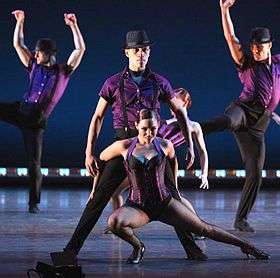

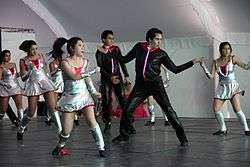

Jazz dance

Jazz dance developed alongside jazz music in New Orleans in the early 1900s.[1] The steps and essential style of this dance, however, originated from dances of Africans brought to the Americas as slaves.[2][3] Originally, the term jazz dance encompassed any dance done to jazz music, including both tap dance and jitterbug.

Over time, a clearly defined jazz genre emerged, changing from a street dance to a theatrical dance performed on stage by professionals. Some scholars and dancers, especially Swing and Lindy Hop dancers, still regard the term jazz dance as an umbrella term which includes both the original and the evolved versions: they refer to the theatrical form of jazz dance as modern jazz.

History

The term jazz dance was first used to describe dances done to the new-fangled jazz music of the early 20th century, but its origin lie in the dances brought from Africa by slaves shipped to America. At that time, it referred to any dance done to jazz music, which included both tap dance and jitterbug. A defining feature was its "free conversation-like style of improvisation." [4]

Beginning in the 1930s and continuing through the 1960s, jazz dance transformed from its street form into a theatre-based performance art.[5][6] During this time, choreographers from other genres experimented with the style.,[5] including George Balanchine, Agnes de Mille, Jack Cole, Hanya Holm, Helen Tamiris, Michael Kidd, Jerome Robbins, and Bob Fosse.[5] All of these choreographers influenced jazz by requiring highly trained dancers, and introducing steps from ballet and contemporary dance.[1][5] In the 1950s, jazz dance was profoundly influenced by Caribbean and Latin American influences introduced by Katherine Dunham.[7]

New Orleans

New Orleans was an incubator of jazz dance because it was a melting pot of so many cultures.

Jazz in New Orleans developed with community life such as brass band funerals and music in park picnics or ball games. The spirit of New Orleans and jazz music connected the performer to the audience, offering a link through which all parties could participate; this allowed for the growth of dance around the city's musical style.[8] In New Orleans, big bands in the 1930s and 1940s made a living by playing in large ballrooms, amusement parks, hotels, and other venues for dancing.[9]

Kinney's Hall or McKenna's Hall, known to ragtime musicians and dancers as Funky Butt Hall,[10] was a church/dance hall that housed many weekend dances. It was popular because of Buddy Bolden and his band, one of the biggest musicians to have an influence on the development of Jazz music, and directly dance. Bolden popularized the ragtime song "Funky Butt", which gave the hall its common name.

Economy Hall, a dance hall located in Treme, near Storyville, where dances were held because of the numerous social aid and pleasure clubs that had events in the hall. These organizations provided a variety of services, including brass band funerals and dances, to New Orleans community.[8]

Although jazz dance is more commonly used to refer to the theatrical style these days, many swing dancers still claim ownership of the term jazz dance. In modern times, many professionals have moved to New Orleans in an attempt to kick-start a revision of the neo-swing dance movement.[11]

Elements

(This section refers to elements of Modern Jazz Dance. The elements of other jazz styles can be found in detail on their own entries (Tap Dance, Jitterbug, Swing (dance), Lindy Hop)

Isolations are a quality of movement that were introduced to jazz dance by Katherine Dunham.[12]

A low center of gravity and high level of energy are other important identifying characteristics of jazz dance.[12] Other elements of jazz dance are less common and are the stylizations of their respective choreographers.[12] One such example are the inverted limbs and hunched-over posture of Bob Fosse.[12]

Notable directors, dancers, and choreographers

- Michael Bennett, director, writer, choreographer, and dancer who was a tony award winner. A Chorus Line and Dream Girls are examples of some of his work.

- Busby Berkley, movie choreographer in the 1930s and 1940s famous for geometric pattern and kaleidoscopic arrangements

- Jack Cole, considered the father of jazz dance technique.[13] He was a key inspiration to Matt Mattox, Bob Fosse, Jerome Robbins, Gwen Verdon, and many other choreographers. He is credited with popularizing the theatrical form of jazz dance with his great number of choreographic works on television and Broadway.[14]

- Katherine Dunham, an anthropologist, choreographer, and pioneer in Black theatrical dance. She introduced isolations jazz dance.[7][12]

- Eugene Louis Facciuto (a.k.a. "Luigi"), an accomplished dancer who, after suffering a crippling automobile accident in the 1950s, created a new style of jazz dance based on the warm-up exercises he invented to circumvent his physical handicaps. The exercise routine he created for his own rehabilitation became the world's first complete technique for learning jazz dance.

