Johann Nepomuk Maelzel

Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (or Mälzel; August 15, 1772 – July 21, 1838) was a German inventor, engineer, and showman, best known for manufacturing a metronome and several music automatons, and displaying a fraudulent chess machine.

Life and work

Maelzel was born in Regensburg. The son of an organ builder, he received a comprehensive musical education.[1] He moved to Vienna in 1792. After several years of study and experiment, he produced an orchestrion instrument, which was publicly exhibited, and afterward sold for 3,000 florins. In 1804, he invented the panharmonicon, an automaton able to play the musical instruments of a military band, powered by bellows and directed by revolving cylinders storing the notes.[1] This attracted universal attention; the inventor became noted throughout Europe, was appointed imperial court-mechanician at Vienna, and drew the admiration of Ludwig van Beethoven and other noted composers. This instrument was sold to a Parisian admirer for 120,000 francs.

In 1805 Maelzel purchased Wolfgang von Kempelen's half-forgotten automaton chess player, The Turk, took it to Paris, and sold it to Eugene Beauharnais at a large profit. Returning to Vienna, he gave his attention to the construction of an automaton trumpeter, which, with lifelike movements and sudden changes of attire, performed French and Austrian field signals and military airs. In 1808 he invented an improved ear trumpet, and a musical chronometer.

In 1813 Maelzel and Beethoven were on familiar terms. Maelzel conceived and musically sketched "The Battle of Vitoria" for which Beethoven composed the music; they also gave several concerts, at which Beethoven's symphonies were interspersed with the performances of Maelzel's automatons. In 1814, Beethoven wrote a deposition claiming that Maelzel had defrauded him, claiming ownership of this music, and illegally staging performances of it from an inaccurate transcription. Beethoven described Maelzel in this deposition as "a rude, churlish man, entirely devoid of education or cultivation".[2] In 1816 Maelzel became established in Paris as manufacturer of his newly invented metronome. Maelzel's metronome was copied from a metronome invented earlier by Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel.[1] By 1817, Beethoven and Maelzel appear to have patched things up. Beethoven wrote glowingly of Maelzel's metronome and declared he would stop using traditional tempo indications like allegro.[3]

In 1817 Maelzel left Paris for Munich, and then again took up his abode in Vienna. At this time he found means to repurchase von Kempelen's chess player, and, after spending several preparatory years in constructing and improving a number of interesting and effective mechanical inventions, he formed an enterprise devoted to exhibiting his array of mechanical wonders in the New World.

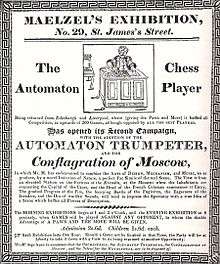

He arrived in New York City with his chess-player, trumpeter, panharmonicon, rope-dancers, miniature song-birds that sprang from the lids of snuff-boxes, speaking-dolls, and the "Conflagration of Moscow." The moving panorama of Moscow was wonderfully realistic and effective, with its music and cannonry. The smaller objects were genuine automatons, and marvels of beauty and ingenuity. Imitations of the "Conflagration" in after-years became adjuncts to most of the museums and shows in the large cities of the United States.

Often, when Maelzel's exhibition opened with the performance of the chess-player, he would call upon the audience in vain for an opponent, so little was the game in practice at that time. For many years Maelzel journeyed throughout the United States, repeating his exhibitions with unvarying success, and he also twice visited the West Indies.

It is said he had the faculty of seizing on the crude inspirations of others and perfecting them to his own advantage. He died on a ship in the harbor of La Guaira, Venezuela, reportedly from alcohol poisoning.[1]

Quotations

Views on Maelzel show that he was not always positively viewed by his contemporaries (e.g. regarding his relation to Art).

- Maelzel will be especially remembered [...] by the Metronome. [...]

As a man, Maelzel seems to have been quarrelsome, extravagant, and unscrupulous. [...] Had he possessed a larger amount of culture and of conscience, he might have done service to high Art.[4]

- — The Year-book of facts in science and art (1856)

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 German Wikipedia

- ↑ Beethoven’s Letters, Volume 1, Entry 127

- ↑ Beethoven’s Letters, Volume 1, Entry 211

- ↑ The Year-book of facts in science and art; 1856

References

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Maelzl, John Nepomuk". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Maelzl, John Nepomuk". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.