Johann Dzierzon

Johann Dzierzon, or Jan Dzierżon [ˈjan ˈd͡ʑɛrʐɔn] or Dzierżoń [ˈd͡ʑɛrʐɔɲ], also John Dzierzon (16 January 1811 – 26 October 1906), was a pioneering apiarist who discovered the phenomenon of parthenogenesis in bees and designed the first successful movable-frame beehive.

Dzierzon came from a Polish family in Silesia. Trained in theology, he combined his theoretical and practical work in apiculture with his duties as a Roman Catholic priest, before being compulsorily retired by the Church and eventually excommunicated.

His discoveries and innovations made him world-famous in scientific and bee-keeping circles, and he has been described as the "father of modern apiculture".

Nationality/ethnicity

Dzierzon came from Upper Silesia. Born into a family of ethnic Polish [1][2] background which did not speak German but a Silesian dialect of the Polish language,[3] he has been variously described as having been of Polish, German, or Silesian nationality. Dzierzon himself wrote: "As for my nationality, I am, as my name indicates, a Pole by birth, as Polish is spoken in Upper Silesia. But as I came to Breslau as a 10-year-old and pursued my studies there, I became German by education. But science knows no borders or nationality."[4]

It was at gymnasium and at the theological faculty that he became acquainted with German scientific and literary language, which he subsequently used in his scientific writings, rather than his native Polish-Silesian dialect.[3] He used Silesian-Polish in some press publications, in his private life, and in pastoral work, alongside literary Polish.[5] Dr. Jan Dzierzon considered himself a member of the Polish nation.[6][7][8]

Dzierzon's manuscripts, letters, diplomas and original copies of his works were given to a Polish museum by his nephew, Franciszek Dzierżoń.[9] Following the 1939 German invasion of Poland, many objects connected with Dzierzon were destroyed by German gendarmes on 1 December 1939 in an effort to conceal his Polish roots.[10] The Nazis made strenuous efforts to enforce a view of Dzierżoń as a German.[11]

Life

Dzierzon was born on 16 January 1811 in the village of Lowkowitz (Polish: Łowkowice), near Kreuzburg (Kluczbork), where his parents owned a farm.[12] He completed Polish elementary school before he was sent to a Protestant school located a mile from his village.[13] In 1822 he moved to Breslau (Wrocław),[14] where he attended middle school (gymnasium).[12] In 1833 he graduated from the Breslau University Faculty of Catholic Theology.[12] In 1834 he became chaplain in Schalkowitz (Siołkowice). In 1835, as an ordained Roman Catholic priest, he took over a parish in Karlsmarkt (Karłowice), where he lived for 49 years.[12]

Scientific career

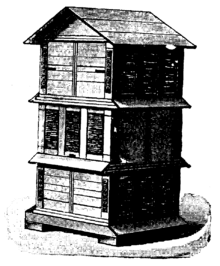

In his apiary, Dzierzon studied the social life of honeybees and constructed several experimental beehives. In 1838 he devised the first practical movable-comb beehive, which allowed manipulation of individual honeycombs without destroying the structure of the hive. The correct distance between combs had been described as 1½ inches from the center of one top bar to the center of the next one. In 1848 Dzierzon introduced grooves into the hive’s side walls, replacing the strips of wood for moving top bars. The grooves were 8 × 8 mm—the exact average between ¼ and ⅜ inch, which is the range called the "bee space." His design quickly gained popularity in Europe and North America. On the basis of the aforementioned measurements, August Adolph von Berlepsch (May 1852) in Thuringia and L.L. Langstroth (October 1852) in the United States designed their frame-movable hives.

In 1835 Dzierzon discovered that drones are produced from unfertilized eggs. Dzierzon's paper, published in 1845, proposed that while queen bees and female worker bees were products of fertilization, drones were not, and that the diets of immature bees contributed to their subsequent roles.[15] His results caused a revolution in bee crossbreeding and may have influenced Gregor Mendel's pioneering genetic research.[16] The theory remained controversial until 1906, the year of Dzierzon's death, when it was finally accepted by scientists at a conference in Marburg.[12] In 1853 he acquired a colony of Italian bees to use as genetic markers in his research, and sent their progeny "to all the countries of Europe, and even to America."[17] In 1854 he discovered the mechanism of secretion of royal jelly and its role in the development of queen bees.

