History of the Astor House Hotel (Shanghai) 1900–22

The history of the Astor House Hotel, Shanghai 1900–1922,from its purchase by Auguste VernonHongkong from Ellen Jansen in 1900, to its sale to Hotels Limited in May 1922, provides an insight into the history of China itself. According to Rob Gifford, "The Astor House Hotel has witnessed the whole sweep of China's emergence into the modern world, from English opium running in the 1840s through the tea dances of polite society in the 1920s and to the excesses of Maoist China in the 1960s."[1]

Background (1900–1901)

On 1 November 1900, American Mrs Ellen McGrath Jansen, who had owned it since 1873, sold the Astor House Hotel for 175,000 taels (about US$130.000)[2] to Frenchman, M. Auguste Vernon.[3] Vernon already owned a hotel in Hankow,[4] and had previously managed the Hotel Bella Vista in Macau from its opening on 1 July 1890 until he left due to serious illness.[5] He retained all of the principal staff,[3] including the manager, Mr. Loureiro.[6]

At that time of the change of ownership, the Hotel was considered the first first-class hotel in Shanghai.[7] and "the best hotel in all the Orient",[8] One traveller indicated in 1900, "the Astor-House Hotel at Shanghai, it might be called European with a few Chinese characteristics. We of course had Chinese to wait on us here".[9] Vernon introduced several improvements, including a series of "Elite Dinners" accompanied by the Shanghai Municipal Symphony.[10] Vernon added a suite of eighteen bedrooms and saloons to the Hotel.[11] In 1901 the first telephones were installed in Shanghai, with the Astor House having the first telephone used.[12] In the first Yellow Pages telephone directory published in Shanghai, its number was "200". The North-China Herald praised the Astor House Hotel in January 1902: "it is a great thing that we have at last in Shanghai a hotel which is a credit to the place, and whose vast improvement has stimulated its rivals to renewed efforts to satisfy the travelling and homeless public".[13] However, later

In the first six months of 1901, the Astor Astor House Hotel had generated $90,000.61 profit, while its sister hotel in Hankow made just over $10,000.[14]

The Astor House Hotel Company (1901–1915)

Auguste Vernon era (1901–1902)

In July 1901, Vernon privately floated the Astor House Hotel Co. Ltd. with a capital of $450,000.[15] 4,500 shares were issued for $100 each, and were fully subscribed with Vernon or his nominees taking 4,494 shares,[16] with the remaining shares purchased by six separate individuals.[17] The shares were soon trading for up to $300 each.[18] The Astor House Hotel Ltd. was "incorporated under the Company Ordinances of Hong Kong",[19] with Vernon becoming the managing director.[20]

Later that month, as a response to the severe shortage of accommodation in the rapidly growing International settlement, Vernon was able to convince the company to negotiate an extension of the current nine-year lease of the hotel and its property with the Land Investment Company for an additional twenty-one years,[17] of the entire block, which included all the Chinese shops at the rear of the hotel, thus greatly expanding its holding but also increasing substantially the company's debt.[15][20] Vernon intended to demolish the Chinese shops to allow the construction of a new three-storied wing containing 250 rooms, thus increasing its capacity to 300 rooms, with the ground floor of the new wing to provide first class accommodation for retail stores.[21] Debentures with a return of 6% were issued in July 1901 to finance the expansion of the hotel,[22] with the expectation that the increased number of rooms would generate a surplus of income to repay the dentures expeditiously.[23]

In 1902, after less than two years of leadership, Vernon retired because of ill-health, and left owing the company "a considerable sum of money".[24] By 1904, Vernon was living in Tangku (Tanggu), and was the owner of the steamship George, which was seized that year off Liaotishan as a prize of war by the Empire of Japan, after transferring goods to Russia during the Russo-Japanese War.[25] Subsequently Vernon was manager of the Hotel de France and from 1916 the Keihin Hotel in Kamakura, Japan.[26]

Louis Ladow (1903–1904)

As Vernon had planned, the Chinese shops that occupied the newly leased property at the rear of the existing hotel were demolished. However, the new northern section of the hotel contained only 120 rooms, less than half of the number that Vernon had envisaged.[20] An outbreak of cholera in the city resulted in few guests when the northern wing was opened in November 1903. It was managed originally by "an eccentric American" octaroon,[27] Louis Ladow (died in China on November 20, 1928),[28] who had been imprisoned in Folsom Prison,[29] who subsequently built the Grand Carleton Hotel in Shanghai in 1920.[30] Under Ladow's supervision, his bartenders served "the finest cocktails in the Far East", a reputation it maintained through the 1930s.[31]

A. Haller (1904)

In 1904, the Hotel was considered "by far the best hotel in the whole of the East, including Japan."[32] At this time, Mr A. Haller was the manager.[33] About this time, the Hotel's managers wrote letters "complaining to the foreign-run Shanghai Municipal Council about "natives," "coolies" and "rickshaws" making too much noise for patrons to bear."[34]

Captain Frederick W. Davies (1906–1907)

By July 1906, retired British naval officer Captain Frederick W. Davies (born about 1850; died 16 January 1935 in Shanghai),[35] who had previously been a sea captain on the NYK European Service, and associate manager of the Grand Hotel in Yokohama,[36] had become manager of the Astor House,[37] and "a more genial and hospitable gentleman never carried out the duties of that position."[38] Room rates were between $7 and $10 per day (Mexican).[39] The hotel employed 254 people, with each hotel department "under special European supervision".[40] The 1904 announcement of the rebuilding of the Central Hotel (reopened in 1909 as the Palace Hotel) as a luxury hotel on the Bund,[41] and the demolition of the nearby Garden Bridge, and construction of the current Waibaidu Bridge in 1907, which involved the resumption of part of the Astor House Hotel's property, forced the owners of the Astor House Hotel to begin extensive renovations.[42]

Walter Brauen (1907–1910)

