History of turnpikes and canals in the United States

The history of turnpikes and canals in the United States dates to work accomplished and attempted in the original thirteen colonies, predicated on European technology and its attendant advancement of commerce known before the American Revolutionary War. With their victory and independence, the fledgling federal government found itself sovereign over an area stretching along the Atlantic seaboard from New Hampshire to Georgia, and as far inland as the Mississippi River; it encompassed an area exceeding that of any western European nation of the time, with which it intended to trade, but without a competitive national infrastructure. While the coasting trade was relatively developed, the nation possessed limited transportation and communication lines with its interior, other than its recognized and exceptionally advantageous interior river systems and their interconnecting portages. With state sovereignty already established under the Confederation in the original states, for their new lands the Congress of the Confederation would set new precedent with the Northwest Ordinance concerning ownership of the lands, with known transportation routes as "common highways and forever free."[1] The need for internal improvements of these internal natural resources was widely recognized then; seen in a similar developmental light more than a century later, the preliminary report of the Inland Waterways Commission in 1908 provides a unique perspective on historical events. It notes: "The earliest movement toward developing the inland waterways of the country began when, under the influence of George Washington, Virginia and Maryland appointed commissioners primarily to consider the navigation and improvement of the Potomac; they met in 1785 in Alexandria and adjourned to Mount Vernon, where they planned for extension, pursuant to which they reassembled with representatives of other States in Annapolis in 1786; again finding the task a growing one, a further conference was arranged in Philadelphia in 1787, with delegates from all the States. There the deliberations resulted in the framing of the Constitution, whereby the thirteen original States were united primarily on a commercial basis —the commerce of the times being chiefly by water."[2]

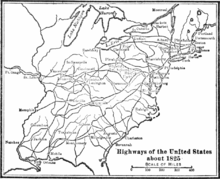

In the first twenty years, even as the population grew westward crossing the Appalachian Mountains with the admission of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio and then doubled in size by 1803, the only means of transportation between the interior lands and the coastal states remained on water, by canoe, boat (e.g. keelboat flatboat) and ship, or over land on foot and by pack animal. Recognizing the success of Roman roads in unifying that empire, political and business leaders in the United States began to construct roads and canals to connect the disparate parts of the nation.[3]

Toll roads

Early toll roads were constructed between some commercial centers and were owned by joint-stock companies that sold stock to raise construction capital, like Pennsylvania's 1795 Lancaster Turnpike Company. While transportation needs were universally recognized, in 1808 Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin's Report on the Subject of Public Roads and Canals suggested that the federal government should fund the construction of interstate turnpikes and canals, but many Anti-Federalists opposed the federal government assuming such a role. The British coastal blockade in the War of 1812 and an inadequate internal capability to respond, demonstrated the United States' reliance upon such overland roads for military operations as well as for general commerce.[4] Construction on the westward National Road began in 1815 at Cumberland, Maryland and it reached Wheeling, Virginia by 1818; by 1824 private tollways connected Cumberland eastward with commercial and port cities. Further westward extensions were constructed to Vandalia, Illinois, but financial crisis ultimately prevented its planned western extension to the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Nevertheless, the road became a primary overland route over the Appalachian Mountains and the gateway for the surge of westward-bound settlers and immigrants, which followed these continental wars.

Canals

Canal companies had also been chartered in the states, and like turnpikes, these early canals were constructed, owned, and operated by private joint-stock companies. Of all the canals projected for construction, only three were completed when the War of 1812 broke out; these were the Dismal Swamp Canal in Virginia, the Santee Canal in South Carolina, and the Middlesex Canal in Massachusetts. Later canal works would give way to larger projects and funding by the individual states.

After the war, New York ushered in a new era in internal communication by authorizing the construction of the Erie Canal in 1817. Proposed by Governor of New York De Witt Clinton, the Erie was the first canal project undertaken as a public good to be financed at the public risk through the issuance of bonds.[5] When the project was completed in 1825, the canal linked Lake Erie with the Hudson River through 83 separate locks and over a distance of 363 miles (584 km).

