Hessilhead

Hessilhead is in Beith, North Ayrshire, Scotland. Hessilhead used to be called Hazlehead or Hasslehead. The lands were part of the Lordship of Giffen, and the Barony of Hessilhead, within the Baillerie of Cunninghame and the Parish of Beith. The castle was situated at grid reference NS380532.

Hessilhead Castle

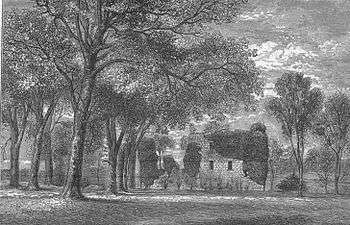

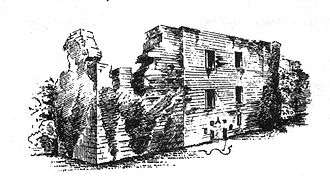

In the late 19th century, the castle was described as "now roofless and ruinous, is an oblong structure, built at two periods, measuring some 74 feet (23 m) by 38½ feet. The old west part was apparently a 15th-17th century keep; the east addition was built by Francis Montgomerie, who bought the estate in 1680. Both old and new parts are vaulted on the ground floor; the upper parts are too ruinous to describe. The mansion was allowed to become ruinous about 1776."[2] It was noted by Pont as a strong old building, surrounded with large ditches and situated on a loch.

An article in the Kilmarnock Standard of August 1949 titled Ancient Ayrshire Castles is accompanied by a photograph that shows substantial ivy-clad ruins set in a garden landscape with lawns, shrubs, trees and a well maintained paths.[3] In 1956 the Royal Commission recorded that Hessilhead Castle has been demolished. Extensive quarrying around the site has removed any possible traces of a moat. No building vestiges remain.; this is however inaccurate as traces of rubble and foundations are still visible on the site, and the drainage from the quarry does use what was once a moat.[4] Timothy Pont in around 1604 records that the castle was protected by substantial ditches and stood on a loch. This loch has long since been drained and the ditches filled in.[5]

William Roy's map of 1747 - 55[6] shows a farm town of Hazlehead and nearby, set amongst fairly extensive ornamental rides and plantations, the castle of Heeselhead (sic). Armstrong's map of 1775 marks Hazlehead[6] and finally John Thomson's map of 1832 gives the farm town of Hazelhead and the ruins of Hazlehead.[7]

Hessilhead in its later days was occupied by the family of Lord Glasgow, and after they left, the proprietor, a Mr. Macmichael, about the year 1776, took off the roof and allowed the place to go to ruin. Circa 1887 - 92 it is described as being enclosed as a garden.[2] Dobie records the despoiler of Hessilhead as a Mr. Carmichael, who sold the materials from the castle and also removed parts of the walls, as well as cutting down and selling an impressive old Yew tree.[8] In the 1960s the remains of the castle were blown up on the instructions of Howie of Dunlop.[9]

Dobie[8] also records that a little to the south of the ruined castle there was a singular echo, which slowly and plaintively repeated the voice once, throwing a melancholy charm over this scene of departed grandeur.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hessilhead Castle. |

The history of the lands of Hessilhead

The first recorded holder of the lands of Hessilhead was Hugh de Eglintoun, who obtained the lands following forfeiture. Eglin, Lord of Eglintoun[10][11] is the first of the family recorded, living during the reign of King Malcolm Canmore; he may have been one of the Saxon barons who accompanied King Malcolm (who died in 1093) on his successful return to Scotland. The family continued until Elizabeth de Eglintoun, the sole heir, married Sir John de Montgomerie of Eaglesham. Elizabeth's mother was Giles, daughter of Walter, lord high steward of Scotland, and sister of King Robert II.[12]

- The memorial to Robert Patrick of Hazlehead in Beith Auld Kirk.

- The memorial to William Ralston Patrick in Beith cemetery.

- Beith Auld kirk.

- A Hessilhead shelter belt and estate wall.