From February 1907, the hotel's manager was Swiss citizen Mr. Walter Brauen,[43] a skilled linguist who had been recruited from Europe.[44] The existing hotel was described as "the leading hotel of Shanghai...., but has an unpretentious appearance."[45] The company decided to embark on a completely new hotel, "fitting of Shanghai's growth and importance" and "better than any in the Far East."[46] In 1908, before any reconstruction or renovations, the Astor House was described in glowing terms:

Leading straight from the entrance to the main residential portion of the house is a long glass arcade. Upon one side of this are the offices, where the clerks and commissioners will attend promptly and courteously to every want; upon the other is a luxuriously furnished lounge, and, adjoining this, the reading, smoking, and drawing rooms. The dining room has accommodations for five hundred persons. It is lighted with hundreds of small electric lamps, whose rays are reflected by the large mirrors arranged around the walls, and when dinner is in progress, and the band is playing in the gallery,the scene is both bright and animated. There are some two hundred bedrooms, each with a bathroom adjoining, all of which look outward, facing either the city or the Whangpoo River. Easy access is gained to the various floors upon which they are situated by electric elevators. The hotel...generates its own electricity and has its own refrigerating plant."[40]

Architects and civil engineers Davies & Thomas (established in 1896 by Gilbert Davies and C.W, Thomas), were responsible for the re-building of the three principal wings of the Astor House Hotel.[47] The Astor House Hotel was to be restored to a neo-classical Baroque structure,[48] making it once again "the finest hotel in the Far East".[41] The new addition (the Annex) was based on plans drawn by "Shanghai's leading architects of the time",[42] British architects and civil engineers, Brenan Atkinson and Arthur Dallas (born 9 January 1860 in Shanghai; died 6 August 1924 in London), established as Atkinson & Dallas in 1898.[49] After the death of principal architect Brenan Atkinson in 1907,[50] he was replaced by his brother, G. B. Atkinson.[51] The intention was to rebuild the hotel "on modern lines", using reinforced concrete as the primary building material.[52] Included in the plans were: "the dining room, facing the Soochow Creek, is to be extended along the whole front of the building. Winter gardens are being constructed, the writing and smoking rooms, and the private bar and billiard room will be enlarged and the kitchen placed upon the roof."[53] A new reinforced concrete wharf measuring 1,180 feet (360 m) long and 200 feet (61 m) wide was also constructed.[52]

Prior to the new construction, future US President William Howard Taft, then US Secretary of War, and his wife, Helen Herron Taft,[54] were honoured at a banquet organised by the American Association of China in the large dining room at the Astor House Hotel in Shanghai on 8 October 1907, with over 280 in attendance; it was, at that time, "the largest affair of the kind ever given in China."[55] During the dinner, Taft made a significant speech on the relationship between the United States and China, and supporting the Open Door foreign policy previously advocated by John Hay.[56] Organized Sunday School work in China was born at Shanghai on 4 May 1907. "This beginning of Sunday-school history in China took place in Room 128 of the Astor House, Shanghai, occupied at that time by Mr. [Frank A.] Smith."[57]

The opening of a tram line in March 1908 over the new Garden bridge along Broadway (now Daming Lu) past the Astor House Hotel by the Shanghai British Trolley Company,[58] greatly increased both access and business.[45] Also in this period, the first western movies shown in China were shown at the Astor House Hotel.[59] On 9 June 1908, a motion picture with some sound was first shown in China in the open air in the hotel's garden.

Construction finally commenced in November 1908, and was scheduled to be completed by July 1909.[46] However, delays postponed completion until November 1910.[46]

In September 1910, days after the annual meeting of the Astor House Hotel Co., Brauen "ran off with a huge chunk of hotel funds just three months before the hotel opened, six months behind schedule, in January 1911."[46] A total of $957 had been embezzled by Brauen.[60] A warrant for his arrest was issued by the Mixed Court of Shanghai,[60] but Brauen had already left Shangha on a Japanese steamship.[61] Brauen was spotted in Nagasaki on Thursday, 14 September 1910, but evaded capture.[46][61] At the annual meeting of Astor Hotel Co. in September 1911, Mr. F. Airscough, the chairman, reported that Brauen had been "a thoroughly capable hotel Manager" but who had "left our employment under most regrettable circumstances".[44]

Re-opening (1911)

Costing $360,000,[62] the restoration was completed in December 1910,[63] and the official opening was on Monday, 16 January 1911.[64] The North-China Herald reported:

The enduring impression of a city is largely given by the buildings that first catch the eye. The new Astor House Extension will greatly assist in bearing in upon the visitor that he is approaching no mean city. Favoured by its site, it stands out boldly and inspires a belief in the future of a city that can support such a huge caravanserai, in addition to others. The Shanghai resident regards it with equal admiration and also with a sense of personal pride. That gigantic edifice stands where, in the memory of many still living, the swamp-birds called defiantly to the struggling settlement that was finding its feet on the other side of the creek. It personifies to the resident the verification of the brightest dreams that in the old days the most daring dared to dream. A huge, but stately seal has in a sense been set upon the city's aspirations, and it stands at once as an emblem of accomplishment and an example for emulation.[64]

Advertising itself as the Waldorf Astoria of the Orient’, its new 211-room building, with a 500-seat dining room.[41] Another advertisement described the Astor House Hotel in even more glowing terms: "Largest, Best and Most Modern Hotel in the Far East. Main Dining Room Seats 500 Guests, and is Electrically Cooled. Two hundred Bedrooms with Hot and Cold Baths Attached to Each Room. Cuisine Unexcelled; Service and Attention Perfect; Lounge, Smoking and Reading Rooms; Barber and Photographer on the Premises. Rates from $6; Special Monthly Terms."[65] An advertisement in Social Shanghai in 1910 bragged, "The Astor House Hotel is the most central, popular and modern hotel in Shanghai.[66] At the time of its re-opening in January 1911, the refurbished Astor House Hotel was described as follows:

The building has five storeys and attics on the Whangpoo Road frontage and four storeys on the Astor Road side. On the ground floor, at the corner of Whangpoo Road and the Broadway, is a handsomely appointed public bar-room and buffet, 59 ft (18 m). by 51 ft (16 m) .; in the centre, with main entrance from Whangpoo Road, is a magnificent lounge ball, 70 ft (21 m). by 60 ft (18 m) ., and at the East end are the Hotel office and the manager's office, with the secretary's office, in mezzanine, above the latter. The basement fronting Astor Road contains store-rooms, the steam-heating apparatus, and motor fire-pump. The grand staircase, with marble dado and red panels on white background, leads upward to passenger lifts, a ladies cloak room, a very prettily furnished ladies' sitting room, a reading room with several comfortable sofas and easy chairs upholstered in leather, a private buffet with a polished teakwood bar, and a large billiard room. Farther up the grand staircase is the main dining hall, almost the whole length of the building with a gallery and verandah on the second floor and well lighted by a barreled ceiling of glass. On the Astor Road side is a handsome banqueting hall and reception rooms, both decorated in ivory and gold, and six private dining rooms. There were six service elevators, bedrooms with private sitting rooms, and luxury suites under the dome.[64]

Additionally, the Hotel now had a 24-hour hot water supply, some of the earliest elevators in China, and each of the 250 guest rooms had its own telephone, as well as an attached bath. A major feature of the reconstruction was the creation of the Peacock Hall, "the city's first ballroom",[67] "the most commodious ballroom in Shanghai".[68] The newly restored Astor House Hotel was renowned for its lobby, special dinner-parties, and balls."[68] According to Peter Hibbard, "[D]espite their architectural bravura and decorative grandeur, the formative years of both the Palace and Astor House Hotels were overshadowed by an inability to cater for the fast changing tastes of Shanghai society and her visitors".[69] In 1911, John H. Russell, Jr. told his daughter, the future Brooke Astor, that the Hotel offered "the finest service in the world", and that in response to her question about "a man dressed in a white skirt and blue jacket beside every second door", was told by Russell: "They are the 'boys'. ... When you want your breakfast or your tea, just open the door and tell them."[70]

William Logan Gerrard (1910–1915)

In October 1910, Scotsman William Logan Gerrard, who was a long-time resident of Shanghai, was appointed the new manager,[71] but severe illness forced him into hospital for several weeks, before being invalided home temporarily.[44] Soon after his release from the hospital, Gerrard married Gertrude Heard on Tuesday 19 July 1911 at the St. Joseph's Roman Catholic Church in the French Concession. That evening, they departed on their honeymoon in the USA and Scotland, and returned to Shanghai early in 1912.[72] The Secretary of the Hotel, Mr. Whitlow, was appointed acting manager, but was soon replaced by Mr. Olsen.[44]

On 3 November 1911, during the Xinhai Revolution that would lead to the collapse of the Qing dynasty in February 1912, an armed rebellion began in Shanghai, which resulted in the capture of the city on 8 November 1911, and the establishment of the Shanghai Military Government of the Republic of China, which was formally declared on 1 January 1912. Business proceeded for the Astor House Hotel, where rooms were available from $6 to $10 per night.[73] However, the effects of the Revolution and the long absence of Gerrard resulted in a three-month operating loss of $60,000. On 30 June 1912, a "serious crisis" confronted the shareholders of the Astor House Hotel Company. While praise for the renovations was almost universal, they strained severely the Hotel's finances.[74] The Hotel's bank refused to issue the funds needed to pay interest to the debenture holders, forcing an extraordinary meeting with the trustees of the note holders.[75] The interest was finally paid after mortgaging the Astor Garden (B.C. Lot 1744), the foreshore property between Whangpoo Road and the Suchow Creek, for 25,000 taels (US$33,333.33).[62]

On 11 December 1913, the Astor House Hotel hosted a banquet for both the New York Giants of John McGraw and Chicago White Stockings of Charles Comiskey baseball teams, which included Christy Mathewson and Olympian Jim Thorpe, who were touring the world playing exhibition games.[76] This transnational tour was led by Albert Goodwill Spalding, owner of the White Stockings, "professional baseball's most influential figure."[77] At that time, "No hotel in Shanghai, and few in the world, surpassed the Astor House Hotel. A handsome and impressive stone edifice of arched windows and balconies, the hotel stood six stories high and sprawled over three acres of land near the heart of the city.[78] On 29 December 1913 the first sound film in China was shown at the Hotel. At this time there were still restrictions on Chinese entering the Astor House Hotel.[79]

At the annual meeting of the Astor House Hotel Company held at the hotel in October 1913, the directors revealed plans to increase profit by another reconstruction,[80] including the construction of a new theatre seating 1,200 people to replace Astor Hall, which seated only 300; additional luxury suites; and also a winter garden.[81]

Mary Hall, who stayed at the Astor House in April 1914, described her experience:

The Astor House, which since I was here last, seventeen years ago, had outgrown all recognition....I entered the spacious social hall flanked with cigar, sweets, scent and other stalls....[I]nside the hotel it was easy to imagine ones self in London or New York. The idea is soon dissipated when you find yourself following a man clad in bath-room slippers and shirt to the feet, the whiteness of which is relieved by a long black pigtail hanging down his back. He bows and smiles as he unlocks a door and shows you to your room, which is light and airy, with a bath-room attached. The dining-room was a gorgeous scene in the evening...The room is long, and the prevailing colours buff and white: down the centre are very handsome Chinese inlaid pillars on which, during the hot months, electric fans are worked. A gallery runs down either side, and in the busy season is also filled with tables. A band plays nightly....'Boys' moved hither and thither dressed in long blue shirts over which were worn short white sleeveless jackets, the latter obviously full dress, as they were dispensed with at breakfast or tiffin. Soft black shoes over white stockings, and legs swathed with dark felt were the finishing touches of a picturesque uniform.[82]

