Inverted World

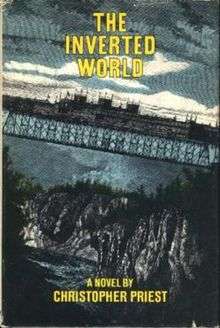

First US edition | |

| Author | Christopher Priest |

|---|---|

| Cover artist |

Andrew M. Stephenson (1st US) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science Fiction |

| Publisher |

Faber and Faber (UK) Harper & Row (US) |

Publication date | 1974 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 256 (1st UK) |

| ISBN | 0-571-10444-4 |

Inverted World (The Inverted World in some editions) is a 1974 science fiction novel by Christopher Priest, expanded from a short story by the same name included in New Writings in SF 22 (1973). In 2010, it was included in the SF Masterworks collection.

In the novel, an entire city and its people travel across a planet on railway tracks being pursued by a destructive gravitational field. The city's engineers must work to lay fresh track for the city, and pick up the old track as it moves. The ruling faction works to ensure that the people are unaware that the city is even moving. The city enters into crisis as its population decreases, the people grow unruly, and it becomes more and more difficult to stay ahead of the destructive field.

Plot

The book consists of a prologue and five parts. The first, third and fifth sections are narrated in the first person by the protagonist, Helward Mann; the second follows Helward, but is written in the third person; while the prologue and fourth part center on Elizabeth Khan, also from the third person perspective.

Helward lives in a city called "Earth", which is slowly being winched along at an average speed of 0.1 miles per day (0.16 km per day) on four railroad tracks northward toward an ever-moving, mysterious "optimum". The city, which Helward estimates is 1,500 feet (460 m) long and no more than 200 feet (61 m) high, is not on the planet Earth; the sun is disc shaped, with two spikes extending above and below its center. The city's inhabitants live in the hope of rescue from their lost home world.

Upon reaching adulthood at the age of "650 miles", Helward leaves the crèche in which he has been raised and becomes an apprentice Future Surveyor. His guild surveys the land ahead, choosing the best route. The Track Guild tears up the track south of the city to re-lay in the north. Traction is responsible for moving the city, while the Bridge-Builders overcome terrain obstacles. The Barter Guild recruits labourers ("tooks") from the primitive, poverty-stricken nearby villages they pass, as well as women brought temporarily into the city to help combat the puzzling shortfall of female babies. The Militia provides protection, armed with crossbows, against tooks resentful of the city's hard bargaining and the taking of their women.

Only guildsmen (all male) have access to the outside world and are oath-bound to keep what they know a secret; in fact, most people do not even know the city moves. Helward's wife Victoria becomes somewhat resentful when he is reluctant to answer questions about his work.

The purpose and organisation of the city is laid out in a document written by the founder: Destaine's Directive, with entries dating from 1987 to 2023. Helward reads it, but it does not satisfy his curiosity as to what the optimum is or why the city continually tries to reach it.

When Helward is assigned to escort three women back south to their village, he is astonished by what he learns about the alien nature of the world. As they go further south, the women's bodies become shorter and wider, and they begin to speak faster and in a higher pitch. The terrain itself becomes similarly squashed; mountains now look like hills to Helward. One woman has a male baby who, like Helward, does not change shape. Most frightening of all, the guildsman feels an ever-growing force pulling him southward.

Abandoning the women, with whom he now cannot even communicate, he returns to the city. There he finds that time runs at a different rate in the south. In the city, several years have passed, during which the tooks have attacked and killed many children, including Helward's son. Victoria had given him up for lost and remarried. When Helward goes to survey the land ahead, he discovers that time passes more quickly in the north.

While returning from a negotiation at a settlement, he is followed by Elizabeth Khan, herself a relative newcomer to the village. They talk for a while. When they meet again, she mentions she came from England several months before. He becomes excited, thinking that rescue is finally at hand. She is unable to convince him that they are on Earth. Intrigued, she replaces one of the village women and enters the city, which to her looks no more than a misshapen office block. Once again, she encounters Helward. Having learned about the city, she leaves to apprise her superiors and to do some research.

Two crises strike. After the took attack, it was decided to educate the residents about their situation. This, however, had an unintended effect. Dissidents called the Terminators want to stop moving the city, and are willing to resort to sabotage to achieve their goal. Victoria is one of their leaders. A more imminent problem is a large, unavoidable body of water ahead with no opposite bank visible. Both dilemmas are resolved at a meeting.

