Human trafficking in New Zealand

Human trafficking is a crime in New Zealand under Section 98D of the Crimes Act 1961. In 2002, the New Zealand Government ratified the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (Palermo Protocol),[2] a protocol to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC). New Zealand participates in efforts to combat human trafficking in the Asia-Pacific region, and has a leadership role in the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Human Trafficking and related Transnational Crime (Bali Process).[3]:13

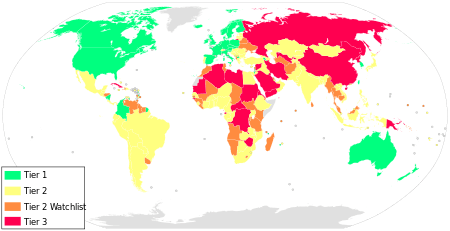

As human trafficking is not considered to be an active issue in New Zealand, the government focus is on prevention and identification of victims and offending.[3]:5 New Zealand has been classified as a destination country for human trafficking and a source location for domestic trafficking of forced labour, including children in the sex trade.[4] According to the United States Department of State annual reporting on the effectiveness of government actions to address human trafficking, New Zealand has consistently achieved a Tier One (highest) ranking, achieving full compliance with the minimum standards as contained in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act 2000 (TVPA).[5] These standards are generally consistent with the Palermo Protocol.[6]

To implement the Palermo Protocol, the Crimes Act 1961 was amended to include the offence of human trafficking in 2002.[7] In response to the Bali Process, New Zealand pledged to create a practical plan to address human trafficking and established the Inter Agency Working Group on People Trafficking (Working Group) in 2006.[3]:3 The Department of Labour, acting on behalf of the Working Group, released the Plan of Action to Prevent People Trafficking in 2009. The definition of human trafficking as involving exclusively transnational movement has meant that claims for domestic human trafficking in the workforce, sex industry and foreign fishing vessels have been pursued in other statutes, such as the Prostitution Reform Act 2003 (PRA) and the Immigration Act 2009 that attract lesser penalties. This issue is currently being addressed in a proposed legislative amendment.[8]

Governmental responses

Plans of action

The Inter Agency Working Group consists of the Department of Labour (now the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE)), Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Social Development, Ministry for Women, New Zealand Customs Service and the New Zealand Police. During the period of June to July in 2008, the Department of Labour held a public consultation to formulate a “whole of government approach”[3]:4 to human trafficking. 34 formal submissions were received which informed the development and subsequent publication of the Plan of Action to Prevent People Trafficking in 2009. The MBIE is responsible for ensuring that the plan is implemented and compiles an annual report on compliance.[3]:9 The plan of action contains three goals; Prevention, Protection and Prosecution. Under each of these, the plan identifies specific objectives and actions to be taken, and assigns a responsible agency and timetable for completion. The plan is considered to be a “living document”,[9] and following the pending legislative reform is due to be reassessed.[10]

Prevention of human trafficking

The New Zealand Government is committed to equip and train government officials and front-line officers to identify trafficking and respond appropriately through the establishment of mandatory education programmes.[4] This includes the promotion of public awareness in general.[3]:9 The MBIE is to conduct ongoing research in human trafficking and to assist in this, the National Intelligence Centre shares information legally with other governments.[3]:11

Given that human trafficking may involve transnational networks, domestic efforts are unlikely to achieve full protection, as “despite being a minor destination country, New Zealand remains disturbed by the dimension of people trafficking in the neighbouring Asia Pacific region."[11] New Zealand is a member of various International entities which address human trafficking, such as the Bali Process, the Pacific Immigration Directors’ Conference and the International Labour Organisation (ILO).[12] Financial assistance has been provided for human trafficking initiatives in the Asia Pacific region[13] through the New Zealand Agency for International Development.

Protection of human trafficking victims

Victims are certified with trafficked status by the New Zealand Police and the appropriate government agency conducts an investigation and may issue legal proceedings.[3]:16 If the victim is a temporary migrant, they may apply for an extension of visa for a 12-month period.[4] Following the investigation, migrant victims may apply for a resident visa and receive ongoing protection, provided that they have not obstructed the investigation.[14] The Health and Disability Eligibility Direction 2011 entitles all victims to receive government support, including legal aid, counselling and medical treatment, with full coverage under the Accident Compensation Scheme.[15] Victims may apply to Housing New Zealand and the Ministry of Social Development for assistance in the case of financial hardship.[3]:19 Given the low level of trafficking cases in New Zealand, there is no resource allocation dedicated to these services. Victims are assessed on a case-by-case basis and may be directed to receive additional support from Non-governmental organizations.[4]