When Hugh Eglintoun of that Ilk, her father, died soon after 1378 the Montgomerie family inherited the lands and hereafter Hessilhead's history is bound up with that family.[11][13]

Sir John Montgomerie of Hessilhead and Corsecraigs inherited the estate from his father, Hugh Montgomerie of Bawgraw (Balgray). John was slain at the battle of Flodden in 1513 and the estate passed to his son Hugh, who died on 23 January 1556. Hugh's heir was his son John who was appointed one of the tutors to Hugh, third Earl of Eglintoun. John married Margaret Fraser of Knock and was succeed in 1558 by his son Hugh. This young Hugh was a member of the Convention Parliament of 1560, at which the Protestant Confession of Faith was established.

In around 1576, Gabriel Montgomerie of nearby Scotston was slain by adherents of the Montgomeries of Hessilhead. Hugh had a son Robert who inherited in 1602, passing the estate on to his son Robert circa 1623. This Robert was a Commissioner of Supply for Ayrshire and his son, also Robert, succeeded in 1648 and was one of the representatives for Ayrshire in the first parliament of King Charles II. He had a daughter, Mary, who married MacAulay of Ardincaple.

Robert Montgomerie sold Hessilhead to the seventh Earl of Eglinton's (1613–1669) second son, The Right Hon. Francis Montgomerie inherited the nearby Giffen Castle and lived an eventful life. He was one of the Lords of the Privy Council, and a Commissioner of the Treasury, in the reign of William III and Queen Anne. He was appointed in 1706 as one of the Commissioners for Scotland for the Treaty of Union.

The Act of Union was very unpopular in some quarters. A song of 1706 on the Union reads:-

|

"There's Roseberry, Glasgow, and Dupplin, |

In another, called "Lines upon the Rogues in Parliament," is the following stanza :-

|

"Thou Francis of Giffen thou's bigot as hell, |

Francis built an addition to the old tower as well as slating the roof, making it one of the finest properties in the district. Francis also planted extensively, mostly as avenues or rides running to the mansion house. This Dutch style had the avenues in straight lines and at right angles. In the 1860s much of this designed landscape still existed.[14]

In 1697 Francis was made one of the commissioners looking into witchcraft following the Christian Shaw case in which five out of 24 accused persons were burned at the stake. In 1692 the spelling of the name was Hyslehead.[15]

Francis's son John contracted such debts that Hessilhead had to be disposed of by judicial sale in 1722 and was bought by Colonel Patrick Ogilvie who had married Elizabeth, one of John's sisters. The colonel sold the property to Robert Brodie of Calderhaugh, who in turn in 1768 sold it to Michael Carmichael.[8]

The coat of arms of the Montgomeries of Hessilhead are Azure, two lances of Tournament, proper, between three Fleurs-de-lis, Or, and in the chief point an Annulet, Or, Stoned, Azure, with an Indentation in the side of the shield, on the Dexter side.[16]

The Auld Kirk of Beith had the Hessilhead loft in the East Wing. The loft and the carved wood Montgomerie of Hessilhead coat of arms were removed when the new church was built.[17]

The OS map shows that Hessilhead Cottage sat next to a well maintained walled garden, however by 1897 the garden had fallen into ruin. A gamekeepers cottage with a nearby pheasantry is marked from 1912, when a curling pond makes its first appearance, to the north-west of the castle ruins. In 1827 a lime works is shown on the map in the grounds of the castle.[18]

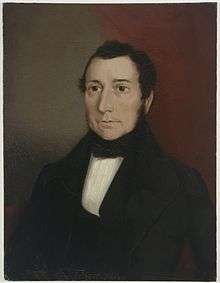

Trearne

In 1807, Dr. Robert Patrick of Trearne purchased the Hessilhead estate.[10] Robert Patrick was an army medic and was appointed Inspector of Hospitals in 1801. John Shedden Patrick F.R.S.E. was his heir in 1838 and in 1844 Robert Shedden Patrick of Trearne and Hessilhead succeeded.[19] James Dunlop lived at Trearne Lodge in 1820 with his wife. James met Major General Sir Thomas Brisbane through the Patricks of Trearne and went on to become the Astronomer Royal for New South Wales, Sir Thomas being the Governor of New South Wales and a great enthusiast for astronomy. James Dunlop died in Australia, having become a Fellow of the Royal Society, London and Edinburgh and the recipient of many medals recognising his achievements.[20]

James Dunlop.

James Dunlop.- Gateside's Patrick Memorial Hall.

- Memorial to Isobel Ralston-Patrick of Trearne who died aged 21 years.

