Indigo dye

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

2,2'-Bis(2,3-dihydro-3- oxoindolyliden), Indigotin | |

| Identifiers | |

| 482-89-3 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL599552 |

| ChemSpider | 4477009 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.898 |

| RTECS number | DU2988400 |

| UNII | 1G5BK41P4F |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C16H10N2O2 | |

| Molar mass | 262.27 g/mol |

| Appearance | dark blue crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.199 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 390 to 392 °C (734 to 738 °F; 663 to 665 K) |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| 990 µg/L (at 25 °C) | |

| Hazards | |

| EU classification (DSD) |

207-586-9 |

| R-phrases | R36/37/38 |

| S-phrases | S26-S36 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Indoxyl Tyrian purple Indican |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Indigo dye is an organic compound with a distinctive blue color (see indigo). Historically, indigo was a natural dye extracted from plants, and this process was important economically because blue dyes were once rare. A large percentage of indigo dye produced today – several thousand tons each year – is synthetic. It is the blue often associated with blue jeans.

Uses

The primary use for indigo is as a dye for cotton yarn, which is mainly for the production of denim cloth for blue jeans. On average, a pair of blue jean trousers requires 3–12 g of indigo. Small amounts are used for dyeing wool and silk.

Indigo carmine, or indigo, is an indigo derivative which is also used as a colorant. About 20 thousand tons are produced annually, again mainly for blue jeans.[1] It is also used as a food colorant, and is listed in the United States as FD&C Blue No. 2.

Natural indigoes

Plant sources

A variety of plants have provided indigo throughout history, but most natural indigo was obtained from those in the genus Indigofera, which are native to the tropics. The primary commercial indigo species in Asia was true indigo (Indigofera tinctoria, also known as I. sumatrana). A common alternative used in the relatively colder subtropical locations such as Japan's Ryukyu Islands and Taiwan is Strobilanthes cusia. Dyer's knotweed (Polygonum tinctorum) was the most important blue dye in East Asia until the arrival of the Indigofera species from the south, which yield more dye. In Central and South America, the species grown is I. suffruticosa (añil). In Europe woad containing the same dye was used for blue-dying. Several plants contain indigo, but low concentrations make them difficult to work with and the color is then more easily tainted by other dye substances, typically leading to a greenish tinge.

Natural sources also include mollusks, the Murex sea snails produce a mixture of indigo and dibromoindigo (red) which together produce a range of purple hues known as Tyrian purple. Light exposure during part of the dying process can convert the dibromoindigo into indigo resulting in blue hues known as royal blue or hyacinth purple.

Extraction

The precursor to indigo is indican, a colorless, water-soluble derivative of the amino acid tryptophan. Indican readily hydrolyzes to release β-D-glucose and indoxyl. Oxidation by exposure to air converts indoxyl to indigo. Indican was obtained from the processing of the plant's leaves, which contain as much as 0.2–0.8% of this compound. The leaves were soaked in water and fermented to convert the glycoside indican present in the plant to the blue dye indigotin.[2] The precipitate from the fermented leaf solution was mixed with a strong base such as lye, pressed into cakes, dried, and powdered. The powder was then mixed with various other substances to produce different shades of blue and purple.

History of natural indigo

Indigo was used in India, which was also the earliest major center for its production and processing.[3] The I. tinctoria species was domesticated in India.[3] Indigo, used as a dye, made its way to the Greeks and the Romans, where it was valued as a luxury product.[3]

Indigo is among the oldest dyes to be used for textile dyeing and printing. Many Asian countries, such as India, China, Japan, and Southeast Asian nations have used indigo as a dye (particularly silk dye) for centuries. The dye was also known to ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Britain, Mesoamerica, Peru, Iran, and Africa. The oldest known fabric dyed indigo dating to 6,000 years ago was discovered in 2009 at Huaca Prieta, Peru.[4]

India is believed to be the oldest center of indigo dyeing in the Old World. It was a primary supplier of indigo to Europe as early as the Greco-Roman era. The association of India with indigo is reflected in the Greek word for the dye, indikón (ινδικόν, Indian). The Romans latinized the term to indicum, which passed into Italian dialect and eventually into English as the word indigo.

In Mesopotamia, a neo-Babylonian cuneiform tablet of the seventh century BC gives a recipe for the dyeing of wool, where lapis-colored wool (uqnatu) is produced by repeated immersion and airing of the cloth. Indigo was most probably imported from India. The Romans used indigo as a pigment for painting and for medicinal and cosmetic purposes. It was a luxury item imported to the Mediterranean from India by Arab merchants.

