca. 9600 and ca. 8000 BP or 7500-6000 BCE.[17]

Haplogroup L2a1a

Subclade L2a1a is defined by substitutions at 3918, 5285, 15244, and 15629. There are two L2a clusters that are well represented in southeastern Africans, L2a1a and L2a1b, both defined by transitions at quite stable HVS-I positions. Both of these appear to have an origin in West Africa or North West Africa (as indicated by the distribution of matching or neighboring types), and to have undergone dramatic expansion either in South East Africa or in a population ancestral to present-day Southeastern Africans.

The very recent starbursts in subclades L2a1a and L2a2 suggest a signature for the Bantu expansions, as also proposed by Pereira et al. (2001).

L2a1a is defined by a mutation at 16286. The L2a1a founder candidate dates to 2,700 (SE 1,200) years ago. (Pereira et al. 2001). However, L2a1a, as defined by a substitution at (np 16286) (Salas et al. 2002), is now supported by a coding-region marker (np 3918) (fig. 2A) and was found in four of six Yemeni L2a1 lineages. L2a1a occurs at its highest frequency in Southeastern Africa (Pereira et al. 2001; Salas et al. 2002). Both the frequent founder haplotype and derived lineages (with 16092 mutation) found among Yemenis have exact matches within Mozambique sequences (Pereira et al. 2001; Salas et al. 2002). L2a1a also occurs at a smaller frequency in North West Africa, among the Maure and Bambara of Mali and Mauritania.[18] (Rando et al. 1998; Maca-Meyer et al. 2003)

Haplogroup L2a1a1

L2a1a1 is defined by markers 6152C, 15391T, 16368C

Haplogroup L2a1b

L2a1b is defined by substitutions at 16189 and 10143. 16192 is also common in L2a1b and L2a1c; it appears in North Africa in Egypt, It also appears in Southeastern Africa and so it may also be a marker for the Bantu expansion.[4]

Haplogroup L2a1c

L2a1c often shares mutation 16189 with L2a1b, but has its own markers at 3010 and 6663. 16192 is also common in L2a1b and L2a1c; it appears in Southeastern Africa as well as East Africa.[19] This suggests some diversification of this clade in situ.

Positions T16209C C16301T C16354T on top of L2a1 define a small sub-clade, dubbed L2a1c by Kivisild et al. (2004, Figure 3) (see also Figure 6 in Salas et al. 2002), which mainly appears in East Africa (e.g. Sudan, Nubia, Ethiopia) and West Africa (e.g. Turkana, Kanuri).

In the Chad Basin, four different L2a1c types one or two mutational steps from the East and West African types were identified. (Kivisild et al.) 2004.[19] (citation on page.9 or 443)[20]

Haplogroup L2a1c1

L2a1c1 has a North African origin. It is defined by markers 198, 930, 3308, 8604, 16086. It is observed among Tunisia Sephardic, Ashkenazi, Hebrews, and Yemenis.

Haplogroup L2a1k

L2a1k is defined by markers G6722A and T12903C. It was previously described as a European-specific subclade L2a1a and detected in Czechs and Slovaks.[21]

Haplogroup L2a1l2a

L2a1l2a is recognized as an "Ashkenazi-specific" haplogroup, seen amongst Ashkenazi Jews with ancestry in Central and Eastern Europe. It has also been detected in small numbers in ostensibly non-Jewish Polish populations, where it is presumed to have come from Ashkenazi admixture.[22] However, this haplotype is only a very small proportion of Ashkenazi mitochondrial lineages; various studies (including Behar's) have put its incidence at between 1.4%-1.6%.