- Memorial at Beith Cemetery to Major Robert Ralston Patrick.

Trearne House had been built about 1870, almost on the 'footprint' of an older mansion house. Mr and Mrs Ralston-Patrick lived for some time in Burnhouse Manor until their new house was ready for them. By 1877 Mr and Mrs Ralston-Patrick were living in the new Trearne. Jenny Kerr was probably the last person born at Trearne Lodge; her mother was living there with her parents when her father was a Lieutenant in the Glasgow Highlanders, and was fighting in France during the first World War.[21] Over Hessilhead was on the Trearne Estate along with Hessilhead, Townend of Hessilhead and an estate saw mill with its water wheel driven by the Dusk Water.[22] During WW2 Trearne House was used by the army, following which it became Gresham House Boarding School. The school had a cook, a matron and five or six teachers up. There would be about thirty boys in the private boarding school, many of whom had parents who worked abroad.[23]

Limestone quarries

The remains of many small and large fossiliferous limestone quarries are present in the area and have led to the destruction of much of the old estate features. Trearne House and the ancient Saint Bridget's chapel and well suffered the same fate. The flooded quarry close to the old castle is now in use by the Hessilhead Wildlife Rescue Centre for the recuperation of swans and other waterfowl. Limekilns were present in the woods below Over Hessilhead Farm and near Broadstone Hall. A 'lime works' is shown on the 1827 map of the parish.[18]

The Templelands of Cunninghame

The Knights Templar had owned considerable lands and properties in the bailiary of Cunninghame, regality of Kilwinning and in the early 17th century, Robert Montgomerie acquired the rights to these Templelands from the Sandilands family of Calder, the Lords Torphichen and thus became the feudal superior. He also had the lands of the bailiary of Kyle Stewart. The value of these lands largely lay in their near exemption from taxation. In about 1720 the lands passed to the Wallaces of Carnell, at Fiveways near Kilmarnock. Later Dr. Robert Patrick of Trearne & Hessilhead purchased the superiority, although this was of little real value after the abolition of heritable jurisdictions in 1747.[24]

Coldstream mill

Coldstream Mill was built to serve the Barony and castle of Hessilhead. It was officially known as Whitestone Mill in the Lands of Coldstream. It was first mentioned in 1782, but it may have been built circa 1783, as part of the general improvements, carried out by the Right Honourable Francis Montgomerie, who as previously stated, extended the castle so that it was for a long time reckoned to be the best house in the district.[25]

John Andrew is listed in 1782 as the heir to John Miller, his grandfather, miller in Coldstream. In 1810, the mill passed to William Fulton of Beith, by whom it was sold to David Kerr, merchant of Beith and Andrew Gibson, baker, in 1815. William Caldwell then purchased the mill and it remained with the family for the next hundred years. Thomas Caldwell was the miller in 1841, but by 1871 Thomas is farming and the miller is Robert Jack. David Fergie is the miller in 1881, Thomas having retired. By 1891 Robert Jack is the miller again and the sons of Thomas, William and Thomas, are the owners. In 1921 the Smith family bought the mill from Thomas Caldwell, Joseph Smith having been the miller since 1911. Andrew, son of Joseph, worked the mill until 1991.[25]

After being enlarged, Coldstream Mill was used for preparing animal feed or meal, grinding linseed cake, beans, maize and barley. The mill had three sets of stones, two working whilst one was being dressed (serviced and sharpened). The mill never had an electricity supply and never needed any auxiliary power thanks to the mill pond. The mill was the last traditional working water mill in Ayrshire and one of the last in Scotland.[25] Some of the items for the mill are on display at the nearby Dalgarven Mill museum near Kilwinning. The mill was converted to a private house and the waterwheel and mill pond have been preserved as part of this development.

The Farm Town of Haselet / Clachan of Hessilhead

The 1858 OS map shows a small settlement with a school, a dwelling called Damback, a sawmill and a mill dam nearby. The hamlet may have once been known at Nethertoun as well as 'Haselet' from 'Hessilhead Hamlet'.[26] The school had closed by 1897 and Howie's of Dunlop, the owners of the estate, obtained the bell in the 1930s to Dunlop. A small Hessilhead 'Farm Town' hamlet still exists (co-ordinates 55°44′34.2″N 04°34′31.9″W / 55.742833°N 4.575528°W), dating from at least the 1740s judging by William Roy's map as previously noted. The site, although undergoing rapid change, appears to be a rare survival of a typical 18th century 'Ferm Toun'. Porterfield inn his 'Rambles Round Beith' relates that the name of this clachan was 'Haselet' from 'Hasslehead Hamlet' (sic), previously 'Nethertown'.

