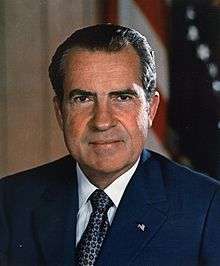

Impeachment process of Richard Nixon

In 1974, Richard Nixon, the 37th President of the United States, was in the process of being impeached by the United States House of Representatives on several charges related to the Watergate scandal. The House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment against him and reported those articles to the House of Representatives. The impeachment resolutions were never considered by the full House, as Nixon resigned from the presidency on August 9, 1974 before the House acted. It is widely believed that had Nixon not resigned, his impeachment by the House and removal from office by a trial of the United States Senate would have occurred.

Although it did not go as far as the impeachments of Andrew Johnson in 1868 and of Bill Clinton in 1998, this was otherwise the furthest any impeachment effort against a United States president has reached. It was the most successful in its effect, since it directly led to the departure from office of its target, while the two actual trials resulted in acquittals.

Pre-Watergate impeachment efforts

On May 9, 1972, Representative William Fitts Ryan submitted a resolution, H.Res. 975, to impeach President Nixon. The resolution was referred to the Judiciary Committee.[1] The next day, John Conyers introduced a similar resolution, H.Res. 976.[2] On May 18, 1972, Conyers introduced his second resolution, H.Res. 989, calling for President Nixon's impeachment. The resolutions were referred to the Judiciary Committee, where they died. These actions occurred before the break-in at the Watergate complex.

Representative Robert Drinan of Massachusetts on July 1973, called to introduce a resolution calling for the impeachment of Nixon, though not for the Watergate scandal. Drinan believed that Nixon's secret bombing of Cambodia was illegal, and as such, constituted a "high crime and misdemeanor". However, the Judiciary Committee voted 21 to 12 against including that charge among the articles of impeachment that were eventually approved and reported out to the full House of Representatives.

Early Watergate impeachment efforts

|

Congressman Jerome Waldie | |

|

|

The Watergate scandal began with the June 17, 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C., and the Nixon administration's attempted cover-up of its involvement. When the conspiracy was discovered and investigated by the United States Congress, the Nixon administration's resistance to its probes led to a constitutional crisis.[4]

The scandal grew to involve a slew of additional allegations against the President, ranging from the improper use of government agencies to accepting gifts in office and his personal finances and taxes; Nixon repeatedly stated his willingness to pay any outstanding taxes due, and paid $465,000 in back taxes in 1974.[5]

As the Watergate affair heated up in the summer of 1973, Representative Drinan tried again, introducing H

By September 1973, there was a sense that Nixon had regained some political strength, the American public had become burned out by the Senate hearings, and that Congress was not willing to undertake impeachment, absent some major revelation from the White House tapes or some major new action by Nixon against the investigation.[7]

There was sufficient interest in impeachment possibilities during these months, however, that the House Judiciary Committee put together a 718-page historical collection of often hard-to-find Congressional and previously published scholarly material on impeachment. Published on October 9, 1973, the Foreword stated, "In recent months, the Committee on the Judiciary has daily received numerous requests for information regarding the constitutional and procedural bases for the impeachment of [officials]...."[8]

As the Watergate saga unfolded, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) became the first national organization to call for Nixon's impeachment.[9] Civil rights attorney Charles Morgan, Jr. was involved in the ACLU's effort to have President Nixon impeached from office; in fact, he led the effort.[10] This, following a resolution opposing the Vietnam War, was controversial as it was the second major decision that caused critics of the ACLU, particularly conservatives, to claim that the ACLU had evolved into a liberal political organization.[11]

After Nixon fired Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox in what has been called the "Saturday Night Massacre" of October 20, 1973, however, momentum towards impeachment grew rapidly. (In the view of Nixon speechwriter Pat Buchanan, who had been privy to Nixon's thinking, the president had known this would be the likely outcome of dismissing Cox.[12]) On October 23, 1973, a landslide of resolutions calling for impeachment, impeachment investigations, and appointment of a special prosecutor were introduced against Nixon.[13] The introduction of these resolutions continued for several days, but the Judiciary Committee was reluctant to start a formal investigation, especially with the Vice Presidency vacant after the resignation amid scandal of Spiro Agnew on October 10, 1973.

