John C. Moss

John Calvin Moss (January 5, 1838—April 8, 1892) was an American inventor credited with developing the first practicable photo-engraving process in 1863. His work, and that of others such as William Leggo in Canada led to a revolution in printing and eventually to the mass marketing around the world of newspapers and magazines and books which combined photographs with traditional text.

Life

John Moss was born in Washington County, Pennsylvania, in 1838. At age 17 he became an apprentice to a Philadelphia printer. At 19, he married Mary A. Bryant who would become his partner in developing a workable photo-engraving method. Moss attributed much of his success to Mary’s help.

In 1858 Moss became a photographer and began experiments in photographic chemistry. Being both a practical photographer and a professional printer helped put him in the forefront of inventors who were striving to perfect a photo-engraving process.

At age 54, in 1892 he died at his home in Brooklyn, leaving behind his wife Mary and one son.[1]

Invention and career

Moss studied the work of Nicéphore Niepce (1765–1833), a French doctor who produced the world’s first photograph in 1826. He also mastered the technique of L.J.M Daguerre, a Frenchman who joined with Niepce to produce, in 1835, what became known as the first daguerreotype photograph, and which was followed by the worldwide commercial success of daguerreotypes.

A daguerreotype was made by exposing a polished silvered copper plate to an iodine vapor, which left a thin coat of light sensitive silver iodide on the copper. The plate was then placed over heated mercury, and the vapor combined with the silver particles to create an image. Sodium thiosulphate fixed the image.

The weakness in the process came from the fact that the finished photograph had to be framed behind sealed glass to prevent oxidation of the silver, which would cause the photograph to deteriorate. Each image was unique and no copy could be made. This was largely why the daguerreotype became obsolete within 20 years of its invention.

Another inventor, William Henry Fox Talbot, an Englishman, took the development a step further by inventing the world’s first multi-copy photographic process in 1841. He also used material sensitized with silver iodide. More progress was made by others, and in 1852 Fox Talbot patented a prototype of photo-engraving.

But finding a workable solution for the mass production of photographs and text printed on an ordinary printing press remained out of reach. This failure of technology became of particular interest as photography itself made great advances—illustrated by Mathew Brady’s work during the 1860s, in the American Civil War.

After another inventor tried but failed to etch a daguerreotype plate with electricity, Moss made a galvanic battery and began experiments that led in 1863 to the discovery of his photo-engraving process. It had taken him five years of relentless work.

This was Moss’ eureka! moment, although there were still problems to be resolved. Realizing the value of his invention, he and Mary moved in 1863 to New Jersey and then to New York City with dreams of making their fortune.

According to Benson J. Lossing “His wife stood by him with willing hands and an unswerving faith, while all his relatives tried to persuade him to abandon his hopeless and impoverishing quest.”[2]

It was Mary who persisted in repeating an experiment one night after Moss gave up and fell into bed with exhaustion. “Had not that experiment succeeded,” Moss wrote Lossing, “the Moss process might never had been heard of.”

In 1875, Scientific American described what happened to Moss and his wife for the next eight years: "There are some inventions which, though of great value, are slow in winning their way to public favor. This proved to be one of them. There existed in the minds of many publishers a strong prejudice against process engraving because several processes had been introduced, of which they had made trial with very unsatisfactory results. Time was required to prove that Moss’ process was not like the others.[3]

Perhaps an even greater obstacle arose from the opposition of wood engravers and the reluctance of artists to change their style of drawing to fit this new art. The wood engravers feared—quite rightly, as it turned out—that Moss’ invention would decimate their profession. The artists did not favor Moss because they were accustomed to sketching their drawings quickly with pencil and brush, leaving the finished work to be done by the slow and tedious toil of the wood engraver. Moss’ process required that they spend enough time to complete their drawings, which would then be photographed.

In the face of active opposition by wood engravers and the yawning indifference of publishers, Moss and his wife struggled in their home-workshop under penurious circumstances for eight years, attracting few clients, until they finally found several backers willing to invest in a new company devoted to photo-engraving.