During 1914, the Astor Gardens, the portion of the hotel grounds at the front of the Hotel known as "the foreshore" that had stretched to the Suzhou Creek, was sold to allow the construction of the consulate of the Empire of Russia immediately in front of the Hotel.[83] By October 1914, the Hotel's financial position had improved sufficiently to allow the shareholders to approve the renovation plans, which included demolishing the old dining room and kitchen to create eight shops that could be leased, and first class bedrooms and small apartments; construction of a new dining room in the centre of the hotel; relocation of the kitchen on the top floor to allow the conversion to bachelor's bedrooms; and conversion of part of the bar and billiard room into a grill room.[84]

Despite the renovations, financial difficulties persisted that resulted in the trustees for the debenture holders foreclosing on the Hotel in August 1915.[85] In September 1915, the trustees subsequently sold the Astor House Hotel Company Limited and all of its property and assets, including over 10 mow of land, to Central Stores Limited, owners of the Palace Hotel, for 705,000 taels.[85] With the change of ownership, Gerrard's services were no longer required.

Central Stores Ltd. (1915–1917) and The Shanghai Hotels Limited (1917–1923)

Central Stores Ltd. (renamed The Shanghai Hotels Limited in 1917) was owned 80% by Edward Isaac Ezra (born 3 January 1882 in Shanghai; died 16 December 1921 in Shanghai),[86] the managing director of Shanghai Hotels Ltd., the largest stockholder,[87] and its major financier,[88] At one time, Ezra was "one of the wealthiest foreigners in Shanghai".[89] According to one report, Ezra amassed a vast fortune estimated at from twenty to thirty million dollars primarily through the importation of opium[90] and successful real estate investment and management in early twentieth century Shanghai.[91] The Kadoorie family, Iraqi Sephardic Jews from India,[92] who also owned the Palace Hotel at number 19 The Bund, on the corner with Nanjing Road, had a minority share holding in the Astor House Hotel.

Captain Harry Morton (1915–1920)

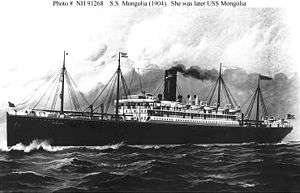

Despite some shareholder opposition, in March 1915, Captain Henry "Harry" Elrington Morton (born 12 May 1869 in Clonmel, Ireland; died 2 October 1923 in Manila)[93] a "staunch Britisher"[94] who had become a naturalised American citizen,[95] a master mariner who had first gone to sea at age 14,[96] formerly of the Royal Navy,[97] a Royal Arch freemason,[98] who "had been coming to Shanghai for twenty years",[99] was appointed managing director, with responsibility for managing Central Stores' three Shanghai hotels, including the Astor House, with a salary of $900 a month, plus board and lodging.[100] Morton was "a retired ship captain who ran it as a ship, the hotel had corridors painted with portholes and trompe l'oeil seascapes and rooms decorated like cabins; there was even a "steerage" section with bunks instead of beds at cheaper rates."[101] American journalist John B. Powell, who first arrived in Shanghai in 1917 to work for Thomas Franklin Fairfax Millard, the founder of what later became The China Weekly Review, described his new accommodation at the Astor House Hotel: "the Astor House in Shanghai consisted of old three- and four-story brick residences extending around the four sides of a city block and linked together by long corridors. In the center of the compound was a courtyard where an orchestra played in the evenings. Practically everyone dressed for dinner, which never was served before eight o'clock.[102] According to Powell, "Since most of the managers of the Astor House had been sea captains, the hotel had taken on many of the characteristics of a ship."[103] While at that time the Hotel charged about $10 a day Mexican for accommodation,[104] "a room in the "steerage" ... [cost] $125 a month, including meals and afternoon tea. That figured out at about $60 in United States currency."[103] According to Powell,

the "steerage" section ... consisted of single rooms and small suites at the back of the hotel. The section resembled an American club, because practically all of the rooms and suites were occupied by young Americans who had come out to join the consulate, commercial attaché's office, or business firms whose activities were undergoing rapid expansion. Sanitary arrangements left much to be desired. There was no modern plumbing. The bathtub consisted of a large earthenware pot about four feet high and four feet in diameter....The Chinese servant assigned to me would carry in a seemingly endless number of buckets of hot water to fill the tub in the morning.[105]

In 1915, soon after taking control of the Astor House Hotel, Ezra decided to add a new ballroom.[106] The new ballroom, designed by Lafuente & Wooten, was opened in November 1917.[107]

In July 1917, the assistant manager was Mr. Goodrich.[108] Around the end of World War I, the Sixty Club, a group of sixty men-around-town (a mixture of actors and socialites), and their dates would meet at the Astor House each Saturday night.[109] Shanghai was considered the "Paradise of Adventurers", and the "ornate but old-fashioned lobby" of the Astor House was considered its hub.[110] The lobby was furnished with the heavy mahogany chairs and coffee tables.[111] By 1918 the lobby of the Astor House, "that amusing whispering gallery of Shanghai",[112] was "where most business is done" in Shanghai.[113] After China signed the International Arms Embargo Agreement of 1919, "sinister-looking German, American, British, French, Italian, and Swiss arms dealers appeared in the lobby of the Astor House . . . to dangle fat catalogs of their wares before the eager eyes of any buyers."[114] In 1920, the lobby "with its convivial atmosphere, presents to the visitor a welcome oasis, where congregate travelers from afar to chat pleasantly."[115] Another recorded: "The effervescence at the Astor is more tangy than elsewhere. All the latest scandal of the town is an old story in its lobbies almost before it occurs."[116] Powell added: "At one time or another one saw most of the leading residents of the port at dinner parties or in the lobby of the Astor House. An old resident of Shanghai once told me, "If you sit in the lobby of the Astor House and keep your eyes open you will see all of the crooks who hang out on the China coast."[102] According to Ron Gluckman, "Opium was commonplace, says one woman who lived in Shanghai before World War II. 'It was just what you had, after dinner, like dessert.' Opium and heroin were available via room service at some of the old hotels like the Cathay and Astor, which offered drugs, girls, boys, whatever you wanted."[117]