Overall, as the Watergate scandal developed during 1973, Carl Albert, as Speaker of the House, referred some two dozen impeachment resolutions to the House Judiciary Committee for debate and study.[14]

The House Judiciary Committee takes up the case

Congressional Democrats found themselves under much pressure to hold hearings on Nixon's alleged abuse of presidential powers. Representative Peter W. Rodino of New Jersey, a Democrat, had only been Judiciary Chairman for a few months when his committee began to hear the case for Nixon's impeachment. Until the Watergate scandal, Rodino had spent his political career largely below the radar screen. Watergate put Rodino front and center in the political limelight. "If fate had been looking for one of the powerhouses of Congress, it wouldn't have picked me," Rodino told a reporter at the time.[15]

After the Saturday Night Massacre, Rodino began his committee's investigation. On October 30, 1973, the House Judiciary Committee began consideration of the possible impeachment of Richard Nixon. The initial straight party-line votes by a 21–17 margin were focused around how extensive the subpoena powers Rodino would have would be.[16]

By early January 1974 there was sufficient chance of impeachment moving forward that Nixon wrote in his diary that his main approach to defending against such a move would be to "act like a president" with respect to foreign and domestic duties.[17] At the end of his January 30 State of the Union address, Nixon asked for an expeditious resolution to any impeachment proceedings against him, so that the government could function fully effectively again.[18]

The Judiciary Committee set up a staff, the Impeachment Inquiry staff, to handle looking into the charges, that was separate from its regular Permanent staff.[19] Based upon the recommendations of many in the legal community, John Doar, a well-known civil rights attorney in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations who was a long-time Republican turned Independent, was hired by Rodino in December 1973 to be the lead special counsel for the Impeachment Inquiry staff.[20] Albert E. Jenner, Jr. was named in January 1974 as top counsel on the Impeachment Inquiry staff for the Republican minority on the committee.[21]

The four Senior Associate Special Counsels to the Impeachment Inquiry staff were Joseph A. Woods, Jr., Richard Cates, Bernard W. Nussbaum, and Robert D. Sack[22] (who originally served as Associate Special Counsel).

Much research needed to be done, as there had not been an actual impeachment in the House since that of Judge Halsted L. Ritter in 1936.[23] House Librarian Emanuel Raymond Lewis provided critical historical references to guide the committee in its work.[24]

With pressure growing and a new Vice President, Gerald Ford, in place since December 6, 1973, the House passed a resolution, H

In March 1974, the D.C. grand jury that had been involved in the case since the original 1972 indictments against the Watergate burglars, handed up its most significant indictments in the case, including Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell, and others. Because prosecutors informed the grand jury that the Constitution likely prohibited the indictment of an incumbent president, with impeachment thus the only recourse, the jurors recommended that materials making a criminal case against President Nixon be turned over to the House Judiciary Committee.[28]

Talk of possible impeachment included considerations of how it might affect U.S. foreign relations. During the spring of 1974, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger publicly proclaimed his expectation that the president would neither be impeached nor resign, but privately he worried that the country's ability to deal with foreign problems would be significantly damaged by an impeachment.[29] Kissinger later said this fear manifested itself during Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II) negotiations in April 1974, when Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko asked him how the U.S. government would function if impeachment came to pass. Kissinger assessed that the Politburo was unlikely to extend concessions given the uncertainty.[30]

The Impeachment Inquiry staff hired 34 counsels reporting to Doar or the other senior lawyers on the staff.[22] One who later became well-known was William Weld.[22] Another was Hillary Rodham.[31] Under the guidance of Doar and Nussbaum,[32] Rodham helped research procedures of impeachment and the historical grounds and standards for impeachment.[31] As part of this she wrote a brief supporting Rodino's belief that during the initial evidentiary hearings to determine whether potential grounds for impeachment exist, the target of the possible impeachment has no right to representation by counsel during the hearings.[19] Altogether there were 44 lawyers on the staff, of whom only 3 were women, and close to a 100 total people when researchers, clerks, typists, and other support personnel were enumerated.[33]