Commercialization

Actinic Engraving Company

The Actinic Engraving Company was formed in 1871 in New York City. Michael George Duignan, who was one of Moss’ first backers, had published a massive work of a quarter million words in 1862, entitled Positive Facts without a Shadow of Doubt, which showed him to be an eccentric visionary with theories ranging from religion to philosophy to international affairs. One chapter of his book was—perhaps facetiously—titled “How to Torment Your Wife.”[4]

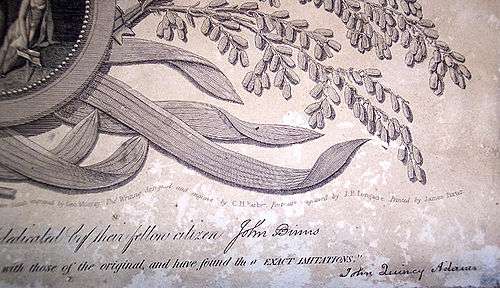

Duignan urged the Actinic Company to make its national debut by publishing the first photo-engraved copy of the American Declaration of Independence. Facsimiles of the Declaration of Independence had been popular from the 1820s until the 1850s and the outbreak of the Civil War. One in eight American families had a Declaration framed on the wall of their homes. The most famous facsimiles were produced by two competing entrepreneurs, John Binns and Benjamin Tyler.[5]

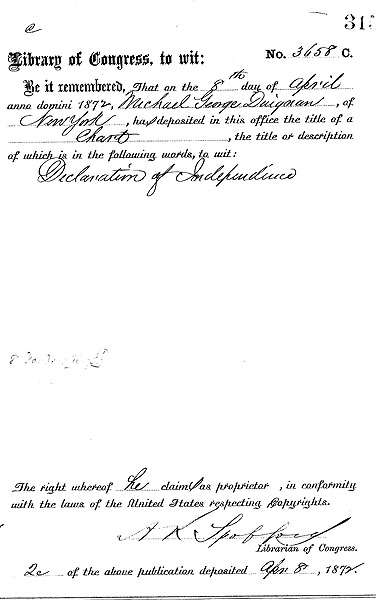

Duignan obtained the John Binns facsimile of an ornamental Declaration of Independence, published in 1819, and gave it to Moss to be photo-engraved. Duignan deleted John Binns' name from the original dedication which appears at the bottom of the document and inserted his own name. He also deleted Binns' notice of copyright: "Entered according to Act of Congress the 4th of November 1818 by John Binns of the State of Pennsylvania." Thus, Duignan falsely filed for a copyright in his own name and the copyright was granted.

In June 1872, two months later, Moss dissolved the Actinic Engraving Company and started over without Duignan. Moss later claimed rights to the improved photo-engraving process he developed in May 1872 but he made no mention of the facsimile of the Declaration of Independence he created during that period.

Moss Photo-Engraving Company

Moss found a more amenable investor and in 1873 founded the Moss Photo-Engraving Company. Scientific American and Puck and other periodicals gave him contracts that paved the way for success. He invented new machinery and techniques to speed up the process of photo-engraving.

By the early 1880s, according to Lossing, his 200 employees were annually turning out an amount of work that would have required at least 2,000 wood engravers. Moss photo-engraved original work, but a large part of his business consisted of reproducing woodcut and lithographic prints for mass production.

Thanks to Moss, America became the leader in the world for mass-producing periodicals and books that contained actual photographs instead of wood-engraved drawings.

Moss Engraving Company

Desiring to be, finally, the sole master of his own company and inventions, Moss left the Photo-Engraving Company in 1880 and established the Moss Engraving Company, which was also a success. He died twelve years later.

Rediscovery

Moss’ process was enhanced over the years by continuing innovations such as Frederick E. Ives’ invention in 1886 of half-tone engraving for newspaper photographs. His legacy appears today on everything from postcards to coffee table books. For 400 years before Moss’ invention, publications used wood engravings for illustrations, a labor-intensive process done by hand that did not lend itself to mass production.

Moss turned out to be an extraordinary inventor but a hard-luck businessman with not much talent for self-promotion. He received little recognition for his invention during his lifetime, except from colleagues in the printing and publishing industry.

Moss was rediscovered in 2009 by two art experts, Willis Van Devanter and Will Stapp[6][7] when they were asked to examine an unknown facsimile of the Declaration of Independence which Moss had created in 1872 with his new photo-engraving process. The document, which was found in a Paris antique shop, was thought to be possibly the only remaining copy in existence.

Then it is followed material taken from the Binns Declaration and concludes at the end with: “Engraved by Actinic Engraving Co, 113 Liberty Street, New York. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, by M.G. Duignan, in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. Printed by GEO Wheat & Co. 8 Spruce Street, New York.

References

- ↑ Obituary, The Publishers’ Weekly Vol. XLI January to June, 1892

- ↑ For a detailed personal account of John C. Moss and his wife Mary see The History of New York (1884) by Benson J. Lossing, pages 842-846.

- ↑ Scientific American 1845-1908; September 18, 1875; Vol. XXXIII; No. 12; pg. 178; Library of Congress, APS Online.

- ↑ Michael G. Duignan’s book Positive facts without a shadow of a doubt is in the Library of Congress. Positive facts without a shadow of a doubt, 2nd edition, New York, 1862

- ↑

- ↑ Willis Van Devanter

- ↑ Will Stapp