In 1919, Zhou Xiang (周祥),[118] "an Astor House bellboy, rewarded for recovering a Russian guest's wallet with its contents, spent a third of it on a car. That car became Shanghai's first taxi, and spawned the Johnson fleet, now known as the Qiangsheng taxi",[119] which is "now ranked number-two by the number of taxis in the city behind Dazhong. The Shanghai government took over Qiangsheng after the Communists won the Chinese civil war in 1949".[120]

Despite an annual profit of $596,437 in the previous year, in April 1920, Morton was forced to resign as the manager of the Shanghai Hotels Companies, Ltd, due to a new British government Order in Council restricting management of British companies to British subjects.[121] Morton subsequently left Shanghai in May 1920 on board the steamer Ecuador.[121][122]

Walter Sharp Bardarson (1920–1923)

Morton was replaced by Canadian Walter Sharp Bardarson (born 20 September 1877 in Roikoyerg, Iceland); died 17 October 1944 in Alameda, California).[123] who became an American citizen after he resigned from the Astor House Hotel in June 1923.[124] A 1920 travel guide summarised the features of the Astor House: "Astor House Hotel 250 rooms all with attached baths, the most commodious ballroom in Shanghai, renowned for its lobby, special dinner-parties, and balls. Banquets a special feature, and a French chef employed. Up-to-date hairdressing salon and beauty parlor. Strictly under foreign supervision."[125]

Under the leadership of Edward Ezra, the Astor House Hotel made a handsome profit. Ezra, intended to build "the biggest and best hotel in the Far East, a 14-storey hotel with 650 huge luxury bedrooms, including a 1500-seat dining hall and two dining rooms", on Bubbling Well Road.[126] Tragically, Ezra died on Thursday, 16 December 1921.[127] In 1922, Sir Ellis Kadoorie, one of the prominent members of the board of the Hong Kong Hotel Company, died aged 57, thus curtailing their expansion plans.[128]

On 12 May 1922, Ezra's 80% controlling interest in The Shanghai Hotels Limited was purchased for 2.5 million Mexican dollars by Hongkong Hotels Limited,[129] "Asia's oldest hotel company",[130][131] which already owned the Hongkong Hotel, as well as the Peak, Repulse Bay, and Peninsular Hotels in Kowloon; Messrs. William Powells Ltd., a large department store in Hong Kong; the Hong Kong Steam Laundry; and three large parking garages in Hong Kong.[129]

References

- ↑ Gifford, Rob (2007). China Road: A Journey into the Future of a Rising Power. New York: Random House. p. 4. ISBN 0747593353.

- ↑ http://www.measuringworth.com/uscompare/

- 1 2 "The Transfer of the Astor House". North China Herald. 24 October 1900.

- ↑ "The Astor House Hotel Company, Limited". North China Herald. 24 July 1901.

- ↑ Denby, Elaine (1998). Grand Hotels: Reality and Illusion. Edinburgh: Reaktion Books. p. 210. ISBN 9781861890108.

- ↑ North China Herald|date=17 October 1900

- ↑ The North-China Herald (17 July 1901):6 (102).

- ↑ The World's Work: A History of our Time 3 (Doubleday, Doran and company, 1901):1963.

- ↑ J. Fox Sharp, Japan and America: Lecture (Todd, Wardell and Larter, 1900):13.

- ↑ North-China Herald (14 November 1900):30 (1046).

- ↑ "The Astor House Hotel Company, Limited", North-China Herald (24 July 1901):21 (165).

- ↑ The Astor House in Tientsin installed one of the first telephones in 1879. See Dikötter, 148.

- ↑ The North-China Herald (8 January 1902), quoted in William Arthur Thomas, Western Capitalism in China: A History of the Shanghai Stock Exchange (Ashgate, 2001):58.

- ↑ "The Astor House Hotel Company, Limited", North-China Herald (24 July 1901):20. In 2008, $90,000.00 from 1900 is worth: $2,380,500.00 using the Consumer Price Index. See Samuel H. Williamson, "Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1790 to Present," MeasuringWorth, 2009. URL http://www.measuringworth.com/uscompare/

- 1 2 North-China Herald (10 July 1901):5 (49).

- ↑ North-China Herald (17 July 1901):6 (102).

- 1 2 "The Astor House Hotel Company, Limited", North-China Herald (24 July 1901):20.

- ↑ North-China Herald (10 July 1901):5 (49) and 48 (92).

- ↑ Japan: Overseas Travel Magazine 19 (1930):47,49.

- 1 2 3 Hibbard, Bund, 213.

- ↑ North-China Herald (17 July 1901):5 (101)

- ↑ North-China Herald (10 July 1901):48 (92).

- ↑ "The Astor House Hotel Company, Limited", North-China Herald (24 July 1901):21.

- ↑ Hibbard, Bund, 213.

- ↑ "The George", North-China Herald (11 November 1904):17 (1077).

- ↑ North-China Herald (20 July 1918):9 (129).

- ↑ Hibbard, Bund, 213.

- ↑ U.S. Department of State, "Report of the Death of an American Citizen", see Dave Ellison, "Death of Mr. Louis Ladow in China", (15 August 2005),

- ↑ His sentence was remitted by US President Benjamin Harrison in May 1891. See The Record-Union (Sacramento, California) (1 May 1891):6, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015104/1891-05-01/ed-1/seq-6/

- ↑ Carl Crow, Foreign Devils in the Flowery Kingdom (1941):97; Jennifer Craik, Uniforms Exposed: From Conformity to Transgression (Berg, 2005):viii.

- ↑ Hibbard, Bund, 113-114.

- ↑ Henry James Whigham, Manchuria and Korea (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1904):223.

- ↑ The East of Asia Magazine: Special Educational Number (June 1904):136.