Matthew Pollock who established Beith's Caledonia Cabinet Works in the town and at the Bark Mill was educated here and after the school's closure he obtained the bell for use at his works in Beith to signal the start and end of the day; it is now located at Netherhouses, near old Templehouse, Dunlop. The school had originally been single storied and thatched, however a second storey was added in 1844 with substantial outside steps and it was slated at this time.[27]

- An aerial view showing the mill

- The old Hessilhead school house.

- The Old Hessilhead Town Farm looking towards Tandleview.

- Old Hessilhead Town Farm looking towards Over Hessilhead and Blaelochhead.

Duskwater Cottage.

Duskwater Cottage.- Megaliths outside Duskwater Cottage.

- The old water powered water pump.

The origin of Farm Towns lies in the common medieval sub-division of land called a ploughgate (104 acres), the extent of land which one plough team of oxen could till in a year. This area was again subdivided into four husbandlands, each of 26 acres (110,000 m2). Each husbandland could provide two oxen and eight oxen were need for a plough-team. This arrangement led to small farm towns like Hessilhead being established with accommodation for at least four men in six to eight houses, taking practical considerations into account.[28] A similar 'ferm toun' existed at Bloak, near Auchentiber, until the 1890's.

Duskwater Cottage was the blacksmith's and a cobbler also worked here. A fine example of an old well survives, thirty feet deep with a sandstone slab cover, pierced with a hole that once held the hand pump.

Hessilhead Mill has been demolished, however the circular grain kiln remnants survive, attached to the ruins of the miller's house. The course of the lade is discernable and the watergate or sluice is apparent. Steps once led down to the waterwheel which was not removed but was buried in situ.

A largely intact example of a 'Victorian' era water pump survives next to the Dusk water within the clachan. This pump was powered via a small waterwheel and a sluice and weir arrangement once directed water to it. drinking water did nor usually come from water courses due to the risk of pollution by stock, etc and it is not clear what the water from the burn was used for.

Balgray

The Balgray lands were at one time a part of the Hessilhead estate, and were in the 16th century were owned by the Montgomeries. John Stevenson and John Muir were connected with these lands in the early 18th century. Only a cottage and barn survive from what was a larger group of farm buildings, recorded on OS maps, most of which survived until the mid 20th century. The 1797 (dated on the lintel) barn, category B listed, would have been thatched or slated originally, with a lime harl that has entirely disintegrated. An arched opening, now blocked up, suggests that originally this building was used as a cart shed. Ventilation slits survive on all sides.[29]

The small wing to the 1767 cottage could have been used as storage or for cattle; the surviving doocot shows that pigeons were kept in the loft above as an additional source of food. The category C(s) listed cottage, now much altered, had small windows typical of the 18th century and has some smart details that separate it from the typical rubble-built smallholding, with very prominent skewputts and cavetto eaves course illustrating its sophistication.[29]

Crookhill

Crookhill is a corruption of 'Crosshill' and makes reference in its name to the fact that as it was on the boundary of the lands held by the old Chapel of Saint Bridget then a cross was erected nearby to mark the limits of the church lands.[30] In 1672 the lands were held by John Anderson whose wife was Janet Barclay. John also held the lands of Geilsland.[31][31] Thomas had inherited by 1697 and then James Anderson. The lands of Cruckhills later passed into the ownership of Hugh Wilson[31]

The Hessilhead and Thirdpart feud

A shocking series of incidents occurred in the locality of Hessilhead, starting on 19 July 1576 when the Lady of Hessilhead slapped one Robert Kent, servant to Gabriel, brother of John Montgomerie. The servant complained to his master and Gabriel went to his brother at the old Thirdpart mansion for advice. John advised him to seek revenge and the next morning Gabriel and Robert gained entry into Hessilhead Castle where they found the lady alone, upon which they grabbed her by the hair, pulled her onto the floor, kicked her in the bowels, and bruised her shamefully. Gabriel intended to shoot the Laird, however the whole household was now awake and the two only just managed to escape by stealing a horse and locking the castle gate from the outside. The Laird,[32] Hew Montgomerie, hastened to Thirdpart where John and Gabriel came out with pistols and drawn swords and attacked Hew Montgomerie, injuring him on various parts of his body and leaving him for dead. He was rescued by some neighbours who took him to Hessilhead castle where he recovered from his wounds.