Legislation

The offence of human trafficking

The Crimes Amendment Act 2002 added Sections 98C and 98D to the Crimes Act 1961 which prohibit the smuggling of unauthorized migrants for material benefit, and the trafficking of persons by coercion or deception. As a crime against humanity, the penalties are comparable to rape and murder, with a maximum of 20 years imprisonment or $500,000 fine, or both.[16] In accordance with the government’s “victim centred approach",[4] human trafficking may be established even if the victim acted voluntarily.[17] Several aggravating factors are provided to allow for appropriate sentencing.[18] All proceedings under these provisions require consent of the Attorney-General,[19] and a claim may be filed even if the victim(s) did not actually enter New Zealand.[20] The New Zealand Courts have extraterritorial jurisdiction over the crime of human trafficking and may prosecute New Zealand citizens who commit the offence on foreign territory.[21] To date, no convictions have been recorded and it has been suggested that the lack of prosecutions and investigations is due to the high evidentiary bar of the current law.[4] In August 2014, Immigration New Zealand charged three individuals with human trafficking, who have pleaded not guilty to arranging by deception the trafficking of 18 Indian nationals into forced labour in 2008-2009. The case has been referred to the High Court, and is pending trial in late 2015 to early 2016.[22] In 2014, the Organised Crime and Anti-corruption Legislation Bill was introduced to Parliament. Clause 5 changes the definition of human trafficking to include domestic movement, bringing New Zealand into conformity with the international definition, and adds exploitation as an element to the offence. The Bill is currently receiving submissions and a report is due in May 2015.[23]

Sex trafficking

In 2001 it emerged that migrant Thai women had been deceived into commercial sex arrangements in Auckland. No criminal prosecutions resulted, although one civil claim was successfully pursued.[24] The Human Rights Commission undertook the ‘Pink Sticker Campaign’ to raise awareness of exploitation and advertise a safe house for victims, and the Ministry of Justice suspended the visa free status between New Zealand and Thailand.[25] Labour inspectors visit legal brothels and the government regularly audits workplaces that employ migrants.[4] Since the legalisation of prostitution in 2003, The Prostitution Reform Act (PRA) makes it an offence to compel commercial sexual services.[26] To address the issue of illegal migrant sex workers, it is an offence to threaten to disclose unlawful immigrant status as a method of coercing a person to perform commercial sexual services.[27] It is also an offence to abduct a person for the purposes of marriage or sexual connection with the abductor or any other person without consent or with consent under fraud or duress.[28]

Sex trafficking of minors

The US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report 2014 identifies child prostitution as an issue, however there was no data available to support this claim.[4] Government officials have responded on numerous occasions that the reports are based on media releases as opposed to police evidence.[29] The PRA makes it an offence to facilitate or receive payment for commercial sex with a person under the age of 18,[30] with a maximum penalty of 7 years imprisonment.[31] Although persons aged 16 and over may legally have sex,[32] the increased age reflects New Zealand's obligation to comply with international obligations concerning children.[33] It is not an offence to provide commercial sexual services under the age of 18,[34] as the child is considered the victim. New Zealand ratified the Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography,[35] and made it unlawful to deal with a person under the age of 18 for the purposes of sexual exploitation, the removal of body parts or the engagement of forced labour.[36] In efforts to prohibit international sex tourism, The New Zealand Courts have jurisdiction over New Zealand citizens who engage in commercial sex on foreign territory with children under the age of 16.[37]

In cases concerning underaged victims, the courts have noted their concern for deterrence in sentencing.[38] In R v Raeleen Jo-Ann Prendeville[39] it was held that the defendant has the burden to show absence of fault of the knowledge of the victim’s age. In R v Allan Geoffrey Pahl[40] the fact that the defendant was misled to believe and pursue a fictional under-aged woman was irrelevant to the prosecution of the claim.

Forced labour

Slavery, including debt bondage and serfdom is crime in New Zealand.[41] Due to the extraterritorial definition of human trafficking, cases in the courts involving debt bondage and migrant labour have been prosecuted under Section 98 of the Crimes Act.[42] Migrants pose a particular issues to combating human trafficking. They may lack information or understanding of their rights due to language and cultural differences. If they are restricted to work with a particular employer, they might submit to threats if it is preferable to deportation, and they may fear shame if their family has supported their arrival to New Zealand or are relying on their earnings.[14] The Immigration Act 2009 allows for the prosecution of employers who exploit migrants or who commit serious breaches of employment laws such as the Holidays Act 2003, the Minimum Wage Act 1983 and the Wages Protection Act 1983.[43] In April 2015 the Immigration Act 2009 was amended to extend these protections to legal workers.[44] The government also targets the horticulture industry with its Regional Seasonal Employer (RSE) Policy which operates to maintain employment standards while responding to high labour demand.[45]

