Healthcare rationing in the United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Healthcare reform in the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

|

Third-party payment models |

|

|

Healthcare rationing in the United States exists in various forms. Access to private health insurance is rationed based on price and ability to pay. Those not able to afford a health insurance policy are unable to acquire one, and sometimes insurance companies pre-screen applicants for pre-existing medical conditions and either decline to cover the applicant or apply additional price and medical coverage conditions.[1][2][3] Access to state Medicaid programs is restricted by income and asset limits via a means-test, and to other federal and state eligibility regulations. Health maintenance organizations (HMOs) that commonly cover the bulk of the population, restrict access to treatment via financial and clinical access limits.[4]

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act passed in March 2010 will prohibit insurers from limiting coverage to people with preexisting conditions beginning in 2014, which will alleviate this type of rationing.

Some in the media and academia have advocated rationing of care to limit the overall costs in the U.S. Medicare and Medicaid programs, arguing that a proper rationing mechanism is more equitable and cost-effective.[5][6][7] The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has argued that healthcare costs are the primary driver of government spending over the long-term.[8]

Background

Peter Singer wrote for the New York Times Magazine in July 2009 that healthcare is rationed in the United States:[9]

"Health care is a scarce resource, and all scarce resources are rationed in one way or another. In the United States, most health care is privately financed, and so most rationing is by price: you get what you, or your employer, can afford to insure you for. But our current system of employer-financed health insurance exists only because the federal government encouraged it by making the premiums tax deductible. That is, in effect, a more than $200 billion government subsidy for health care. In the public sector, primarily Medicare, Medicaid and hospital emergency rooms, health care is rationed by long waits, high patient copayment requirements, low payments to doctors that discourage some from serving public patients and limits on payments to hospitals."

David Leonhardt wrote in the New York Times in June 2009, that rationing presently an economic reality: "The choice isn’t between rationing and not rationing. It’s between rationing well and rationing badly. Given that the United States devotes far more of its economy to health care than other rich countries, and gets worse results by many measures, it’s hard to argue that we are now rationing very rationally." He wrote that there are three primary ways the U.S. rations healthcare:[7]

- Increases in healthcare premiums reduce worker pay. In other words, more expensive insurance premiums are reducing the growth in household income, which forces tradeoffs between healthcare services and other consumption.

- High premiums mean smaller companies cannot afford health insurance for their workers.

- Failure to provide certain types of care.

During 2007, nearly 45% of U.S. healthcare expenses were paid for by the government.[10] During 2009, an estimated 46 million individuals in the United States did not have health insurance coverage. Further, an additional 14,000 or more people lose coverage every day, due to job losses or other factors.[1]

During the 1940s, a limited supply of iron lungs for polio victims forced physicians to ration these machines. Dialysis machines for patients in kidney failure were rationed between 1962 and 1967. More recently, Tia Powell led a New York State Workgroup that set up guidelines for rationing ventilators during a flu pandemic.[11][12]

Definition

Healthcare rationing can be defined in one of two ways. Economically defined, healthcare rationing is simply limiting health care goods and services to only those who can afford to pay. In the United States this type of rationing affects about 15% of the population, who are either too poor to afford care or unwilling to buy care or simply uninsured. Defined by regulatory means, healthcare rationing involves restricting health care goods and services from even those who can afford to pay. This form of rationing would affect 85% of the American population. This second type of healthcare rationing is unfamiliar to most Americans.

Types of rationing

Rationing by Insurance companies

President Obama has noted that U.S. healthcare is rationed based on income, type of employment, and pre-existing medical conditions, with nearly 46 million uninsured. He states that millions of Americans are denied coverage or face higher premiums as a result of pre-existing medical conditions.[1]

In an e-mail to Obama supporters, David Axelrod wrote: "Reform will stop 'rationing' - not increase it.... It’s a myth that reform will mean a 'government takeover' of health care or lead to 'rationing.' To the contrary, reform will forbid many forms of rationing that are currently being used by insurance companies."[13]

A 2008 study by researchers at the Urban Institute found that health spending for uninsured non-elderly Americans is only about 43% of health spending for similar, privately insured Americans. These data imply rationing by price and ability to pay.[14]

Fareed Zakaria wrote that only 38% of small businesses provide health insurance for their employees during 2009, versus 61% in 1993, due to rising costs.[15]