Elizabeth explains to the citizens their true situation. A global energy crisis (the "Crash") had devastated civilisation, a disaster from which the world is only gradually emerging. Destaine was a British particle physicist who had discovered a new way to generate power, but nobody had taken him seriously. The process required a natural component to work. Destaine found one such in China: the optimum. He went there to set up a test generator and was never heard of again. His invention has serious permanent and hereditary side effects, distorting people's perceptions (for example the shape of the Sun) and damaging their DNA so that fewer females are born. After nearly two centuries, the city has reached the coast of Portugal, with only the Atlantic Ocean ahead. Most of the residents are convinced, but to Elizabeth's disappointment, Helward refuses to give up his beliefs.

Critical response

The opening sentence of this novel is "I had reached the age of six hundred and fifty miles," which has gathered comment by many readers. Critic Paul Kincaid writes that "it has justly become one of the most famous in science fiction."[1] James Timarco says similarly, "From the first sentence, 'I had reached the age of 650 miles,' readers are aware that something is deeply wrong about this world. We know it has something to do with the relationship between space and time, but beyond this we can only guess."[2] Nick Owchar, in the Los Angeles Times, writes that a "reason for the story's appeal is the way in which Priest, with the novel's very first sentence, immerses us within a strange new reality... Mann's proud declaration about his maturity is a jarring revelation—time in this world is measured best by distances."[3]

Kincaid, calling the novel "one of the key works of postwar British science fiction," writes, "The inverted world is one of the few truly original ideas to have been developed in contemporary science fiction. ... In a devastatingly effective coup de théâtre, Priest produces a final revelation that twists everything that has gone before."[1]

Peter Nicholls and John Clute, in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, write that the novel "marked the climax of his career as a writer whose work resembled Genre SF, and remains one of the two or three most impressive pure-sf novels produced in the United Kingdom since World War II; the hyperboloid world on which the action takes place is perhaps the strangest planet invented since Mesklin" in Hal Clement's 1954 novel Mission of Gravity. They write that the story, dealing with paradoxes of perception and "conceptual breakthrough" (a key term in science fiction), "is a striking addition to that branch of sf which deals with the old theme of appearance-versus-reality."[4]

Timarco's review discusses the psychology of the characters and the impact on the reader:

What makes Inverted World shine like no other book is that it illustrates so perfectly how human beings create the context for their own suffering, yet this explanation never dulls the agony of Helward's predicament. And while Helward's story is tragic, the underlying narrative is hopeful. We create the chains that bind us, so therefore it must be possible for us to cast them off. But if we could do this, help one another to do it, would we know what to do when we got free?[2]

Owchar, comparing the setting with other bizarre creations by authors such as Alan Campbell and China Miéville, wonders,

Why do these fragile worlds captivate us so?

Is it because they jab at our assumptions that the modern city is entirely secure? Is it because we feel too safe just because there's concrete beneath our feet—even though concrete can wobble like rubber as it did during July's Chino Hills temblor?

Long before these philosophical considerations arise, Priest's story is fascinating for a basic, practical reason: How, indeed, does one move a city? Much of the first half of the book is devoted to describing this extraordinary process, something suggestive of the building of the Pyramids or the laying of the Transcontinental Railroad.[3]

Kirkus Reviews wrote, "The unwinding of this SF mystery is highly satisfactory, but the clever resolution is slightly deus ex futuristic machina."[5]

Awards

In 1974 The Inverted World was the winner of the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA),[6] and in 1975 it was nominated for the Hugo Award.[7]

Miscellany

- The Making of The Lesbian Horse is a short chapbook (1979) written by Priest as a parody continuation of the book.

- Cover art for the 1974 Harper & Row edition (ISBN 0-06-013421-6) was by Andrew M. Stephenson; for the 1975 Popular Library edition by Jack Faragasso.

References

- 1 2 Kincaid, Paul (2002). "Inverted World". In Fiona Kelleghan. Classics of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, Volume 1: Aegypt—Make Room! Make Room!. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. pp. 294–296. ISBN 1-58765-051-7.

- 1 2 Timarco, James (October 2008). "Inverted World by Christopher Priest". Fantasy Magazine. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- 1 2 Owchar, Nick (10 August 2008). "Christopher Priest's 'Inverted World' imagines a city that crawls". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Tribune Company. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1995). "Priest, Christopher". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin's Griffin. p. 960. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- ↑ "The Inverted World". Kirkus Reviews. 1974. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ "1974 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ↑ "1975 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

External links

- Christopher Priest's website

- The Inverted World at Worlds Without End