The demand for workers in the Canterbury region following the 2011 earthquakes has raised concerns of forced labour for migrant workers.[46] In 2013, the National Government pledged $7 million over four years towards this issue, allowing for the increased hiring of labour inspectors and immigration officers in the region.[47]

Foreign fishing vessels

In 1986, New Zealand adopted the fishing Quota Management System which allows Foreign Charter Vessels (FCV’s) to operate within New Zealand’s Exclusive Economic Zone(EEZ). Because these FCV’s were outside the jurisdiction of labour protections, employers have been able to exploit crew members and submit them to forced labour. New Zealand ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1996,[48] which prohibits the transport of slaves,[49] including within the EEZ.[50]

In 1997, the first proceedings alleging human rights abuses on a FCV were brought in the New Zealand courts and the crew members were awarded compensation.[51] The government conducted an investigation in 2004 and identified systemic human rights and contractual abuses but did not publicly release the findings.[52]:88 In September 2005, ten Indonesian crew of the Korean flagged Sky 75 vessel fled at port and complained to the New Zealand Police of subjection to inhumane conditions and non-payment of wages.[52]:82 In 2006, the government published the code of Practice on Foreign Fishing Crew.[53] As this was non-binding policy directive, there was no obligation for New Zealand authorities to enforce the code, therefore exploitation continued, with further successful claims in the courts raising awareness of the issue.[54] In 2010 the Oyang 70 sank, killing 6 crew members. Surviving crew members revealed that they had been subjected to human rights and contractual abuse.[55] In 2011, crew members of the Shin Ji and Oyang 75 alleged they had been subjected to physical, psychological and sexual abuse, suffered inhumane working conditions and punishments, and were underpaid or denied payment of wages, forced under threat to conceal this to authorities.[56] Following these allegations, the government conducted a Ministerial inquiry in March 2012.[57] A bill containing many of the recommendations in the report was introduced to Parliament but failed to pass. It was later reintroduced under urgency and the Fisheries (Foreign Charter Vessels and Other Matters) Amendment Act passed into New Zealand law in 2014. This amendment mandates that all FCV’s within the EEZ must reflag to New Zealand by 2016,[58] which will allow the New Zealand Courts full jurisdiction over all crew members, who will then be entitled to the same protections that are available to all workers in New Zealand. Additionally, an Observer Programme has been implemented in order to effectively monitor the situation.[59] The new legislation is hoped to bring an end to modern slavery in New Zealand's territorial waters.[60]

Judicial response

New Zealand holds judicial membership of the Advisory Council of Jurists in the Asia Pacific Forum.[61] Justice Susan Glazebrook has suggested that the judiciary must maintain an awareness of human trafficking as proceedings may be brought under different statutes, although the facts of the case may amount to the crime of human trafficking.[62]:12 The need for appropriate sentencing has been recognised, and the protection of victims, through the discretionary exercise of witness protection and consideration of the effects of their potential deportation.[62]:13

Non-governmental organisations

Various non-governmental organizations operate in New Zealand to provide assistance to research programs, offer victim response and promote general public awareness. Examples include the Human Rights Commission, Stop the Traffik Aotearoa, Oxfam New Zealand, Justice Acts New Zealand, Child Alert (ECPAT) NZ, and Slave Free Seas. The Salvation Army has co-sponsored ‘Prevent People Trafficking’ conferences in 2013 and 2014.

See also

Further reading

- Plan of Action to Prevent People Trafficking, Department of Labour, 2009

- Glazebrook, Susan (13 August 2010), Human trafficking and New Zealand (PDF), Auckland, N.Z.

- Global Trafficking in Persons Report 2014 (PDF), United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2014

- Protecting Our Innocence, Ministry of Justice, 2002

- Report of the Prostitution Law Review Committee on the Operation of the Prostitution Reform Act 2003, Ministry of Justice.

- Trafficking in Persons Report, U.S. Department of State, 2014

- Protecting the Vulnerable (PDF), New Zealand: Justice Acts New Zealand, 2014

- Temporary Migrants as Vulnerable Workers: A Literature Review (PDF), Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, 2014

References

- ↑ "Trafficking in Persons Report 2013". U.S. Department of State. 2013.

- ↑ Status of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children. treaties.un.org. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Plan of Action to Prevent People Trafficking" (PDF). dol.govt.nz. p. 13. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "New Zealand Country Report, Trafficking in Persons Report 2014" state.gov. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Pub L. 106-386.

- ↑ Definitions and Methodology, Trafficking in Persons Report 2014 state.gov. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Crimes Amendment Act 2002, Section 5.

