Candi of Indonesia

A candi (pronounced [tʃandi]) is a Hindu or Buddhist temple in Indonesia, mostly built during the zaman Hindu-Buddha or "Indianized period", between the 4th to 15th centuries.[1]

The Great Dictionary of the Indonesian Language of the Language Center defines a candi as an ancient stone building used for worship, or for storing the ashes of cremated Hindu or Buddhist kings and priests.[2] Indonesian archaeologists describe candis as sacred structures of Hindu and Buddhist heritage, used for religious rituals and ceremonies in Indonesia.[3] However, ancient secular structures such as gates, urban ruins, pools and bathing places are often called "candi" too, while a shrine that specifically serves as a tomb is called a "cungkup".[1]

In Hindu Balinese architecture, the term candi refer to a stone or brick structure of single-celled shrine with portico, entrance and stairs, topped with pyramidal roof and located within a pura. It is often modeled after East Javanese temples, and functions as a shrine to a certain deity. To the Balinese, a candi is not necessarily ancient, since candis continue to be (re-)built within these puras, such as the reconstructed temple in Alas Purwo, Banyuwangi.[4]

In contemporary Indonesian Buddhist perspective, candi also refers to a shrine, either ancient or new. Several contemporary viharas in Indonesia for example, contains the actual-size replica or reconstruction of famous Buddhist temples, such as the replica of Pawon[5] and Plaosan's perwara (small) temples. In Buddhism, the role of a candi as a shrine is sometimes interchangeable with a stupa, a domed structure to store Buddhist relics or the ashes of cremated Buddhist priests, patrons or benefactors. Borobudur, Muara Takus and Batujaya for example are actually elaborate stupas.

In modern Indonesian language, the term candi can be translated as "temple" or similar structure, especially of Hindu and Buddhist faiths. Thus temples of Cambodia (such as the Angkor Wat), Champa (Central and Southern Vietnam), Thailand, Myanmar and India are called as candi too in Indonesian.

Terminology

Candi refers to a structure based on the Indian type of single-celled shrine, with a pyramidal tower above it, and a portico.[7] The term Candi is given as a prefix to the many temple-mountains in Indonesia, built as a representation of the Cosmic Mount Meru, an epitome of the universe. However, the term also applied to many non-religious structures dated from the same period, such as gopura (gates), petirtaan (pools) and some of habitation complexes. Examples of non-temple candis are the Bajang Ratu and Wringin Lawang gates of Majapahit. The Candi Tikus bathing pool in Trowulan and Jalatunda in Penanggungan slopes, as well as the remnants of non-religious habitation and urban structures such as Ratu Boko and some of Trowulan city ruins, are also considered candi.

"Between the 7th and 15th centuries, hundred of religious structures were constructed of brick and stone in Java, Sumatra and Bali. These are called candi. The term refers to other pre-Islamic structures including gateways and even bathing places, but its principal manifestation is the religious shrine."

In ancient Java, a temple was probably originally called prāsāda (Sanskrit: प्रासाद), as evidence in the Manjusrigrha inscription (dated from 792 CE), that mentioned "Prasada Vajrasana Manjusrigrha" to refer to the Sewu temple.[9]:89 The term prasad itself refer to a sacred offering or a sacrament.[10] This term is in par with Cambodian and Thai term prasat which refer to the towering structure of a temple.

Etymology

From Hindu perspective, the term "candi" itself is believed was derived from Candika, one of the manifestations of the goddess Durga as the goddess of death.[11] This suggests that in ancient Indonesia the "candi" had mortuary functions as well as connections with the afterlife. The association of the name "candi", candika or durga with Hindu-Buddhist temples is unknown in India and other parts of Southeast Asia outside of Indonesia, such as Cambodia, Thailand, or Burma.

Another theory from Buddhist perspective, suggested that the term "candi" might be a localized form of the Pali word cedi (Sanskrit: caitya) — which related to Thai word chedi which refer to a stupa, or it might be related to the bodhisattva Candī (also known as Cundī or Candā).[12]

Historians suggest that the temples of ancient Java were also used to store the ashes of cremated deceased kings or royalty. This is in line with Buddhist concept of stupas as structures to store Buddhist relics, including the ashes and remains of holy Buddhist priests or the Buddhist king, patrons of Buddhism. The statue of god stored inside the garbhagriha (main chamber) of the temple is often modeled after the deceased king and considered to be the deified person of the king portrayed as Vishnu or Shiva according to the concept of devaraja. The example is the statue of king Airlangga from Belahan temple portrayed as Vishnu riding Garuda.

Architecture

The candi architecture follows the typical Hindu architecture traditions based on Vastu Shastra. The temple layout, especially in central Java period, incorporated mandala temple plan arrangements and also the typical high towering spires of Hindu temples. The candi was designed to mimic Meru, the holy mountain the abode of gods. The whole temple is a model of Hindu universe according to Hindu cosmology and the layers of Loka.[13]

Structure elements

The candi structure and layout recognize the hierarchy of the zones, spanned from the less holy to the holiest realms. The Indic tradition of Hindu-Buddhist architecture recognize the concept of arranging elements in three parts or three elements. Subsequently, the design, plan and layout of the temple follows the rule of space allocation within three elements; commonly identified as foot (base), body (center), and head (roof). The three zones is arranged according to a sacred hierarchy. Each Hindu and Buddhist concepts has their own terms, but the concept's essentials is identical. Either the compound site plan (horizontally) or the temple structure (vertically) consists of three zones:[14]

- Bhurloka (in Buddhism: Kāmadhātu), the lowest realm of common mortals; humans, animals also demons. Where humans still bound by their lust, desire and unholly way of life. The outer courtyard and the foot (base) part of each temples is symbolized the realm of bhurloka.