With his discoveries and innovations, Dzierzon became world-famous in his lifetime.[14] He received some hundred honorary memberships and awards from societies and organizations.[12] In 1872 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Munich.[14] Other honors included the Austrian Order of Franz Joseph, the Bavarian Merit Order of St. Michael, the Hessian Ludwigsorden, the Russian Order of St. Anna, the Swedish Order of Vasa, the Prussian Order of the Crown, 4th Class, on his 90th birthday, and many more. He was an honorary member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. He also received an honorary diploma at Graz, presented by Archduke Johann of Austria. In 1903 Dzierzon was presented to Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria.[14] In 1904 he became an honorary member of the Schlesische Gesellschaft für vaterländische Kultur ("Silesian Society for Fatherland Culture").

Dzierzon's discoveries concerning asexual reproduction, as well as his questioning of papal infallibility, were rejected by the Church,[12] which in 1869 retired him from the priesthood.[18] This disagreement, along with his public engagement in local politics, led to his 1873 excommunication.[19] In 1884 he moved back to Lowkowitz, settling in the hamlet An der Grenze,[12] (Granice Łowkowskie).[20] Of his new home, he wrote:

In every direction, one has a broad and pleasant view, and I am pretty happy here, despite the isolation, as I am always close to my beloved bees — which, if one's soul be receptive to the works of the Almighty and the wonders of nature, can transform even a desert into a paradise.[12]

From 1873 to 1902 Dzierzon was in contact with the Old Catholic Church,[12] but in April 1905 he was reconciled with the Roman Catholic Church.[12]

He died in Lowkowitz on 26 October 1906 and is buried in the local graveyard.[12]

Legacy

Johann Dzierzon is considered the father of modern apiology and apiculture.[21] Most modern beehives derive from his design. Due to language barriers, Dzierzon was unaware of the achievements of his contemporary, L.L. Langstroth,[21] the American "father of modern beekeeping",[22] though Langstroth had access to translations of Dzierzon's works.[23] Dzierzon's manuscripts, letters, diplomas and original copies of his works were given to a Polish museum by his nephew, Franciszek Dzierżoń.[9]

In 1936 the Germans renamed Dzierzon's birthplace, Lowkowitz, Bienendorf ("Bee Village") in recognition of his work with apiculture.[24] At the time, the Nazi government was changing many Slavic-derived place names such as Lowkowitz. After the region came under Polish control following World War II, the village would be renamed Łowkowice.

Following the 1939 German invasion of Poland, many objects connected with Dzierzon were destroyed by German gendarmes on 1 December 1939 in an effort to conceal his Polish roots.[10] The Nazis made strenuous efforts to enforce a view of Dzierżoń as a German.[11]

After World War II, when the Polish government assigned Polish names to most places in former German territories which had become part of Poland, the Silesian town of Reichenbach im Eulengebirge (traditionally known in Polish as Rychbach) was renamed Dzierżoniów in the man's honor.[25]

In 1962 a Jan Dzierżon Museum of Apiculture was established at Kluczbork.[12] Dzierzon's house in Granice Łowkowskie(now part of Maciejów village was also turned into a museum chamber, and since 1974 his estates have been used for breeding Krain bees.[12] The museum at Kluczbork houses 5 thousand volumes of works and publications regarding bee keeping, focusing on work by Dzierzon, and presents a permanent exhibition regarding his life presenting pieces from collections from National Ethnographic Museum in Wrocław, and Museum of Silesian Piasts in Brzeg[26]