This bold bid for the western trade to their north alarmed the competing merchants of Philadelphia, since the completion of the National Road also threatened to divert much of their traffic south to Baltimore. In 1825, the legislature of Pennsylvania grappled with the problem by projecting a series of canals which were to connect its great seaport with Pittsburg on the west and with Lake Erie and the upper Susquehanna on the north.[6] The success of the Erie Canal spawned a boom of other canal-building around the country; over 3,326 miles of man-made waterways were constructed between 1816 and 1840.[7] Small towns like Syracuse, New York, Buffalo, New York, and Cleveland, Ohio located along major canal routes boomed into major industrial and trade centers, while exuberant canal-building pushed some states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana to the brink of bankruptcy.[8]

Political differences

Since their beginning, the national government had funded and constructed improvements along their coastline; this began with the founding of the Corps of Engineers (USACE), as part of the Army during the revolution, and many politicians wanted them to contribute to both military construction and works "of a civil nature." Before 1800, the Corps supervised the construction of coastal fortifications, but they also constructed lighthouses, helped develop jetties and piers for harbors, and carefully mapped the changing navigation channels. Although temporarily downsized following that war, it was reestablished in 1802, and the Corps of Engineers began constructing and repairing fortifications, in Norfolk and New Orleans. The fortification appropriations proliferated during the five years of diplomatic tension that preceded the War of 1812; these substantially expanding the system of fortifications protecting New York Harbor and convinced the commanders of the British navy to avoid attacking that strategic location. Following the war, the United States soon developed an expanded system of more modern fortifications to provide the first line of land defense against the threat of attack from European powers.[9] Outside of defense issues however, the federal power over domestic "internal improvements", away from the coasts and among the states, did not gain political consensus. Federal assistance for "internal improvements" evolved slowly and haphazardly—the product of contentious congressional factions and an executive branch generally concerned with avoiding unconstitutional federal intrusions into state affairs.[10]

In Federalist President John Adams' first message to Congress, he advocated not only the construction of roads and canals on a national basis but also the establishment of observatories and a national university. Later, in 1806 Democratic-Republican President Jefferson also had recommended many internal improvements for Congress to consider, including the creation of necessary amendments to the Constitution to allow themselves such powers. Adams did not share Jefferson's view of the limitations of the Constitution. In much alarm Jefferson suggested to Madison the desirability of having Virginia adopt a new set of resolutions, bottomed on those of 1798, and directed against the acts for internal improvements.

The magnitude of the transportation problem was such, however, that neither individual states nor private corporations seemed able to meet the demands of an expanding internal trade. As early as 1807, Albert Gallatin had advocated the construction of a great system of internal waterways to connect East and West, at an estimated cost of $20,000,000. But the only contribution of the national government to internal improvements during the Jeffersonian era was an appropriation in 1806 of two percent of the net proceeds of the sales of public lands in Ohio for the construction of a national road, with the consent of the states through which it should pass. By 1818 the road was open to traffic from Cumberland, Maryland, to Wheeling, West Virginia.[11]

In 1816, with the uneven experiences of the war quite evident, no well-informed statesman could shut his eyes to the national aspects of the problem. Even non-federalist President Madison invited the attention of Congress to the need of establishing "a comprehensive system of roads and canals". Soon after Congress met, it took under consideration a bill drafted by Calhoun which proposed an appropriation of $1,500,000 for internal improvements. Because this appropriation was to be met by the moneys paid by the National Bank to the government, the bill was commonly referred to as the "Bonus Bill". But on the day before he left office, Madison vetoed the bill because he felt it was unconstitutional. The policy of internal improvements by federal aid was thus wrecked on the constitutional scruples of the last of the Virginia dynasty. Having less regard for consistency, the House of Representatives recorded its conviction, by close votes, that Congress could appropriate money to construct roads and canals, but did not have the power to construct them. The only direct aid of the national government to internal improvements remained various appropriations, amounting to about $1,500,000 for the Cumberland Road.[12]

As the country recovered from financial depression following the Panic of 1819, the question of internal improvements again forged to the front. In 1822, a bill to authorize the collection of tolls on the recently completed Cumberland Road was vetoed by President James Monroe. In an elaborate essay, he set forth his views on the constitutional aspects of a policy of internal improvements. Congress might appropriate money, Monroe admitted, but it might not undertake the actual construction of national works nor assume jurisdiction over them. For the moment the drift toward a larger participation of the national government in internal improvements was stayed. The situation would change dramatically two years later however, with the Judicial Branch of government weighing in on related constitutional questions and ruling on them with some finality.