Like other committee staffers, Rodham worked long, sometimes tedious hours.[33] She and some of the other women on the staff had to post a sign telling the male staffers that they were not there to make coffee for them.[34]

(The lead counsel for the regular, non-impeachment staff of the Judiciary Committee, Jerry Zeifman, decades later made charges without evidence that the committee had intentionally dragged out the impeachment process, hoping to keep a politically wounded Nixon in office for his full second term and thus facilitate the election of Ted Kennedy to the presidency. Zeifman also claimed that Rodham had behaved unethically on the committee and that he had fired her; both claims have been thoroughly debunked.[19][22])

The committee spent eight months gathering evidence and pushed Nixon to comply with a subpoena for conversations taped in the Oval Office.[35] Its quarters were in the old Congressional Hotel,[33] which had become the O'Neill House Office Building. The case was put together on more than 500,000 five-by-seven-inch notecards that were cross-indexed against each other.[36] A constant worry among committee leaders was that leaks from their research, deliberations, and preliminary conclusions would leak to the press; Doar in particular had the junior lawyers on the inquiry working on isolated areas so that only a few of the senior counsels knew the big picture.[23] Opinions differ as to how successful they were at preventing leaks, with some saying they were[36][37] and some saying they were not.[35]

In the view of Doar, Chairman Rodino "insisted that [the inquiry's work] be bipartisan, it not be partisan. There was no partisanship on the staff. In fact, it was remarkably non-partisan. And that is the result of good leadership. And although Congressman Rodino was a quiet man, he had the knack of leading, of managing, and he did it very well, in my opinion."[37]

Impeachment hearings

The House Judiciary Committee opened impeachment hearings against the President on May 9, 1974, which were televised on the major U.S. networks.

The hearings lasted until the summer when, after much wrangling, the Judiciary Committee voted three articles of impeachment to the floor of the House, the furthest an impeachment proceeding had progressed in over a century.

Focus was on Article One of the United States Constitution.

At the time of the initial impeachment investigations, it was not known if Nixon had known and approved of the payments to the Watergate defendants earlier than this conversation. Nixon's conversation with Haldeman on August 1, 1972, is one of several that establishes this. Nixon states: "Well…they have to be paid. That's all there is to that. They have to be paid."[38] During the congressional debate on impeachment, some believed that impeachment required a criminally indictable offense. President Nixon's agreement to make the blackmail payments was regarded as an affirmative act to obstruct justice.[39]

Focus was also on allegations of misuse in a discriminatory manner of the Internal Revenue Service and other federal agencies.[40]

Democrat Ray Thornton of Arkansas was part of a group of three southern Democrats and four moderate Republicans who drafted the articles adopted by the Committee. Representative William L. Hungate of Missouri was chosen to propose the second of the three articles of impeachment. Democrat Jack Brooks of Texas was the one who drafted the articles of impeachment adopted by the Committee. For this reason, Nixon later called Brooks his "executioner."[41]

Democratic member Barbara Jordan of Texas made an influential televised speech before the House Judiciary Committee supporting the process of impeachment of Nixon.[42] Known as the Statement on the Articles of Impeachment, delivered on July 25, 1974, Jordan delivered a fifteen-minute opening speech[43] This speech is thought to be one of the best speeches of the 20th century.[44] Throughout her speech, Jordan strongly stood by the Constitution of the United States of America. She defended the checks and balances system, which was set in place to inhibit any politician from abusing their power. Jordan never flat out said that she wanted Nixon impeached, but rather subtly and cleverly implied her thoughts.[45] She simply stated facts that proved Nixon to be untrustworthy and heavily involved in illegal situations.[45] She protested that the Watergate scandal will forever ruin the trust American citizens have for their government.[45] This powerful and influential statement earned Barbara Jordan national praise for her rhetoric, morals, and wisdom.[42]