An investigation by the House Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations showed that health insurers WellPoint Inc., UnitedHealth Group and Assurant Inc. canceled the coverage of more than 20,000 people, allowing the companies to avoid paying more than $300 million in medical claims over a five-year period. It also found that policyholders with breast cancer, lymphoma and more than 1,000 other conditions were targeted for rescission and that employees were praised in performance reviews for terminating the policies of customers with expensive illnesses.[16]

Private and public insurers all have their own drug formularies through which they set coverage limitations which may include referral to the insurance company for a decision as to whether the company will or will not approve its share of the costs. American formularies make generalized coverage decisions by class with cheaper drugs in classes at one end of the scale and expensive drugs with more conditions for referral and possible denial at the other.[17] Not all drugs may be in the formulary of every company and consumers are advised to check the formulary before deciding to buy insurance.[18]

The phenomena known as medical bankruptcy is unheard of in countries with universal health care in which medical copays are low. In the United States however, research shows that many bankruptcies have a strong medical component and that many of those who go bankrupt for a medical reason did have medical insurance. Medical insurance in the United States prior to the Affordable Care Act allowed annual caps or lifetime caps on coverage and, due to the high cost of care in the United States, it was not uncommon for the insured to suffer bankruptcy due to breaching these limits.

Rationing by price

A July 2009 NPR article quoted various doctors describing how America rations healthcare. Dr. Arthur Kellermann said: "In America, we strictly ration health care. We've done it for years...But in contrast to other wealthy countries, we don't ration medical care on the basis of need or anticipated benefit. In this country, we mainly ration on the ability to pay. And that is especially evident when you examine the plight of the uninsured in the United States."[19]

Rationing by price means accepting that there is no triage according to need. Thus in the private sector it is accepted that some people get expensive surgeries such as liver transplants or non life-threatening ones such as cosmetic surgery, when others fail to get cheaper and much more cost effective care such as prenatal care, which could save the lives of many fetuses and newborn children. Some places, like Oregon for example, do explicitly ration Medicaid resources using medical priorities.[20]

Polling has discovered that Americans are much more likely than Europeans or Canadians to forgo necessary health care (e.g. not seeking a prescribed medicine) on the grounds of cost.

Rationing by pharmaceutical companies

Pharmaceutical manufacturers often charge much more for drugs in the United States than they charge for the same drugs in Britain, where they know that a higher price would put the drug outside the cost-effectiveness limits applied by regulators. American patients, even if they are covered by Medicare or Medicaid, often cannot afford the copayments for drugs. That is rationing based on ability to pay.[1]

Rationing through government control

After the death of Coby Howard in 1987[21] the state of Oregon began a programme of public consultation to decide which procedures its Medicaid program should cover in an attempt to develop a transparent process for prioritizing medical services. Howard died of leukaemia which was not funded. His mother spent the last weeks of his life trying to raise $100,000 to pay for a bone marrow transplant, but the boy died before treatment could begin. John Kitzhaber began a campaign arguing that thousands of low-income Oregonians lacked access to even basic health services, much less access to transplants. A panel of experts, was appointed, the Health Services Commission, to develop a prioritized list of treatments. The state legislators decided where on the list of prioritised procedures the line of eligibility should be drawn. In 1995 there were 745 procedures, 581 of which were eligible for funding.[22]

Republican Newt Gingrich argued that the reform plans supported by President Obama expand the control of government over healthcare decisions, which he referred to as a type of healthcare rationing. He expressed concern that, although there is nothing in the proposed laws that would constitute rationing, the combination of the following three factors would increase pressure on the government to ration care explicitly for the elderly:[23] An expanded federal bureaucracy, the pending insolvency of Medicare within a decade, and the fact that 25% of Medicare costs are incurred in the final year of life.