Soon afterwards, Hessilhead men, probably from Nethertoun,[26] including one named Giffen, killed Gabriel Montgomerie after setting up an ambush for him. On 26 August, John, Kent and another brother, Walter, went to try to kill the Laird, but could not find him. None of the court cases resulted in a guilty verdict, because 'honour' had been satisfied on both sides.[33][34]

The Spectral Knight of Hessilhead and the Bride of Aiket

Henry Montgomerie of Hessilhead was pledged to marry his true love, Anna Cunninghame of Aiket Castle. They were to marry upon his return from the crusades, however Allan Lockhart, son of a neighbouring Baron began to pay frequent visits to the inmates of Aiket Castle. His courtship was in vain and he would have no success unless the Crusades were to claim Henry Montgomerie. After many more months had passed Allan decided to use trickery and eventually persuaded a foot soldier recently returned from the Crusades to tell the false tale of the death of Henry Montgomerie. The ruse was carried off with success and after a short while Allan pressed his attentions again and the marriage day was set.

On the very day of the wedding, Henry returned to Hessilhead castle and discovered the treacherous act, but he fell from his horse on his way to claim his bride and died. At midnight the wedding feast was halted abruptly by the figure of the fully armour clad Neil Montgomerie striding into Aiket Castle hall, lifting up the Lady Anna and then vanishing into the night. Neither soldier nor bride were ever found.[35] The Lockhart, Loccard or Lockhard family are believed to have been the first owners of the Barony of Kilmarnock. Symington is named after a Flemish knight, Simon Loccard.

|

Alexander Montgomerie

The 16th century poet, Alexander Montgomerie was a younger son of the Renfrewshire laird Hugh Montgomerie of Hessilheid (d. 1558), and related both to the Earl of Eglinton and to King James VI (later James I of England). Nothing is known about his life before about 1580, but contemporary or near-contemporary accounts suggest that he was brought up as a Protestant, spent some time in Argyll before leaving for the Continent, and was converted to Catholicism in Spain. He may have served in the Scottish forces in The Netherlands for a time in the later 1570s.[37] He died between the years 1607 and 1611.

The range of his work is extensive, from elegant court songs to the bitter, sometimes contorted word-play of the sonnets associated with the dispute over his pension, from witty pieces addressed to the king to the profound religious sensibility of ‘A godly prayer'. Montgomerie is one of the finest of Middle Scots poets, and perhaps the greatest Scottish exponent of the sonnet form. Robert Burns was indebted to Alexander as is apparent from his imitating his style and adopting some of his quaint expressions.[38]

The Cherrie and the Slae, which he probably revised and completed shortly before his death, is an ambitious religious allegory, employing a demanding, lyrical form which suggests that it was intended for singing, despite its considerable length.[37] The Cherry and the Sloe in the title may derive from an illusion to the cherry being virtuous and the sloe being easily plucked but bitter to the taste and representing vice.[38] His poetry reaches back to the earlier Makars, Robert Henryson, William Dunbar and Gavin Douglas, and some of his work invites comparison with Baroque writers.[37] Alexander was one of the last court poets to write in Scots. A later poem was entitled a 'Spring Morning' and described one of the royal palaces, probably Linlithgow, on such a morning.[39]

Alexander's son, also Alexander, was reportedly bewitched, together with his cousin, Mrs. Vallange. The case, and therefore the witch, went to trial, because of their 'trouble and sickness', but the court's verdict isn't recorded.[40]

Archbishop Robert Montgomerie

In the 1580s the Duke of Lennox held the patronage of the Archbishopric of Glasgow and settled this 'tulchan' post on Robert Montgomerie of Hessilhead in 1581 who was however forced to resign as Archbishop of Glasgow in 1585. A 'tulchan' post was one where the patron enjoyed the emoluments of the post whilst the holder was not expected to undertake many of the duties.[41] The reformer Andrew Melville prosecuted Robert Montgomery and for this he was summoned before the Privy Council in 1584, and had to escape to England to avoid being charged with treason.

