1978 smallpox outbreak in the United Kingdom

The 1978 smallpox outbreak in the United Kingdom claimed the life of Janet Parker (1938–1979), a British medical photographer, who became the last recorded person to die from smallpox. Her illness and death, which was connected to the deaths of two other people, led to an official government inquiry and triggered radical changes in how dangerous pathogens were studied in the UK.[1][2] The government inquiry into Parker's death by R.A. Shooter[3] found that while working at the University of Birmingham Medical School,[4][5] she was accidentally exposed to a strain of smallpox virus that had been grown in a research laboratory on the floor below her workplace, and that the virus had most likely spread from that laboratory through ducting. Shooter's conclusion on how the virus had spread was challenged in court when the University of Birmingham was prosecuted by the Health and Safety Executive for breach of Health and Safety legislation.[6]

Janet Parker

Life and work

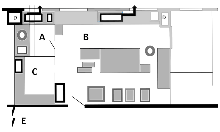

Born in March 1938,[7] Parker was the only daughter[8] of Frederick and Hilda Witcomb (née Linscott).[7] She was married to Joseph Parker, a Post Office engineer,[9] and lived in Burford Park Road, Kings Norton, Birmingham, UK. After several years as a police photographer she joined the University of Birmingham Medical School, where she was employed as a medical photographer in the Anatomy Department. Janet Parker often worked in a darkroom above a laboratory where research on smallpox viruses was being conducted.[10]

Smallpox is an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants named Variola major and Variola minor.[11] The last naturally occurring infection was of Variola minor in Somalia in 1977.[12] At the time of Janet Parker's death, the laboratory at University of Birmingham Medical School was conducting research on variants of smallpox virus known as "whitepox viruses",[13] which were considered to be a threat to the success of the World Health Organisation's smallpox eradication programme.[14]

Illness and death

On 11 August 1978, Parker (who had been vaccinated against smallpox in 1966[15]) fell ill; she had a headache and pains in her muscles. She developed spots that were thought to be a benign rash.[9] On 20 August at 3pm, she was admitted to East Birmingham (now Heartlands) Hospital and a clinical diagnosis of Variola major, the most serious type of smallpox, was made by Professor Alasdair Geddes and Dr. Thomas Henry Flewett.[16] By this time the rash had spread and covered all Parker's body, including the palms of her hands and soles of her feet, and it was confluent on her face.[17] At 10pm she was on her way to Catherine-de-Barnes Isolation Hospital near Solihull. By 11pm all her close contacts, including her parents, were placed in quarantine. Her parents were later also transferred to Catherine-de-Barnes.[9] The next day, poxvirus infection was confirmed by electron microscopy of vesicle fluid. Parker died of smallpox at Catherine-de-Barnes on 11 September 1978.[9][18]

For Janet Parker's funeral, special disease control measures had to be put into place.[19] Undertaker Ron Fleet was sent to Catherine-de-Barnes to collect her body and later described his memories: "When the day of the funeral arrived, the cars were given an escort by unmarked police vehicles just in case there was an accident...The body had to be cremated because there was a chance the virus could have thrived in the ground if Mrs Parker had been buried. All other funerals were cancelled that day and the Robin Hood Crematorium was thoroughly cleaned afterwards."[20]

Reactions

Controlling the infection

Many people had close contact with Parker before she was admitted to hospital. The outbreak resulted in 260 people being immediately quarantined, several of them at Catherine-de-Barnes Hospital, including the ambulance driver who transported Mrs Parker.[18] On 26 August, health officials went to Parker's place in Burford Park Road, Kings Norton, and fumigated her home and car.[9] On 28 August, five hundred people were placed in quarantine in their homes for two weeks.[9] Of those potentially infected, only Parker's mother, Hilda Witcomb,[7] contracted the disease but survived. The other close contacts, which included two Biomedical Scientists from the Birmingham Regional Virus Laboratory based at East Birmingham Hospital, were released from quarantine in Catherine-de-Barnes on 10 October 1978.[9]

Over a year later, in October 1979, the university authorities fumigated the Medical School East Wing.[9] The ward at Catherine-de-Barnes Hospital in which Janet Parker had died was still sealed off five years after her death, all the furniture and equipment inside left untouched.[9]

A similar outbreak had occurred at the University of Birmingham Medical School in 1966, when Tony McLennan, who was also a medical photographer and worked in the same laboratory later used by Janet Parker, contracted smallpox. He had a milder form of the disease, which was not diagnosed for eight weeks.[9] He was not quarantined and there were at least twelve further cases in the West Midlands, five of whom were quarantined in Witton Isolation Hospital in Birmingham.[21] There are no records of any formal enquiries on the source of this earlier outbreak despite concerns expressed by the then Head of the Laboratory, Professor P. Wildy.[17]