Democratic Representative Walter Flowers of Alabama, a conservative Democrat, was considered to be leaning against the impeachment vote. After a long struggle which caused an ulcer to recur, Flowers indicated he would vote for impeachment. The congressman said "I felt that if we didn't impeach, we'd just ingrain and stamp in our highest office a standard of conduct that's just unacceptable."[46] Coming from a state which had supported Nixon in 1972, he was seen as influential even with some Republicans. He told the undecided Republicans on the committee, "This is something we just cannot walk away from. It happened, and now we've got to deal with it.[46]

Representative Elizabeth Holtzman of New York, a young Democrat, also drew national media attention as a member of the committee.[47] As a member of the Judiciary Committee, Drinan also played an integral role in the Congressional investigation of Nixon Administration misdeeds and crimes.

Republican Charles E. Wiggins of California was Nixon's fiercest and ablest defender on the committee.[48] Republican Charles W. Sandman, Jr. of New Jersey defended Nixon almost throughout the proceedings. At one point during the hearings, Sandman angrily told his New Jersey colleague on the committee, Chairman Rodino, "Please, let us not bore the American public ... you have your 27 votes", referring to the 27 affirmative votes for the first article of impeachment against Nixon.

Attorney James D. St. Clair represented Nixon before the House Judiciary Committee as they considered the impeachment charges against him.

Sam Garrison was a lawyer who also defended Nixon during impeachment process.[49]

Law professor Raoul Berger was a popular academic critic of the doctrine of "executive privilege" and was viewed as playing a significant role in undermining Nixon's constitutional arguments during the impeachment process.[50]

These hearings culminated in votes for impeachment.[51] As the Judiciary Committee prepared for the vote, Rodino said: "We have deliberated. We have been patient. We have been fair. Now the American people, the House of Representatives and the Constitution and the whole history of our republic demand that we make up our minds."[15]

Articles of impeachment

The committee, with six Republicans joining the Democratic majority, passed three of the five proposed articles of impeachment.[15]

On July 27, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee voted 27–11 to recommend the first article of impeachment against the president: obstruction of justice.[51] The House then recommended the second article, abuse of power, on July 29, 1974. The next day, on July 30, 1974, the House recommended the third article: contempt of Congress.

Part of Article 2 of the Bill of Impeachment against President Nixon read:

- Resolved, That Richard M. Nixon, President of the United States, is impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors ...

- Using the powers of the office of President of the United States, Richard M. Nixon, in violation of his constitutional oath faithfully to execute the office of President of the United States ...

- He has, acting personally and through his subordinates and agents, endeavored to ... cause, in violation of the constitutional rights of citizens, income tax audits or other income tax investigations to be initiated or conducted in a discriminatory manner.[40]

In a 1989 interview with Susan Stamberg of National Public Radio, Rodino recalled that after the vote he went to a room in back of the committee chambers, called his wife and cried. "Notwithstanding the fact that I was Democrat, notwithstanding the fact that there were many who thought that Rodino wanted to bring down a president as a Democrat, you know, he was our president. And this is our system that was being tested. And here was a man who had achieved the highest office that anyone could gift him with, you know. And you're bringing down the presidency of the United States, and it was a sad, sad commentary on our whole history and, of course, on Richard Nixon."[37]

The Committee voted 21–12 against including the administration's falsification of records concerning the secret bombing of Cambodia in the articles of impeachment leveled against President Nixon.[52]

Another article of impeachment was also not passed.[15]

Dénouement

Even with support diminished by the continuing series of revelations, Nixon hoped to fight the impeachment charges. He was closely studying the possible vote counts that impeachment in the House or trial in the Senate would get; Kissinger later sympathetically described the president at this time as "a man awake in his own nightmare."[53]

According to Senator Jacob Javits, a Senate trial was not likely to start before November 1974 and might run to late January 1975 before there was a verdict.[54] Because Nixon might be forced to be in attendance during the Senate proceeding, Kissinger came up with plans to form a small group to manage the government in the president's place, to be composed of a few top Cabinet officers and Congressional leaders as well as White House Chief of Staff Al Haig.[54]