Haplogroup L2a2

L2a2 is characteristic of the Mbuti Pygmies.[8]

Haplogroup L2b'c

L2b'c probably evolved around 62,000 years ago.[1]

Haplogroup L2b

This subclade is predominantly found in West Africa, but it is spread all over Africa.[23]

Haplogroup L2c

L2c is most frequent in West Africa, and may have arisen there.[14] Specially present in Senegal at 39%, Cape Verde 16% and Guinea-Bissau 16%.[5]

Haplogroup L2d

L2d is most frequent in West Africa, where it may have arisen.[14] It is also found in Yemen, Mozambique and Sudan.[13]

Haplogroup L2e

L2e (former L2d2) is typical in West Africa.[4] It is also found in Tunisia,[24] and among Mandinka people from Guinea-Bissau and African Americans.[23]

Tree

This phylogenetic tree of haplogroup L2 subclades is based on the paper by Mannis van Oven and Manfred Kayser Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation[2] and subsequent published research.

- Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA)

- L1'2'3'4'5'6

- L2'3'4'6

- L2

- L2a'b'c'd

- L2a

- L2a1

- L2a1a

- L2a1a1

- L2a1a2

- L2a1a2a

- L2a1a2a1

- L2a1a2b

- L2a1a2a

- L2a1a3

- 16189 (16192)

- L2a1b

- L2a1b1

- L2a1f

- L2a1f1

- L2a1b

- 143

- L2a1c

- L2a1c1

- L2a1c2

- L2a1c3

- L2a1c4

- L2a1d

- L2a1e

- L2a1e1

- L2a1h

- 16189

- L2a1i

- L2a1j

- L2a1k

- 16192

- L2a1l

- L2a1l1

- L2a1l1a

- L2a1l2

- L2a1l1

- L2a1l

- L2a1c

- L2a1a

- L2a2

- L2a2a

- L2a2a1

- L2a2b

- L2a2b1

- L2a2a

- L2a1

- L2b'c

- L2b

- L2b1

- L2b1a

- L2b1a2

- L2b1a3

- L2b1a

- L2b1

- L2c

- L2c2

- L2c2a

- L2c3

- L2c2

- L2b

- L2d

- L2d1

- L2d1a

- L2d1

- L2a

- L2e

- L2a'b'c'd

- L2

- L2'3'4'6

- L1'2'3'4'5'6

See also

- Genealogical DNA test

- Genetic Genealogy

- Human mitochondrial genetics

- Population Genetics

- Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups

|

Phylogenetic tree of human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mitochondrial Eve (L) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L0 | L1–6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | L6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M | N | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CZ | D | E | G | Q | O | A | S | R | I | W | X | Y | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C | Z | B | F | R0 | pre-JT | P | U | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HV | JT | K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H | V | J | T | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- 1 2 3 4 Soares, Pedro; Luca Ermini; Noel Thomson; Maru Mormina; Teresa Rito; Arne Röhl; Antonio Salas; Stephen Oppenheimer; Vincent Macaulay; Martin B. Richards (4 Jun 2009). "Correcting for Purifying Selection: An Improved Human Mitochondrial Molecular Clock". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 84 (6): 82–93. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.001. PMC 2694979

. PMID 19500773. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

. PMID 19500773. Retrieved 2009-08-13. - 1 2 van Oven, Mannis; Manfred Kayser (13 Oct 2008). "Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation". Human Mutation. 30 (2): E386–E394. doi:10.1002/humu.20921. PMID 18853457. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ↑ Tishkoff et al., Whole-mtDNA Genome Sequence Analysis of Ancient African Lineages, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 24, no. 3 (2007), pp.757-68.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Salas, Antonio et al., The Making of the African mtDNA Landscape, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 71, no. 5 (2002), pp. 1082–1111.

- 1 2 3 Rosa, Alexandra; Brehm, A; Kivisild, T; Metspalu, E; Villems, R; et al. (2004). "MtDNA Profile of West Africa Guineans: Towards a Better Understanding of the Senegambia Region". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (Pt 4): 340–352. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00100.x. PMID 15225159.

- ↑ Atlas of the Human Journey: Haplogroup L2 The Genographic Project, National Geographic.