Archaeology

The Cuff Hill rocking stone (NS 3827 5542) is a large glacial erratic boulder of basaltic greenstone lying on porphyrite[4] that some associate with the Druids, part of the old Hessilhead Barony. It no longer rocks due to people digging beneath to ascertain its fulcrum.[42] It is in a small wood and surrounded by a circular drystone wall.

A cleft in the west-front of Cuff hill is still known as 'St. Inan's Chair' and said to have been used by the saint as a pulpit.[43] and a crystal clear holy well existed nearby,[5] now sadly covered over (2006). On Cuff Hill were also located a group of four standing stones, the 'Druids' Graves', rediscovered in 1813, stands nearby surrounded by an enclosing drystone dyke and also located in the area is the likely site of a pre-reformation chapel near Kirklee Green and Lochland's Loch.

A chapel and well dedicated to St. Bridget existed at nearby Trearne on a low hill, with an associated burial ground and a nook in which was set a carving of two figures, very worn and looking like a cat and a rabbit, measuring 25 inches (640 mm) by 15 inches (380 mm).[44] The ruins at Trearne were destroyed by quarrying in comparatively recent times.

Railways

Hessilhead never had a railway station; however, a number of lines ran close by, including the line from Lugton to Beith which was originally part of the Glasgow, Barrhead and Kilmarnock Joint Railway. The station opened at opened on 26 June 1873 as Beith. It was renamed Beith Town on 28 February 1953, and closed permanently to passengers on 5 November 1962. Freight services continued at the station until 1964. The station was the terminus of a five mile (8 km) branch from Lugton.[45]

The line to Beith is still in existence (as of 2008) until just before the site of Barrmill railway station, where it then heads south along the original route of the Lanarkshire and Ayrshire Railway until it reaches DM Beith. DM Beith reportedly no longer require the rail connection.

A live railway emergency exercise at Lugton on the DM Beith branchline in 2000 played a vital part in the ongoing process of protecting Scotland’s rail passengers. The exercise simulated a collision between two passenger trains carrying 270 passengers. The aim was to test the emergency services’ response and management co-ordination by replicating real accident conditions as closely as possible. Strathclyde police co-ordinated the exercise in conjunction with the rail industry in Scotland, the British Transport Police, Civil Police, Scottish Ambulance Service, Fire Brigade, local authorities and Government emergency planning co-ordinators.[46]

Hessilhead Wildlife Rescue Centre

Hessilhead is the site of a wildlife rescue centre that has been run by Andy and Gay Christie for well over 20 years. They rescue and rehabilitate injured and abandoned animals and birds. They treat over 3000 creatures a year. A swan treatment room has been purpose built and the centre owns a nearby flooded limestone quarry that is used by the rescued swans, etc. They have x-ray facilities and a surgery suite, as well as the part-time services of a veterinarian. An annual open day is held.

See also

- Eglinton Country Park The Eglintouns of Hessilhead.

- Silverwood, Ayrshire Robert Montgomerie of Silverwood and Hessilhead

- Barony of Ladyland

- Blae Loch, Beith - part of the old estate.

References

- 1 2 MacGibbon and Ross, D and T (1887-92), The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland from the Twelfth to the Eighteenth Centuries, 5 V, Edinburgh, Vol. 3, P. 376.

- 1 2 MacGibbon and Ross, D and T (1887 - 92), The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland from the Twelfth to the Eighteenth Centuries, 5 V, Edinburgh, Vol. 3, P. 375 - 7.

- ↑ Kilmarnock Standard, August 1949

- 1 2 The RCAHMS Canmoresite

- 1 2 Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. P. 194.

- 1 2 National Library of Scotland's maps

- ↑ John Thomson's map

- 1 2 3 Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. P. 204.

- ↑ Love, Dane (2005), Lost Ayrshire - Ayrshire's Lost Architectural Heritage. Pub. Birlinn Ltd. Edinburgh. ISBN 1-84158-436-3. pp 12 - 13.

- 1 2 Paterson, James (1866) History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. Vol.III - Cuninghame. Pub. James Stillie, Edinburgh. P. 490.

