Henry T. Hazard

| Henry T. Hazard | |

|---|---|

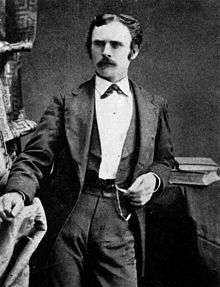

Portrait of Henry Hazard | |

| 20th Mayor of Los Angeles | |

|

In office February 25, 1889 – December 5, 1892 | |

| Preceded by | John Bryson |

| Succeeded by | William H. Bonsall (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

July 31, 1844 Evanston, Illinois |

| Died |

August 7, 1921 (aged 77) Los Angeles, California |

Henry T. Hazard (July 31, 1844 – August 7, 1921) was a California pioneer who became a land developer, a patent attorney and mayor of the city of Los Angeles. He gives his name to Hazard Park in Los Angeles.

Personal

Early

Hazard was born on July 31, 1844, in Evanston, Illinois, the son of Ariel M. Hazard. He had seven siblings. In 1853 he was brought by his parents in an oxen-drawn covered wagon at the age of about 8 on a two-year trek across the plains via Salt Lake City to a Mormon settlement in San Bernardino, California.[1][2][3]

He was about 10 when the family attempted to settle on government land a few miles west of Los Angeles; they soon left for Tulare County, where the younger children, including Henry, went to school.[1][2]

As well as working for his living, Hazard as a young man began studying law in the office of Volney E. Howard. He attended San Jose State College in 1863-64, then traveled by horseback across the plains again to the University of Michigan, where he earned his law degree.[1][2]

Marriages

Carrie Geller

Hazard was married to Carrie Geller, daughter of physician William Geller of Marysville, California, on October 3, 1873. The wedding party left Los Angeles early on a Friday morning, with the groom and his friends "in an elegant barouche, drawn by four horses." The group of carriages arrived at the Church of Our Saviour in San Gabriel, California, about 8 a.m. and the ceremony was performed by the Rev. H.H. Messenger of that city. A reception lasted until late in the evening, and the wedding party returned to Los Angeles by 2 a.m. Saturday, where the couple stayed at the Pico House.[4]

Carrie Geller Hazard died suddenly in a Los Angeles hospital on April 5, 1914. The couple had no children; her survivors were sisters Sarah E. Dougherty of San Diego, Mrs. P. Amiraux of San Francisco and Susie E. Barrow of Los Angeles and brother J.L. Geller of Los Angeles.[5]

Mildred Clough

Hazard and Mrs. Mildred Clough were married on May 5, 1919, in Prescott, Arizona, but the former mayor, age 78, later sued for an annulment on the ground of fraud, charging that she never intended to live with him, that she entered into the marriage only for the "purpose of obtaining support and maintenance and the property of Mr. Hazard" and that the marriage was never consummated.[6] Hazard bequeathed the sum of $1 to Mildred Clough in his will, and it was understood that the annulment suit was settled out of court.[7]

Homes

After their marriage in 1873, Henry and Carrie Geller Hazard lived for nineteen years in a home on South Hope Street on property later sold to a Methodist hospital, whose officials found it was "just far enough out to be quiet, just close enough in for convenience."[8] The Hazards moved in about 1892 to Third and New Hampshire, where they had built a house that was "one of the show places of the city."[5]

In 1911 Hazard was arrested along with three workmen and appeared in Police Court on a charge of removing earth from his property on West 4th Street and digging a drainage ditch without a permit.[9] In the third of three court appearances, former Mayor Hazard at first claimed the charge was politically motivated but then promised to observe the city ordinance in the future.[10]

Hazard was known for building "one of the most beautiful of the new residential show places of Los Angeles" on thirty acres south of Third Street, between Vermont Avenue and New Hampshire Avenue in the Bimini district, now part of Koreatown.[11] Planned by Eager and Eager architects, the house at 255 South New Hampshire was[2][12][13]

of a stately classic design and occupies slightly grounds of between three and four acres in extent. . . . with its formal gardens, pergolas, pool and Greek temple, [it] is today one of the most highly improved properties in Los Angeles. . . . The reception hall and corridors are in tobasco mahogany and both dining and breakfast-rooms are in Juana Costa mahogany.[12]

