Henry E. Baker

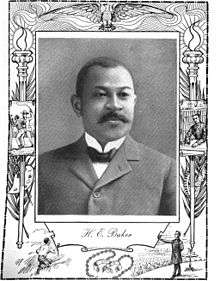

| Henry E. Baker, Jr. | |

|---|---|

Baker c. 1902 | |

| Born |

September 1, 1857 Columbia, Mississippi, United States |

| Died |

April 27, 1928 (aged 70) Washington, D.C., United States |

| Alma mater |

United States Naval Academy Ben-Hyde Benton School of Technology Howard University School of Law |

| Occupation | Patent examiner |

| Known for | Historian of African-American inventors |

| Notable work | The Colored Inventor |

Henry Edwin Baker, Jr. (September 1, 1857 – April 27, 1928) was the third African American to enter the United States Naval Academy. He later served as an assistant patent examiner in the United States Patent Office, where he would chronicle the history of African-American inventors.

Personal life and education

Baker was born on September 1, 1857, in Columbia, Mississippi, and attended the Columbus Union Academy there.[1] After attending the Naval Academy for two years he completed his education at the Ben-Hyde Benton School of Technology in Washington, D.C., graduating in 1879.[2] He graduated from Howard University School of Law in 1881 at the top of his class, and completed post-graduate work there in 1883.[2]

Naval Academy

I was several times attacked with stones, and was forced finally to appeal to the officers, when a marine was detailed to accompany me across the campus to and from mess hall at meal times. My books were mutilated, my clothes were cut, and in some instances destroyed, and all the petty annoyances which ingenuity could devise were inflicted upon me daily, and during seamanship practice attempts were often made to do me personal injury, while I would be aloft in the rigging. No one ever addressed me by name. I was called the "Moke" usually, the "damn nigger", for variety. I was shunned as if I were a veritable leper, and received curses and blows as the only method my persecutors had of relieving the monotony…

Henry E. Baker, quoted in Washington 1901

Baker was nominated by Congressman Henry W. Barry while he was living in Columbia, and was sworn in as a cadet midshipman on September 25, 1874.[3]

Like his predecessors James H. Conyers and Alonzo C. McClennan – the first and second African Americans to attend the Naval Academy, respectively – Baker also faced racist attitudes and harassment. Baker was a social outcast; his only social interaction with another midshipman – "except on occasions when he was defending himself against their assaults" – while he was at the academy occurred when a midshipman from Pennsylvania came to Baker's room at midnight and offered Baker a slice of birthday cake.[4] In order to allay Baker's suspicions the midshipman produced a letter from his mother "in which she requested that a slice be given to the colored cadet who was without friends".[4]

A fellow plebe from North Carolina, James Henry Glennon, put Baker on report for calling Glennon a "son of a bitch" on October 26, 1874.[3] The Superintendent of the Naval Academy, C.R.P. Rodgers, convened a board of inquiry under Commander William T. Sampson to investigate the incident. Glennon had not heard Baker, but other plebes testified that they had heard it and admitted that they referred to Baker as the "nigger" within his hearing.[5] The board found that Baker had said it, but that he was "incited so to act by the bearing of the other cadets".[5] Another board was convened to investigate a report of disobedience during a seamanship drill, when Baker stood still after receiving conflicting orders, but it found no misconduct.

In January 1875, Baker ran into academic trouble when he failed his semiannual exams in math and French and the Academic Board recommended dismissal. While awaiting a final ruling Baker was involved in another altercation on February 7, 1875.[6] While marching back to quarters after supper Baker was struck from behind by a snowball. Baker shouted, warning those behind him to "[t]ake care at whom you throw snow balls".[6] John Hood, a plebe from Florence, Alabama, asked Baker whom he was addressing, and when Baker replied, "You", Hood struck him in the face.[6] Another midshipman, Lawson Melton of South Carolina (who received his appointment from Robert B. Elliott, an African-American congressman) joined in the attack, but Baker managed to escape and report the incident. The following morning Hood and Melton, armed with clubs, waylaid Baker and beat him about the head before he could break free and make his escape; he also reported this incident to the officer in charge.[6] In lieu of an investigation, Hood and Melton wrote letters of explanation in which they unrepentantly justified their assault on Baker, with Melton writing:

I have been taught never to receive an insult, and now when it was offered by a Negro, I could not help striking him. I also admit, that it was ungentlemanly, thus to strike a Negro, and I deeply regret having lowered myself thus. I think Sir, that I would repeat it, on the slightest provocation."[7]