- ↑ "Organised Crime and Anti-corruption Bill" parliament.govt.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ "Prevent People Trafficking Conference Report April 11-12 2013" salvationarmy.org.nz. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ "United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2014". unodc.org, p. 17. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Position paper to the General Assembly Third Committee, Delegation from New Zealand" madmun.de., p. 1. Retrieved 30 April 3015.

- ↑ New Zealand's International engagement. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ .

- 1 2 'Working Together to Combat People Trafficking and Migrant Exploitation', available on . immigration.govt.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ "2012 United Nations Convention against Torture, New Zealand Draft Periodic Review 6" justice.govt.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Sections 98C(3),98D(2).

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 98D(4).

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 98E(1) and (2).

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 98F(1).

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 98D(3)(a)-(b).

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 7A.

- ↑ Weekes, John. 2014. "NZ's first human trafficking trial". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ . Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ "People Trafficking: an International Crisis Fought at the Local Level" (PDF). Fulbright New Zealand. 2006. p. 88. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Human Trafficking and Organizations. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Prostitution Reform Act, Section 16.

- ↑ PRA, Section 16(c)(iii).

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 208.

- ↑ Gulliver ,Aimee.2014. "NZ brushes off human trafficking report". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2015; NZPA, 2006. “NZ rebuffs child trafficking, prostitution claims in US report”. nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ PRA, Sections 20-22.

- ↑ PRA,Section 23.

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 134.

- ↑ United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 34 and 35; International Labour Organization Convention 162 Concerning the Worst Forms of Child Labour, Article 1.

- ↑ Prostitution Reform Act, Section 23(3).

- ↑ "Status of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography". treaties.un.org. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 98AA.

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 144A.

- ↑ Police v Antolik [2004] DC 631 (Christchurch), para. 52; R v Gillanders DC (Christchurch) T0313661/05, at [16].

- ↑ DC (Wellington) 085-575/05.

- ↑ DC (Dunedin) T03/13150/04.

- ↑ Crimes Act 1961, Section 98.

- ↑ R v Rahimi CA4/02 (30 April 2002); Elliot v Kirk AT17/01 (19 February 2001), R v Chechelnitski CA160/04 (1 September 2004).

- ↑ Immigration Act 2009, Section 351.

- ↑ Immigration Amendment Bill (No 2); New Zealand Government Press Release. 2014. "Migrant exploitation bill passed". scoop.co.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Regional Seasonal Employer Policy. dol.govt.nz. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Morrah, Michael.2014.“Christchurch rebuild migrants face debts, cramped accommodation”. 3news.co.nz. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Hon. Michael Woodhouse. 2014. Introduction To Prevent People Trafficking Conference 2014 national.org.nz. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Status of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 2010". Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Article 99.

- ↑ United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Article 58(2).

- ↑ Udovenko v Karelybflot HC (Christchurch) AD90/98 (24 May 1999); Karelrebflot v Udovenko [2000] 2 NZLR 24 (CA) (17 December 1999).

- 1 2 Devlin, Jennifer. 2009. “Modern Day Slavery: Employment Conditions for Foreign Fishing Crews in New Zealand Waters”. austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ "Code of Practice on Foreign Fishing Vessels". immigration.govt.nz Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ D V Ryboproduckt Limited v The 49 crew of the MFV Aleksandr Ksenofonotov [2007] Employment Relations Authority, CA10/07, 5072931 (Unreported, James Crichton, 30 January 2007).

- ↑ Stringer, Christina., Simmons, Glenn and Coulston,Daren (2014). "Not in New Zealand's waters, surely? Labour and human rights abuses aboard foreign fishing vessels" (PDF). dol.govt.nz. p. 3. Retrieved 30 April 2015..

- ↑ Simmons, Glenn and Stringer, Christina, 2014. "NZ Fisheries Management System: Forced labour an ignored or overlooked dimension?" Marine Policy 50, 74-80, at P. 79.

- ↑ . fish.govt.nz Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Fisheries Act 1996, Section 103.

- ↑ Fisheries Act 1996, Section 233.

- ↑ ONE news.2014. “Fishing Slavery Bill Passes final Hurdle”. tvnz.co.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- 1 2 Glazebrook, Susan. "Human Trafficking and New Zealand" (PDF). courtsofnz.govt.nz. Retrieved 30 April 2015..

External links

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- The Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime

- U.S. Department of State Trafficking in Persons Reports

- Migrant Protection in New Zealand

- Migrant Exploitation Information

- Migrant Settlement in New Zealand

- Practical Guidance for Lawyers on Slavery

- New Zealand at HumanTrafficking.org

- New Zealand Human Rights Commission

- Child Alert ECPAT NZ

- Stop the Traffik Aotearoa

- Slave Free Seas

- Collection of Resources and Media Articles on Foreign Shipping Vessels