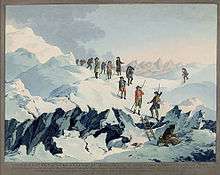

High mountain tour

A high mountain tour (German: Hochtour) is a mountain tour that takes place in the zone that is covered by ice all year round, the nival zone. High mountain tours require special preparation and equipment.

Alpine Hochtour

In the Alps a high mountain tour is known in the German-speaking areas as a Hochtour where, above a height of about 3,000 metres, many mountains are at least partly glaciated. Important historic milestones in the development of high mountain touring in the Alps were the first ascents of the Ankogel (3,262 m) in 1762, Mont Blanc (4,810 m) in 1786, the Großglockner (3,798 m) in 1800 and the Ortler (3,905 m) in 1804 as well as the conquest of many high western Alpine summits during the golden age of Alpinism around the middle of the 19th century.[1] In other parts of the world the term may be misleading. For example, in many non-Alpine areas, such as the polar regions, much lower mountains are glaciated. On the other hand, the summits of much higher peaks in the tropics are not always in the nival zone. As a result, their ascent cannot automatically be described as a high mountain tour using the Alpine definition, even if they share some of the features of Alpinism, such as requiring a certain acclimatization. Mountaineering expeditions in which elevation plays a particularly important role, especially those from about 7,000 m are no longer referred to as high mountain tours, but tend to be described by the term high altitude mountaineering.[2]

Special requirements

In glaciated terrain the risk of crevasses means that even technically easy walks require the use of rope, crampons and ice axes as well as knowledge of safety and rescue techniques. Techniques and equipment, the use of which can become especially important in high mountain tours, include crevasse rescue, the T anchor, the ice screw and snow protection. Walking with a rope requires a roped team to be formed and makes trekking alone dangerous. In addition, a certain level of fitness and height acclimatization is often unavoidable. Especially for mountain tours in high mountains such as the Himalayas, the Karakorum or the Andes, which reach elevations of over 6,000 metres above sea level, one or two weeks should be allowed dor acclimatization.[3] Low temperatures may also be an important factor.

By contrast, classic high mountain tours require not just sure-footedness and a head for heights but the ability to handle greater technical difficulty in rock and ice climbing as well as mixed climbing in combined rock and ice terrain.[3]

The dangers and problems presented by high mountain touring, as in sports climbing, are caused less by actual the actual technical difficulty of climbing than by the (often rapidly changing) external conditions. The description of the requirements of a tour with the aid of climbing grade scales is therefore problematic. As a result, such scales attempt to take into account to a greater extent as the severity of a route or its fitness requirements. An example of an established rating system for Alpinism is the SAC Mountain and High Mountain Tour Scale.[4]

Map reading and the ability to read the weather may also be important in high mountain touring. When snow falls a knowledge of avalanche behaviour is necessary, even in the summer months. High Alpine terrain is currently subject to a particularly high degree of change in terms of glacier retreat and climate change, which can both increase or decrease the difficulty and dangers of high mountain touring.[5]

References

- ↑ Stefan Winter (2003) (in German), Richtig Hochtouren, München: BLV, pp. 10-11, ISBN 3-405-16444-3

- ↑ Stefan Winter (2003) (in German), Richtig Hochtouren, München: BLV, pp. 161, ISBN 3-405-16444-3

- 1 2 Stefan Winter (2003) (in German), Richtig Hochtouren, München: BLV, pp. 12-16, ISBN 3-405-16444-3

- ↑ Ueli Mosemann (2005), "anspruchsvoll, exponiert und heikel : Bewertungssysteme für klassische Bergsportarten" (in German), bergundsteigen (Innsbruck) (2): pp. 30-34, http://www.bergundsteigen.at/file.php/archiv/2005/2/print/30-34%20%28bewertungssysteme%20fuer%20klassische%20bergsportarten%29.pdf. Retrieved 2010-11-30

- ↑ Dario-Andri Schwörer (2002), "Klimaänderung und Alpinismus" (in German), bergundsteigen (Innsbruck) (3): pp. 18-21, http://www.bergundsteigen.at/file.php/archiv/2002/3/18-21%20%28klimaaenderung%20und%20alpinismus%29.pdf. Retrieved 2010-11-30

Literature

- Stefan Winter (2003) (in German), Richtig Hochtouren, Munich: BLV, ISBN 3-405-16444-3