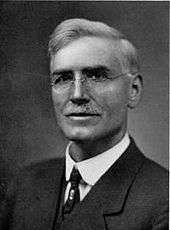

Hugh B. Lindsay

| Hugh Barton Lindsay | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Tennessee | |

|

In office 1889–1893 | |

| Preceded by | James C.J. Williams |

| Succeeded by | James H. Bible |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

November 3, 1856 Campbell County, Tennessee, United States |

| Died |

July 21, 1944 (aged 87) Knoxville, Tennessee |

| Resting place |

Old Gray Cemetery Knoxville, Tennessee[1] |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Elizabeth Foster |

| Profession | Attorney |

| Religion | Christian Church[2] |

Hugh Barton Lindsay (November 3, 1856 – July 21, 1944) was an American attorney, jurist and politician in Tennessee, who was appointed as United States Attorney for the Eastern District, serving from 1889 to 1893, and judge of Tennessee's Second Chancery District from 1894 to 1899. He was the Republican nominee for Governor of Tennessee in 1918, losing to Albert H. Roberts, as well as the Republican nominee for United States Senator in 1924, losing to Lawrence Tyson. As an attorney, Lindsay helped ALCOA become established as an industry in the region in the 1910s. He also helped launch the movement in the 1920s to create and preserve Great Smoky Mountains National Park.[2]

Early life and career

Lindsay was born near Coal Creek, Tennessee (now Lake City), one of five children of farmers Cornelius Lindsay and Valentine (Bowling) Lindsay.[3] He attended local schools before graduating from Franklin Academy in Jacksboro in 1880. He was admitted to the bar that same year, having read law with prominent Knoxville attorney Oliver Perry Temple. He moved to Huntsville, Tennessee, to practice law.[2]

In 1881, Lindsay was appointed to a commission to investigate moonshining in the Scott County area.[2] He was elected attorney general (district attorney) for the state's 16th Judicial District in 1884, and successfully ran for Scott County's seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1886, serving a single term.[2] Lindsay was an elector for Benjamin Harrison in the presidential election of 1888.[3]

In 1889, Lindsay was appointed U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Tennessee by President Harrison, and moved to the district's headquarters in Knoxville.[2] During his tenure, Lindsay prosecuted numerous moonshining cases, including 600 cases in 1891 alone. He also won successful convictions in a number of pension fraud cases, including that of Greeneville pension agent, W.R. Marshall, who was convicted of forging a Union Army pension.[4] Lindsay served as U.S. attorney until 1893, when Harrison's successor, Grover Cleveland, appointed James Bible to the position.

Following his term as U.S. Attorney, Lindsay was elected chancellor (judge) of Tennessee's Second Chancery District.[2] During his term, he ruled on a variety of cases, ranging from a dispute over the rights of academies to summarily fire teachers, to a case involving back taxes owed by the improvement company working to establish Harriman, Tennessee. One case, Guntert v. Guntert, involved an alcoholic who had deeded personal property to his sister for fear of squandering it, and then sued to get it back when she refused to return it.[5] Another, Citizens Railway Co. v. Africa, et al., was an effort to resolve the lengthy dispute between Knoxville's two streetcar companies, which had culminated in a riot known as the Battle of Depot Street in 1897.[6] Lindsay served as judge until 1899, when the state legislature abolished his district.[7]

Private practice and politics

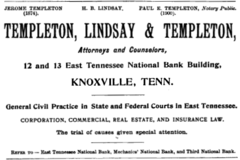

During the 20th century, Lindsay practiced as a senior partner in various law firms, including Templeton, Lindsay and Templeton; Lindsay, Young and Smith; Lindsay, Young, Smith and Donaldson; and Lindsay, Young and Atkins.[2] He worked as counsel for the Southern Appalachian Coal Operators Association, helping numerous regional coal companies incorporate. In the early 1900s, he helped Knoxville-based contractor William J. Oliver win a large settlement in a case against the federal government. Oliver had been the low bidder on the contract to build the Panama Canal in 1907, and sued when the administration of President Theodore Roosevelt rejected his bid, arguing he lacked the experience for the project.[2][8]

In 1910, the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) hired Lindsay to investigate the possibility of purchasing a string of hydroelectric dam sites on the Little Tennessee River to provide electricity for a massive aluminum smelting operation. Lindsay helped negotiate the purchase of the future sites for Santeetlah, Cheoah, and Calderwood dams.[2][9]

Lindsay defended accused murderer Gideon Rush Strong in a high-profile case in 1917. Strong had killed Samuel Luttrell, Jr., in a shootout in downtown Knoxville, believing he had raped his wife, Bonnie. He was eventually found guilty of voluntary manslaughter.[10]

During this period, Lindsay remained active in Republican Party politics. Though a Progressive, he threw his support behind incumbent Republican Governor Ben W. Hooper in his 1912 reelection campaign, denying critical support for a potential Progressive Party candidate who would have divided the party.[11] Lindsay was the Republican nominee for governor in 1918, though he did not stump, preferring a quiet campaign that focused on mail and personal contacts.[12] On election day, he was defeated by the Democratic nominee, Albert H. Roberts, 98,628 votes to 59,518.[13] Turnout was unusually low due to the absence of soldiers fighting in World War I and the raging influenza pandemic.[12]

The first meeting of the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association (GSMCA) took place in Lindsay's law office in December 1923, when Lindsay met with Willis Davis ("Father of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park"), Colonel David C. Chapman, and several others. He represented several major landholders within the proposed boundaries of the park.[2][14]

In 1924, Lindsay received the Republican nomination for United States Senator. While he ran a strong campaign,[2] he was defeated by popular World War I general, Lawrence Tyson, 147,825 votes to 109,863.[2][15]

Lindsay focused on his private law practice in his later years. He died on July 21, 1944, and was buried in Knoxville's Old Gray Cemetery.[2]

Family

Lindsay married Sarah Elizabeth Foster in 1883. They had eight children: Maude, Lillian, William, Charles, John, Robert, Hugh, Jr., and Katherine. Lindsay's paternal ancestors were Scottish, and his maternal ancestors, the Bowlings, were English.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Hugh B. Lindsay at Find a Grave

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Alice Howell, Lucile Deaderick (ed.), Heart of the Valley: A History of Knoxville, Tennessee (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1976), pp. 553-555.

- 1 2 3 Albert Osborne, Makers of America: Biographies of Leading Men of Thought and Action, Vol. 3 (Washington, D.C.: B.F. Johnson, 1917), pp. 354-362.

- ↑ Stephen Cresswell, Mormons and Cowboys, Moonshiners and Klansmen: Law Enforcement in the South and West, 1870–1893 (University of Alabama Press, 2002), p. 143.

- ↑ The Southwestern Reporter, Vol. 37 (1897), pp. 277, 396, 890.

- ↑ The Southwestern Reporter, Vol. 85 (1898), p. 485.

- ↑ John Wooldridge, George Mellen, William Rule (ed.), Standard History of Knoxville, Tennessee (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1900; reprinted by Kessinger Books, 2010), p. 475.

- ↑ Minutes of Meetings of the Isthmian Canal Commission, October 1905 to March 1907 (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1908), pp. 33-34.

- ↑ Russell Parker, "Alcoa, Tennessee: The Early Years, 1919–1939." East Tennessee Historical Society Publications, Vol. 48 (1976), p. 86.

- ↑ Donald Paine, "The Trial of Rush Strong," Tennessee Bar Association Journal, 27 April 2009. Retrieved: 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Phillip Langsdon, Tennessee: A Political History (Franklin, Tenn.: Hillsboro Press, 2000).

- 1 2 Paul Isaac, "Defeat and Victory: The Republican Party in Tennessee, 1918–1920," East Tennessee Historical Society Publications, Vol. 61 (1989), pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Our Campaigns - TN Governor, 1918. Retrieved: 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Carlos Campbell, Birth of a National Park In the Great Smoky Mountains (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1969), p. 16.

- ↑ Our Campaigns - U.S. Senator (Tennessee), 1924. Retrieved: 3 February 2013.