Related deaths

On 5 September 1978, Janet Parker's 71-year-old father, Frederick Witcomb, of Myrtle Avenue, Kings Heath, died while in quarantine at Catherine-de-Barnes Hospital.[8][18] He appeared to have died following a cardiac arrest when visiting his daughter.[22] No post-mortem was carried out on his body because of the risk of smallpox infection.[9]

On 6 September 1978, Professor Henry Bedson, then Head of the Microbiology Department at the University of Birmingham Medical School and son of Sir Samuel Phillips Bedson,[23] committed suicide while in quarantine at his home in Cockthorpe Close, Harborne.[18] He cut his throat in the garden shed and died at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham a few days later. His suicide note read "I am sorry to have misplaced the trust which so many of my friends and colleagues have placed in me and my work."[24] In 1977, the World Health Organisation (WHO) had told Henry Bedson that his application for his laboratory to become a Smallpox Collaborating Centre had been rejected. This was partly because of safety concerns; the WHO wanted as few laboratories as possible handling the virus.[25]

Government inquiry

An official government inquiry into Parker's death was led by microbiologist R.A. Shooter,[17] whose report was debated by British Parliament.[26] Since Shooter's Report of the investigation into the cause of the 1978 Birmingham smallpox occurrence also played an important role in the court case against the university for breach of safety legislation,[9] its official publication was postponed until the outcome of the trial was known.

The Shooter Report was published in 1980. It noted that Bedson had failed to inform the authorities of changes in his research that could have affected safety. Shooter's inquiry discovered that the Dangerous Pathogens Advisory Group had inspected the laboratory on two occasions and each time recommended that the smallpox research be continued there, despite the fact that the facilities at the laboratory fell far short of those required by law. Several of the staff at the laboratory had received no special training. Inspectors from the World Health Organisation had told Bedson that the physical facilities at the laboratory did not meet WHO standards, but had nonetheless only recommended a few changes in laboratory procedure. Bedson misled the WHO about the volume of work handled by the laboratory, telling them that it had progressively declined since 1973, when in fact it had risen substantially as Bedson tried to finish his work before the laboratory closed.[27] Shooter also found that while Janet Parker had been vaccinated, she had not been vaccinated recently enough to protect her against smallpox.[17]

The report concluded that Parker had probably been infected by a strain of smallpox virus called Abid (named after the three-year-old Pakistani boy from whom it had originally been isolated), which was being handled in the smallpox laboratory during 24–25 July 1978. The virus had travelled in air currents up a service duct from the laboratory below, to a room in the Anatomy Department that was used for telephone calls. On 25 July, Parker had spent much more time there than usual ordering photographic materials because the financial year was about to end.[17]

Legal prosecution

On 1 December 1978 the Health and Safety Executive announced their intention to prosecute the university for breach of safety legislation.[9] The case was heard in November 1979. Expert evidence, presented by the defence and accepted by the magistrates, showed that sufficient virus material could not be produced by the laboratory to generate an infectious dose in the telephone room where Parker was supposedly infected.[28] Although the source of infection was traced, the mode of transmission was not.[29][30] The defence witnesses claimed that 11,812 gallons of virus suspension would have been required to generate an infectious dose in the telephone room.[28] Although the Shooter Inquiry noted the poor state of sealing of ducting in the laboratory, this was caused after the outbreak by engineers fumigating the laboratory and ducts.[9] The university was found not guilty of causing Parker's death. In August 1981, following a formal claim for damages made by the trade union Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs in 1979, Parker's husband, Joseph, was awarded £25,000 in compensation.[9]

Research practice

In light of this incident, all known stocks of smallpox were destroyed or transferred to one of two WHO reference laboratories which had BSL-4 facilities; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR in Koltsovo, Russia.[31]

See also

- Rahima Banu, last person infected with naturally occurring Variola major

- Ali Maow Maalin, last person infected with naturally occurring Variola minor

- List of unusual deaths

References

- ↑ Hawkes N (1979). "Smallpox death in Britain challenges presumption of laboratory safety". Science. 203 (4383): 855–6. Bibcode:1979Sci...203..855H. doi:10.1126/science.419409. PMID 419409.

- ↑ UK Department of Health,

- ↑ Report of the investigation into the cause of the 1978 Birmingham smallpox occurrence

- ↑ Glynn, Jenifer; Glynn, Ian (2004). The life and death of smallpox. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 0-521-84542-4.

- ↑ Pennington, Hugh. Smallpox Scares London Review of Books 24: 32–33 (accessed 16 February 2013)

- ↑ Behbehani, A.M. (1983). "The smallpox story: life and death of an old disease". Microbiol. Rev. 47 (4): 455–509. PMC 281588

. PMID 6319980.