- Bhuvarloka (in Buddhism: Rupadhatu), the middle realm of holy people, rishis, ascetics, and lesser gods. People here began to see the light of truth. The middle courtyard and the body of each temples is symbolized the realm of bhuvarloka.

- Svarloka (in Buddhism: Arupadhatu), the highest and holiest realm of gods, also known as svargaloka. The inner courtyard and the roof of each temples is symbolized the realm of svarloka. The roof of Hindu structure usually crowned with ratna (sanskrit: jewel) or vajra, or in eastern Java period, crowned by cube structure. While stupa or dagoba cylindrical structure served as the pinnacle of Buddhist ones.

Style

Soekmono, an Indonesian archaeologist, has classified the candi styles into two main groups: a central Java style, which predominantly date from before 1,000 CE, and an eastern Java style, which date from after 1,000 CE. He groups the temples of Sumatra and Bali into the eastern Java style.[15]

| Parts of the temple | Central Java Style | Eastern Java Style |

|---|---|---|

| Shape of the structure | Tends to be bulky | Tends to be slender and tall |

| Roof | Clearly shows stepped roof sections, usually consist of 3 parts | The multiple parts of stepped sections formed a combined roof structure smoothly |

| Pinnacle | Stupa (Buddhist temples), Ratna or Vajra (Hindu temples) | Cube (mostly Hindu temples), sometimes Dagoba cylindrical structures (Buddhist temples) |

| Portal and niches adornment | Kala-Makara style; Kala head without lower jaw opening its mouth located on top of the portal, connected with double Makara on each side of the portal | Only Kala head sneering with the mouth complete with lower jaw located on top of the portal, Makara is absent |

| Relief | Projected rather high from the background, the images was done in naturalistic style | Projected rather flat from the background, the images was done in stylized style similar to Balinese wayang image |

| Layout and location of the main temple | Concentric mandala, symmetric, formal; with main temple located in the center of the complex surrounded by smaller perwara temples in regular rows | Linear, asymmetric, followed topography of the site; with main temple located in the back or furthermost from the entrance, often located in the highest ground of the complex, perwara temples is located in front of the main temple |

| Direction | Mostly faced east | Mostly faced west |

| Materials | Mostly andesite stone | Mostly red brick |

There are material, form, and location exceptions to these general design traits. While the Penataran, Jawi, Jago, Kidal and Singhasari temples, for example, belong to the eastern Java group, they use andesite stone similar to the central Java temple material. Temple ruins in Trowulan, such as Brahu, Jabung and Pari temples use red brick. Also the Prambanan temple is tall and slender similar to the east Java style, yet the roof design is central Javan in style. The location also do not always correlate with the temple styles, for example Candi Badut is located in Malang, East Java, yet the period and style belongs to older 8th century central Javanese style.

The earlier northern central Java complexes, such as the Dieng temples, are smaller and contain only several temples which exhibit simpler carving, whereas the later southern complexes, such as Sewu temple, are grander, with a richer elaboration of carving, and concentric layout of the temple complex.

The Majapahit period saw the revival of Austronesian megalithic design elements, such stepped pyramids (punden berundak). These design cues are seen in the Sukuh and Cetho temples in Mount Lawu in eastern Central Java, and in stepped sanctuary structures on the Mount Penanggungan slopes that are similar to meso-American stepped pyramids.

Materials

Most of well-preserved candi in Indonesia are made from andesite stone. This is mainly owed to the stone's durability compared to bricks, against tropical weathers and torrential rains. Nevertheless, in certain period, especially Majapahit era, saw the extensive use of red brick as temple and building materials. The materials commonly used in temple construction in Indonesia are:

- Andesite is an extrusive igneous volcanic rock, of intermediate composition, with aphanitic to porphyritic texture. The colour of this lava rock ranged from light to dark grey. Andesite is especially abundant in the volcanic island of Java, mined from a certain cliffs or stone quarry with andesite deposit formed from compressed ancient magma chamber or cool down lava spill. Each of andesite stones are custom made into blocks with interlocking technique, to construct temple walls, floors and building. Andesite stones are easily formed and carved with iron chisel, making it a suitable material for temple walls and decorations carved as bas-reliefs. The walls of andesite stone was then carved with exquisite narrative bas-reliefs, which can be observed in many temples, especially in Borobudur and Prambanan. Andesite rocks are also used as the material for carved statues; the images of deities and Buddha.

- Brick is also used to construct temple. The oldest brick temple structure is Batujaya temple compound in Karawang, West Java, dated from 2nd to 12th century CE. Although brick had been used in the candi of Indonesia's classical age, it was Majapahit architects of the 14th and 15th centuries who mastered it.[16] Making use of a vine sap and palm sugar mortar, their temples had a strong geometric quality. The example of Majapahit temples are Brahu temple in Trowulan, Pari in Sidoarjo, Jabung in Probolinggo. Temples of Sumatra, such as Bahal temple, Muaro Jambi, and Muara Takus are also made from bricks. However, compared to lava andesite stone, clay red bricks are less durable, especially if exposed to hot and humid tropical elements and torrential monsoon rain. As the result many of red bricks structures were crumbling down over centuries, and the reconstruction efforts requires to recast and replace the damaged structure with new block of bricks.