After America's entry into the Great War in 1917, the gardens of the Hazard estate, which included "an Italian villa and five acres of sunken gardens," were given over to vegetables instead of flowers.[2] [13] Hazard leased the property to actress Fannie Ward about 1919.[2]

Anecdotes

- Shortly after graduating from the University of Michigan, Hazard was in Los Angeles when a "battle-scarred" stagecoach was brought into the city after the driver had been killed by Indians. Hazard "mounted the coach seat, and drive back to Arizona with one passenger on the inside."[2]

- At the outset of the Chinese massacre of 1871 (Los Angeles), Hazard was in a barber's chair being shaved when a mob formed outside. "Just as he was, with his face covered with lather . . . , he mounted a barrel in the middle of the street and remonstrated with the crowd[,] attempting to stop it.[1] "He was rewarded by being shot at."[3]

- His "ability in extemporaneous speaking with well known by the public."[1]

- Hazard kept a "fine string" of racehorses and "frequently entertained friends with anecdotes of the days when he 'wrangled Missouri canaries [mules] with a twenty-foot whip.'"[1] He later disposed of his horses, bought automobiles and "drove along the highways with the same enthusiasm he [had] displayed in handling his horses."[2]

Death

Hazard was "Stricken by paralysis, in his seventy-eighth year," and died on August 7, 1921, in his "temporary home, 240 South New Hampshire street." A funeral service was conducted at Bresee Brothers, and burial followed in Evergreen Cemetery.[2][14]

Legal aftermath

Bequests

In his hand-written will, Hazard bequeathed half his estate to James Mayzle, "his trusted employee, who had been with him many years." Mayzle "became associated with Mr. Hazard at the age of 10" and was the petitioner and executor of Hazard's will. Another employee, J.L. Geller, the bookkeeper of the Hazard & Miller patent-attorney firm, received "everything appertaining to and connected with patent soliciting business, library furniture furniture, name, etc."[7]

He left a quarter of his estate to the heirs of his first wife, Carrie G. Hazard, and a quarter to his own heirs, including two sisters, Mary Taft and Abbie J. Lechler.[2][7]

Lawsuit

The Hazard estate was sued by Beulah Slater, who presented a signed agreement that Slater was to act as "companion and secretary, . . . accompany him on automobile rides and in general make life enjoyable for an old man." In the agreement, Hazard "declared his love for Mrs. Slater and also his desire to help the widow of his old friend, Guy Slater." He gave the woman a check for $25,000 which she agreed not to cash immediately. After his death, she brought suit against the estate, and a jury ruled in her favor. In 1924, however, an appeals court reversed the decision, deciding that a hundred dollars a day was too much to pay.[15][16]

Vocation

Early

After Hazard moved to Los Angeles he became a farm laborer and a drover, or mule driver, which at the time paid good money.[1]

Law and business

Returning to Los Angeles after earning his law degree in Michigan, Hazard became a criminal lawyer, and at one time received as a fee from a murder defendant a large block of land in what became the Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles.[2]

In the land boom of 1878 in Los Angeles, Hazard became a land-title and patent attorney, becoming wealthy as a result.[2] He had a partnership with Edmund A Strause, which was organized in 1907 and dissolved in August 1914.[17] He sold a partial interest in his business to Herman Miller,[2] and in 1921, he was a partner in the firm of Hazard & Miller.[6]

Public service

Hazard was one of the organizers of Los Angeles's volunteer fire department.[3] A Republican, he was Los Angeles city attorney in 1880–82, then a member of the California State Assembly in 1882–88 and mayor again in 1889–92.[1][2]

As city attorney, "he used his knowledge of land titles in compelling local railroads to give back to the city what is now known as Lincoln Park," and he was responsible for the planting of thousands of eucalyptus trees in Elysian Park.[1][2]

He favored division of the state into two parts, and he made several trips to Washington, D.C., to lobby for a free harbor at San Pedro.[1] He actively promoted the Southern Pacific Railroad's proposal to enter Los Angeles.[3]

Mayor Hazard fostered a law that insisted that the city treasurer deposit funds into banks instead of their being handled at the discretion of the treasurer.[1]

Hazard's Pavilion

Hazard and George H. Pike bought property at Fifth and Olive Streets in Los Angeles and erected an auditorium called Hazard's Pavilion. A Los Angeles Times reporter wrote in 1947 that:

Architect Charles F. Whitney caught plenty of scolding from his contemporaries for his "wild" schemes; cantilever balconies that at long last eliminated bothersome pillars, and a great bowed roof with its dome. "Many pessimists," recalled Boyle Workman, gloomily figured that those galleries were doomed to fall into space." They didn't.[18]

It was the largest auditorium in Southern California and hosted artistic, dramatic, literary, social and political activities. It was replaced by the Philharmonic Auditorium in 1905-6.[1][3]

Sketch by Toshio Aoki

Hazard was one of nine civic or social leaders who were sketched by Japanese-born artist Toshio Aoki when he visited Los Angeles from his San Francisco home in 1895. Of Hazard, Aoki said:

Make him one wise man, one man who has action among other men, much action, much spirit, much wisdom. Am I wrong? I think it is not so when I see his face; he is what you call unselfish, and the man who doe not get rich from his good work for all people He knows much law, and I make him a great man in my native costume. I do more than all. I make him a Buddhist priest—No, no, I do not make him an inner priest. He has the mustache, which he should not have at all. See, I make the Kesa, or robes of the outer priest, upon him. He is learned man and knows the law and the rules of the land.[19]

Wheel clock

In 1940 Los Angeles County forest rangers stumbled upon the rusting parts of a 60-foot-diameter "wheel clock" designed by Hazard and overgrown with brush on the side of a hill west of Castaic, California, near the Ventura County border. The axle of the clock was "set parallel to the axis of the earth and at a 90-degree angle to the slope of the mountainside." The axle was connected to the rim of the wheel by three sets of strut wires.[20] A Los Angeles Times report about the discovery went on:

The rim of the wheel was made of five layers of 1x12-inch boards. On the rim . . ., spaced at close intervals, were small hooks on which could be placed weights to balance the wheel. . . . the axle had bearings of extreme delicacy which cost $250.[20]

A neighbor who had participated in setting up the wheel said it was "so delicately balanced that it could be started rotating by the touch of a matchstick and continue to turn in the opposite direction to the rotation of the earth."[20]

References and notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Clare Wallace, Los Angeles Public Library reference file, 1938, with references as cited there

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Former Mayor Hazard Dead," Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1921, page II-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leonard Pitt and Dale Pitt, Los Angeles, A to Z, University of California Press (1997) ISBN 0-520-20274-0, pages 193-94

- ↑ "A Brilliant Wedding," Los Angeles Herald, October 4, 1873

- 1 2 "Hazard Home's Mistress Dies," Los Angeles Times, April 6, 1914, page II-5

- 1 2 "Former Mayor's Romance Empty," Los Angeles Times, February 15, 1921, page II-1

- 1 2 3 "Employee Gets Hazard Riches," Los Angeles Times, September 1, 1921, page II-1

- ↑ "About Us," Methodist Hospital of Southern California

- ↑ "Can't Get Permit; Digs in Street," Los Angeles Times, July 27, 1911, page II-2

- ↑ "He Keeps Right On A-Digging," Los Angeles Times, July 28, 1911, page II-2

- ↑ Location of the Hazard residence on Mapping L.A.

- 1 2 "Home of Pioneer Is Show Place," Los Angeles Times, December 22, 1912, page VI-1

- 1 2 "Dulcet-Toned Is Food Call," Los Angeles Times, April 30, 1917, page II-1

- ↑ "Hazard Funeral Held," Los Angeles Times, August 10, 1921

- ↑ "Appeal Is Filed on Hazard Will Fight," Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1923, page II-2

- ↑ "Companion Suit Reversed," Los Angeles Times, October 2, 1924, page 7

- ↑ "Patent Office Firm on Reef," Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1915, page II-12

- ↑ "Philharmonic Building Long Existed as a Dream," Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1947, page 2

- ↑ "To See Yourselves as Aoki Sees You," Los Angeles Herald, February 17, 1895

- 1 2 3 "Great Clock Wheel Found," Los Angeles Times, January 15, 1940, page 26

| Preceded by John Franklin Godfrey |

Los Angeles City Attorney Henry T. Hazard 1880–82 |

Succeeded by Walter D. Stephenson |