Hill & Adamson

|

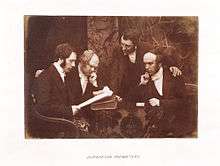

Composite photograph of Hill (left) and Adamson, both circa 1845 | |

| Formation | 1843 |

|---|---|

| Extinction | 1848 |

| Purpose | photography studio, producing salt prints from calotype negatives |

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 55°57′16″N 3°11′07″W / 55.954361°N 3.185335°W |

Key people |

David Octavius Hill Robert Adamson |

| Affiliations | David Brewster |

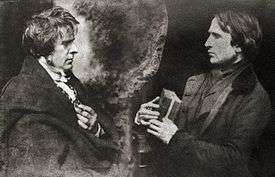

In 1843 painter David Octavius Hill joined engineer Robert Adamson to form Scotland's first photographic studio.[1] During their brief partnership that ended with Adamson's untimely death, Hill & Adamson produced "the first substantial body of self-consciously artistic work using the newly invented medium of photography."[2] Watercolorist John Harden, on first seeing Hill & Adamson's calotypes in November 1843, wrote, "The pictures produced are as Rembrandt's but improved, so like his style & the oldest & finest masters that doubtless a great progress in Portrait painting & effect must be the consequence."[3]

Free Church of Scotland

Hill was present at the Disruption Assembly in 1843 when over 450 ministers walked out of the Church of Scotland assembly and down to another assembly hall to found the Free Church of Scotland. He decided to record the dramatic scene with the encouragement of his friend Lord Cockburn and another spectator, the physicist Sir David Brewster who suggested using the new invention, photography, to get likenesses of all the ministers present. Brewster was himself experimenting with this technology which only dated back to 1839, and he introduced Hill to another enthusiast, Robert Adamson. Hill & Adamson took a series of photographs of those who had been present and of the setting. The 5-foot x 11-foot 4 inches (1.53m x 3.45m) painting was eventually completed in 1866.[4]

Photography studio

Their collaboration, with Hill providing skill in composition and lighting, and Adamson considerable sensitivity and dexterity in handling the camera, proved extremely successful, and they soon broadened their subject matter. Adamson's studio, "Rock House", on the Calton Hill in Edinburgh became the centre of their photographic experiments. Using the calotype process, they produced a wide range of portraits depicting well-known Scottish luminaries of the time, including Hugh Miller, both in the studio and in outdoors settings, often amongst the elaborate tombs in Greyfriars Kirkyard.[4]

They photographed local and Fife landscapes and urban scenes, including images of the Scott Monument under construction in Edinburgh. As well as the great and the good, they photographed ordinary working folk, particularly the fishermen of Newhaven, and the fishwives who carried the fish in creels the 3 miles (5 km) uphill to the city of Edinburgh to sell them round the doors, with their cry of "Caller herrin" (fresh herring). They produced several groundbreaking "action" photographs of soldiers and – perhaps their most famous photograph – two priests walking side by side.[4]

Their partnership produced around 3,000 different photographs, but was cut short after only four years due to the ill health and untimely death of Adamson in 1848. Hill became less active and abandoned the studio after several months, but continued to sell prints of the photographs and use them as an aid for composing paintings.[4]

They had an assistant, Jessie Mann, who worked with them for at least three years until Adamson's death.[5][6][7][8][9] It is reasoned that Mann is the assistant that made the photograph of the King of Saxony in 1844, taken at the studio whilst Hill and Adamson were unavailable.[5][8] A resulting print is now in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.[5][8]

Historical re-evaluation

A web page of the University of Glasgow Library notes, "Early scholarship by art historians usually credited Hill as the sole author of the photographic prints. Some later historians had disparagingly added "with Adamson" as a credit. Scholars today recognise that the partnership was crucial to the production of their amazing photographic works. Adamson's solo work was technically proficient but lacked flair and spontaneity before he met Hill. Equally, Hill's photographic efforts after the death of Adamson were dismal. It is clear that both men played a crucial role in the creation and the execution of the final images."[10]

Gallery

| Selected artwork by Hill & Adamson | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Notes

- ↑ Union List of Artist Names

- ↑ Daniel, Malcolm (2004). Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

- ↑ As cited in Daniel, Malcom (2004). Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

- 1 2 3 4 Michaelson, Katherine (1970). Scottish Arts Council

- ↑ Crompton, Sarah (6 May 2015). "She takes a good picture: six forgotten female pioneers of photography". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ↑ Roddy Simpson (2012). The Photography of Victorian Scotland. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9780748654642.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Phil (13 April 2011). "Scottish woman who was a camera pioneer". Glasgow: The Herald (Glasgow). Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ↑ Miller, Phil (16 April 2016). "Is this the mysterious Scottish woman who helped pioneer photography?". Glasgow: The Herald (Glasgow). Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ↑ University of Glasgow Library, Hill & Adamson Biographies

References

- "Union List of Artist Names". J. Paul Getty Trust. 2004. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Daniel, Malcolm (October 2004). "David Octavius Hill (1802–1870) and Robert Adamson (1821–1848) (1840s)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 28 February 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Michaelson, Katherine (1970). David Octavius Hill 1802–1870 & Robert Adamson 1821–1848. Edinburgh: Scottish Arts Council.

- "Hill & Adamson Biographies". University of Glasgow Library. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hill & Adamson. |

- Hill & Adamson Collection at Art Institute of Chicago

- Hill & Adamson Collection at Capital Collections

- Hill & Adamson Collection at George Eastman House

- Hill & Adamson Collection at Glasgow School of Art Flickr photostream

- Hill & Adamson Collection at Google Art Project

- Hill & Adamson Collection at J. Paul Getty Museum

- Hill & Adamson Collection at Library of Congress

- Hill & Adamson Collection at National Gallery of Art

- Hill & Adamson Collection at National Gallery of Canada

- Hill & Adamson Collection at National Gallery of Scotland

- Hill & Adamson Collection at National Portrait Gallery, London

- Hill & Adamson Collection at Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Hill & Adamson Collection at Preus Museum Flickr photostream

- Hill & Adamson Collection at Rijksmuseum

- Hill & Adamson Collection at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- Hill & Adamson Collection at University of Edinburgh

- Hill & Adamson Collection at Victoria & Albert Museum

_the_line'%3B_Newhaven_fisherman_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg)