Jefferson Parish, Louisiana

| Jefferson Parish, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

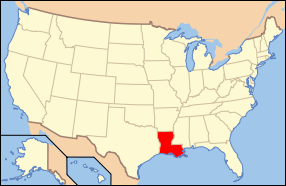

Location in the U.S. state of Louisiana | |

Louisiana's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | February 11, 1825 |

| Named for | President Thomas Jefferson |

| Seat | Gretna |

| Largest community | Metairie |

| Area | |

| • Total | 665 sq mi (1,722 km2) |

| • Land | 296 sq mi (767 km2) |

| • Water | 370 sq mi (958 km2), 56% |

| Population (est.) | |

| • (2013) | 434,767 |

| • Density | 1,463/sq mi (565/km²) |

| Congressional districts | 1st, 2nd, 6th |

| Time zone | Central: UTC-6/-5 |

| Website |

www |

Coordinates: 29°44′N 90°06′W / 29.733°N 90.100°W

Jefferson Parish (French: Paroisse de Jefferson) is a parish in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2010 census, the population was 432,552.[1] The parish seat is Gretna.[2]

Jefferson Parish is included in the New Orleans-Metairie, LA Metropolitan Statistical Area. Jefferson Parish was less affected by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and has rebounded at a more rapid pace than neighboring Orleans Parish. (Jefferson Parish also surpassed Orleans Parish in population for that reason, and it is now the second-most-populous parish in the state, behind East Baton Rouge Parish.)

History

1825 to 1940

Jefferson Parish was named in honor of US President Thomas Jefferson[3] of Virginia when the parish was established by the Louisiana Legislature on February 11, 1825, a year before Jefferson died. A bronze statue of Jefferson stands at the entrance of the General Government Complex on Derbigny Street at the parish seat in Gretna. The parish seat was in the City of Lafayette, until that city was annexed by New Orleans in 1854.

Originally, this parish was larger than it is today, running from Felicity Street in New Orleans to the St. Charles Parish line. However, as New Orleans grew, it absorbed the cities of Lafayette, Jefferson City, Carrollton, and several unincorporated areas (faubourgs). These became part of Orleans Parish. The present borders between Jefferson Parish and Orleans Parish were set in 1874. The Jefferson Parish seat was moved to Gretna at the same time.[4]

NOTE: The City of Lafayette in Jefferson Parish, as it was recorded in U.S. Census records until 1870, should not be confused with the present city of Lafayette, Louisiana, in Lafayette Parish.

1940 to 2000

From the 1940s to the 1970s, Jefferson's population swelled with an influx of middle-class white families from Orleans Parish. The parish's population doubled in size from 1940 to 1950 and again from 1950 to 1960 as the parents behind the post–World War II baby boom, profiting from rising living standards and dissatisfied with their old neighborhoods, chose relocation to new neighborhoods of detached single-family housing. By the 1960s, rising racial tensions in New Orleans complicated the impetus behind the migration, as many new arrivals sought not only more living space but also residence in a political jurisdiction independent from New Orleans proper.

The earliest postwar subdivisions were developed on the Eastbank of Jefferson Parish ("East Jefferson") along the pre-existing Jefferson Highway and Airline Highway routes, often relatively far-removed from the New Orleans city line, as land prices were lower further away from New Orleans and land assembly was easier. The completion of Veterans Highway in the late 1950s, following a route parallel to Airline but further north, stimulated more development. The arrival of I-10 in the early 1960s resulted in the demolition of some homes in the Old Metairie neighborhood, where development began in the 1920s, but resulted in even easier access to suburban East Jefferson.

In the portion of Jefferson Parish on the Westbank of the Mississippi River ("West Jefferson"), large-scale suburban development commenced with the completion, in 1958, of the Greater New Orleans Bridge crossing the Mississippi River at downtown New Orleans. Terrytown, within the city limits of Gretna, was the first large subdivision to be developed. Subsequent development has been extensive, taking place within Harvey, Marrero, Westwego and Avondale.