- Tuff is also a volcanic rock that is also quite abundant near Javanese volcanoes or limestone formations. In Indonesian and Javanese languages, tuff is called batu putih (white stone), which corresponds to its light color. The chalky characteristic of this stone however, has made this stone unsuitable to be carved into bas-reliefs of building ornaments. Compared to andesite, tuff is considered as an inferior quality building material. In Javanese temples, tuff usually are used as stone fillings; forming the inner structure of the temple, while the outer layer employed andesite that is a more suitable material to be carved. The tuff quarries can be found in Sewu limestone ranges near Ratu Boko hill. The tuff fillings in the temple can be examined in Ratu Boko crematorium temple. Tuff also used as building material of outer walls of temple compound, such as those walls found buried around Sewu and Sambisari temple.

- Stucco is materials similar to modern concrete, made from the mixture of sand, stone and water, and sometimes ground clamshell. The stucco as temple building material is observable in Batujaya temple compound in West Java.

- Plaster called vajralepa (Sanskrit: diamond plaster) is used to coat the temple walls. The white-yellowish plaster is made from the mixture of ground limestone, tuff or white earth (kaolin), with plant substances such as gums or resins as binder. The varjalepa white plaster was applied upon the andesite walls, and then painted with bright colors, serving perhaps as a beacon of Buddhist teaching.[17] The traces of worn-off vajralepa plaster can be observed in Borobudur, Sari, Kalasan and Sewu temple walls.

- Wood is also believed to be used in some of candi construction, or at least as parts of temple building material. Sari and Plaosan temples for example are known to have traces stone indentions to support wooden beams and floors in its second floor, as well as traces of wooden stairs. Ratu Boko compound has building bases and stone umpak column base, which suggests that the wooden capitals once stood there to support wooden roof structure made of organic materials. Traces of holes to install wooden window railings and wooden doors are also observable in many of the perwara (complementary smaller) temples. Of course wooden materials are easily decayed in humid tropical climate, leaving no traces after centuries.

Motif and decoration

Kala-Makara

The candis of ancient Java are notable with the application of kala-makara as both decorative and symbolic elements of the temple architecture. Kala is the giant symbolizing time, by making kala's head as temple portals element, it symbolizes that time consumes everything. Kala is also a protective figure, with fierce giant face it scares away malevolent spirits. Makara is a mythical sea monster, the vahana of sea-god Varuna. It has been depicted typically as half mammal and half fish. In many temples the depiction is in the form of half fish or seal with the head of an elephant. It is also shown with head and jaws of a crocodile, an elephant trunk, the tusks and ears of a wild boar, the darting eyes of a monkey, the scales and the flexible body of a fish, and the swirling tailing feathers of a peacock. Both kala and makara are applied as the protective figures of the temple's entrance.

Kala is the giant head, often takes place on top of the entrance with makaras projected on either sides of kala's head, flanking the portal or projecting on the top corner as antefixes. The kala-makara theme also can be found on stair railings on either sides. On the upper part of stairs, the mouth of kala's head projecting makara downward. The intricate stone carving of twin makaras flanking the lower level of stairs, with its curved bodies forming the stair's railings. Other than makaras, kala's head might also project its tongue as stair's railings. These types of stair-decorations can be observed in Borobudur and Prambanan. Makara's trunks are often describes as handling gold ornaments or spouting jewels, while in its mouth often projected Gana dwarf figures or animals such as lions or parrots.

Linga-Yoni

In ancient Javanese candi, the linga-yoni symbolism was only found in Hindu temples, more precisely those of Shivaist faith. Therefore, they are absent in Buddhist temples. The linga is a phallic post or cylinder symbolic of the god Shiva and of creative power. Some lingas are segmented into three parts: a square base symbolic of Brahma, an octagonal middle section symbolic of Vishnu, and a round tip symbolic of Shiva. The lingas that survive from the Javanese classical period are generally made of polished stone of this shape.

Lingas are implanted in a flat square base with a hole in it, called a yoni, symbolic of the womb and also represents Parvati, Shiva's consort. A yoni usually has a kind of spout, usually decorated with nāga, to help channeled and collects the liquids poured upon linga-yoni during Hindu ritual. As a religious symbol, the function of the linga is primarily that of worship and ritual. Oldest remains of linga-yoni can be found in Dieng temples from earlier period circa 7th century. Originally each temples might have a complete pair of linga-yoni unity. However, most of the times, the linga is missing.

In the tradition of Javanese kingship, certain lingas were erected as symbols of the king himself or his dynasty, and were housed in royal temples in order to express the king's consubstantiality with Shiva. The example is the linga-yoni of Gunung Wukir temple, according to Canggal inscription is connected to King Sanjaya from the Mataram Kingdom, in 654 Saka (732 CE).[18] Other temples that contains complete linga-yoni include Sambisari and Ijo temples. Eastern Javanese temples that contains linga-yoni are Panataran and Jawi temple, although the linga is missing.

Bas-reliefs

The walls of candi often displayed bas-reliefs, either serves as decorative elements as well as to convey religious symbolic meanings; through describing narrative bas-reliefs. The most exquisite of the temple bas-reliefs can be found in Borobudur and Prambanan temples. The first four terrace of Borobudur walls are showcases for bas-relief sculptures. These are exquisite, considered to be the most elegant and graceful in the ancient Buddhist world.[19] The Buddhist scriptures describes as bas-reliefs in Borobudur such as Karmavibhangga (the law of karma), Lalitavistara (the birth of Buddha), Jataka, Avadana and Gandavyuha. While in Prambanan the Hindu scriptures is describes in its bas-relief panels; the Ramayana and Bhagavata Purana (popularly known as Krishnayana).

The bas-reliefs in Borobudur depicted many scenes of daily life in 8th-century ancient Java, from the courtly palace life, hermit in the forest, to those of commoners in the village. It also depicted temple, marketplace, various flora and fauna, and also native vernacular architecture. People depicted here are the images of king, queen, princes, noblemen, courtier, soldier, servant, commoners, priest and hermit. The reliefs also depicted mythical spiritual beings in Buddhist beliefs such as asuras, gods, boddhisattvas, kinnaras, gandharvas and apsaras. The images depicted on bas-relief often served as reference for historians to research for certain subjects, such as the study of architecture, weaponry, economy, fashion, and also mode of transportation of 8th-century Maritime Southeast Asia. One of the famous renderings of an 8th-century Southeast Asian double outrigger ship is Borobudur Ship.

There are significant distinction of bas-reliefs' style and aesthetics between the Central Javanese period (prior of 1000 CE) and East Javanese period (after 1000 CE). The earlier Central Javanese style, as observable in Borobudur and Prambanan, are more exquisite and naturalistic in style. The reliefs is projected rather high from the background, the images was done in naturalistic style with proper ideal body proportion. On the other hand, the bas-reliefs of Eastern Javanese style is projected rather flat from the background, the images was done in stiffer pose and stylized style, similar to currently Balinese wayang images. The East Javanese style is currently preserved in Balinese art, style and aesthetics in temple bas-reliefs, also wayang shadow puppet imagery, as well as the Kamasan painting.

Deities

Kalpataru and Kinnaras

The images of coupled Kinnara and Kinnari can be found in Borobudur, Mendut, Pawon, Sewu, Sari, and Prambanan temples. Usually, they are depicted as birds with human heads, or humans with lower limbs of birds. The pair of Kinnara and Kinnari usually is depicted guarding Kalpataru (Kalpavriksha), the tree of life, and sometimes guarding a jar of treasure. There are bas-relief in Borobudur depicting the story of the famous kinnari, Manohara.

The lower outer wall of Prambanan temples were adorned with row of small niche containing image of simha (lion) flanked by two panels depicting bountiful kalpataru (kalpavriksha) tree. These wish-fulfilling sacred trees according to Hindu-Buddhist beliefs, is flanked on either side by kinnaras or animals, such as pairs of birds, deer, sheep, monkeys, horses, elephants etc. The pattern of lion in niche flanked by kalpataru trees is typical in Prambanan temple compound, thus it is called as "Prambanan panel".

Boddhisattva and Tara

In Buddhist temples, the panels of bas-reliefs usually adorned with exquisite images of male figure of Bodhisattvas and female figure of Taras, along with Gandarvas heavenly musicians, and sometimes the flock of Gana dwarfs. These are the deities and divinities in Buddhist beliefs, which resides in the Tushita heaven in Buddhism cosmology. The notable images of boddhisattvas could be found adorning outer walls of Plaosan, Sari, Kalasan, Pawon and of course Borobudur temple.

Devata and Apsara

In Hindu temples, the celestial couple; male Devatas and female Apsaras are usually found adorns the panels of temple's walls. They are the Hindu counterpart of Buddhist Bodhisattva-Tara celestial beings. On the other side of narrative panels in Prambanan, the temple wall along the gallery were adorned with the statues and reliefs of devatas and brahmin sages. The figure of lokapalas, the celestial guardians of directions can be found in Shiva temple. The Brahmin sage editors of veda were carved on Brahma temple wall, while in Vishnu temple the figures of a male deities devatas flanked by two apsaras. The depiction of celestial beings of lesser gods and goddesses — devatas and apsaras, describes the Hindu concept of sacred realm of Svargaloka. This is corresponds to the concept of the towering Hindu temple as the epitome of Mount Meru in Hindu cosmology.

Guardians

Dvarapala

.jpg)

Most of larger temple compound in ancient Java were guarded by a pair of Dvarapala statues, as gate guardians. The twin giants usually placed flanked the entrance in front of the temple, or in four cardinal points. Dvarapala took form of two fierce giants or demons that ward off evil and malevolent spirits from entering the sacred temple compounds. In Central Javanese art, Dvarapala is mostly portrayed as a stout and rather chubby giant, with fierce face of glaring round goggle eyes, protruding fangs, curly hairs and moustaches, with fat and round belly. The giant usually depicted as holding gada and sometimes knives as weapon.

In East Javanese art and Balinese version however, the dvarapala usually depicted rather slender, with the exception of gigantic dvarapala of Singhasari near Malang, East Java that measures 3.7 metres tall. The most notable dvarapala statues are those of candi Sewu, each pair guarding four cardinal points of the grand temple complex, making them a total eight large dvarapala statues in perfect condition. The dvarapalas of Sewu temple has become the prototype of Gupolo guardian in later Javanese art, copied as guardians in Javanese keratons of Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Another fine example is two pairs of dvarapala guarding the twin temples of Plaosan.

Lion

The statues of a pair of lion (Sanskrit:Siṁha, Indonesian and Javanese:Singa) flanked the portal, are often placed as the guardians in candi entrance. Lions were never native animals of Southeast Asia in recorded history. As the result the depiction of lion in ancient Southeast Asian art, especially in ancient Java and Cambodia, is far from naturalistic style as depicted in Greek or Persian art counterparts, since and all based on perception and imagination. The cultural depictions and the reverence of lion as the noble and powerful beast in Southeast Asia was influenced by Indian culture especially through Buddhist symbolism.

Statue of a pair of lions often founds in temples in Southeast Asia as the gate guardian. In Borobudur Buddhist monument Central Java, Indonesia andesite stone statues of lions guarding four main entrances of Borobudur. The thrones of Buddha and Boddhisattva found in Kalasan and Mendut Buddhist temples of ancient Java depicted elephant, lion, and makara. The statue of winged lion also found in Penataran temple East Java.

Stupa and Ratna pinnacles

The religions dedicated in the temples of ancient Java can be easily distinguished mainly from its pinnacles on top of the roof. Bell-shaped stupa can be found on the Buddhist temples' roof, while ratna, the pinnacle ornaments symbolize gem, mostly founds in Hindu temples.

The typical stupas in Javanese classical temple architecture is best described as those of Borobudur style; the bell-shaped stupa. The stupa in Borobudur upper round terrace of Arupadhatu consist of round lotus pedestal, gently sloped bell-shaped dome, rectangular shape on top of the dome serves as the base of hexagonal pinnacle. Each stupa is pierced by numerous decorative openings, either in the shape of rectangular or rhombus. Statues of the Buddha sit inside the pierced stupa enclosures. Borobudur was first thought more likely to have served as a stupa, instead of a temple. A stupa is intended as a shrine for the Buddha. Sometimes stupas were built only as devotional symbols of Buddhism. A temple, on the other hand, is used as a house of worship.

Ratna pinnacle took form of a curved obtuse pyramidal shape or sometimes cylindrical, completed with several base structure or pedestals took form as some ornamental seams (Javanese:pelipit). It can be found as the pinnacle of both Hindu and Buddhist temples. Nevertheless, it is most prevalent in Hindu temples. The example of temple with ratna pinnacle is Sambisari and Ijo temple. In Prambanan, the stylized vajra replaced ratna as the temple's pinnacles. In later periods, the false lingga-yoni, or cube can be found in Hindu temple's roof, while cylindrical dagoba on top of Buddhist counterparts.

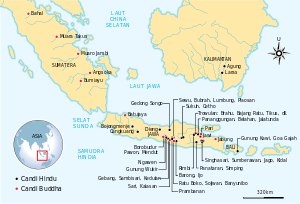

Location

The high concentration of candi can be found especially dense in Sleman Regency in Yogyakarta, also Magelang and Klaten in Central Java; which corresponds to the historical region of Kedu Plain (Progo River valley, Temanggung-Magelang-Muntilan area) and Kewu Plain (Opak River valley, around Prambanan), the cradle of Javanese civilization. Other important sites with notable temple compounds includes Malang, Blitar and Trowulan areas in East Java. West Java also contains a small number of temples such as Batujaya and Cangkuang. Outside of Java, the candi type of temple can be found in Bali, Sumatra, and Southern Kalimantan, although they are quite scarce. In Sumatra, two exceptional sites are notable for its temple density; the Muaro Jambi Temple Compounds in Jambi and Padang Lawas or Bahal complex in North Sumatra.

The candis might be built on plain or uneven terrain. Prambanan and Sewu temples for example, are built on even flat low-lying terrain, while the temples of Gedong Songo and Ijo are built on hill terraces on higher grounds or mountain slopes. Borobudur on the other hand is built upon a bedrock hill. The position, orientation and spatial organization of the temples within the landscape, and also their architectural designs, were determined by socio-cultural, religious and economic factors of the people, polity or the civilization that built and support them.[20]

Java

West Java

- Batujaya, a compound of Buddhist Stupa made from red brick and mortar located at Batu Jaya, Karawang, West Java. Probably dated back to Tarumanagara kingdom in the 6th century AD.[21]

- Cibuaya, a compound of Vishnuite Hindu temples made from red brick and mortar also located at Batu Jaya, Karawang, West Java.[22] Probably linked to Tarumanagara kingdom in the 6th century AD.

- Bojongmenje, ruins of Hindu temple in Rancaekek, Bandung Regency.

- Candi Cangkuang, the only one of the few surviving West Java's Hindu temple at Leles, Garut, West Java. Located on an island in the middle of a lake covered by water lilies. Unlike other Javanese temple characteristics by grand architecture, Cangkuang temple is more modest with only one structure still standing.[23] Shiva statue faces east toward the sunrise. Date uncertain.

Central Java

Dieng Plateau

The Hindu temple compound located in Dieng Plateau, near Wonosobo, Central Java. Eight small Hindu temples from the 7th and 8th centuries, the oldest in Central Java. Surrounded by craters of boiling mud, colored lakes, caves, sulphur outlets, hot water sources and underground channels. The temples are:

- Arjuna temple

- Semar temple

- Srikandi temple

- Puntadewa temple

- Sembadra temple

- Dwarawati temple

- Gatotkaca temple

- Bima temple

Gedong Songo

South-west of Semarang, Central Java. Five temples constructed in 8th and 9th centuries. The site highlights how, in Hinduism, location of temples was as important as the structures themselves. The site has panoramas of three volcanoes and Dieng Plateau.

Borobudur and Kedu Plain

The Kedu Plain lies to the north west of Yogyakarta and west of Gunung Merapi and south west of Magelang, in Central Java.

- Borobudur. 9th-century Buddhist monument, reportedly the world's largest. Seven terraces to the top represent the steps from the earthly realm to Nirvana. Reliefs of the birth, enlightenment and death of the Buddha. A UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Pawon. 8th-century Buddhist temple.

- Mendut. 8th-century Mahayana Buddhist temple.

- Ngawen. Five aligned sanctuaries, one decorated with finely sculpted lions. 8th-century Buddhist temple located east from Mendut temple. The name linked to Venuvana, "the temple of bamboo forest".

- Banon. 8th-century Hindu temple located north from Pawon temple. The few remains make it impossible to reconstruct the temple. The Hindu god statue from this temple is now located at the National Museum in Jakarta.

- Umbul, a 9th-century bathing complex in Grabag, Magelang

- Gunung Sari. Ruins of three secondary temples and the foot of the main temple remain.

- Gunung Wukir. One of the oldest inscriptions on Java, written in 732 CE, found here. Only the bases remain of the main sanctuary and three secondary temples.

Slopes of Merapi

- Sengi complex. Three temples, Candi Asu, Candi Pendem and Candi Lumbung, Sengi, on the side of Mount Merapi. 8th and 9th century. The base of the temple has a climbing plant motif.

- Gebang

- Morangan

- Pustakasala

- Lawang

Near Yogyakarta

- Candi Sambisari. 10th century underground Hindu temple buried by eruptions from Mount Merapi for a century. Discovered in 1966 by a farmer plowing his field.

- Candi Kadisoka, uncompleted 8th-century temple buried by eruptions from Merapi. Thought to have been Hindu temple, discovered in 2000.

Prambanan Plain

- Roro Jonggrang, the main Prambanan complex. 9th century Hindu temple called the "Slender Maiden". Main temple dedicated to Shiva flanked by temples to Visnu and Brahma. Reliefs depict Ramayana stories.

- Sewu. Buddhist temple complex, older than Roro Jonggrang. A main sanctuary surrounded by many smaller temples. Well preserved guardian statues, replicas of which stand in the central courtyard at the Jogja Kraton.

- Candi Lumbung. Buddhist temple ruin located south from Sewu temple, consisting of one main temple surrounded by 16 smaller ones.

- Candi Gana. Buddhist temple ruin rich in statues, bas-reliefs and sculpted stones. Frequent representations of children or dwarfs with raised hands. Located east from Sewu complex in the middle of housing complex. Under restoration since 1997.

- Plaosan. Buddhist temple compound located few kilometers east from Sewu temple, probably 9th century. Thought to have been built by a Hindu king for his Buddhist queen. Two main temples with reliefs of a man and a woman. Slender stupa.

- Arca Bugisan. Seven Buddha and bodhisattva statues, some collapsed, representing different poses and expressions.

- Sajiwan. Buddhist temple decorated with reliefs concerning education. The base and staircase are decorated with animal fables.

- Candi Sari. Once a sanctuary for Buddhist priests. 8th century. Nine stupas at the top with two rooms beneath, each believed to be places for priests to meditate.

- Candi Kalasan. 8th-century Buddhist temple built in commemoration of the marriage of a king and his princess bride, ornamented with finely carved reliefs.

- Candi Kedulan. Discovered in 1994 by sand diggers, 4m deep. Square base of main temple visible. Secondary temples not yet fully excavated.

Ratu Boko and surrounds

- Ratu Boko Built between 8th and 9th centuries. Mixed Buddhist and Hindu style. Partially restored palace auditorium. Ruins of the royal garden with a bathing pool inside.

- Arca Gopolo. A group of seven statues in a circle, as if in assembly. Flower decoration on the clothes of the largest are still visible.

- Banyunibo. A small 9th-century Buddhist complex. A main temple surrounded by six smaller ones forming a stupa. Restoration completed in 1978.

- Candi Barong. Two almost identical temples on terraces. Believed to be 9th century Hindu and part of a sacred complex, of which they were the crown.

- Dawangsari. Perhaps the site of a destroyed Buddhist stupa, now reduced to an array of andesite stones.

- Candi Ijo. A complex of three-tiered temples, but only one has been renovated. A main sanctuary and three secondary shrines with statues. Still under reconstruction.

- Watugudig. A group of pole sittings in the shape of a Javanese gong. About 40 have been discovered, but others may remain buried. Locals believe this to be the resting place of King Boko.

- Candi Abang. Actually a well that looks like a pyramid with very tall walls. In some aspects looks like Borobudur. Unique atmosphere.

- Candi Gampingan. Ruins 1.5m underground of a temple and stairs. Reliefs of animals at the foot of the temple are believed to be a fable.

- Sentono. At the base of Abang temple. Perhaps younger than other regional temples. Complex of caves with two mouths. Statue and bas-relief in left chamber.

- Situs Payak. The best preserved bathing place in Central Java. 5m below ground. Thought to be Hindu.

Klaten Regency

East of Yogyakarta, Central Java.

- Candi Merak. Two 10th century Hindu temples, rich in reliefs and decorations, in the middle of a village.

- Candi Karangnongko. Difficult to date because remains are few.

Mount Lawu

Near Surakarta, Central Java.

- Candi Cetho. On the slopes of Mount Lawu. A 15th-century Hindu temple 1470m above sea level.

- Candi Sukuh. On the slopes of Mount Lawu. 15th-century Hindu complex resembling a Mayan temple. Reliefs illustrate life before birth and sex education.

East Java

Malang area

Malang, East Java.

- Candi Badut. Small Shivaite temple dating from the 8th century.

- Candi Songgoriti. Very similar to Candi Sembrada at Dieng, this Hindu temple is located in a valley between mount Arjuna and Mount Kawi, East Java

- Candi Jago. Late 13th century. Terraces decorated with reliefs in the distinctive (Javanese shadow puppet) style with scenes from the Mahabharata epic and underworld demons.

- Candi Singosari. Dedicated to the kings of the Singosari Dynasty (1222 to 1292 AD), the precursors of the Majapahit Kingdom, it was built in 1304.

- Arca Dwarapala.Dedicated to the kings of the Singosari Dynasty (1222 to 1292 AD).

- Candi Kidal.

- Candi Singosari.

- Candi Sumberawan.

- Candi Rambut Monte.

- Candi Selakelir.

Blitar area

- Candi Penataran. East Java's only sizable temple complex, with a series of shrines and pavilions. Constructed 12th through 15th centuries. Believed to be the state temple of the Majapahit Empire.

- Candi Bacem

- Candi Boro

- Candi Kalicilik

- Candi Kotes

- Candi Wringin Branjang

- Candi Sawentar

- Candi Sumbernanas

- Candi Sumberjati or Candi Simping

- Candi Gambar Wetan

- Candi Plumbangan

- Candi Tepas

Kediri area

- Candi Surowono is a small temple, of the Majapahit Kingdom, located in the Canggu Village of the Kediri (near Pare) district in Java, Indonesia. It was believed to have been built in 1390 AD as a memorial to Wijayarajasa, the Prince of Wengker.

- Candi Tegowangi

- Arca Totok Kerot

- Arca Mbah Budho

- Candi Dorok

- Candi Tondowongso

- Gua Selomangleng

- Gua Selobale

- Calon Arang Site is a site who inspired Leak dance in Bali Indonesia

- Babadan or SumberCangkring Site

- Prasasti Pohsarang

- Candi Setono Gedong and today a mosque

Sidoarjo, Tretes, and Probolinggo areas

- Candi Pari, in Sidoarjo. Dated from 1293 Saka (1371 CE), this Majapahit red brick temple bear similarity with Champa architecture.

- Candi Sumur, in Sidoarjo. Located just a hundred meters from Candi Pari, probably built in the same era.

- Candi Jawi, Tretes. A 13th-century funerary temple. Slender Shiva-Buddhist shrine completed around 1300.

- Penanggungan sites, Mount Penanggungan, which has terraced sanctuaries, meditation grottoes and sacred pools, about 80 sites in all including Candi Belahan believed to be the burial site of King Airlangga, who died in 1049.

- Candi Jabung, east of Probolinggo, near Kraksaan. According to the inscription on the top of the temple portal, Jabung dates from 1276 saka (1354 CE).

Trowulan

- Candi Tikus, Trowulan. Trowulan was once the capital of the Majapahit kingdom, the controller of most of the important ports of the day. Survived thanks to a sophisticated irrigation system. Tikus held run-off water from Mount Penanggungan for sanctification rites. Site also contains parts of the palace gate, entryway and water system.

- Candi Brahu, Trowulan. Location the temple front of Bubat Area in Majapahit Palace environment (7°32'33.85"S, 112°22'28.01"E). Brahu Temple is a budhis temple, built at 15 a.c and restored during 1990 and was finished during 1995. There was no accurate note the function of the temple.

- Candi Gentong, Trowulan. Location the temple 350m east of Brahu temple(7°32'38.05"S, 112°22'40.65"E). Many Ceramic from Ming and Yuan Dynasty founded in this temple area. There was no accurate note the function of the temple.

- Candi Muteran, Trowulan. Location the temple north of Brahu temple ( 7°32'27.72"S, 112°22'29.41"E). There was no accurate note the function of the temple.

- Kolam Segaran, Trowulan. Segaran pond is Majapahit Heritage (7°33'29.55"S,112°22'57.54"E) The Pond was found during 1926 by Ir.Maclain Pont. First restoration was 1966, finished at 1984. The function of this pond was as the place of recreation and to greet the foreign guest. This was the biggest ancient pond founded in Indonesia.

- Gapura Bajang Ratu, Trowulan.

- Gerbang Wringin Lawang, Trowulan.

Bali

- Candi Gunung Kawi. Located in Sebatu village, Tampak Siring area, Gianyar regency. It is one of the oldest temple in Bali dated from 989 CE, the five temples is carved on the stone slopes forming grottoes.

- Candi Kalibukbuk. Located in Kalibukbuk village, Buleleng regency. It is one of the few Buddhist temple in Hindu dominated Bali. The temple is thought to be dated from the 8th century.

Sumatra

Kalimantan

- Candi Agung, North Hulu Sungai, South Kalimantan, a Hindu Candi. South Kalimantan was a base of Hindu Kingdom of Negara Dipa, which then inherited by Negara Daha.

- Candi Laras, Tapin, South Kalimantan, a Buddhist Candi. Buddhist Kingdom in South Kalimantan was represented by the kingdom of Tanjung Puri.

Gallery

-

Borobudur the largest Buddhist monument in the world

-

Mendut temple near Borobudur

-

Pawon temple between Borobudur and Mendut

-

Prambanan, the largest Hindu Temple in Indonesia

-

Lumbung

-

Kalasan temple near Prambanan

-

Sari temple

-

Plaosan Kidul

-

Sambisari

-

Banyunibo

-

Candi Bima, Dieng Plateau

-

Candi Puntadewa, Dieng Plateau

-

Candi Arjuna, Dieng Plateau

-

Candi Srikandi, Dieng Plateau

-

Candi Gatotkaca, Dieng Plateau

-

Candi Semar, Dieng Plateau

-

Candi Gedong Song, Ungaran

-

Candi Gebang,Yogyakarta

-

Sukuh

-

Kidal

-

Jago

-

Blandongan, Batujaya, West Java

-

CandiTikus, Trowulan

-

Candi Wringin Lawang, Trowulan

-

Gumpung, Muaro Jambi, Jambi

-

Muara Takus, Riau

-

Candi Plumbangan, Blitar, East Java

See also

- Architecture of Indonesia

- Ancient temples of Java

- Hindu temple architecture

- Buddhist architecture

- Wat, temples in Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos

- Bujang Valley, an archaeological site in Kedah, Malaysia, where more than fifty candi have been discovered

References

- 1 2 Soekmono (1995), p. 1

- ↑ "Candi". KBBI (in Indonesian).

- ↑ Sedyawati (2013), p. 1

- ↑ Tomi Sujatmiko (9 June 2013). "Peninggalan Majapahit Yang Tersembunyi di Alas Purwo". Kedaulatan Rakyat (in Indonesian).

- ↑ "Replika Candi Pawon". Vihāra Jakarta Dhammacakka Jaya.

- ↑ "Prasada". Sanskrit dictionary.

- ↑ Philip Rawson: The Art of Southeast Asia

- ↑ Soekmono, R. "Candi:Symbol of the Universe", pp.58-59 in Miksic, John, ed. Ancient History Volume 1 of Indonesian Heritage Series Archipelago Press, Singapore (1996) ISBN 978-981-3018-26-6

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ↑ "प्रसाद". Hindi-English dictionary.

- ↑ Soekmono, Dr R. (1973). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 81. ISBN 979-413-290-X.

- ↑ "History of Women in Buddhism - Indonesia: Part 10". Shakyadita: Awakening Buddhist Women.

- ↑ Sedyawati (2013), p. 4

- ↑ Konservasi Borobudur (in Indonesian)

- ↑ Soekmono, Dr R. (1973). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 86. ISBN 979-413-290-X.

- ↑ Schoppert, P.; Damais, S. (1997). Didier Millet, ed. Java Style. Paris: Periplus Editions. pp. 33–34. ISBN 962-593-232-1.

- ↑ "The Greatest Sacred Buildings". Museum of World Religions, Taipei. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ "Candi Gunung Wukir". Southeast Asian Kingdoms. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Cockrem, Tom (May 18, 2008). "Temple of enlightenment". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 November 2011 – via The Buddhist Channel.tv.

- ↑ Degroot (2009), p. 2

- ↑ Sedyawati (2013), p. 36

- ↑ Sedyawati (2013), p. 38

- ↑ "Garut: The Hidden Beauty of West Java". The jakarta post.

Bibliography

- Soekmono, R. (1995). Jan Fontein, ed. The Javanese Candi: Function and Meaning, Volume 17 from Studies in Asian Art and Archaeology, Vol 17. Leiden: E.J. BRILL. ISBN 9789004102156.

- Degroot, Véronique (2009). Candi, Space and Landscape: A Study on the Distribution, Orientation and Spatial Organization of Central Javanese Temple Remains. Leiden: Sidestone Press, Issue 38 of Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde. ISBN 9789088900396.

- Sedyawati, Edi; Santiko, Hariani; Djafar, Hasan; Maulana, Ratnaesih; Ramelan, Wiwin Djuwita Sudjana; Ashari, Chaidir (2013). Candi Indonesia: Seri Jawa (in Indonesian and English). Jakarta: Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan. ISBN 9786021766934.

Further reading

- Dumarcay, J. 1986 Temples of Java Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press

- Holt, C. 1967 Art in Indonesia Ithaca: Cornell University

- Patt, J.A. 1979 The Uses and Symbolism of Water in Ancient Indonesian Temple Architecture University of California, Berkeley (unublished PhD thesis)

- Prijotomo, J. 1984 Ideas and Forms of Javanese Architecture Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press

- Degroot, Véronique 2009 Candi, Space and Landscape: A Study on the Distribution, Orientation and Spatial Organization of Central Javanese Temple Remains Leiden: Sidestone Press, Issue 38 of Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, ISBN 9088900396