In 1966 a Polish-language plate was added to his German-language tombstone.[27]

| Inscriptions | English translation |

|---|---|

|

Hier ruht in Gott |

Here rests in God |

|

Tu spoczywa wielki uczony |

Here lies the great scientist, |

Selected works

Dzierzon's works include over 800 articles,[14] most published in Bienenzeitung[14] but also in several other scientific periodicals, and 26 books. They appeared between 1844 and 1904,[14] in German and Polish. The most important include:

- 15 November 1845: Chodowanie pszczół - Sztuka zrobienica złota, nawet z zielska, in: Tygodnik Polski Poświęcony Włościanom, Issue 20, Pszczyna (Pless).[28]

- 1848-1852: Theorie und Praxis des neuen Bienenfreundes. ("Theory and Practice of the Modern Bee-friend")[29]

- 1851 and 1859: Nowe udoskonalone pszczelnictwo księdza plebana Dzierżona w Katowicach na Śląsku - 2006 reprint[30][31]

- 1852: Nachtrag zur Theorie und Praxis des neuen Bienenfreundes (Appendix to "Theory and Practice"), C. H. Beck'sche Buchhandlung, Nördlingen,[32]

- 1853: Najnowsze pszczelnictwo. Lwów[33]

Magazines published by Dzierzon:

- 1854-1856: Der Bienenfreund aus Schlesien ("The Bee-friend from Silesia")[34][35]

- 1861-1878: Rationelle Bienenzucht ("Rational apiculture")[36][37]

Articles published by Dzierzon since 1844 in Frauendörfer Blätter, herausgegeben von der prakt. Gartenbau-Gesellschaft in Bayern, redigirt von Eugen Fürst[38] ("Frauendorf News" of the Bavarian Gardeners Society) were collected by Rentmeister Bruckisch from Grottkau (Grodków) and re-published under the titles:

- Neue verbesserte Bienen-Zucht des Johann Dzierzon ("New improved bee-breeding, of John Dzierzon"), Brieg 1855

- Neue verbesserte Bienen-Zucht des Pfarrers Dzierzon zu Carlsmarkt in Schlesien ("New improved bee-breeding, of priest Dzierzon at Carlsmarkt in Silesia"), Ernst'sche Buchhandlung, 1861[39]

- Lebensbeschreibung von ihm selbst, vom 4. August 1885 (abgedruckt im Heimatkalender des Kreises Kreuzburg/OS 1931, S. 32-28), 1885 (Dziergon's own biography, reprinted in 1931)[40]

- Der Zwillingsstock ("Semi-detached beehive"), E. Thielmann, 1890[41][42]

English translations:

- Dzierzon's rational bee-keeping; or The theory and practice of dr. Dzierzon of Carlsmarkt, Translated by H. Dieck and S. Stutterd, ed. and revised by C. N. Abbott, Published by Houlston & sons, 1882[43]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ "britannica.com". britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ↑ Cimała, Bogdan (1992). "Kluczbork: dzieje miasta (Kluczbork, City History)". Instytut Śląski.

- 1 2 Stanisław Feliksiak, Słownik biologów polskich, Polish Academy of Sciences Instytut Historii Nauki, Oświaty i Techniki, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p. 149.

- ↑ Dados, Danuta; Tomaszewski, Roman. "Historia znana i nieznana. Materiały do dziejów pszczelnictwa w Polsce - Ślązak Cz. II". Pasieka (in Polish and German). Archived from the original on 2012-03-05. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ↑ Kwartalnik opolski, vol. 31, Opolskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk, 1985, p. 86.

- ↑ L. Brożek "Jan Dzierżon. Studium monograficzne" Opole 1978

- ↑ A. Gładysz "Jan Dzierżoń, pszczelarz o światowej sławie" Katowice 1957

- ↑ H. Borek i S. Mazak "Polskie pamiątki rodu Dzierżoniów" Opole 1983

- 1 2 Danuta Kamolowa, Krystyna Muszyńska, Zbiory rękopisów w bibliotekach i muzeach w Polsce, Biblioteka Narodowa (Polish National Library, p. 68.

- 1 2 Mówią wieki: magazyn historyczny (The Ages Speak: Magazine of History, [published by] the Polish Historical Society), vol. 23 (1980), p. 26.