- Bob Fosse, a noted jazz choreographer who created a new form of jazz dance that was inspired by Fred Astaire and the burlesque and vaudeville styles.

- Patsy Swayze, choreographer and dance instructor, combining Jazz and Ballet. Swayze founded the Houston Jazz Ballet Company and served as the ballet's director.[15]

- Gus Giordano, an influential jazz dancer and choreographer, known for his clean, precise movement qualities.[12]

- Michael Jackson, known as "The King of Pop"

- Leon James, authentic Jazz dancers from the 1930s original member of "Whitey's Lindy Hoppers

- Gene Kelly, award winning dance film icon. Known for continuing his career for over 60 years. Work can be found in Singin' in the Rain and On the Town.

- Frankie Manning, Lindy Hop and authentic Jazz dancer and choreographer

- Norma Miller, known worldwide as the "Queen of Swing" Lindy Hop and authentic Jazz dancer and choreographer

- Al Minns, authentic Jazz dancers from the 1930s original member of "Whitey's Lindy Hoppers

- Jerome Robbins, choreographer for a number of hit musicals, including Peter Pan, The King and I, Fiddler on the Roof, Gypsy, Funny Girl, and West Side Story.

- Gwen Verdon, known for her roles in Damn Yankees, Chicago, and Sweet Charity.

- David Winters known for his role as A-Rab in West Side Story and as an award-winning choreographer for movies and TV programs.

See also

References

- 1 2 Barnes, Clive (Aug 2000). "Who's Jazzy Now?". Dance Magazine: 90.

- ↑ Borade, Gaynor. "You'll Be Amazed to Know the Long and Varied History of Jazz Dance". Buzzle. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ Barnes, Clive. "Attitudes." Dance Magazine. Aug. 2004: 98. Web.

- ↑ Carter, Curtis. "Improvisation in Dance." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 58, no. 2, 181-90. Accessed April 24, 2015. jstor.org.

- 1 2 3 4 Boross, Bob (Aug 1999). "All That's Jazz.". Dance Magazine: 54.

- ↑ Hayes, Hannah. "Educators Make a Case for Keeping the History Alive in the Studio." Dance Teacher. Sep. 2009: 58. Web.

- 1 2 "Katherine Dunham's Brilliant Legacy." The Art of Dance. WordPress.com, 13 Dec 2009. Web. 1 May 2012 http://theartofdance.wordpress.com/2009/12/13/katherine-dunham%E2%80%99s-brilliant-legacy/

- 1 2 "A New Orleans Jazz History, 1895-1927." New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park, Louisiana, April 5, 2015, accessed April 4, 2015.

- ↑ Crease, Robert. "Divine Frivolity: Hollywood Representations of the Lindy Hop, 1937-1942." In Representing Jazz. Durham: Duke University Press, 1995.

- ↑ "Streetswings Dance History Archives: Funky Butt". Sonny Watson's Street Swing. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Reid, Molly. "New Orleans a Haven for Swing Dance Beginners, Professionals." The Times-Picayune, January 21, 2010, accessed April 26, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 White, Ariel. "Jazz Movers and Shakers." Dance Spirit. Sep. 2008: 101. Web.

- ↑ "Jack Cole: Jazz (documentary)". Dance Films Association. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ↑ "Jack Cole." Dance Heritage. Dance Heritage Coalition, n.d. Web. 1 May 2012. http://www.danceheritage.org/cole.html

- ↑ Nelson, Valerie J. (15 September 2009). "Patrick Swayze dies at 57; star of the blockbuster films 'Dirty Dancing' and 'Ghost'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

Bibliography

- Eliane Seguin, Histoire de la danse jazz, 2003, Editions CHIRON, ISBN 978-2-7027-0782-1, 281 pp

- Jennifer Dunning, Alvin Ailey: A Life in Dance, 1998, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-80825-8, 468 pp

- A. Peter Bailey, Revelations: The Autobiography of Alvin Ailey, 1995, Carol Pub. Group, ISBN 978-0-8065-1861-9, 183 pp

- Margot L. Torbert, Teaching Dance Jazz, Margot Torbert, 2000, ISBN 978-0-9764071-0-2

- Robert Cohan, The Dance Workshop, Gaia Books Ltd, 1989, ISBN 978-0-04-790010-5

- Crease, Robert. Divine Frivolity: Hollywood Representations of the Lindy Hop, 1937-1942. In Representing Jazz. Durham: Duke University Press, 1995.

- Carter, Curtis. Improvisation in Dance. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 58, no. 2, 181-90. Accessed April 24, 2015. jstor.org.

- A New Orleans Jazz History, 1895-1927. New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park, Louisiana, April 5, 2015

- Reid, Molly. New Orleans a Haven for Swing Dance Beginners, Professionals. The Times-Picayune, January 21, 2010