Indigo remained a rare commodity in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. A chemically identical dye derived from the woad plant (Isatis tinctoria), was used instead. In the late 15th century, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama discovered a sea route to India. This led to the establishment of direct trade with India, the Spice Islands, China, and Japan. Importers could now avoid the heavy duties imposed by Persian, Levantine, and Greek middlemen and the lengthy and dangerous land routes which had previously been used. Consequently, the importation and use of indigo in Europe rose significantly. Much European indigo from Asia arrived through ports in Portugal, the Netherlands, and England. Spain imported the dye from its colonies in South America. Many indigo plantations were established by European powers in tropical climates; it was a major crop in Jamaica and South Carolina, with much or all of the labor performed by enslaved Africans and African Americans. Indigo plantations also thrived in the Virgin Islands. However, France and Germany outlawed imported indigo in the 16th century to protect the local woad dye industry.

Indigo was the foundation of centuries-old textile traditions throughout West Africa. From the Tuareg nomads of the Sahara to Cameroon, clothes dyed with indigo signified wealth. Women dyed the cloth in most areas, with the Yoruba of Nigeria and the Mandinka of Mali particularly well known for their expertise. Among the Hausa male dyers, working at communal dye pits was the basis of the wealth of the ancient city of Kano, and they can still be seen plying their trade today at the same pits.[5]

In Japan, indigo became especially important in the Edo period, when it was forbidden to use silk, so the Japanese began to import and plant cotton. It was difficult to dye the cotton fiber except with indigo. Even today indigo is very much appreciated as a color for the summer Kimono Yukata, as this traditional clothing recalls Nature and the blue sea.

Newton used "indigo" to describe one of the two new primary colors he added to the five he had originally named, in his revised account of the rainbow in Lectiones Opticae of 1675.[6]

In North America indigo was introduced into colonial South Carolina by Eliza Lucas Pinckney, where it became the colony's second-most important cash crop (after rice).[7] As a major export crop, indigo supported plantation slavery there.[8] When Benjamin Franklin sailed to France in November 1776 to enlist France's support for the American Revolutionary War, 35 barrels of indigo were on board the Reprisal, the sale of which would help fund the war effort.[9] In colonial North America, three commercially important species are found: the native I. caroliniana, and the introduced I. tinctoria and I. suffruticosa.[10]

Because of its high value as a trading commodity, indigo was often referred to as blue gold.[11]

Peasants in Bengal revolted against unfair treatment by the East India Company traders/planters in what became known as the Indigo revolt in 1859, during the British Raj of India. The play Nil Darpan by Dinabandhu Mitra is based on the slavery and forced cultivation of indigo.

The demand for indigo in the 19th century is indicated by the fact that in 1897, 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi) were dedicated to the cultivation of indican-producing plants, mainly in India. By comparison, the country of Luxembourg is 2,586 km2 (998 sq mi).[1]

Era of synthetic indigo

In 1897, 19,000 tons of indigo were produced from plant sources. Largely due to advances in organic chemistry, production by natural sources dropped to 1,000 tons by 1914 and continued to contract. These advances can be traced to 1865 when the German chemist Adolf von Baeyer began working on the synthesis of indigo. He described his first synthesis of indigo in 1878 (from isatin) and a second synthesis in 1880 (from 2-nitrobenzaldehyde). (It was not until 1883 that Baeyer finally determined the structure of indigo.[12]) The synthesis of indigo remained impractical, so the search for alternative starting materials at BASF and Hoechst continued. Johannes Pfleger[13] and Karl Heumann eventually came up with industrial mass production synthesis.[14] The synthesis of N-(2-carboxyphenyl)glycine from the easy to obtain aniline provided a new and economically attractive route. BASF developed a commercially feasible manufacturing process that was in use by 1897. In 2002, 17,000 tons of synthetic indigo were produced worldwide.

Developments in dyeing technology

Indigo white

Indigo is a challenging dye because it is not soluble in water. To be dissolved, it must undergo a chemical change (reduction). Reduction converts indigo into "white indigo" (leuco-indigo). When a submerged fabric is removed from the dyebath, the white indigo quickly combines with oxygen in the air and reverts to the insoluble, intensely colored indigo. When it first became widely available in Europe in the 16th century, European dyers and printers struggled with indigo because of this distinctive property. It also required several chemical manipulations, some involving toxic materials, and had many opportunities to injure workers. In the 19th century, English poet William Wordsworth referred to the plight of indigo dye workers of his hometown of Cockermouth in his autobiographical poem "The Prelude". Speaking of their dire working conditions and the empathy that he feels for them, he wrote,

A preindustrial process for production of indigo white, used in Europe, was to dissolve the indigo in stale urine. A more convenient reductive agent is zinc. Another preindustrial method, used in Japan, was to dissolve the indigo in a heated vat in which a culture of thermophilic, anaerobic bacteria was maintained. Some species of such bacteria generate hydrogen as a metabolic product, which convert insoluble indigo into soluble indigo white. shibori (tie-dye), kasuri, katazome, and tsutsugaki. Examples of clothing and banners dyed with these techniques can be seen in the works of Hokusai and other artists.

