Heim ins Reich

The Heim ins Reich (German pronunciation: [ˈhaɪm ɪns ˈʁaɪç]; German; "Homewards into the Empire" or "Back to the Reich"),[1] was a foreign policy pursued by Adolf Hitler beginning in 1938. The aim of Hitler's initiative was to convince all Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) who were living outside of Nazi Germany (e.g. in Austria and the western districts of Poland) that they should strive to bring these regions "home" into Greater Germany. It included areas ceded after the Treaty of Versailles, as well as other areas containing significant German populations such as the Sudetenland.

The policy was managed by VOMI (Hauptamt Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle or "Main Welfare Office for Ethnic Germans"). As a state agency of the NSDAP, it handled all Volksdeutsche issues. By 1941, the VOMI was under the control of the SS.

History

Prior to the Anschluss, a powerful transmitter in Munich bombarded Austria with propaganda of what Hitler had already done for Germany, and what he could do for his native home country Austria.[2] The annexation of Austria was presented as "enter[ing] German land as representatives of a general German will to unity, to establish brotherhood with the German people and soldiers there."[3] Similarly, the last chapter of Eugen Hadamovsky's World History on the March glorifies Hitler's obtaining Memel from Lithuania as "the latest stage in the progress of history".[4]

Concurrent with this were the beginnings of attempts to ethnically cleanse non-Germans both from Germany and from the areas intended to be part of a "Greater Germany". Alternately, Hitler also made attempts to Germanize those who were considered ethnically or racially close enough to Germans to be "worth keeping" as part of a future German nation, such as the population of Luxembourg (officially, Germany considered these populations to actually be German, but not part of the Greater German Reich, and were thus the targets of propaganda promoting this view in order to integrate them). These attempts were largely unpopular with the targets of the Germanization, and the citizens of Luxembourg voted in a 1941 referendum up to 97% against becoming citizens of Nazi Germany.[5]

Propaganda was also directed to Germans outside Nazi Germany to return as regions, or as individuals from other regions. Hitler hoped to make full use of the "German Diaspora."[6]

As part of an effort to lure ethnic Germans back to Germany,[7] folksy Heimatbriefe or "letters from the homeland" were sent to German immigrants to the United States.[8] The reaction to these was on the whole negative, particularly as they picked up.[9] Goebbels also hoped to use German-Americans to keep America neutral during the war, but this actually produced great hostility to Nazi propagandists.[10]

Newspapers in occupied Ukraine printed articles about antecedents of German rule over Ukraine, such as Catherine the Great and the Goths.[11]

Heim ins Reich in Nazi terminology and propaganda also referred to former territories of the Holy Roman Empire. Joseph Goebbels described in his diary that Belgium and the Netherlands were Heim im Reich in 1940. Belgium was supposedly lost to France by the Austrian Empire in 1794 and the Netherlands from the Holy Roman Empire in 1648 at the Peace of Westphalia. The policy for German Expansion was planned in Generalplan Ost to continue further eastwards into Poland, the Baltic states and the Soviet Union, thus creating a Greater Germany from the North Sea to the Urals.

"Heim ins Reich" in occupied Poland 1939-1944

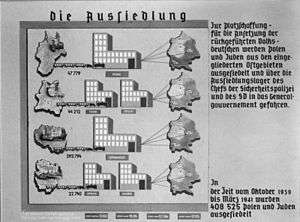

The same motto (Heim ins Reich) was also applied to a different, but somewhat related policy: the uprooting and relocation of ethnically German communities (Volksdeutsche) from some Central and Eastern European countries, which had been there for hundreds of years. The Nazi government determined which of these communities were not "viable", started propaganda among the local population, and then made arrangements and organized their transport. The use of scare tactics about the Soviet Union led to tens of thousands leaving.[12] This included Germans from Bukovina, Bessarabia, Dobruja and Yugoslavia. For example, after the Soviets had assumed control of this territory, about 45,000 ethnic Germans had left Northern Bukovina by November 1940.[13] (Stalin permitted this out of fear they would be loyal to Germany.)[14]

| Territory of origin | Year | Number of resettled Volksdeutsche |

|---|---|---|

| South Tyrol (see South Tyrol Option Agreement) | 1939–1940 | 83,000 |

| Latvia and Estonia | 1939–1941 | 69,000 |

| Lithuania | 1941 | 54,000 |

| Volhynia, Galicia, Nerewdeutschland | 1939–1940 | 128,000 |

| General Government | 1940 | 33,000 |

| North Bukovina and Bessarabia | 1940 | 137,000 |

| Romania (South Bukovina and North Dobruja) | 1940 | 77,000 |

| Yugoslavia | 1941–1942 | 36,000 |

| USSR (pre-1939 borders) | 1939–1944 | 250,000 |

| Summary | 1939–1944 | 867,000 |

In the Greater Poland (Wielkopolska) region (joined together with the Łódź district and dubbed "Wartheland" by the Germans), the Nazis' goal was the complete "Germanization", or political, cultural, social, and economic assimilation of the territory into the German Reich. In pursuit of this goal, the installed bureaucracy renamed streets and cities and seized tens of thousands of Polish enterprises, from large industrial firms to small shops, without payment to the owners. This area incorporated 350,000 such "ethnic Germans" and 1.7 million Poles deemed Germanizable, including between one and two hundred thousand children who had been taken from their parents (plus about 400,000 German settlers from the "Old Reich").[16] They were housed in farms left vacant by expulsion of the local Poles.[17] Militant party members were sent to teach them to be "true Germans".[18] Hitler Youth and League of German Girls sent young people for "Eastern Service", which entailed (particularly for the girls) assisting in Germanization efforts.[19] They were harassed by Polish partisans (Armia Krajowa) during the war. As Nazi Germany lost the war, they were expelled to remaining Germany.