Similar to the development trajectory observed by other U.S. suburban areas, Jefferson began to enjoy a significant employment base by the 1970s and 1980s, shedding its earlier role as a simple bedroom community. In East Jefferson, the Causeway Boulevard corridor grew into a commercial office node, while the Elmwood neighborhood developed as a center for light manufacturing and distribution. By the mid-1990s, Jefferson Parish was exhibiting some of the symptoms presented by inner-ring suburbs throughout the United States. Median household income growth slowed, even trailing income growth rates in New Orleans proper, such that the inner city began to narrow the gap in median household income, a gap at its widest at the time of the 1980 Census. St. Tammany Parish and, to a lesser extent, St. Charles Parish began to attract migrants from New Orleans, and increasingly even from Jefferson Parish itself. These trends were catalyzed by Hurricane Katrina, which destroyed much of New Orleans' low-income housing and propelled further numbers of lower-income individuals into Jefferson Parish.

Despite these challenges, Jefferson Parish still contains the largest number of middle class residents in metropolitan New Orleans and acts as the retail hub for the entire metro area.

Hurricane Katrina (2005)

Even though Jefferson Parish was affected by Hurricane Katrina, it has rebounded more quickly than Orleans Parish, since the devastation was not as severe. The parish has a current population of 432,000, which is 15,000 fewer people than was recorded by the 2000 U.S. Census. New Orleans' Katrina-provoked population loss has resulted in Jefferson Parish becoming the second most populous parish behind East Baton Rouge Parish, center of the Baton Rouge metropolitan area.

With the landfall of Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005, Jefferson Parish took a hard hit. On the East Bank, widespread flooding occurred, especially in the eastern part of the parish, as well as much wind damage. Schools also were reported to have been severely damaged. On the West Bank, there was little to no flooding, though there was still much wind damage. As a result, the Jefferson Parish Council temporarily moved the parish government to Baton Rouge. Evacuees of Jefferson Parish were told that they could expect to be able to go back to their homes starting Monday, September 5, 2005 between the hours of 6 a.m. CDT and 6 p.m. CDT, but would have to return to their places of evacuation because life in the area was not sustainable. There were no open grocery stores or gas stations, and almost the entire parish had no electric, water, or sewerage services. Moreover, evacuations out of New Orleans were continuing to be staged from the heart of Metairie at the intersection of Interstate 10 and Causeway Boulevard, and traffic throughout the area was primarily restricted to emergency and utility vehicles.

Aaron Broussard, the parish president, issued the following statement, which was posted on the parish's website:

Jefferson Parish is not a safe place to return to at this time. Therefore, I am exercising my authority under the Louisiana Disaster Act and issuing a 'lock out' order for all Jefferson Parish citizens until 6 a.m. on Monday, September 5th.I have asked the Governor to utilize the State Police and National Guard for assistance in this mandatory lockout. This time will be needed to clear debris from streets so people can enter Jefferson Parish at their own risk.

We are at a catastrophic, disastrous impasse. There are a tremendous amount of trees down, gas leaks, low water pressure, and downed electrical lines which could start a fire that we have no way of putting out. There are no traffic controls. Many places are still flooded and this standing water will become toxic.

Jefferson Parish emergency managers will need this time to at least clear major East/West thoroughfares so that you can enter Jefferson Parish. However, I strongly suggest that you just come here to gather more belongings and leave, as it will still be a dangerous place. I cannot stress strongly enough that there will be no stores to purchase food or supplies so please do so prior to coming back to Jefferson Parish.

Try to stay with friends and relatives out of the hurricane affected area during the weeks to come. We cannot sustain any viable quality of life in Jefferson Parish at this time or for some time to come.

On September 3, as thousands of New Orleans residents were being evacuated into the parish, Parish President Aaron Broussard facetiously declared on local radio that Jefferson Parish would become a separate country to be called "Jeffertania" in hopes that this would get the attention of the Federal Government. "Please excuse my cynicism," Broussard said. "I just can't take this ineffectiveness anymore."[5]

On September 4, Jefferson Parish President Aaron Broussard broke down on Meet the Press[6]

RUSSERT: You just heard the director of Homeland Security’s explanation of what has happened this last week. What is your reaction?BROUSSARD: We have been abandoned by our own country. Hurricane Katrina will go down in history as one of the worst storms ever to hit an American coast. But the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina will go down as one of the worst abandonments of Americans on American soil ever in U.S. history. … Whoever is at the top of this totem pole, that totem pole needs to be chainsawed off and we’ve got to start with some new leadership. It’s not just Katrina that caused all these deaths in New Orleans here. Bureaucracy has committed murder here in the greater New Orleans area and bureaucracy has to stand trial before Congress now....