But on July 24, the Supreme Court had ruled unanimously in United States v. Nixon that the full Nixon White House tapes, not just selected transcripts, must be released.[55]

As a consequence, on August 5, 1974, the White House released a previously unknown audio tape from June 23, 1972. Recorded only a few days after the break-in, it documented the initial stages of the coverup: it revealed Nixon and aide H. R. Haldeman meeting in the Oval Office and formulating a plan to block investigations by having the CIA falsely claim to the FBI that national security was involved. This demonstrated that Nixon had been told of the White House connection to the Watergate burglaries soon after they took place, and had approved plans to thwart the investigation. In a statement accompanying the release of what became known as the "Smoking Gun Tape", Nixon accepted blame for misleading the country about when he had been told of White House involvement, stating that he had a lapse of memory.[56]

The release of the "smoking gun" tape destroyed Nixon politically. The ten representatives who voted against all three articles of impeachment in the House Judiciary Committee announced they would all support impeachment when the vote was taken in the full House.

Representative Wiggins in particular dropped his support for Nixon after the revelation of this tape.[48] Wiggins said, however, he would still oppose some of the passed articles that were not affected by the new revelation. Sandman announced that he too would vote for impeachment on the House floor after the release of the transcript, as did all of the Republicans who had voted against the articles in committee.

On the night of August 7, 1974, Senators Barry Goldwater and Hugh Scott and Representative John Rhodes met with Nixon in the Oval Office and told him that his support in Congress had all but disappeared. Rhodes told Nixon that he would face certain impeachment when the articles came up for vote in the full House. Goldwater and Scott told the president that there were not only enough votes in the Senate to convict him, but that no more than 15 Senators were willing to vote for acquittal – far fewer than the 34 he needed to avoid removal from office.[57]

And so with impeachment and removal by the Senate all but certain, on August 9, 1974, Nixon became the first president to resign.[58]

Aftermath

With President Nixon's resignation, Congress dropped its impeachment proceedings. On August 20, 1974, the House authorized the printing of the Committee report H. Rept. 93-1305, which included the text of the resolution impeaching President Nixon and set forth articles of impeachment against him.[59][60]

Criminal prosecution was still a possibility both on the federal and state level.[61] Nixon was succeeded by Vice President Gerald Ford as President, who on September 8, 1974, issued a full and unconditional pardon of Nixon, immunizing him from prosecution for any crimes he had "committed or may have committed or taken part in" as president.[62]

Nixon proclaimed his innocence until his death in 1994. In his official response to the pardon, he said that he "...was wrong in not acting more decisively and more forthrightly in dealing with Watergate, particularly when it reached the stage of judicial proceedings and grew from a political scandal into a national tragedy."[63]

The legacy of several of the House Judiciary Committee members was affected by the impeachment process.

Rodino's forty-year career in the House would become mostly remembered, in a positive light, for his role during the impeachment hearings.[64] Jordan's eloquence on the committee enhanced her national reputation and in 1975, she was appointed by Albert to the Democratic Steering and Policy Committee. Jordan was mentioned as a possible running mate to presidential nominee Jimmy Carter.[65] She instead delivered the keynote address at the 1976 Democratic National Convention, the first African-American woman to do so.[65]

Wiggins's advocacy for Nixon almost cost him reelection in 1974.[66] He was re-elected one more time before retiring from Congress. Sandman's reputation was severely tarnished by his performance in the televised hearings. He was soundly defeated by Democrat William J. Hughes, his opponent in 1974.

See also

- 93rd United States Congress

- Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- Impeachment of Bill Clinton

- List of federal political scandals in the United States

- Pardon of Richard Nixon

References

- ↑ 1972 Congressional Record, Vol. 118, Page H16350

- ↑ 1972 Congressional Record, Vol. 118, Page H16663

- ↑ "Advocates; Should The President Be Impeached?". Open Vault at WGBH. January 3, 1974. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ↑ "A burglary turns into a constitutional crisis". CNN. June 16, 2004. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ↑ Samson, William (2005). "President Nixon's Troublesome Tax Returns". TaxAnalysts. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ 1973 Congressional Record, Vol. 119, Page H27062

- ↑ R. W. Apple, Jr. (1973). "'There Was a Cancer Growing on the Presidency ...'". In Staff of the New York Times. The Watergate Hearings: Break-in and Cover-up. Bantam Books. pp. 61–65.