Direct printing

Two different methods for the direct application of indigo were developed in England in the 18th century and remained in use well into the 19th century. The first method, known as 'pencil blue' because it was most often applied by pencil or brush, could be used to achieve dark hues. Arsenic trisulfide and a thickener were added to the indigo vat. The arsenic compound delayed the oxidation of the indigo long enough to paint the dye onto fabrics.

The second method was known as 'China blue' due to its resemblance to Chinese blue-and-white porcelain. Instead of using an indigo solution directly, the process involved printing the insoluble form of indigo onto the fabric. The indigo was then reduced in a sequence of baths of iron(II) sulfate, with air-oxidation between each immersion. The China blue process could make sharp designs, but it could not produce the dark hues possible with the pencil blue method.

Around 1880, the 'glucose process' was developed. It finally enabled the direct printing of indigo onto fabric and could produce inexpensive dark indigo prints unattainable with the China blue method.

Since 2004, freeze-dried indigo, or instant indigo, has become available. In this method, the indigo has already been reduced, and then freeze-dried into a crystal. The crystals are added to warm water to create the dye pot. As in a standard indigo dye pot, care has to be taken to avoid mixing in oxygen. Freeze-dried indigo is simple to use, and the crystals can be stored indefinitely as long as they are not exposed to moisture.[15]

Chemical properties

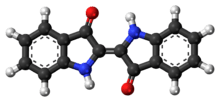

Indigo is a dark blue crystalline powder that sublimes at 390–392 °C (734–738 °F). It is insoluble in water, alcohol, or ether, but soluble in DMSO, chloroform, nitrobenzene, and concentrated sulfuric acid. The chemical formula of indigo is C16H10N2O2.

The molecule absorbs light in the orange part of the spectrum (λmax = 613 nm).[16] The compound owes its deep color to the conjugation of the double bonds, i.e. the double bonds within the molecule are adjacent and the molecule is planar. In indigo white, the conjugation is interrupted because the molecule is nonplanar.

Chemical synthesis

Given its economic importance, indigo has been prepared by many methods. The Baeyer-Drewson indigo synthesis dates back to 1882. It involves an aldol condensation of o-nitrobenzaldehyde with acetone, followed by cyclization and oxidative dimerization to indigo. This route is highly useful for obtaining indigo and many of its derivatives on the laboratory scale, but was impractical for industrial-scale synthesis. Johannes Pfleger[13] and Karl Heumann (de) eventually came up with industrial mass production synthesis.[14] The first commercially practical route is credited to Pfleger in 1901. In this process, N-phenylglycine is treated with a molten mixture of sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, and sodamide. This highly sensitive melt produces indoxyl, which is subsequently oxidized in air to form indigo. Variations of this method are still in use today. An alternative and also viable route to indigo is credited to Heumann in 1897. It involves heating N-(2-carboxyphenyl)glycine to 200 °C (392 °F) in an inert atmosphere with sodium hydroxide. The process is easier than the Pfleger method, but the precursors are more expensive. Indoxyl-2-carboxylic acid is generated. This material readily decarboxylates to give indoxyl, which oxidizes in air to form indigo.[1] The preparation of indigo dye is practiced in college laboratory classes according to the original Baeyer-Drewsen route.[17]

Indigo derivatives

The benzene rings in indigo can be modified to give a variety of related dyestuffs. Thioindigo, where the two NH groups are replaced by S atoms, is deep red. Tyrian purple is a dull purple dye that is secreted by a common Mediterranean snail. It was highly prized in antiquity. In 1909, its structure was shown to be 6,6'-dibromoindigo. It has never been produced on a commercial basis. The related Ciba blue (5,7,5′,7′-tetrabromoindigo) is, however, of commercial value. Indigo and its derivatives featuring intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonding have very low solubility in organic solvents. They can be made soluble using transient protecting groups such as the tBOC group, which suppresses intermolecular bonding.[18] Heating of the tBOC indigo results in efficient thermal deprotection and regeneration of the parent H-bonded pigment.

Treatment with sulfuric acid converts indigo into a blue-green derivative called indigo carmine (sulfonated indigo). It became available in the mid-18th century. It is used as a colorant for food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics.