- ↑ Niv Horesh, "Rambling Notes: Tracing 'Old Shanghai' at the Futuristic Heart of 'New China', The China Beat (5 July 2009); http://thechinabeat.blogspot.com/2009/05/rambling-notes-tracing-old-shanghai-at.html

- ↑ The China Monthly Review 75 (1935):286. One source indicates his name was John Davies. See Marshall Pinckney Wilder, Smiling 'round the World (Funk & Wagnalls Co., 1908):83.

- ↑ North-China Herald (5 February 1904):31 (243).

- ↑ "R. v. G. Wilson, alias Hamilton", North-China Herald (6 July 1906):41ff.

- ↑ Wilder, 83. From 1 July 1907 Davies had superintended the construction of the Burlington Hotel at 173 (later re-numbered 1225) Bubbling Well Road, Shanghai (now the site of the JC Mandarin Shanghai Hotel at 1225 West Nanjing Road. See Damian Harper and David Eimer, "Lonely Planet Shanghai", 4th ed. (Lonely Planet, 2008):201). From September 1908 to at least July 1912 Davies was manager of Burlington Hotel. See See "Liu Men-tsor v. F. Davies", North-China Herald (5 October 1912):67 (69); North-China Herald (27 July 1912):63ff. From before August 1913 Davies operated the Woosung Forts Hotel, a small hotel in the Woosung region, that was almost completely destroyed in fighting between Japan and China in February 1932. See North-China Herald (9 August 1913):62 (440); "Mr Oldis' Story", Sydney Morning Herald (24 March 1932):11; Ping-jui Li, One Year of the Japan-China Undeclared War and the Attitude of the Powers (The Mercury Press, 1933):246; "Press: Covering the War", Time 19 (22 February 1932), http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,743233,00.html

- ↑ Arnold Wright and HA Cartwright, Twentieth Century Impressions of Hong Kong: History, People, Commerce, Industries & Resources (Lloyd's Publishing House, 1908):

Wikisource has original text related to this article: - 1 2 Wright & Cartwright, 686, 688.

- 1 2 3 The Hong Kong and Shanghai Hotels Ltd., "Tradition Well Served and Heritage Revisited", press release (21 November 2008):3; Edited from an essay by Peter Hibbard, September 2008; http://www.peninsula.com/Shanghai/en/Media_Room/~/media/C98B41A4C2FC49B2AD923D46229BB577.ashx (accessed 11 April 2009).

- 1 2 Peter Hibbard, "rockin’ the bund" (05 November 2007); http://shhp.gov.cn:7005/waiJingWei/content.do?categoryId=1219901&contentId=15068201

- ↑ "The Astor House Hotel Co. Ld.", North-China Herald (23 August 1907):19; Hibbard, Bund, 114; The Shanghai Times (20 May1908):1; Arnold Wright and HA Cartwright, Twentieth Century Impressions of Hong Kong: History, People, Commerce, Industries & Resources (Lloyd's Publishing House, 1908):358; https://archive.org/stream/twentiethcentury00wriguoft#page/358/mode/2up

- 1 2 3 4 "Astor House Hotel: Annual Meeting", North-China Herald (2 September 1911):29.

- 1 2 Arnold Wright and HA Cartwright, Twentieth Century Impressions of Hong Kong: History, People, Commerce, Industries & Resources (Lloyd's Publishing House, 1908):375; https://archive.org/stream/twentiethcentury00wriguoft#page/374/mode/2up

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hibbard, Bund, 114.

- ↑ Wright & Cartwright, 630, 632; Edward Denison and Guang Yu Ren, Building Shanghai: The Story of China's Gateway (Wiley-Academy, 2006):113; Arif Dirlik, "Architecture of Global Modernity, Colonialism and Places" in The Domestic and the Foreign in Architecture, eds. Ruth Baumeister and Sang Lee (010 Publishers, 2007):39.

- ↑ "浦江饭店". Pujianghotel.com. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ Wright & Cartwright, 628, 630; Banister Fletcher, Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture, ed. Dan Cruickshank, 20th ed. (Architectural Press, 1996):1228; Edward Denison and Guang Yu Ren, Building Shanghai: The Story of China's Gateway (Wiley-Academy, 2006):113; Arif Dirlik, "Architecture of Global Modernity, Colonialism and Places" in The Domestic and the Foreign in Architecture, eds. Ruth Baumeister and Sang Lee (010 Publishers, 2007):39.

- ↑ "Atkinson & Dallas", Dictionary of Scottish Architecture

- ↑ Wright & Cartwright, 628.

- 1 2 Concrete and Constructional Engineering 4 (1909):446.

- ↑ Wright & Cartwright, 630.

- ↑ Helen Herron Taft, Recollections of Full Years (Dodd, Mead & Company, 1914):314.

- ↑ Thomas F. Millard, "Taft's Significant Shanghai Speech: Regarded There as the Most Important, Internationally, of His Trip. Insures the "Open Door"", The New York Times (24 November 1907):8; http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9C06E7D6103EE033A25757C2A9679D946697D6CF

- ↑ Thomas F. Millard, "Taft's Significant Shanghai Speech: Regarded There as the Most Important, Internationally, of His Trip. Insures the "Open Door"", The New York Times (24 November 1907):8; http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9C06E7D6103EE033A25757C2A9679D946697D6CF; Ralph Eldin Minger, William Howard Taft and United States Foreign Policy: The Apprenticeship Years, 1900–1908 (University of Illinois Press, 1975):169.

- ↑ Frank A. Smith, "The Story of Organized Sunday School Work in China", in Philip E. Howard, Sunday-Schools the World Around: The Official Report of the World's Fifth Sunday-School Convention in Rome, May 18–23, 1907 (The World's Sunday-school Executive Committee, 1907):221.

- ↑ Xu Tao, "The Popularization of Bicycles and Modern Shanghai" Frontiers of History in China 3:1 (March 2008):130; http://www.springerlink.com/content/q8824vnj41q55lm2/fulltext.pdf

- ↑ "First Movies at Hotels: Movie Time at Grand Hotels." (14 November 2006); http://famoushotels.org/article/510 (accessed 13 April 2009).

- 1 2 North-China Herald (16 September 1910):52.

- 1 2 "Local and General News", North-China Herald (23 September 1910):10.

- 1 2 "Astor House Hotel", North-China Herald (31 August 1912):34.

- ↑ Richard Harpruder, Shanghai: The Way We Remember it (accessed 11 April 2009)

- 1 2 3 "The New Astor House Building", North-China Herald (20 January 1911):20 (130).

- ↑ DBHKer (2013-10-20). "Astor House Hotel - Shanghai - 1916 | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ Tess Johnston, The Last Colonies: Western Architecture in China's Treaty Ports; quoted in "Five-star legend", Shanghai Daily News (18 April 2005); http://english.eastday.com/eastday/englishedition/node20665/node20667/node22808/node45576/node45577/userobject1ai1026003.html (accessed 11 April 2009).

- ↑ "Hotel Uncovers Hidden Treasures" (7 May 2004)

- 1 2 George Ephraim Sokolsky, China, A Sourcebook of Information (Pan-Pacific Association, 1920).

- ↑ Hibbard, 3.

- ↑ Dong, 208.

- ↑ North-China Herald (12 October 1912):60; "The New Astor House Building", North-China Herald (20 January 1911):20 (130).

- ↑ North-China Herald (22 July 1911):46 (236).

- ↑ Carl Crow, The Travelers' Handbook for China (Dodd, Mead & Co., 1913):158.

- ↑ "Astor House Hotel Co., Ld.", North-China Herald (3 October 1914):38.

- ↑ "Astor House Hotel Co.", North-China Herald (12 October 1912):33.

- ↑ James E. Elfers, The Tour to End All Tours: The Story of Major League Baseball's 1913–1914 World Tour (U of Nebraska Press, 2003).

- ↑ Thomas W. Zeiler, "Basepaths to Empire: Race and the Spalding World Baseball Tour1", Journal of Gilded Age and Progressive Era 6:2 (April 2007); http://www.historycooperative.org/cgi-bin/justtop.cgi?act=justtop&url=http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jga/6.2/zeiler.html accessed (12 Apr. 2009).

- ↑ James E. Elfers, The Tour to End All Tours: The Story of Major League Baseball's 1913–1914 World Tour (U of Nebraska Press, 2003):125.

- ↑ North-China Herald (1 March 1913):66 (652).

- ↑ "Astor House Hotel Co.", North-China Herald (4 October 1913):46.

- ↑ "New Theatre in Shanghai", North-China Herald (11 October 1913):34.

- ↑ Mary Hall, A Woman in the Antipodes and in the Far East (Methuen, 1914):286.

- ↑ "Astor House Hotel Co., Ld.", North-China Herald (3 October 1914):38; Hibbard, 215.

- ↑ "Astor House Hotel Co., Ld.", North-China Herald (3 October 1914):38-39.

- 1 2 "The Central Stores", North-China Herald (18 September 1915):29.

- ↑ "Sudden Death of Mr. Edward Ezra", North-China Herald (17 December 1921):27 (767); Les Fleurs de L'Orient; http://www.farhi.org/genealogy/getperson.php?personID=I91406&tree=Farhi

- ↑ Hotel Monthly 28 (1920):53.

- ↑ Hibbard, 4.

- ↑ Tahirih V. Lee, Contract, Guanxi, and Dispute Resolution in China ( ):110.

- ↑ G. E. Miller, Shanghai: The Paradise of Adventurers (Orsay Publishing House Inc., 1937):153.

- ↑ Kathryn Meyer and Terry Parssinen, Webs of Smoke: Smugglers, Warlords and the History of the International Drug Trade (Rowman & Littlefield, 2002):40.

- ↑ Chiara Betta, "From Orientals to Imagined Britons: Baghdadi Jews in Shanghai", Modern Asian Studies 37 (2003):999-1023; http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=181381

- ↑ U.S. Passport Applications Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 - March 31, 1925 (M1490) Roll 0905 - Certificates: 115000-115249, 10 Sep 1919-11 Sep 1919. Application dated 22 July 1919; The China Weekly Review 26 (6 October 1923):218; Pacific Marine Review 20 (1923):528. On Friday, 20 July 1917, Morton married Mary Jane Free (born 29 June 1894 in USA), daughter of Mr Henry Free, at a private home at 53 Avenue Road, Shanghai. See Millard's Review of the Far East, Vol. 1 (1917); "Presentation to Captain H.E. Morton", North-China Herald (21 July 1917):36 (156); California Passenger and Crew Lists: Arrival Date: 27 July 1922 Ship Name: President Hayes Port of Arrival: San Francisco, California Port of Departure: Manila, Philippines Archive information (series:roll number): M1410:162.

- ↑ The Weekly Review of the Far East 21 (1922).

- ↑ Morton lived officially in the USA from 1890 to 1915, and was naturalised on 11 December 1905 in the Federal Court in San Francisco. Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 - March 31, 1925 (M1490); See Roll 0613 - Certificates: 41500-41749, 24 Oct 1918-25 Oct 1918 > Image 129

- ↑ "HIS PACIFIC LOG IS 720,000 MILES; Capt. Morton, Sailing There for 25 Years, Is Friendly with Typhoons", The New York Times (19 September 1910):7; The Cosmopolitan 50 (Schlicht & Field, 1910):59.

- ↑ The Navy List (H.M. Stationery Office., 1891):324; Charles Higham, Wallis: Secret Lives of the Duchess of Windsor (Sidgwick & Jackson, 1988):38; Powell, 9, 52.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons of the State of California at its ... Annual Convocation, Vols. 57-58 (1911):910.