- ↑ Impeachment: Selected Materials. Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, 93rd Congress, First Session, U.S. Government Printing Office. October 1973. p. iii.

- ↑ Walker, Samuel (1990), In Defense of American Liberties: A History of the ACLU, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-504539-4, pp. 292–294. The ACLU published a full page newspaper advertisement on October 14, 1973, urging impeachment.

- ↑ Reed, Roy. "Charles Morgan Jr., 78, Dies; Leading Civil Rights Lawyer." The New York Times. The New York Times, 9 Jan. 2009. Web. 3 Nov. 2013.

- ↑ Walker, p. 294

- ↑ Woodward, Bob; Bernstein, Carl (1976). The Final Days (paperback). New York: Avon Books. p. 60.

- ↑ 1973 Congressional Record, Vol. 119, Page H34871 -73

- ↑ Little Giant, by Carl Albert, with Danney Goble, Norman, Oklahoma, University of Oklahoma Press, 1990.

- 1 2 3 4 Shipkowski, Bruce (8 May 2005). "Peter Rodino Jr., 96; led hearing on Nixon impeachment". Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Naughton, James M. (October 31, 1973). "House Panel Starts Inquiry On Impeachment Question". The New York Times. pp. 1, 30.

- ↑ Henry Kissinger (1982). Years of Upheaval. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 804–805.

- ↑ Kissinger, Years of Upheaval, p. 914.

- 1 2 3 Mikkelson, David (October 21, 2014). "Zeif-geist". Snopes.com. Updated July 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Man in the News: A Hard‐Working Legal Adviser: John Michael Doar". The New York Times. December 21, 1973. p. 20.

- ↑ Farrel, William E. (January 25, 1974). "Man in the News: G.O.P. Aide in Inquiry". The New York Times. p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 Kessler, Glenn (September 6, 2016). "The zombie claim that Hillary Clinton was fired during the Watergate inquiry". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 Bernstein, A Woman in Charge, p. 95.

- ↑ "Notable deaths in the Washington area: Emanuel Raymond Lewis, U.S. House librarian". The Washington Post. June 20, 2014.

- ↑ 1974 Congressional Record, Vol. 120, Page H2349 -50

- ↑ 1974 Congressional Record, Vol. 120, Page H2362 -63

- ↑ Naughton, James M. (February 7, 1974). "House, 410–4, Gives Supboena Power in Nixon Inquiry". The New York Times. pp. 1, 22.

- ↑ Carl Bernstein; Bob Woodward (1974). All the President's Men. New York: Warner Paperback Library. pp. 366–367.

- ↑ Marvin Kalb; Bernard Kalb (1974). Kissinger. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 547.

- ↑ Kissinger, Years of Upheaval, pp. 1025–1026.

- 1 2 Bernstein, Carl (2007). A Woman in Charge: The Life of Hillary Rodham Clinton. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40766-9., pp. 94–96, 101–103.

- ↑ Bernstein, A Woman in Charge, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 Bernstein, A Woman in Charge, p. 96.

- ↑ Bernstein, A Woman in Charge, pp. 98–99.

- 1 2 Wood, Anthony R.; Horvitz, Paul (8 May 2005). "Ex-congressman Peter Rodino, 95, dies The N.J. Democrat headed impeachment hearings that led Nixon to resign.". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- 1 2 Bernstein, A Woman in Charge, pp. 101–102.

- 1 2 3 All Things Considered (8 May 2005). "Watergate Figure Peter Rodino Dies". National Public Radio (NPR).

- ↑ Kutler, S: Abuse of Power, page 111. Simon & Schuster, 1997. Transcribed conversation between President Nixon and Haldeman.