It should be pointed out that improvements sought were generally upon public lands under the exclusive jurisdiction of National Government not internal State lands.

Initial resolution

In March 1824 the Supreme Court ruled on Gibbons v. Ogden, in what would become a landmark decision; the Court held that the power to regulate interstate commerce was granted to Congress by the Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution. The Court went on to conclude that Congressional power over commerce should extend to the regulation of all aspects of it, overriding state law to the contrary.

In the debate that followed, no one pleaded more eloquently for a larger conception of the functions of the national government than Speaker of the House Henry Clay, the foremost proponent of the 'American System'. He called the attention of his hearers to provisions made for coast surveys and lighthouses on the Atlantic seaboard and deplored the neglect of the interior of the country. Of the other presidential candidates, Senator and war-hero Andrew Jackson voted for the General Survey Act, as did Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, who left no doubt in the public mind that he did not reflect the narrow views of his New England region on this issue. William H. Crawford felt the constitutional scruples which were everywhere being voiced in the South, and followed the old expedient of advocating a constitutional amendment to sanction national internal improvements.[13]

Shortly thereafter, Congress passed two important laws that would set a new course concerning federal involvement in "internal improvements". In April Congress passed the General Survey Act, which authorized the president to have surveys made of routes for roads and canals "of national importance, in a commercial or military point of view, or necessary for the transportation of public mail;"[10] this is sometimes referred to as the first "Roads and Canals" Act.[14] It authorized the survey of waterways to designate those "capable of sloop navigation." The second act, "An Act to Improve the Navigation of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers,"[14] was passed in May; it appropriated $75,000 to improve navigation on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers by removing sandbars, snags, and other obstacles; the second act is often called the first rivers and harbors legislation. The president assigned responsibility for the road, canal and waterway surveys as well as the navigation improvements to the Corps of Engineers. This legislation marked the beginning of the USACE's continuous involvement in domestic civil works.[10]

In 1826 Congress expanded the army engineers' workload and the pace of improvements. The new legislation, authorized the president to have river surveys made to clean out and deepen selected waterways and to make various other river and harbor improvements; it also was the first legislation of this type to combine authorizations for both surveys and projects, thereby establishing the pattern for future work.[10]

Some political differences did remain; in March, 1826, the Virginia general assembly declared that all the principles of their earlier resolutions applied "will full force against the powers assumed by Congress" in passing acts to further internal improvements and to protect manufacturers. That the John Quincy Adams administration would meet with opposition in Congress was a foregone conclusion.[15]

Further reading

- John Lauritz Larson, Internal Improvement: National Public Works and the Promise of Popular Government in the Early United States (2001). University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 978-0-8078-4911-8.

- Archer B. Hulbert, The Paths of Inland Commerce, A Chronicle of Trail, Road, and Waterway, Volume 21, Chronicles of America Series. Editor: Allen Johnson, (1921)

See also

References

- ↑ s:Northwest Ordinance. Art. 4:"The navigable waters leading into the Mississippi and St. Lawrence, and the carrying places between the same, shall be common highways and forever free, as well to the inhabitants of the said territory as to the citizens of the United States, and those of any other States that may be admitted into the confederacy, without any tax, impost, or duty therefor."

- ↑ Introductory note to Section 17, [portions of the Gallatin Report (1808)]

- ↑ Cowan 1997, pp. 94

- ↑ Cowan 1997, pp. 98

- ↑ Cowan 1997, pp. 102

- ↑ Johnson, Allen (1915), Union and Democracy, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company, p. 255–256

- ↑ Cowan 1997, pp. 104

- ↑ Cowan 1997, pp. 104

- ↑ The Beginnings to 1815, Corps of Engineers

- 1 2 3 4 Improving Transportation, United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)

- ↑ Johnson 1915, pp. 256

- ↑ Johnson 1915, pp. 257–258

- ↑ Johnson 1915, pp. 309–310

- 1 2 Timeline: Development of US Inland Waterways System, Coosa-Alabama River Improvement Association, Inc.

- ↑ Johnson 1915, pp. 319–320