Hugo Gellert

Hugo Gellert (May 3, 1892 – December 9, 1985) was a Hungarian-American illustrator and muralist. A committed radical, much of Gellert's work is agitational in nature and distinctive in style, considered by some art critics as among the best political work of the first half of the 20th century.

Biography

Early years

Hugo Gellert (Gellért Hugó in the Hungarian style)[1]was born Hugo Grünbaum on May 3, 1892 in Budapest, Hungary.[2] In 1906, the family emigrated to the United States, arriving in New York City, where they put down roots and changed their name.[2]

Gellert studied at the Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design.

His wife was named Livia.

Art and politics

Gellert, a committed socialist who later joined the Communist Party of America, considered his politics inseparable from his art. He had said that "Being an artist and being a communist are one and the same." He used his art to advance his ideals for the common people, and much of his art depicted what he saw as the injustices of racial divides and capitalism. Often his works were captioned with slogans that helped further the illustration. The Working Day, for example[3] shows a black laborer standing back to back with a white miner, and is accompanied by a phrase from Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, "Labor with a white skin cannot emancipate itself where labor with a black skin is branded.[4] "

Art as politics

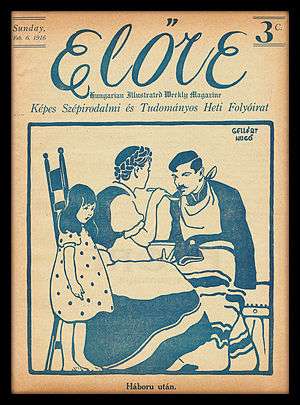

Opposed to World War I, Gellert published his first anti-war art in 1916. His work was prominently featured both in the illustrated magazine of the Hungarian Socialist Federation of the Socialist Party of America, Előre (Forward) as well as Max Eastman's radical monthly magazine The Masses from this time.[5] He also created numerous illustrations for Eastman's successor magazine, The Liberator, as well as sundry publications of the Communist Party USA after its formation, such as The Workers Monthly and The New Masses. Later, he was offered a position as a staff artist for The New Yorker magazine. In 1925, he moved to the New York Times.

In 1927, Gellert was appointed the leader of the Anti-Horthy League, the first American anti-fascist organization. In this capacity, he organized a demonstration against U.S. president Calvin Coolidge, and both he and his wife were arrested while picketing the White House.[6][7]

In 1932, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, feeling uncomfortable about Gellert’s public persona and politics, petitioned to have Gellert’s work removed from its collection. However, they were forced to reconsider when other artists, many of whom did not share Gellert’s social idealism, came to his defense as fellow artists and threatened to withdraw their own works.

In 1934 he was among the leaders of the Artists Committee of Action, an informal group which had formed to protest Nelson Rockefeller's destruction of Diego Rivera's mural Man at the Crossroads early in the year. Gellert was instrumental in the establishment of Art Front magazine, which started publication in November 1934 and was at first jointly published by the ACA and the Artists Union.[8]

In 1939, Gellert helped organize the group, “Artists for Defense” and he later became the Chairman for “Artists for Victory”, an organization that included over 10,000 members.

Death and legacy

Gellert died in Freehold Township, New Jersey on December 9, 1985.[2]

Gellert's social commentary, his work and his beliefs have placed him among the greatest American social artists of the Art Deco era according to experts in the field.[9]

His brother Ernest, also a socialist, was drafted in 1917 but refused induction, claiming to be a conscientious objector. Hugo fled to Mexico after Ernest died of a gunshot wound in prison at Fort Hancock, New Jersey, officially a suicide.[2] His brother Lawrence was a music collector who in the 1930s documented black protest traditions in the South of the United States.

Although remembered for his art in print, Gellert also painted a number of public murals and frescoes. Among the surviving frescoes is the series that adorn the front entryways of each of the four buildings of the Seward Park Housing Corporation, a housing cooperative with 1728 apartments, designed and built by Herman Jessor as part of the social housing cooperatives built by the Abraham Kazan and the United Housing Foundation,.[10] In 2003, the series became the topic of controversy after the cooperative converted from its limited equity status to a fully private and market-rate residential co-op. The cooperative attempted to remove or destroy the four giant Gellert murals. The Co-op board felt the socialist-style paintings were no longer representative of the people or the Lower East Side neighborhood.[11]

Public protests and letter writing, inspired threats of legal action and other possible setbacks, caused the plan to be delayed. Gellert’s artwork can still be seen in each of the buildings.[12]

Publications

- The Mirrors of Wall Street. Text by Anonymous, drawings by Gellert. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1933.

- Karl Marx' Capital in Lithographs. New York: R. Long and R.R. Smith, 1934.

- Comrade Gulliver: An Illustrated Account of Travel into that Strange Country the United States of America. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1935.

- “Aesop Said So”. New York: Covici Friede, 1936.

- Gellert, Lawrence (1936). Negro songs of protest. Illustrated by Hugo Gellert. New York, N.Y.: American music league. LCCN 36036401.

- Wallace, Henry Agard (1943). Century of the common man; two speeches by Henry A. Wallace. Illustrations by Hugo Gellert. New York: International Workers Order. LCCN 43012487.

See also

- Cooper Union

- Liberator, magazine

- New Masses

- The New Yorker

References

- ↑ See: his "Gellért Hugó" signature in his 1916 cover art from Elöre"

- 1 2 3 4 "Hugo Gellert : Biography". Spartacus Educational. Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ From Karl Marx in Pictures, published in 1993, France

- ↑ "Gellert Painting". Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ↑ The Masses collection at Michigan State University

- ↑ "THE PRESIDENCY: The Coolidge Week: Mar. 26, 1928". Time. March 26, 1928.

- ↑ "Gellert Life Time line". Graphicwitness.org. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ↑ Patricia Hills (2010). Art Front. Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed February 2015. (subscription required)

- ↑ "The Art of Print". The Art of Print. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ↑ "James Wechsler, CUNY Art History Department: Save Gellert's Seward Park Murals". Newdeal.feri.org. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ↑ Mount, Ian (September 21, 2003). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: LOWER EAST SIDE; New Masses, Old Murals". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ Lewine, Edward (May 17, 1998). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: LOWER EAST SIDE -- UPDATE; Seward Park Houses' 49-Year-Old Murals Get a Reprieve". The New York Times.

External links

- Overview of Hugo Gellert's life and work, GraphicWitness.org

- Hugo Gellert's Seward Park Murals. History and index page showing photographs of the four Seward Park murals. Retrieved October 1, 2009

- The Hugo Gellert Papers Online at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- Comrades in Art: Hugo Gellert