Hertwig rule

Hertwig's rule or 'long axis rule' states that a cell divides along its long axis. It was introduced by german zoologist Oscar Hertwig in 1884. The rule emphasizes the cell shape to be a default mechanism of spindle apparatus orientation. Hertwig's rule predicts cell division orientation, that is important for tissue architecture, cell fate and morphogenesis.

Discovery

In Hertwig's experiments the orientation of divisions of the frog egg was studied. Frog egg has a round shape and the first division occur in the random orientation. Hertwig compressed the egg between two parralel plates. The compression forced egg to change its shape from round to elongated. Hertwig noticed that elongated egg divides not randomly, but orthogonal to its long axis. The new daughter cells were formed along the longest axis of the cell. That observation got name of 'Hertwig's rule' or 'long axis rule'.[1]

Confirmation and Mechanism

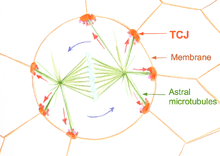

Recent studies in animal and plant systems support the 'long axis rule'. The studied systems include the mouse embryo,[2] Drosophila epithelium,[3] Xenopus blastomeres (Strauss 2006), MCDK cell monolayers [4] and plants (Gibson et al., 2011). The mechanism of the 'long axis rule' relies on interphase cell long axis sensing. However, during division many animal cell types undergo cell rounding, causing the long axis to disappear as the cell becomes round. It is at this rounding stage that the decision on the orientation of the cell division is made by the spindle apparatus. The spindle apparatus then rotates in the round cell and after several minutes the spindle position is stabilised preferentially along the interphase cell long axis. The cell then divides along the spindle apparatus orientation. The first insights into how cells could remember their long axis came from studies on the Drosophila epithelium. The study indicates Cell junction #Tricellular junctions (TCJ) participation in determining the spindle orientation. TCJ localized at the regions where three or more cells meet. As cells round up during mitosis, TCJs serve as spatial landmarks. The orientation of TCJ remains stable, independent of the shape changes associated with cell rounding. The position of TCJ encode information about interphase cell shape anisotropy to orient division in the rounded mitotic cell.[3]

Importance

Cell divisions along 'long axis' are proposed to be implicated in the morphogenesis, tissue response to stresses and tissue architecture. Division along the long cell axis reduces global tissue stress more rapidly than random divisions or divisions along the axis of mechanical stress. Long-axis division contributes to the formation of isotropic cell shapes within the monolayer.

References

- ↑ Hertwig O (1884). "Das Problem der Befruchtung und der Isotropie des Eies. Eine Theorie der Vererbung.". Jenaische Zeitschrift fur Naturwissenschaft. 18: 274.

- ↑ Gray D, Plusa B, Piotrowska K, Ha J, Glower D, Zernicka-Goetz M (2004). "First cleavage of the mouse embryo responds to change in egg shape at fertilization.". Current Biology. 14: 397–405.

- 1 2 Bosveld F, Markova O, Guirao B, Martin C, Wang Z, Pierre A, Balakireva M, Gaugue I, Ainslie A, Christophorou N, Lubensky DK, Minc N, Bellaïche Y (2016). "Epithelial tricellular junctions act as interphase cell shape sensors to orient mitosis.". Nature. 25 (530): 496–8. doi:10.1038/nature16970. PMID 26886796.

- ↑ Wyatt T, Harris A, Lam M, Cheng Q, Bellis J, Dimitracopoulos A, Kabla A, Charras G, Baumm B (2015). "Emergence of homeostatic epithelial packing and stress dissipation through divisions oriented along the long cell axis.". PNAS. 112: 5726–5731. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420585112.