Princeton Professor Uwe Reinhardt wrote that both public and private healthcare programs can ration, rebutting the concept that governments alone impose rationing: "Many critics of the current health reform efforts would have us believe that only governments ration things.... On the other hand, these same people believe that when, for similar reasons, a private health insurer refuses to pay for a particular procedure or has a price-tiered formulary for drugs – e.g., asking the insured to pay a 35 percent coinsurance rate on highly expensive biologic specialty drugs that effectively put that drug out of the patient’s reach — the insurer is not rationing health care. Instead, the insurer is merely allowing “consumers” (formerly “patients”) to use their discretion on how to use their own money. The insurers are said to be managing prudently and efficiently, forcing patients to trade off the benefits of health care against their other budget priorities."[24]

During 2009, former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin wrote against rationing by government entities, referring to what she interpreted as such an entity in current reform legislation as a "death panel" and "downright evil." Defenders of the plan indicated that the proposed legislation H.R. 3200 would allow Medicare for the first time to cover patient-doctor consultations about end-of-life planning, including discussions about drawing up a living will or planning hospice treatment. Patients could seek out such advice on their own, but would not be required to. The provision would limit Medicare coverage to one consultation every five years.[25] However, Palin also had supported such end of life counseling and advance directives from patients during 2008.[26]

Ezra Klein described in the Washington Post how polls indicate senior citizens are increasingly resistant to healthcare reform, due to concerns about cuts to the existing Medicare program that may be required to fund it. This is creating an unusual and potent political alliance, with Republicans arguing to protect the existing Medicare program, despite its position as one of the major entitlement programs they historically have opposed.[27] The CBO scoring of the proposed America's Affordable Health Choices Act of 2009 (also called HR3200) includes $219 billion in savings over 10 years, some of which would come from Medicare changes.[28]

Arguments for enhancing rationing processes

Peter Singer argued for enhancing the rationing processes:[1]

"Rationing health care means getting value for the billions we are spending by setting limits on which treatments should be paid for from the public purse. If we ration we won’t be writing blank checks to pharmaceutical companies for their patented drugs, nor paying for whatever procedures doctors choose to recommend. When public funds subsidize health care or provide it directly, it is crazy not to try to get value for money. The debate over health care reform in the United States should start from the premise that some form of health care rationing is both inescapable and desirable. Then we can ask, What is the best way to do it?"

Rationing based on economic value added

A concept called "quality-adjusted life year" (QALY - pronounced "qualy") is used to measure the cost-benefit of applying a particular medical procedure. It reflects the quality and quantity of life added due to incurring a particular medical expense. The measure has been used for over 30 years and is implemented in several countries to help with rationing decisions. Australia applies QALY measures for its form of Medicare to control costs and ration care, while allowing private supplemental insurance.[29]

Rationing using comparative effectiveness research

Several treatment alternatives may be available for a given medical condition, with significantly different costs yet no statistical difference in outcome. Such scenarios offer the opportunity to maintain or improve the quality of care, while significantly reducing costs, through comparative effectiveness research. Writing in the New York Times, David Leonhardt described how the cost of treating the most common form of early-stage, slow-growing prostate cancer ranges from an average of $2,400 (watchful waiting to see if the condition deteriorates) to as high as $100,000 (radiation beam therapy):[30]

Some doctors swear by one treatment, others by another. But no one really knows which is best. Rigorous research has been scant. Above all, no serious study has found that the high-technology treatments do better at keeping men healthy and alive. Most die of something else before prostate cancer becomes a problem.

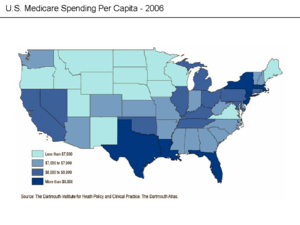

According to economist Peter A. Diamond and research cited by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the cost of healthcare per person in the U.S. also varies significantly by geography and medical center, with little or no statistical difference in outcome.[31]

Although the Mayo Clinic scores above the other two [in terms of quality of outcome], its cost per beneficiary for Medicare clients in the last six months of life ($26,330) is nearly half that at the UCLA Medical Center ($50,522) and significantly lower than the cost at Massachusetts General Hospital ($40,181)...The American taxpayer is financing these large differences in costs, but we have little evidence of what benefit we receive in exchange.