Three quick examples. We had Wal-Mart deliver three trucks of water. FEMA turned them back. They said we didn’t need them. This was a week ago. FEMA, we had 1,000 gallons of diesel fuel on a Coast Guard vessel docked in my parish. When we got there with our trucks, FEMA says don’t give you the fuel. Yesterday — yesterday — FEMA comes in and cuts all of our emergency communication lines. They cut them without notice. Our sheriff, Harry Lee, goes back in, he reconnects the line. He posts armed guards and said no one is getting near these lines…

I want to give you one last story and I’ll shut up and let you tell me whatever you want to tell me. The guy who runs this building I’m in, Emergency Management, he’s responsible for everything. His mother was trapped in St. Bernard nursing home and every day she called him and said, "Are you coming, son? Is somebody coming?" and he said, "Yeah, Mama, somebody's coming to get you." Somebody's coming to get you on Tuesday. Somebody's coming to get you on Wednesday. Somebody's coming to get you on Thursday. Somebody's coming to get you on Friday… and she drowned Friday night. She drowned Friday night! [Sobbing] Nobody's coming to get us. Nobody's coming to get us… (Video: WMV MOV)

By the following weekend, the local electrical utility, Entergy, had restored power to large swaths of Jefferson Parish, and the parish public works department had restored water and sewer service to most of the areas with power. East Jefferson General Hospital never ceased operation, even through the storm. Nevertheless, Mr. Broussard continued to discourage residents from returning until all major streets were clear of downed trees, powerlines and major debris. The parish's initial focus was on helping businesses through the "Jumpstart Jefferson" program that allowed business operators into the parish before residents. Nevertheless, some independent-minded residents began moving back into the parish even before Broussard issued a formal "all-clear", and some gas stations, grocery stores, restaurants and a Home Depot were in operation during this time.

Broussard's report of the events he discussed on Meet the Press have subsequently proven to be inaccurate. The son of the drowned woman was later identified as Thomas Rodrigue, who replied, "No, no, that's not true," when told of Broussard's account. An MSNBC interview with the man revealed that Rodrigue tried to contact his mother at the St. Rita nursing home on the days before the storm – Saturday, August 27 and Sunday, August 28, not Monday through Friday as Broussard had claimed—to encourage the home to evacuate. They did not, resulting in the deaths by drowning of more than 30 other residents.

Crucially, Jefferson's levees and floodwalls did not fail in the wake of Katrina, enabling floodwaters to be rapidly pumped out. As of October 2006, Jefferson Parish had, in effect, completely rebounded from Hurricane Katrina, while far more damaged Orleans Parish continued recovering at a slower rate. Estimates of Jefferson Parish's population ranged from 420,000 to 440,000, and this figure was expected to continue to rise as evacuated residents from Orleans Parish returned to metropolitan New Orleans. [7]

Katrina-related flooding

Flooding on the east bank has been frequently attributed to the decision by parish leadership to deactivate the stormwater pumping systems and evacuate the operators during the storm. Katrina's substantial storm surge may have swamped even operating pumping stations but Broussard's activation of the parish's "Doomsday Plan" is the most frequently cited reason for the flooding in all areas of the east bank except Old Metairie and parts of Harahan. Pump operators were evacuated to areas outside the parish that were themselves severely affected by the storm and pump station personnel were consequently unable to immediately return to restart the pumps. They did not arrive until the morning of August 31. Water resulting from the backflow through the non-operating pumping stations, as well as storm-related rainwater, remained on the streets and in the homes of residents of Metairie and Kenner for a day and a half. Many homes which were not severely damaged by storm winds took heavy flood damage, especially along both sides of the West Esplanade canal, from the 17th Street Canal to Kenner. The parish has subsequently announced that it will change the way it evacuates critical personnel during an emergency, both through the construction of "safe-houses" and use of existing facilities on the west bank of Jefferson Parish. The original "safe-house" project was severely modified due to rising costs and was further delayed due to a conflict of interest revealed by the original contractors. There are also plans to add manual closures on the pumping stations due to the failure of the compressed air systems during Katrina's storm surge.

