Hugh Fortescue, 2nd Earl Fortescue

| The Right Honourable The Earl Fortescue KG PC | |

|---|---|

|

"Hugh, Earl Fortescue KG, Lord Lieutenant of Devon". Wearing Garter Star. Marble bust by Edward Bowring Stephens, 1861; Memorial Hall, West Buckland School, Devon | |

| Lord Lieutenant of Ireland | |

|

In office 13 March 1839 – 11 September 1841 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Normanby |

| Succeeded by | The Earl de Grey |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 February 1783 |

| Died | 14 September 1861 (aged 78) |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse(s) |

(1) Lady Susan Ryder (1796–1827) (2) Elizabeth Geale (c. 1805–1896) |

| Alma mater | Brasenose College, Oxford |

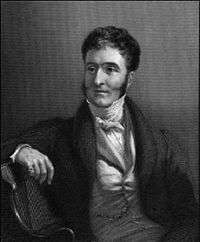

Hugh Fortescue, 2nd Earl Fortescue KG, PC (13 February 1783 – 14 September 1861), styled Viscount Ebrington from 1789 to 1841, was a British Whig politician. He served as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1839 to 1841.

Background and education

Fortescue was the eldest son of Hugh Fortescue, 1st Earl Fortescue, and Hester Grenville, daughter of Prime Minister George Grenville. He was educated at Eton and Brasenose College, Oxford.

Political career

Fortescue (as Ebrington) first became an MP for Barnstaple, just after his 21st birthday; and he sat for various constituencies almost continuously until 1839, when he was summoned to the House of Lords through a writ of acceleration in his father's junior title of Baron Fortescue.

Ebrington had entered Parliament in the 1800s as a Grenvillite connection, belonging to that section of the Whig party that supported the war with Napoleon; but in the following decade (in a generational shift) he broke away from them to join the Young Whigs.[2] Fearing the corruptive effects of militarism on British society,[3] the latter sympathised with the liberalising side of the French Revolution: Ebrington would later publish his conversations with Napoleon in his Elba exile.[4]

After the war, in 1817, Ebrington confirmed his breach with the bulk of his Grenville relatives,[5] and emerged as a prominent pro-Reform Whig - albeit one somewhat unusually rooted in a liberal, morally intense Anglicanism,[6] which he combined with an interest in political economy.[7] Ebrington strongly condemned the Six Acts as”the most alarming attack ever made by Parliament upon the liberties and constitution of the country”;[8] and during the 1820s, he would repeatedly promote and vote for Parliamentary Reform.[9]

When the Whigs finally came to power in 1830, Ebrington would come to play a significant part in the passing of the Great Reform Act. After the Commons passed the second bill, Ebrington convened a meeting of 100 reformist Whigs, urging strong measures should the Lords reject it, and acting as leader of a kind of pressure group on the Whig leadership: Ebrington himself appeared on a list of potential peer-creations drawn up to increase the pressure on the Lords.[10] When the Government finally resigned in the face of Tory intransigence in the House of Lords, Ebrington took the lead (in the face of leadership hesitations) in moving that the House of Commons implore the King “to call to his councils such persons only as will carry into effect unimpaired in all its essential provisions that Bill for reforming the Representation of the people which has recently passed this House ”.[11]

During the 1830s, Ebrington continued to lead a strong body of Reformist Whigs;[12] and he played a prominent role in establishing Whig party organisation under the new electoral system.[13] In 1839, as Baron Fortescue, he began serving under Lord Melbourne as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland;[14] and continued to do so until in 1841 he succeeded his father in the earldom. He went on to serve under Lord John Russell as Lord Steward from 1846 to 1850; was sworn of the Privy Council in 1839; and created a Knight of the Garter in 1856.

Portraits

A statue of the Earl stands in Exeter Castle Yard, and his marble bust is displayed on the staircase of the Memorial Hall in West Buckland School. 49 of the Fortescue family portraits were saved from the disastrous fire at Castle Hill of 9 March 1934 with minor smoke damage, but were shortly afterwards all destroyed by fire when the delivery lorry returning them from the restorer caught fire whilst parked overnight pending their return to Castle Hill.[15]

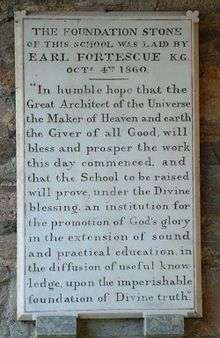

Co-founds West Buckland School

.jpg)

In 1858 together with Rev. J.L. Brereton, Prebendary of Exeter Cathedral and Rector of West Buckland, he founded the Devon County School, situated on land between West Buckland and East Buckland donated by him from his North Devon estate centred at Filleigh. The school was intended to provide a top quality education to local boys, including therefore the sons of many of his tenant farmers; it continues today as West Buckland School, an independent private school. A marble bust of Earl Fortescue, sculpted in 1861 by Edward Bowring Stephens (1815–82), stands on the staircase of the school's Memorial Hall.

Marriage & progeny

Lord Fortescue married twice:

- Firstly in 1817 to Lady Susan Ryder (d.1827), daughter of Dudley Ryder, 1st Earl of Harrowby. They had the following issue:

- Hugh Fortescue, 3rd Earl Fortescue (1818–1905)

- Hon. John Fortescue, MP

- Hon. Dudley Fortescue, MP

- Secondly in 1841, 14 years after the death of his first wife, to Elizabeth Geale (d. May 1896), daughter of Piers Geale and widow of Sir Marcus Somerville, 4th Baronet (c. 1775–1831).

Death & succession

Fortescue died in September 1861, aged 78, and was succeeded by his eldest son from his first marriage, Hugh Fortescue, 3rd Earl Fortescue.

Sources

- Leigh Rayment's Historical List of MPs

- Lauder, Rosemary, Devon Families, Tiverton, 2002, Fortescue, pp. 75–82

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl Fortescue

References

- ↑ Debrett's Peerage, 1968, p.461

- ↑ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad and Dangerous People? (Oxford 2006) p. 205

- ↑ E. A. Wasson, Whig Renaissance (Garland 1987) p. 64

- ↑ M. Zarzeizny, 'Mmeteors that Enlighten the Earth (2012) p. 147

- ↑ Fortescue, Hugh

- ↑ R. Brown, Church and State in Modern Britain (2002) p. 236

- ↑ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad and Dangerous People? (Oxford 2006) p. 205 and p. 521-3

- ↑ E. Wasson, A History of Modern Britain (2016) p. 141

- ↑ Fortescue, Hugh

- ↑ E. Pearce, Reform! (London 2003) p. 167 and p. 238

- ↑ Quoted in E. Pearce, Reform! (London 2003) p. 284

- ↑ Fortescue, Hugh

- ↑ P. Gray, Famine, Land and Politics (1999) p. 20

- ↑ E. Halevy, The Triumph of Reform (London 1961) p. 198

- ↑ Lauder, R. op.cit. p.81