Superindendent Rogers recommended that the Secretary of the Navy, George M. Robeson, dismiss Hood and Melton for their misconduct and disregard of Baker's rights, as well as their stated intention to renew the violence; Robeson agreed.[7] (Hood was eventually reappointed by Representative Goldsmith W. Hewitt, and graduated second in the Class of 1879.) To forestall additional violence, Rogers punished the freshman with additional marching, extra drills, and restriction to quarters on Saturday evenings; these steps were effective in reducing harassment of Baker.[7]

Baker's studies improved and he passed his annual examinations in June 1875, but the Academic Board recommended that he and twenty other classmates repeat plebe year, and Robeson approved.[7] Around the same time, Baker was attacked when he said "oh Lord" to Charles Renwick Breck, a classmate from Mississippi, "in a very insulting tone".[7] Breck was dismissed, but Admiral Rogers believed that Bakers defiant attitude was partially to blame. In October 1875, Baker was involved in a quarrel with Frederick P. Meares, a plebe from North Carolina, in the mess hall during a meal.[8] Meares objected to Baker removing an empty seat between them and when it fell beneath the table classmates pushed the chair into Baker's leg. Baker blamed Meares and warned him that there would be violence if he continued. Baker was placed on report for using foul language during the altercation. A board of inquiry found that, despite his protestations to the contrary, Baker had called Meares a "God damned son of a bitch", but had been goaded into doing so.[8] Admiral Rogers recommended that Baker be dismissed and Robeson agreed.[8] Political pressure forced Robeson to reverse his decision; however, the harassment resumed after his reinstatement, and Baker resigned permanently.[9] No other blacks were appointed to the Naval Academy for the following six decades.[10]

Patent Office

Baker joined the United States Patent Office in 1877 as a copyist and rose through the ranks to Second Assistant Examiner by 1902.[2]

Writings

- Baker, Henry E. (1913). The Colored Inventor: A Record of Fifty Years. New York City: The Crisis Publishing Company.

- Baker, Henry E. (1902). "The Negro as an Inventor". In Daniel Wallace Culp (ed.). Twentieth Century Negro Literature; Or, A Cyclopedia of Thought on the Vital Topics Relating to the American Negro. Naperville, Illinois; Toronto: J.L. Nichols & Company. pp. 398–413.

- Baker, Henry E. (January 1, 1917). "The Negro in the Field of Invention". The Journal of Negro History. 2 (1): 21–36. doi:10.2307/2713474. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2713474.

See also

- Wesley A. Brown (the first African-American graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy)

- List of African-American inventors and scientists

- List of African-American writers

- List of Howard University people

- List of people from Mississippi

- List of people from Washington, D.C.

- List of United States Naval Academy alumni

References

- Notes

- ↑ Sluby, Patricia Carter (2004). The Inventive Spirit of African Americans: Patented Ingenuity. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. xxxiii. ISBN 978-0-275-96674-4. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Baker, Henry E. (1902). "The Negro as an Inventor". In Daniel Wallace Culp (ed.). Twentieth Century Negro Literature; Or, A Cyclopedia of Thought on the Vital Topics Relating to the American Negro. Naperville, Illinois; Toronto: J.L. Nichols & Company. pp. 398–413.

- 1 2 Schneller 2005, p. 35.

- 1 2 Washington, Booker T. (1901). "Democracy and Education". Documents of the Senate of the State of New York. 10. Albany: New York State Legislature. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- 1 2 Schneller 2005, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 Schneller 2005, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schneller 2005, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 Schneller 2005, p. 40.

- ↑ Gelfand, H. Michael (2006). Sea Change at Annapolis the United States Naval Academy, 1949–2000. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-8078-7747-0. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ↑ Lanning, Michael Lee (2004). The African-American Soldier from Crispus Attucks to Colin Powell (EPUB). New York City: Citadel Press/Kensington. loc. 75. ISBN 978-0-8065-3659-0. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- Bibliography

- Holmes, Keith C. (May 1, 2012). Black Inventors: Crafting over 200 Years of Success. Brooklyn, New York: Global Black Inventor Research. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-9799573-1-4. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- Schneller, Robert John (2005). Breaking the Color Barrier: The U.S. Naval Academy's First Black Midshipmen and the Struggle for Racial Equality. New York City: New York University Press. pp. 28–35. ISBN 978-0-8147-4013-2. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- Gatewood, Willard B. (1988). "Alonzo Clifton McClennan: Black Midshipman from South Carolina, 1873-1874". The South Carolina Historical Magazine. 89 (1): 24–39. JSTOR 10.2307/27568029.