Indigo as an organic semiconductor

Indigo and some of its derivatives are known to be ambipolar organic semiconductors when deposited as thin films by vacuum evaporation.[19]

Safety and the environment

Indigo has a low oral toxicity, with an LD50 of 5000 mg/kg in mammals.[1] In 2009, large spills of blue dyes had been reported downstream of a blue jeans manufacturer in Lesotho.[20]

See also

- Nilbidraha (Indigo Revolt)

References

- 1 2 3 4 Elmar Steingruber "Indigo and Indigo Colorants" Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2004, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi: 10.1002/14356007.a14_149.pub2

- ↑ Schorlemmer, Carl (1874). A Manual of the Chemistry of the Carbon compounds; or, Organic Chemistry. London. Quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989

- 1 2 3 Kriger & Connah, page 120

- ↑ Splitstoser JC, Dillehay TD, Wouters J, Claro A (2016-09-14). "Early pre-Hispanic use of indigo blue in Peru". Science Advances. 2 (9). doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501623. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ Kriger, Colleen E. & Connah, Graham (2006). Cloth in West African History. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 0-7591-0422-0.

- ↑ Quoted in Hentschel, Klaus (2002). Mapping the spectrum: techniques of visual representation in research and teaching. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-19-850953-0.

- ↑ Eliza Layne Martin. "Eliza Lucas Pinckney:Indigo in the Atlantic World" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-08-24.

- ↑ Andrea Feeser, Red, White, and Black Make Blue: Indigo in the Fabric of Colonial South Carolina Life (University of Georgia Press; 2013)

- ↑ Schoenbrun, David (1976). Triumph in Paris: The Exploits of Benjamin Franklin. New York: Harper & Row. p. 51. ISBN 0-06-013854-8.

- ↑ David H. Rembert, Jr. (1979). "The indigo of commerce in colonial North America". Economic Botany. 33 (2): 128–134. doi:10.1007/BF02858281.

- ↑ "History of Indigo & Indigo Dyeing". wildcolours.co.uk. Wild Colours and natural Dyes. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

Indigo was often referred to as Blue Gold as it was an ideal trading commodity; high value, compact and long lasting

- ↑ Adolf Baeyer (1883) "Ueber die Verbindungen der Indigogruppe" [On the compounds of the indigo group], Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin, 16 : 2188-2204 ; see especially p. 2204.

- 1 2 http://history.evonik.com/sites/geschichte/en/personalities/pfleger-johannes/pages/default.aspx

- 1 2 http://www.ingenious.org.uk/site.asp?s=RM&Param=1&SubParam=1&Content=1&ArticleID=%7BCBDF1082-9F5C-498F-A769-B33A7DA83B30%7D&ArticleID2=%7B3C4444FC-FC4D-4498-B0B4-8B8A47C5BA76%7D&MenuLinkID=%7BA54FA022-17E2-483C-B937-DEC8B8964C33%7D

- ↑ Judith McKenzie McCuin. "Directions for Instant Indigo". Archived from the original on 2004-11-16. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ↑ Wouten, J.; Verhecken, A. (1991). "High-performance liquid chromatography of blue and purple indigoid natural dyes". Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists. 107: 266–269.

- ↑ McKee, James R.; Zanger, Murray (1991). "A microscale synthesis of indigo: Vat dyeing". Journal of Chemical Education. 68: A242. doi:10.1021/ed068pA242.

- ↑ Głowacki, Eric Daniel; Voss, Gundula; Demirak, Kadir; Havlicek, Marek; Sünger, Nevsal; et al. (2013). "A facile protection–deprotection route for obtaining indigo pigments as thin films and their applications in organic bulk heterojunctions". Chemical Communications (54): 6063–6065. doi:10.1039/C3CC42889C.

- ↑ Irimia-Vladu, Mihai; Głowacki, Eric D.; Troshin, Pavel A.; Schwabegger, Günther; Leonat, Lucia; Susarova, Diana K.; Krystal, Olga; Ullah, Mujeeb; Kanbur, Yasin; Bodea, Marius A.; Razumov, Vladimir F.; Sitter, Helmut; Bauer, Siegfried; Sarıçiftçi, Niyazi Serdar (2012). "Indigo - A Natural Pigment for High Performance Ambipolar Organic Field Effect Transistors and Circuits". Advanced Materials. 24 (3): 375. doi:10.1002/adma.201102619.

- ↑ "Gap alarm". The Sunday Times. 2009-08-09. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

Further reading

- Balfour-Paul, Jenny (2016). Indigo: Egyptian Mummies to Blue Jeans. London: British Museum Press. pp. 264 pages. ISBN 0-7141-1776-5.

- Ferreira, E.S.B.; Hulme A. N.; McNab H.; Quye A. (2004). "The natural constituents of historical textile dyes". Chemical Society reviews. 33 (6): 329–36. doi:10.1039/b305697j. PMID 15280965.

- Sequin-Frey, Margareta (1981). "The chemistry of plant and animal dyes" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 58 (4): 301. Bibcode:1981JChEd..58..301S. doi:10.1021/ed058p301.

External links

- Plant Cultures: botany, history and uses of indigo

- Pubchem page for indigotine

- FD&C regulation on indigotine

- Textile Dyeing on DMOZ