Much additional consideration has been given to the different problem of the flooding in Old Metairie that resulted from Jefferson Parish's reliance on the failed Orleans Parish drainage system at the 17th Street Canal and its Pumping Station No. 6. Flooding in this area south of Metairie Road between the Orleans Parish line and Causeway Boulevard was catastrophic and deep water destroyed much of the most expensive real estate in the parish. A temporary plan was devised to pool water at the Pontiff Playground and south of Airline Drive and to divert some into other Jefferson Parish drainage canals. A longer-term project to divert water from this vulnerable area into the Mississippi River has also been suggested, although its expense appears to be prohibitive. Jefferson Parish officials have also struggled to maximize the parish's ability to utilize the significantly reduced pumping capacity of the 17th Street Canal if the threat of storm surge again requires the Corps of Engineers to close the mouth of the canal.

Gretna controversy

The city of Gretna, Louisiana, the parish seat of Jefferson Parish, made news after its police force participated, along with Crescent City Connection Police and Jefferson Parish Sheriff's deputies, in a road block on the Crescent City Connection Bridge in the days following Hurricane Katrina. The purpose was to stop evacuees from crossing over into the evacuated communities on the Westbank of the Mississippi River. Gretna Police had charge of Westbank-bound lanes, while Jefferson Parish deputies controlled the east bank-bound lanes and the bridge police closed the transit lanes.

Initially, as many as 6,000 evacuees were permitted to cross and were shuttled out of the area on buses; however, that operation was eventually discontinued as available fuel supplies were exhausted. Without transportation or sufficient supplies of food or water, west bank law enforcement personnel determined that they were unable to further assist the evacuees. It was also believed at that time that federal relief efforts and supplies were soon to be concentrated in the downtown area of New Orleans. The decision to stop further evacuees from crossing the river was then made after Oakwood Center was looted and burned by evacuees from the east bank of New Orleans. A unified local police decision was made to lock down all areas. Due to the lack of effective communications during the crisis, some New Orleans police officers independently continued to direct evacuees to buses across the bridge that were no longer operational. The inevitable confrontation occurred on the section of the bridge controlled by the Gretna police, and warning shots were fired over the heads of desperate evacuees who had been misdirected onto the bridge.

In the immediate aftermath of the storm, the Oakwood Center had been looted and set on fire.

Post–Katrina

A business report released in April 2007 found Jefferson Parish led the nation in job growth, for the quarter ending September 30, 2006, [8] as rebuilding continued after Hurricane Katrina. Jefferson Parish president Aaron Broussard believes that Jefferson Parish will reach pre-Katrina numbers or even exceed those numbers, as residents who are still evacuated from New Orleans return to Jefferson Parish to be closer to New Orleans as they await federal recovery money to repair their homes.[9]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the parish has a total area of 665 square miles (1,720 km2), of which 296 square miles (770 km2) is land and 370 square miles (960 km2) (56%) is water.[10]

Lake Pontchartrain is situated in the northern part of Jefferson Parish with the parish line several miles north of the southern shore, with St. Tammany Parish at its northern shore. The Mississippi River is located around the midpoint of Jefferson Parish flowing generally in a north-west to south-east direction.

Surrounding parishes include St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana at the north shore of Lake Ponchartrain, St. Charles Parish upriver to the west, Orleans Parish downriver to the east, and Plaquemines Parish downriver to the south-east. The majority of the southern half of Jefferson parish is uninhabited marshland with one of the exceptions being the town of Grand Isle; the only roads connecting Grand Isle to the rest of Jefferson Parish run through Lafourche Parish and St. Charles Parish.