Comparative effectiveness research has shown that significant cost reductions are possible. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Director Peter Orszag stated: "Nearly thirty percent of Medicare's costs could be saved without negatively affecting health outcomes if spending in high- and medium-cost areas could be reduced to the level of low-cost areas."[32]

President Obama has provided more than $1 billion in the 2009 stimulus package to jump-start Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) and to finance a federal CER advisory council to implement that idea. Economist Martin Feldstein wrote in the Wall Street Journal that "Comparative effectiveness could become the vehicle for deciding whether each method of treatment provides enough of an improvement in health care to justify its cost."[33]

Rationing as part of fiscal discipline

Former Republican Secretary of Commerce Peter G. Peterson indicated that some form of rationing is inevitable and desirable considering the state of U.S. finances and the trillions of dollars of unfunded Medicare liabilities. He estimated that 25–33% of healthcare services are provided to those in the last months or year of life and advocated restrictions in cases where quality of life cannot be improved. He also recommended that a budget be established for government healthcare expenses, through establishing spending caps and pay-as-you-go rules that require tax increases for any incremental spending. He has indicated that a combination of tax increases and spending cuts will be required. He advocated addressing these issues under the aegis of a fiscal reform commission.[6]

Arizona recently modified its Medicaid coverage rules because of a budget problem which included denying care for expensive treatments such as organ transplants to Medicaid recipients, including those who had previously been promised funding.[34] MSNBC's Keith Olbermann and others have dubbed Governor Jan Brewer and the state legislatures as a real life death panel because many of those poor people who are now being denied funding will lose their lives or have a worsened outlook as a result of this political decision.

Old-age-based health care rationing

In America, the discussion on rationing health care for the elderly began to take root in 1983 when economist Alan Greenspan asked "whether it is worth it", referring to the use of 30% of the Medicare budget on 5 to 6 percent of those eligible who then die within a year of receiving treatment. In 1984, then Democratic governor of Colorado Richard Lamm was widely quoted (though he argues he was mis-quoted) as saying the elderly "have a duty to die and get out of the way."[35] Medical ethicist Daniel Callahan's 1987 Setting Limits: Medical Goals in an Aging Society[36] discusses whether health care should be rationed by age. In Callahan's view old people are "a new social threat" whom he considers selfish and his remedy for this threat is to use age as a criterion in limiting health care. Callahan's book has been widely discussed in the America media including the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal and in "just about every relevant professional and scholarly journal and newsletter."[37] One of the major arguments against such age-based rationing is the fact that chronological age by itself is a poor indicator of health.[38] Another major argument against Callahan's proposal is that it inverts the Western tradition by making death a possible good and life a possible evil, which means, according to Amherst College Jurisprudence professor Robert Laurence Barry, that Callahan's view amounts to "medical totalitarianism".[39] One book-length rebuttal to Callahan's views from a half dozen professors who held a conference at the University of Illinois College of Law in October 1989 can be found in 1991's Set No Limits: a Rebuttal to Daniel Callahan's Proposal to Limit Health Care edited by Robert Laurence Barry and Religious studies University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign visiting professor Gerard V. Bradley.[39]

Consequences of not controlling healthcare costs

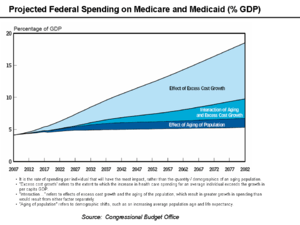

The Congressional Budget Office reported in June 2008 that:[8]

"Future growth in spending per beneficiary for Medicare and Medicaid—the federal government’s major health care programs—will be the most important determinant of long-term trends in federal spending. Changing those programs in ways that reduce the growth of costs—which will be difficult, in part because of the complexity of health policy choices—is ultimately the nation’s central long-term challenge in setting federal fiscal policy...total federal Medicare and Medicaid outlays will rise from 4 percent of GDP in 2007 to 12 percent in 2050 and 19 percent in 2082—which, as a share of the economy, is roughly equivalent to the total amount that the federal government spends today. The bulk of that projected increase in health care spending reflects higher costs per beneficiary rather than an increase in the number of beneficiaries associated with an aging population."

In other words, all other federal spending categories (e.g., Social Security, Defense, Education, and Transportation) would require borrowing to be funded, which is not feasible.