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/srep/2015/150727/srep12526/full/srep12526.html

- 1 2 Quintana-Murci et al. 2008. Maternal traces of deep common ancestry and asymmetric gene flow between Pygmy hunter–gatherers and Bantu-speaking farmers 'Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America'. 105(5): 1599

- 1 2 Sadie Anderson-Mann 2006, Phylogenetic and phylogeographic analysis of African mitochondrial DNA variation.

- 1 2 Veeramah, Krishna R et al 2010, Little genetic differentiation as assessed by uniparental markers in the presence of substantial language variation in peoples of the Cross River region of Nigeria.

- ↑ Sirak, Kendra; Frenandes, Daniel; Novak, Mario; Van Gerven, Dennis; Pinhasi, Ron (2016). Abstract Book of the IUAES Inter-Congress 2016 - A community divided? Revealing the community genome(s) of Medieval Kulubnarti using next- generation sequencing. IUAES.

- ↑ Cerezo, María; et al. (2011). "New insights into the Lake Chad Basin population structure revealed by high-throughput genotyping of mitochondrial DNA coding SNPs". PLoS One. 6 (4).

- 1 2 3 Toomas Kivisild et al., Ethiopian Mitochondria DNA Heritage: Tracking Gene Flow Across and Around the Gate of Tears, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 75, no. 5 (November 2004), pp. 752–770.

- 1 2 3 4 Antonio Torroni et al., Do the Four Clades of the mtDNA Haplogroup L2 Evolve at Different Rates?, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 69 (2001), pp. 348–1356.

- ↑ Kampira, E; Kumwenda, J; van Oosterhout, JJ; Dandara, C (Aug 2013). "Mitochondrial DNA subhaplogroups L0a2 and L2a modify susceptibility to peripheral neuropathy in malawian adults on stavudine containing highly active antiretroviral therapy". J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 63 (5): 647–52. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182968ea5. PMC 3815091

. PMID 23614993.

. PMID 23614993. - ↑ Non, Amy. "ANALYSES OF GENETIC DATA WITHIN AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FRAMEWORK TO INVESTIGATE RECENT HUMAN EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY AND COMPLEX DISEASE" (PDF). University of Florida. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Fernández, E. et al., MtDNA analysis of ancient samples from Castellón (Spain): Diachronic variation and genetic relationships, International Congress Series, vol. 1288 (April 2006), pp. 127-129.

- ↑ González, A. M. et al 2006, Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Mauritania and Mali and their Genetic Relationship to Other Western Africa Populations

- 1 2 http://www3.interscience.wiley.com

- ↑ Cˇerny, V et al 2006, A Bidirectional Corridor in the Sahel-Sudan Belt and the Distinctive Features of the Chad Basin Populations: A History Revealed by the Mitochondrial DNA Genome.

- ↑ Boris A Malyarchuk, Miroslava Derenko, Maria Perkova, Tomasz Grzybowski, Tomas Vanecek and Jan Lazur, Reconstructing the phylogeny of African mitochondrial DNA lineages in Slavs, European Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 16 (2008), pp. 1091–1096

- ↑ Marta Mielnik-Sikorska, Patrycja Daca, Boris Malyarchuk, Miroslava Derenko, Katarzyna Skonieczna, Maria Perkova, Tadeusz Dobosz, Tomasz Grzybowski, The History of Slavs Inferred from Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences PLOSOne January 14, 2013; 10.1371/journal.pone.0054360

- 1 2 Behar et al 2008b, The Dawn of Human Matrilineal Diversity Am J Hum Genet. 2008 May 9; 82(5): 1130–1140

- ↑ Costa MD et al 2009, Data from complete mtDNA sequencing of Tunisian centenarians: testing haplogroup association and the "golden mean" to longevity. ()

External links

- Ian Logan's Haplogroup L2. Mitochondrial DNA Site

- Ian Logan's L2bcd. Mitochondrial DNA Site

- Mannis van Oven's PhyloTree.org - mtDNA subtree L

- Spread of Haplogroup L2, from National Geographic