National protected area

State parks

Adjacent parishes

- Orleans Parish (East)

- St. Bernard Parish (East)

- Plaquemines Parish (East)

- Lafourche Parish (West)

- St. Charles Parish (West)

- St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana (North)

Transportation

East Bank

Interstate 10 – connects the East Bank to St. Charles Parish upriver and New Orleans downriver.

Interstate 10 – connects the East Bank to St. Charles Parish upriver and New Orleans downriver. U.S. Highway 61 – connects the East Bank to St. Charles Parish upriver and New Orleans downriver.

U.S. Highway 61 – connects the East Bank to St. Charles Parish upriver and New Orleans downriver. U.S. Highway 90 – connects the East Bank to the West Bank on the south (via the Huey P. Long Bridge) and to New Orleans downriver (via Jefferson Highway).

U.S. Highway 90 – connects the East Bank to the West Bank on the south (via the Huey P. Long Bridge) and to New Orleans downriver (via Jefferson Highway).- Lake Pontchartrain Causeway – connects the East Bank to St. Tammany Parish on the north via Causeway Boulevard across Lake Pontchartrain.

West Bank

U.S. Highway 90 – connects the West Bank to the East Bank on the north (via the Huey P. Long Bridge) and to St. Charles Parish upriver .

U.S. Highway 90 – connects the West Bank to the East Bank on the north (via the Huey P. Long Bridge) and to St. Charles Parish upriver .

U.S. Highway 90 Business – connects the West Bank to New Orleans on the east and intersecting U.S. Highway 90 to the west. Planned future route of

U.S. Highway 90 Business – connects the West Bank to New Orleans on the east and intersecting U.S. Highway 90 to the west. Planned future route of  Interstate 49.

Interstate 49. Louisiana Highway 18 – connects the West Bank to St. Charles Parish.

Louisiana Highway 18 – connects the West Bank to St. Charles Parish. Louisiana Highway 23 – connects the West Bank to Plaquemines Parish.

Louisiana Highway 23 – connects the West Bank to Plaquemines Parish. Louisiana Highway 45 – connects the West Bank with the towns in the southern portion of Jefferson Parish (Jean Lafitte, Lafitte and Barataria)

Louisiana Highway 45 – connects the West Bank with the towns in the southern portion of Jefferson Parish (Jean Lafitte, Lafitte and Barataria)

Grand Isle

Louisiana Highway 1 – connects Grand Isle to Lafourche Parish

Louisiana Highway 1 – connects Grand Isle to Lafourche Parish

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1830 | 6,846 | — | |

| 1840 | 10,470 | 52.9% | |

| 1850 | 25,093 | 139.7% | |

| 1860 | 15,372 | −38.7% | |

| 1870 | 17,767 | 15.6% | |

| 1880 | 12,166 | −31.5% | |

| 1890 | 13,221 | 8.7% | |

| 1900 | 15,321 | 15.9% | |

| 1910 | 18,247 | 19.1% | |

| 1920 | 21,563 | 18.2% | |

| 1930 | 40,032 | 85.7% | |

| 1940 | 50,427 | 26.0% | |

| 1950 | 103,873 | 106.0% | |

| 1960 | 208,769 | 101.0% | |

| 1970 | 337,568 | 61.7% | |

| 1980 | 454,592 | 34.7% | |

| 1990 | 448,306 | −1.4% | |

| 2000 | 455,466 | 1.6% | |

| 2010 | 432,552 | −5.0% | |

| Est. 2015 | 436,275 | [11] | 0.9% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] 1790-1960[13] 1900-1990[14] 1990-2000[15] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the 2010 census, there were 432,552 people living in Jefferson Parish. The population density was 1,410 people per square mile (574/km²). There were 187,907 housing units at an average density of 613 per square mile (237/km²). The racial makeup of the parish was 60.82% White, 25.08% Black or African American, 0.68% Native American, 5.28% Asian, 0.13% Pacific Islander, 2.53% from other races, and 1.82% from two or more races. 14.85% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the 2000 census, there were 455,466 people living in Jefferson Parish. The population density was 1,486 people per square mile (574/km²). There were 187,907 housing units at an average density of 613 per square mile (237/km²). The racial makeup of the parish was 69.82% White, 22.86% Black or African American, 0.65% Native American, 3.09% Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, 2.18% from other races, and 1.65% from two or more races. 7.12% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 176,234 households out of which 31.90% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.20% were married couples living together, 15.40% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.80% were non-families. 26.70% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.40% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.56 and the average family size was 3.13.