President Obama stated in May 2009: "But we know that our families, our economy, and our nation itself will not succeed in the 21st century if we continue to be held down by the weight of rapidly rising health care costs and a broken health care system...Our businesses will not be able to compete; our families will not be able to save or spend; our budgets will remain unsustainable unless we get health care costs under control."[40]

See also

- Health care reform in the United States

- Health care reform debate in the United States

- Public opinion on health care reform in the United States

- Health care in the United States

- Death panel

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 NYT-President Obama-Why We Need Healthcare Reform-August 15 2009

- ↑ Jim Jaffe, "Secret’s Out—We Already Ration Medical Care", AARP Bulletin Today, July 30, 2009

- ↑ Steven Ertelt, "Obama Health Secretary Sebelius Claims Govt. Health Care Won't Include Rationing", June 29, 2009

- ↑ Martin A. Strosberg; Joshua M. Wiener; Brookings Institution; Robert Baker (1992). Rationing America's medical care. ISBN 978-0-8157-8197-4

- ↑ NYT-Singer-Why We Must Ration Healthcare-July 15, 2009

- 1 2 Peter G. Peterson on Charlie Rose-July 3 2009-About 17 min in

- 1 2 NYT-Leonhardt-Healthcare Rationing Rhetoric Overlooks Reality-June 2009

- 1 2 CBO Testimony

- ↑ Peter Singer (July 15, 2009). "Why We Must Ration Healthcare". New York Times Magazine.

- ↑ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services-Pie Charts-2007

- ↑ Guidelines

- ↑ Cornelia Dean, Guidelines for Epidemics: Who Gets a Ventilator?, The New York Times, March 25, 2008

- ↑ Huffington Post-Nutter-Axelrod's Whitehouse E-mail-August 2009

- ↑ NYT-Reinhardt-Rationing Healthcare-What Does it Mean?

- ↑ Washington Post-Zakaria-More Crises Needed?-August 2009

- ↑ How Would You Ration Health Care? Bloomberg Businessweek citing LA Times article

- ↑ http://healthinsurance.about.com/od/prescriptiondrugs/a/understanding_formulary.htm

- ↑ http://www.ahip.org/content/default.aspx?bc=41|329|20888

- ↑ NPR-Healthcare Rationing Already Exists-July 2009

- ↑ Time Magazine-Ethics: Rationing Medical Care-Sept 09

- ↑ "A Transplant for Coby : Oregon Boy's Death Stirs Debate Over State Decision Not to Pay for High-Risk Treatments". Los Angeles Times. 28 December 1987. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Perry, Philip; Hotze, Timothy (April 2011). "Oregon's Experiment with Prioritizing Public Health Care Services". AMA Journal of Ethics. 13 (4): 241–247. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Newt Gingrich, Los Angeles Times, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 16, 2009 "Healthcare Rationing-Real Scary"

- ↑ NYT-Rheinhardt-Rationing Healthcare: What Does It Mean?-July 2009

- ↑ CBS News-Palin Weighs In On Healthcare Reform-August 2009

- ↑ Office of the Governor of Alaska-Healthcare Decisions Day

- ↑ Washington Post-Ezra Klein-No Government Healthcare!(Except for Mine)-August 2009

- ↑ CBO Report-July 14

- ↑ NYT-Singer-Why We Must Ration Healthcare-July 2009

- ↑ NYT-Leonhardt-In Health Reform, A Cancer Offers and Acid Test

- ↑ Peter Diamond-Healthcare and Behavioral Economics-May 2008

- ↑ The New Yorker-Gawande-The Cost Conundrum-June 2009

- ↑ WSJ-Feldstein-Obamacare All About Rationing-August 2009

- ↑ Lacey, Marc (December 2, 2010). "Arizona Cuts Financing for Transplant Patients". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Gov. Lamm asserts elderly, if very ill, have 'DUTY TO DIE'". NY Times. March 29, 1984.

- ↑ Setting Limits: Medical Goals in an Aging Society. Daniel Callahan. Edition reprint. Georgetown University Press, 1995 (orig. pub. 1987). ISBN 0-87840-572-0.

- ↑ Growing old in America. Beth B. Hess, Elizabeth Warren Markson. 4th Ed. Transaction Publishers, 1991. ISBN 0-88738-846-9. p.329.

- ↑ Aging: concepts and controversies. Harry R. Moody, Director of Academic Affairs, AARP. 5th Ed. Pine Forge Press, 2006. ISBN 1-4129-1520-1. p.301.

- 1 2 University of Illinois Press, 1991. ISBN 0-252-01860-5.

- ↑ President Obama-Weekly Radio Address - May 16 2009

External links

- Reforming American Healthcare from The Economist

- White House Council of Economic Advisors - The Economic Case for Healthcare Reform-Report-June 2009