. PMID 6319980. - 1 2 3 "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Frederick Witcomb".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Toxic SHOCK; Twenty five years ago a disease that many thought was dead and gone reared its head in Birmingham: smallpox. Campbell Docherty and Caroline Foulkes look back at the 1978 outbreak and ask if it could ever happen again.".

- ↑ Glynn, Jenifer; Glynn, Ian (2004). The life and death of smallpox. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 0-521-84542-4.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, Sherris JC, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 525–8. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ "Smallpox". WHO Factsheet. Archived from the original on 2007-09-21.

- ↑ Dumbell KR, Kapsenberg J. Laboratory investigation of two `whitepox' viruses and comparison with two variola strains from southern India. Bull WHO 1982; 60: 381±7.

- ↑ Henderson DA (1987). "Principles and lessons from the smallpox eradication programme". Bull. World Health Organ. 65 (4): 535–46. PMC 2491023

. PMID 3319270.

. PMID 3319270. - ↑ "SARS Cases in Asia Show Labs' Risks (washingtonpost.com)".

- ↑ "The smallpox death that locked down Birmingham could have been avoided" in Birmingham Mail 2016, accessed 23 September 2016

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Report of the investigation into the cause of the 1978 Birmingham smallpox occurrence

- 1 2 3 4 Smallpox Threat: Preparations bring back memories of outbreak, in Birmingham Mail 2002 (online), accessed 12 August 2015

- ↑ Ron Fleet from Sheldon, who at the time of Janet Parker's death worked for Solihull funeral director Bastocks and later for the BBC at Pebble Mill, recalled that he was told that authorities would not allow the body to be stored in a fridge in case the virus managed to multiply: "I was expecting to retrieve the body from a fridge in the mortuary, but (...) it was stored in a body bag that was kept on the floor of a garage away from the main hospital building. She was in a transparent body bag packed with wood shavings and sawdust. There was also some kind of liquid and I remember that I was frightened that the bag would split open. The body was covered in sores and scars - it was quite horrific. I was on my own and I needed help to lift the body (...) but I managed to get her into the van. People from the hospital were very wary of helping me." - quoted from Brett Gibbons, Haunting Memories of Smallpox Drama, in Birmingham Mail, 21 June 2011 (online), accessed 12 August 2015

- ↑ Brett Gibbons, Haunting Memories of Smallpox Drama, in Birmingham Mail, 21 June 2011 (online), accessed 12 August 2015

- ↑ "Smallpox".

- ↑ Geddes AM (2006). "The history of smallpox". Clinics in Dermatology. 24 (3): 152–7. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.11.009. PMID 16714195.

- ↑ Sir Samuel Phillips Bedson, Fellow of the Royal Society,(1886–1969),

- ↑ Stockton

- ↑ "Hugh Pennington · Diary: Smallpox Scares: Bioterrorism · LRB 5 September 2002". London Review of Books.

- ↑ "Smallpox Virus (Shooter Report)".

- ↑ Lawrence McGinty (4 January 1979). New Scientist. Reed Business Information. pp. 12–. ISSN 0262-4079.

- 1 2 Behbehani, A.M. (1983). "The smallpox story: life and death of an old disease". Microbiol. Rev. 47 (4): 455–509. PMC 281588

. PMID 6319980.

. PMID 6319980. - ↑ Hawkes N (1979). "Smallpox death in Britain challenges presumption of laboratory safety". Science. 203 (4383): 855–6. Bibcode:1979Sci...203..855H. doi:10.1126/science.419409. PMID 419409.

- ↑ UK Department of Health,

- ↑ Connor, Steve (2002-01-03). "How terrorism prevented smallpox being wiped off the face of the planet for ever". London: The Independent. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

Bibliography

- Jonathan B. Tucker, Scourge: The Once and Future Threat of Smallpox (Grove Press) 2002 (online)

- Altman, Lawrence K (11 February 1979). "Criticism Is Leveled in Aftermath of Fatal British Smallpox Outbreak; Debate Over Storing of Virus Laboratory Chief Killed Himself Heavy Workload Is Cited". The New York Times. p. 34.

- Shooter, R. A. (July 1980). "Report of the investigation into the cause of the 1978 Birmingham smallpox occurrence" (PDF). London: H. M. Stationery Office.

- Stockton, William (4 February 1979). "Smallpox is not dead". The New York Times Magazine.

External links

- Portrait photograph (pre-1978) of Janet Parker (online)

- 1978 newspaper article Smallpox virus escapes (online)

- 1978 newspaper article about Janet Parker's father being taken into quarantine (online)

- 1978 newspaper article about Janet Parker's mother being released from quarantine (online)