- 1 2 "Komunikaty: Seria monograficzna, tomy 2-11". Instytut Śląski w Opolu. 1960. p. 138.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Kudyba, Teresa (2008). "Prawda ponad wszystko (The Truth above All)" (PDF) (in German). Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ↑ Zygmunt Antkowiak, Patroni ulic Wrocławia, Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1982.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dados, Danuta; Tomaszewski, Roman. "Pasieka (Apiary) 1/2007. Historia znana i nieznana. Materiały do dziejów pszczelnictwa w Polsce - Ślązak Cz. II" (in Polish). pasieka.pszczoly.pl. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ↑ Everett Mendelsohn; Garland E. Allen (2002). Science, history, and social activism. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-0495-7.

- ↑ Alfred Henry Sturtevant; Edward B. Lewis (2001). A history of genetics. CSHL Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-607-8.

- ↑ Eva Crane. The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-92467-2.

- ↑ "Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 4th edition" (in German). 5. Leipzig. 1885–89: 268. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ↑ Wit Chmielewski. "World-Famous Polish Beekeeper - Dr. Jan Dzierzon (1811-1906) and his work in the centenary year of his death" (PDF). Journal of Apicultural Research, Volume 45, Number 3, 2006. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ↑ "kluczbork.pl". kluczbork.pl. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- 1 2 Crane, Eva (1999). The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting. Taylor & Francis. p. 421. ISBN 978-0415924672.

- ↑ Cincinnati Historical Society; Cincinnati Museum Center; Filson Historical Society (2005). Ohio Valley history. The journal of the Cincinnati Historical Society. 5–6. Cincinnati Museum Center. p. 96.

- ↑ Crane, Eva (1999). The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting. Taylor & Francis. pp. 421–422. ISBN 0415924677.

- ↑ "Niemcy "przechrzcili” miejscowość znaną pod polską nazwą w całym świecie (Łowkowice = Bienendorf)", Ilustrowany Kuryer Codzienny, no. 280, 8 October 1936.

- ↑ "Dzierżoniów". Britanica Encyclopaedia, 15th edition. p. 312. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Muzeum im. Jana Dzierżona w Kluczborku". Kluczbork.pl. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ↑ "willisch.eu". Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ↑ Scan of Article, signed Dzierzoń, online at digitalsilesia.eu (zip-File of djvu-Images)

- ↑ at Google Books

- ↑ at Google Books

- ↑ , p. 829, at Google Books

- ↑ at Google Books

- ↑ , p. 379, at Google Books

- ↑ at Google Books

- ↑ , p. 109, at Google Books

- ↑ at Google Books

- ↑ at Google Books

- ↑ , p. 118, at Google Books

- ↑ at Google Books

- ↑ Archived December 8, 2004, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ at Google Books

- ↑ , p. RA1-PA45, at Google Books

- ↑ at Google Books

Further reading

- L. Brożek "Jan Dzierżon. Studium monograficzne" Opole 1978

- W. Kocowicz i A. Kuźba "Tracing Jan Dzierżon Passion" Poznań 1987

- A. Gładysz "Jan Dzierżon, pszczelarz o światowej sławie" Katowice 1957

- H. Borek i S. Mazak "Polskie pamiątki rodu Dzierżoniów" Opole 1983

- W. Chmielewski "World-Famous Polish Beekeeper - Dr. Jan Dzierżon (1811-1906) and his work in the centenary year of his death" in Journal of Apicultural Research, Volume 45(3), 2006

- S. Orgelbrand "Encyklopedia ..." 1861

- “ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture” 1990, article Dzierzon pg 147

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Johann Dzierzon. |

- Rational Bee-keeping online English translation of Jan Dzierzon's book (London: Houlston & sons, 1882)

- Jan Dzierżon at History of Kluczbork

- Jan Dzierżon Museum in Kluczbork (Polish)

- Jan Dzierżon Museum in Kluczbork

- Church Records of Lowkowitz, Silesia from 1765- 1948, where Johann Dzierzon was born in 1811 and died in 1906