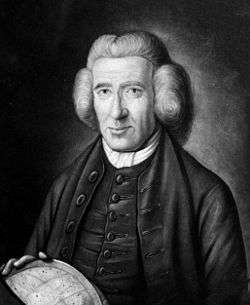

James Ferguson (Scottish astronomer)

James Ferguson (25 April 1710 – 17 November 1776) was a Scottish astronomer, instrument and globe maker.[1]

Ferguson's globes were inspired by the early 18th Century globes of John Senex. Senex sold James Ferguson the copper plates for his globe gores, but not the copper plates used for Senex's pocket globe gores. Consequently, Ferguson designed his own pocket globe, producing several editions. Ferguson had some Senex gores re-engraved by a certain James Mynde, showing Admiral Anson's voyages of the years 1740-1744.[2]

Biography

Ferguson was born near Rothiemay in Banffshire of humble parents. According to his autobiography, he learnt to read by hearing his father teach his elder brother, and with the help of an old woman was able to read quite well before his father thought of teaching him. After his father taught him to write, he was sent at the age of seven for three months to the grammar school at Keith and that was all the formal education he ever received.[3]

- ^ A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery (1764-1766), Revolutionary Players, image from Derby Museum and Art Gallery, Derby, accessed March 2011

His taste for mechanics was about this time accidentally awakened on seeing his father making use of a lever to raise a part of the roof of his house — an exhibition of strength which excited his wonder. In 1720 he was sent to a neighboring farm to keep sheep, where he amused himself by making models of machines, and at night he studied the stars. Afterwards, as a servant with a miller, and then with a doctor, he met with hardships which rendered his constitution feeble through life. Being compelled by his health to return home, he then amused himself with making a clock having wooden wheels and a whalebone spring. When slightly recovered he showed this and some other inventions to a gentleman, who employed him to clean his clocks, and to make his house his home. He there began to draw patterns for needlework, and his success in this art led him to think of becoming a painter.

In 1734 he went to Edinburgh, where he began to make portraits in miniature, by which means, while engaged in his scientific studies, he supported himself and his family for many years. Subsequently he settled at Inverness, where he drew up his Astronomical Rotula for showing the motions of the planets, places of the sun and moon, &c., and in 1743 went to London, England, which was his home for the rest of his life. He wrote various papers for the Royal Society of London, of which he became a Fellow in November 1763,[4] devised astronomical and mechanical models, and in 1748 began to give public lectures on experimental philosophy. These he repeated in most of the principal towns in England. During his time traveling in England, the notable London bookseller Andrew Millar arranged lectures for him in the spa towns of Royal Tunbridge Wells and Bath.[5] Ferguson's deep interest in his subject, his clear explanations, his ingeniously constructed diagrams, and his mechanical apparatus rendered him one of the most successful of popular lecturers on scientific subjects.

It is, however, as the inventor and improver of astronomical and other scientific apparatus, and as a striking instance of self-education, that he claims a place among the most remarkable men of science of his country. During the latter years of his life he was in receipt of a pension of £50 from the privy purse. He died in London on 17 November 1776 and was buried in St Marylebone churchyard.

Works

Ferguson's principal publications are:

- Astronomical Tables (1763)

- Lectures on Select Subjects (first edition, 1761, edited by Sir David Brewster in 1805)

- Astronomy explained upon Sir Isaac Newton's Principles (1756, edited by Sir David Brewster in 1811)

- Select Mechanical Exercises, with a Short Account of the Life of the Author, written by himself (1773).

His autobiography is included in a Life by E. Henderson, LL.D. (first edition, 1867; 2nd, 1870), which also contains a full description of Ferguson's principal inventions, accompanied with illustrations. See also The Story of the Peasant-Boy Philosopher, by Henry Mayhew (1857). A revised biography based on Hendersons "Life" but with much additional research is published in "Wheelwright of the Heavens" by John R. Millburn (In collaboration with Henry C. King) 1988.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Ferguson (1710-1776). |

- ↑

"Ferguson, James (1710-1776)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Ferguson, James (1710-1776)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - ↑ http://www.georgeglazer.com/globes/globeref/globemakers.html#ferguson

- ↑ Hockey, Thomas (2009). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660-2007" (PDF). London: The Royal Society. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- ↑ "The manuscripts, Letter from Andrew Millar to Andrew Mitchell, 26 August, 1766. See footnote no. 36.". www.millar-project.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-06-01.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ferguson, James". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ferguson, James". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Famous sons of Rothiemay

- Philosophy of Science Portal

- George Glazer Gallery

- Texts by James Ferguson on the Internet Archive (see all):

- Astronomy explained upon Sir Isaac Newton's Principles ... (2nd American edition, 1809)

- Select mechanical exercises: shewing how to construct different clocks, orreries, and sun-dials ...: to which is prefixed, a short account of the life of the author (1773)

- An easy introduction to astronomy for young gentlemen and ladies ... (2nd American edition, 1812)

- An introduction to electricity. In six sections ... (3rd ed., 1778)

- Lectures on select subjects in mechanics, hydrostatics, pneumatics, optics, and astronomy (1839 ed.)

- Tables and tracts, relative to several arts and sciences (2nd ed., 1771)

Further reading

- Laudan, Laurens (1970–80). "Ferguson, James". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 4. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 565–6. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9.