- ↑ Bernstein, C. and Woodward, B: The Final Days, page 252. Simon & Schuster, 1976.

- 1 2 "Impeachment Proceedings Against President Nixon". United States Government Publishing Office. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ↑ Cahn, Emily (December 5, 2012). "Jack Brooks of Texas Dies at 89". CQ Roll Call.

- 1 2 "Barbara C. Jordan". History.com. 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ "Barbara C. Jordan Profile," The History Channel, A&E Television Networks, LLC. 1996-2013. http://www.history.com/topics/barbara-c-jordan.[] Accessed 5 October 2013

- ↑ "American Rhetoric: Top 100 Speeches," American Rhetoric Website, 2001-2013. http://www.americanrhetoric.com/top100speechesall.html.[] Accessed 5 October 2013

- 1 2 3 "Mr.Newman's Digital Rhetorical Symposium: Barbara Jordan: Statement on the Articles of Impeachment, "Newman Rhetoric Blogging Website, 2010. http://www.newmanrhetoric.blogspot.com. Accessed 5 October 2013.

- 1 2 "The Fatal Vote to Impeach". Time.com. 1974-08-05. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ↑ Holtzman, Elizabeth. "Elizabeth Holtzman". Huffington Post.

- 1 2 Pace, Eric (March 8, 2000). "Charles Wiggins, 72, Dies; Led Nixon's Defense in Hearings". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ↑ Mike Allen; Amanda Codispoti (31 May 2007). "Lawyer relished role as activist: Gay rights topped the list of Sam Garrison's causes during a career with its share of ups and downs". Roanoke Times.

- ↑ Crapanzano, Vincent (2000). Serving the Word: Literalism in America from the Pulpit to the Bench. New York: The New Press. pp. 246–251. ISBN 1-56584-673-7.

- 1 2 The Washington Post, Nixon Resigns.

- ↑ War in the Shadows, p. 149.

- ↑ Kissinger, Years of Upheaval, p. 1181.

- 1 2 Kissinger, Years of Upheaval, pp. 1193–1194.

- ↑ Ambrose, Stephen E. (1991). Nixon: Ruin and Recovery 1973–1990. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 394–395. ISBN 978-0-671-69188-2..

- ↑ Ambrose, Nixon, pp. 414–416.

- ↑ Black, Conrad (2007). Richard M. Nixon: A Life in Full. New York: PublicAffairs Books. p. 978. ISBN 978-1-58648-519-1..

- ↑ "Nixon Resigns". The Washington Post. The Watergate Story. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ↑ 1974 Congressional Record, Vol. 120, Page H29219

- ↑ Bazan, Elizabeth B (December 9, 2010), "Impeachment: An Overview of Constitutional Provisions, Procedure, and Practice", Congressional Research Service reports

- ↑ "The Legal Aftermath Citizen Nixon and the Law". Time. August 19, 1974. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Gerald Ford's Proclamation Granting a Pardon to Richard Nixon". Ford.utexas.edu. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ↑ Mary Lou Fulton (1990-07-17). "Nixon Library: Nixon Timeline-Page 2". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Kaufman, Michael T. "Peter W. Rodino Dies at 96; Led House Inquiry on Nixon", The New York Times, May 8, 2005. Accessed November 25, 2007. "Peter W. Rodino Jr., an obscure congressman from the streets of Newark who impressed the nation by the dignity, fairness, and firmness he showed as chairman of the impeachment hearings that induced Richard M. Nixon to resign as president, died yesterday at his home in West Orange, N.J. He was 95."

- 1 2 "Stateswoman Barbara Jordan – A Closeted Lesbian". Planet Out. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved July 12, 2007.

- ↑ "Voters Turn Backs on Nixon Supporters". Milwaukee Journal. November 6, 1974. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

External links

- Impeachment at Watergate.info

- Articles of Impeachment against Richard Nixon, 1974

- Judiciary Committee report – Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment Part 2, The Historical Origins of Impeachment, The intentions of the framers

- The Impeachment Inquiry – CQ Almanac 1974

- An Oral History Interview with Joseph Woods – Nixon Presidential Library and Museum