In the parish the population was spread out with 25.30% under the age of 18, 9.10% from 18 to 24, 30.20% from 25 to 44, 23.40% from 45 to 64, and 11.90% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 92.40 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.60 males.

The median income for a household in the parish was $38,435, and the median income for a family was $45,834. Males had a median income of $35,081 versus $24,921 for females. The per capita income for the parish was $19,953. About 10.80% of families and 13.70% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.00% of those under age 18 and 9.80% of those age 65 or over.

Between the 2000 U.S. Census and the 2010 U.S. Census the population of Jefferson Parish decreased while the population of Hispanics increased. Greg Rigamer, a consultant of WWL-TV Eyewitness News, a chief executive officer of GCR and Associates, and a demographer stated. He argued that the population increased because Hispanics came after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to assist the already existing Hispanic community in Jefferson Parish before Katrina. As of 2011, more than 15% of the parish population is Hispanic.[16]

Government and infrastructure

Michael S. Yenni is the current President of Jefferson Parish, elected in 2015.

The Bridge City Center for Youth, a juvenile correctional facility for boys operated by the Louisiana Office of Juvenile Justice, is in Bridge City in an unincorporated area in the parish.[17]

Education

The parish's public schools are operated by Jefferson Parish Public Schools. Jefferson Parish Library operates the public libraries.

Economy

Largest employers

According to the Parish's 2011 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[18] the top employers in the parish are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ochsner Health System | 11,402 |

| 2 | Jefferson Parish Public Schools | 7,000 |

| 3 | Superior Energy Services | 4,400 |

| 4 | Huntington Ingalls Industries | 3,800 |

| 5 | Jefferson Parish | 3,671 |

| 6 | ACME Truck Line | 2,500 |

| 7 | East Jefferson General Hospital | 2,310 |

| 8 | Planet Beach | 2,000 |

| 9 | West Jefferson Medical Center | 1,849 |

| 10 | Jefferson Parish Sheriff's Office | 1,500 |

Other notable employers

Friedrich Custom Manufacturing, a leading maker of police barricades, including the ones used by the New York City Police Department.[19]

Politics

In the 2008 Presidential election, Jefferson Parish cast a majority of votes for Republican John McCain, who won 63% of the vote and 113,191 votes. Democrat Barack Obama won 36% of the votes and 65,096 votes. Although John McCain easily won Jefferson Parish, in the U.S Senate race that same year between Democrat Mary Landrieu and Republican John Neely Kennedy, Landrieu won Jefferson Parish. She won 52% of the vote and 91,966 votes. John Kennedy won 46% of the vote and 79,965 votes. Other candidates won 2% of the vote. In 2004, Republican George W. Bush won 62% of the vote and 117,882 votes. Democrat John F. Kerry won 38% of the votes and 72,136 votes.[20]

Communities

Cities

Towns

Census-designated places

Notable residents

- John Alario, Republican state senator from Jefferson Parish and Senate President since 2012; former Democratic Speaker of the Louisiana House of Representatives (1984–1988, 1992–1996)

- Sherman A. Bernard (1925–2012), Louisiana insurance commissioner from 1972 to 1988

- Jay Chevalier, singer and politician

- Robert Billiot, member of the Louisiana House of Representatives for Jefferson Parish since 2008;[21] former educator from Westwego, succeeded John Alario in the House

- Tom Capella, Republican assessor of Jefferson Parish; former state representative and former Jefferson Parish Council member

- Patrick Connick, Republican state representative from Jefferson Parish

- Charles Cusimano, former state representative and judge from Jefferson Parish

- Ellen Degeneres, American stand-up comedian, television host and actress born at Ochsner Hospital in Jefferson Parish in 1958

- Jim Donelon, Louisiana insurance commissioner; former state representative

- Eddie Doucet, state representative for District 78 in Jefferson Parish from 1972 to 1988