Eberhardt cites estimates for the ethnic German influx provided by Szobak, Łuczak, and a collective report, ranging from 404,612 (Szobak) to 631,500 (Łuczak).[20] Anna Bramwell says 591,000 ethnic Germans moved into the annexed territories, and details the areas of colonists' origin as follows: 93,000 were from Bessarabia, 21,000 from Dobruja, 98,000 from Bukovina, 68,000 from Volhynia, 58,000 from Galicia, 130,000 from the Baltic states, 38,000 from eastern Poland, 72,000 from the Sudetenland, and 13,000 from Slovenia.[21] During "Heim ins Reich" Germans were settled in the homes of expelled Poles.

Additionally some 400,000 German officials, technical staff, and clerks were sent to those areas in order to administer them, according to "Atlas Ziem Polski" citing a joint Polish-German scholarly publication on the aspect of population changes during the war[22] Eberhardt estimates that the total influx from the Altreich was about 500,000 people.[23] Duiker and Spielvogel note that up to two million Germans had been settled in pre-war Poland by 1942.[24] Eberhardt gives a total of two million Germans present in the area of all pre-war Poland by the end of the war, 1.3 million of whom moved in during the war, adding to a pre-war population of 700,000.[23]

| Territory (region) | Number of German colonists |

|---|---|

| Warthegau | 536,951 |

| Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia | 50,204 |

| East Upper Silesia | 36,870 |

| Regierungsbezirk Zichenau | 7,460 |

| Piotr Eberhardt, Political Migrations in Poland, 1939–1948, Warsaw, 2006.[25] | |

The increase of German population was most visible in the urban centres: in Poznań, the German population increased from ~6,000 in 1939 to 93,589 in 1944; in Łódź, from ~60,000 to 140,721; and in Inowrocław, from 956 to 10,713.[26] In Warthegau, where most Germans were settled, the share of the German population increased from 6.6% in 1939 to 21.2% in 1943.[27]

See also

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Expulsion of Poles by Nazi Germany (1939-1944)

- Ethnic nationalism

- Lebensraum

- Generalplan Ost

- Volksdeutsche

- Final solution

- Holocaust

- Nazism

- Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950)

- Expulsion of Germans after World War II

- VOMI

References

- ↑ A less literal translation might be "Return to the Nation"

- ↑ Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p27 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ↑ "Marching into Austria"

- ↑ "Hadamovsky on the Memel District (1939)"

- ↑ Paul Dostert, Luxemburg unter deutscher Besatzung 1940-45. Zug der Erinnerung 2015.

- ↑ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p. 194. ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ↑ Nicholas, p. 195.

- ↑ Nicholas, p. 197.

- ↑ Nicholas, p. 199.

- ↑ Rhodes, p. 147.

- ↑ Karel C. Berkhoff, Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule p. 192. ISBN 0-674-01313-1

- ↑ Nicholas, p. 207-9.

- ↑ Leonid Ryaboshapko. Pravove stanovishche nationalinyh mensyn v Ukraini (1917-2000) - P. 259 (in Ukrainian)

- ↑ Nicholas, p. 204.

- ↑ Enzyklopadie Migration in Europa. Vom 17. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart. München: K.J.Bade, 2007, ss. 1082–1083.

- ↑ Pierre Aycoberry, The Social History of the Third Reich, 1933-1945, p 228, ISBN 1-56584-549-8

- ↑ Nicholas, p. 213-4.

- ↑ Aycoberry, p. 255.

- ↑ Nicholas, p. 215.

- ↑ Piotr Eberhardt, Political Migrations in Poland, 1939-1948, Warsaw 2006, p.24

- ↑ Anna Bramwell citing the ILO study, Refugees in the age of total war, Routledge, 1988, p.123, ISBN 0-04-445194-6

- ↑ Wysiedlenia, wypędzenia i ucieczki 1939-1959: atlas ziem Polski: Polacy, Żydzi, Niemcy, Ukraińcy. Warszawa Demart 2008

- 1 2 Eberhardt, p. 22.

- ↑ William J. Duiker, Jackson J. Spielvogel, World History, 1997: By 1942, two million ethnic Germans had been settled in Poland. page 794

- ↑ Eberhardt, p. 25.

- ↑ Eberhardt, p.26. Eberhardt refers to Polska Zachodnia..., 1961, p. 294.

- ↑ Eberhardt, p. 26.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Resettlement of Volksdeutsche. |

- R.L. Koehl RKFDV: German Resettlement and Population Policy 1939-1945 (Cambridge MA, 1957).

- Anthony Komjathy and Rebecca Stockwell German Minorities and the Third Reich: Ethnic Germans of East Central Europe between the Wars (New York and London, 1980).

- Valdis O. Lumans Himmler's Auxiliaries: The Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German National Minorities of Europe, 1933-1945 (Chapel Hill NC and London, 1993).