- ↑ Morton had been commander of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company's Mongolia, which sailed between San Francisco and the Orient from 1904 until 1915. By 1910 Morton had crossed the Pacific Ocean 45 times as skipper of the Mongolia. See "HIS PACIFIC LOG IS 720,000 MILES; Capt. Morton, Sailing There for 25 Years, Is Friendly with Typhoons", The New York Times (19 September 1910):7; "Immigrant Ships: Transcribers Guild: SS Mongolia", http://www.immigrantships.net/1900/mongolia19100224.html; Pacific Marine Review 20 (1923):528; "S.S. Mongolia", http://www.atlantictransportline.us/content/45Mongolia.htm; E. Mowbray Tate, Transpacific Steam: The Story of Steam Navigation from the Pacific Coast of North America to the Far East and the Antipodes, 1867-1941 (Associated University Presses, 1986):36-37; Robert Barde, "The Scandalous Ship Mongolia", Steamboat Bill: Journal of The Steamship Historical Society of America 250 (Spring 2004):112-118; "Joseph Tape and the S.S. Mongolia"

- ↑ Central Stores, Limited", North-China Herald (18 March 1916):36-37.

- ↑ Stella Dong, Shanghai: The Rise and Fall of a Decadent City 1842-1949 (New York: HarperCollins, 2001):208.

- 1 2 John B. Powell, My Twenty Five Years in China (1945; Reprint: READ BOOKS, 2008):7.

- 1 2 Powell, 9.

- ↑ United States Court for China: Hearings, Sixty-first Congress, First Session on H.R. 4281. September 27, 28, October 1, 1917 (U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1917):34.

- ↑ Powell, 51.

- ↑ Hibbard, Bund, 216.

- ↑ Hibbard, Bund, 116.

- ↑ "Presentation to Captain H. E. Morton", North-China Herald (21 July 1917):36 (156).

- ↑ Ben Finney, Feet First (Crown, 1971):158.

- ↑ Yuan-tsung Chen, Return to the Middle Kingdom: One Family, Three Revolutionaries, and the Birth of Modern China (Union Square Press, 2008):73.

- ↑ Barbara Baker and Yvette Paris, Shanghai: Electric and Lurid City : an Anthology (Oxford University Press, 1998):100.

- ↑ Walter Hines Page and Arthur Wilson Page, eds. The World's Work 41 (Doubleday, Page & Co., 1921):454.

- ↑ Jeffrey W. Cody, "Building a China-Based Practice: Murphy amid Competitors in Shanghai and Beijing, 1918–1919" in Building in China: Henry K. Murphy's "adaptive architecture", 1914–1935 (Chinese University Press, 2001):89.

- ↑ Dong, 128-129; Stephen J. Valone, "A Policy Calculated to Benefit China" The United States and the China Arms Embargo, 1919–1929 (Greenwood Press, 1991).

- ↑ Fur-fish-game (1920):31-32.

- ↑ Lucian Swift Kirtland, Finding the Worth While in the Orient (R. M. McBride & company, 1926):175.

- ↑ Ron Gluckman, "Hipper than Hong Kong?" (November 2000)

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 18, 2006. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ↑ "Five-star legend", Shanghai Daily News (18 April 2005); (accessed 11 April 2009.

- ↑ "Shanghai to Merge Taxi Firms to Create New Leader" Reuters (3 June 2008)

- 1 2 "British Order Causes American Business Loss", The Evening Herald (Rock Hill, South Carolina) (May 6, 1920):6.

- ↑ China Monthly Review 12 (1920):235. Morton was in Manila in March 1923. See "Capt. Morton Talks on Shipping Board Activities", American Chamber of Commerce Journal (March 1923):9-14.

- ↑ Bardarson was of Danish heritage. He entered Canada on 7 October 1922 intending to reside there. See Library and Archives Canada, Form 30A Ocean Arrivals. Date of Arrival: 28 Oct 1922 Port of Arrival: Vancouver, British Columbia. Image 1121; Naturalization Record Type: Declarations of Intention Roll Description: (Roll 031) Declarations of Intention, 1921-1923, #15497-17496 Archive: National Archives, Washington, D.C. Collection Title: Naturalization Records for the Superior Court for King, Pierce, Thurston, and Snohomish Counties, Washington, 1850-1974 Archive Series: M1543 Archive Roll: 31; Title: Naturalization Records of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington, 1890-1957 Issue Date: 15 June 1923 State: Washington Locality, Court: Seattle, District Court Description: Petition and record, 1928, #14401-14708 > Image 2. Series: M1542. Another source indicates he was born 4 September 1877, and died 17 Oct 1944 in Alameda, California. See California Death Index. Social Security #: 554031031 Mother's Maiden Name: Eiricksson Father's Surname: Bardarson. Bardarson was married to Irene (born Butte, Montana).

- ↑ Naturalization Records of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington, 1890-1957 State: Washington Seattle, District Court Naturalization index, 1890-1937 Series: M1542, Image 288; John Willy, ed., Hotel Monthly 28 (1920):53; North-China Herald (11 June 1921):59; "Petition 973-R of W. Sharp-Bardarson (Seattle)", in United States. Dept. of the Treasury, Treasury Decisions Under Customs and Other Laws (U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1924):872.

- ↑ George Ephraim Sokolsky, China, a Sourcebook of Information (Pan-Pacific Association, Shanghai, 1920).

- ↑ Hibbard, Bund, 210.

- ↑ "Sudden Death of Mr. Edward Ezra", North-China Herald (17 December 1921):27 (767); "Internment [sic] of Mr. E.I. Ezra", North-China Herald (24 December 1921):25 (833).

- ↑ Hibbard, Bund, 121.

- 1 2 "Shanghai Hotels Sold", North-China Herald (13 May 1922):31; Hibbard, Bund, 211.

- ↑ It was founded in Hong Kong in March 1866. See "Topping Out Ceremony For The New Peninsula Shanghai" (17 April 2008)

- ↑ Hibbard, 4; and "Topping Out Ceremony For The New Peninsula Shanghai" (17 April 2008)