- 1 2 Robertson, William (1908). Ayrshire. Its History & Historic Families. Vol.2. Reprint by Grimsay Press. ISBN 1-84530-026-2 p.49.

- ↑ Douglas, Robert (1764) The Peerage of Scotland. Edinburgh. P. 228.

- ↑ Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. p. 194

- ↑ Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. P. 203.

- ↑ Hysleheade

- ↑ Paterson, James (1866), History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. Vol. III. - Cunninghame. Part I. Pub. James Stillie, Edinburgh. P. 110.

- ↑ Beith old Kirk.

- 1 2 Aitken, Robert (1827), Map of the Parish of Beith.

- ↑ Paterson, James (1866), History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. Vol. III. - Cunninghame. Part I. Pub. James Stillie, Edinburgh. P. 128 - 129.

- ↑ Service, John (1890). Thir Notandums, being the literary recreations of the Laird Canticarl of Mongrynen. Edinburgh : Y. J. Pentland. Pages 127–222

- ↑ Recollections of Jenny Kerr. Archived 18 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Recollections of John McKechnie Archived 7 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Recollections of May Henry. Archived 18 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. P. 200 - 202

- 1 2 3 Wood, J. Scott (2002), An Architectural Survey of a Meal Mill at Coldstream, by Beith, North Ayrshire. Pub. Assoc Cert Field Arch., Glasgow.

- 1 2 Porterfield, S. (1925). 'Rambles Round Beith'. Beith : Pilot Press. p. 23

- ↑ Porterfield, S. (1925). 'Rambles Round Beith'. Beith : Pilot Press. p. 24

- ↑ Dickinson, William Croft, Donaldson, G., and Milne, I. a. (1958), A Source Book of Scottish History. V. One. Pub. T. Nelson & Sons, London. p 218.

- 1 2 British Listed Buildings Retrieved : 2011-01-27

- ↑ Porterfield, S. (1925). Rambles Round Beith. Pilot Press. Page 25

- 1 2 3 Deeds of Service, Charters and Dispositions of Geilsland.

- ↑ A Guide to Local History Terminology

- ↑ Dobie, James (1876). Pont's Cunninghame topographized 1604–1608 with continuations and illustrative notices (1876). Pub. John Tweed. P. 196 - 198.

- ↑ Robertson, William (1889) The Lady of Hessilhead outraged, and Gabriel Montgomerie of Thirdpart slain. in Historical Tales and Legends of Ayrshire. Pub. Hamilton, Adams & Co. P. 273 - 287.

- ↑ Robertson, William (1889) Historical Tales and Legends of Ayrshire. Pub. Hamilton, Adams & Co. P. 340 - 357.

- ↑ MacIntosh, John (1894). Ayrshire Nights Entertainments: A Descriptive Guide to the History, Traditions, Antiquities, etc. of the County of Ayr. Pub. Kilmarnock. P. 301.

- 1 2 3 Alexander Montgomerie. A selection from his songs and poems. Ed. & Introduced by Helena M. Shire. Pub. Oliver & Boyd for The Saltire Society. (1960).

- 1 2 Macintosh, John (1894), Ayrshire Nights' Entertainments. Kilmarnock : Dunlop & Drennan. P. 369.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Agnes Mure (1948). Scottish Pageant 1513–1625. Edinburgh : Oliver & Boyd. P. 7

- ↑ Paterson, James (1866), History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. Vol. III. - Cunninghame. Part I. Pub. James Stillie, Edinburgh. P. 107.

- ↑ Porterfield, S. (1925). Rambles Round Beith'. Beith: Pilot Press. Page 22.

- ↑ Topographical Description of Ayrshire; more Particularly of Cunninghame: together with a Genealogical account of the Principal families in that Bailiwick., George Robertson, Cunninghame Press, Irvine, 1820

- ↑ Smith, John (1895). Prehistoric Man in Ayrshire. Pub. Elliot Stock. P. 83.

- ↑ Reflections on Beith and District. On the wings of time. (1994). Pub. Beith High Church Youth Group. ISBN 0-9522720-0-8. P. 21.

- ↑ Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations, Patrick Stephens Ltd, Sparkford. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.

- ↑ Live railway accident exercise. Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hessilhead. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hessilhead Castle. |

Coordinates: 55°44′42″N 4°34′57″W / 55.74500°N 4.58250°W