- David Duke, former state representative for District 81 in Jefferson Parish

- Robert T. Garrity, Jr., former state representative for District 78 in Jefferson Parish

- Randal Gaines, African-American member of the Louisiana House for St. Charles and St. John the Baptist parishes; former resident of Kenner

- James Garvey, Jr., Republican member of the Louisiana Board of Elementary and Secondary Education for District 1, which includes Jefferson Parish

- Kernan "Skip" Hand, former state representative and former Jefferson Parish district court judge

- Jennifer Sneed Heebe, former state representative and former member of the Jefferson Parish Council; resident of New Orleans since 2008[22]

- Girod Jackson, III, Democratic former state representative for District 87 in Jefferson Parish

- Hank Lauricella (1930–2014), college football All-American for the Tennessee Volunteers; state representative and state senator

- Harry Lee (1932–2007), iconic longtime sheriff of Jefferson Parish from 1980 to 2007

- Tony Ligi, Republican former state representative for District 79 in Jefferson Parish; director of the Jefferson Business Council

- Hall Lyons, oilman and politician, originally from Shreveport; son of longtime Louisiana oilman and politician Charlton Lyons

- Danny Martiny, state senator from Jefferson Parish

- Elwyn Nicholson, state senator from Jefferson Parish from 1972 to 1988

- Newell Normand, Jefferson Parish sheriff since Harry Lee's death in 2007

- Julie Quinn, Republican former state senator from Jefferson

- Steven Seagal, Reserve Chief Deputy of Jefferson Parish

- Julie Stokes, Republican current state representative from District 79

- James St. Raymond, Republican former state representative for District 89 in Orleans Parish; businessman, former resident of Jefferson Parish[23]

- Ricky Templet, Republican former state representative from Jefferson Parish; Gretna city council member

- Steve Theriot, former state representative and former state legislative auditor; accountant and lobbyist

- David C. Treen (1928–2009), former Congressman (1973–1980) and governor (1980–1984); later relocated to St. Tammany Parish

- John S. Treen, politician

- Chris Ullo, member of both houses of the state legislature (1972–2008)

- Roger F. Villere, Jr., chairman of the Louisiana Republican Party

- Ebony Woodruff, state representative for District 87 in Jefferson Parish since 2013

See also

References

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 168.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-01-14. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ "Worldandnation: New Orleans looks hard for first step". Sptimes.com. 2005-09-01. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ "ThinkProgress". ThinkProgress. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ "An emotional moment and a misunderstanding - US news - Katrina, The Long Road Back - Hurricanes Archive | NBC News". MSNBC.msn.com. 2005-09-27. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ "Jefferson Parish : JP Leads Nation in Job Growth" (posted), Jefferson Parish network, 2007, webpage: JParish-5688.

- ↑ "New Orleans population still cut by more than half". 29 November 2006 article by Reuters. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ "County Totals Dataset: Population, Population Change and Estimated Components of Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Hernandez, Monica. "Census shows growing Hispanic population in Jefferson Parish." (Archive) WWL-TV. February 4, 2011. Updated Saturday February 5, 2011. Retrieved on March 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Bridge City Center for Youth." Louisiana Office of Juvenile Justice. Retrieved on June 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Jefferson Parish, Louisiana Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- ↑ Frazier, Ian, "Streetscape: Do Not Cross," The New Yorker, June 2, 2014, p. 26.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-08-14. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- ↑ "Robert E. Billiot". Louisiana House of Representatives. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ↑ Richard Rainey (August 19, 2008). "Jennifer Sneed resigns Jefferson Parish Council". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ↑ "James St. Raymond". Intelius. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jefferson Parish, Louisiana. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Jefferson Parish. |

- Official website

- Jefferson Parish Sheriff's Office

- Jefferson Parish Convention and Visitors Bureau – Tourism

- Jefferson Parish Clerk of Court's Office

- Jefferson Historical Society of Louisiana

- East Jefferson Online Community – current events, history and organizational information.

|

Tangipahoa Parish | Lake Pontchartrain | St. Tammany Parish |  |

| St. Charles Parish | |

Orleans Parish and St. Bernard Parish | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Lafourche Parish | Gulf of Mexico | Plaquemines Parish |